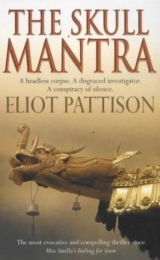

Текст книги "The Skull Mantra"

Автор книги: Eliot Pattison

Жанр:

Полицейские детективы

сообщить о нарушении

Текущая страница: 14 (всего у книги 26 страниц)

Chapter Ten

The two soldiers came for him as in a dream, seizing him as he slept in the dark, dragging him out of his bunk and putting on manacles. They did not speak as they shoved him into the car. They did not answer his questions, except to slap him viciously after the third one. Shan willed his body upright, fighting the pain, reminding himself what to look for. They were not Public Security, but infantry. Soldiers had more rules to follow. He was in a staff car, not a truck. They would not shoot him in a car. They were going out into the valley, not into the mountains where disposals were made. He leaned against the window, letting the glass hold the weight of his head, and watched where they were taking him.

It was the crossroads below the Dragon Claws, where Colonel Tan stood silhouetted against a dull gray sky. The two escorts dragged him toward Tan, released his wrists and moved back to the car, where they stood and lit cigarettes. One man muttered something. The other laughed.

"He said you would do this," Tan said. "Zhong said you would mock me. Try to use me."

"You'll have to be more specific," Shan muttered through a cloud of pain. "I only had three hours' sleep."

"Stirring up the separatists. Conspiring to breach public security. Leading soldiers into ambush."

Shan became aware of a dull rasping sound. Beyond Tan's car he saw a familiar gray truck. The rear hatch door was open, revealing the two booted feet of a sleeping figure.

"Is that what Sergeant Feng told you?" Shan's jaw felt numb. "That he was ambushed?" He touched his lip. His fingers came away smeared with blood.

"He had orders to call when he returned last night. Woke me up. Completely frantic. Asked for reinforcements. Says to give you to Public Security." Tan glanced to the north. A column of trucks was approaching.

"Perhaps he didn't tell you how he shot one of the tires," Shan said. "Or how he climbed onto the roof of the truck and wouldn't come down? Or that I had to drive back because he was too hysterical?"

The convoy overtook them. Shan recognized it at once, although there were twice as many trucks as usual. The extras were filled with knobs. He watched in despair. They would go to the South Claw. The knobs would set up their machine guns. The prisoners would walk up the slope and sit, working their makeshift rosaries, waiting.

As the dust of the column settled Shan saw that two of the trucks had stopped. A dozen bone-hard commandos leapt from one truck and formed two lines at the rear of the second. A Tibetan prisoner was thrown out of the shadows and landed between the lines, groaning in pain. Others began to climb out. Shan realized Tan was not looking at the prisoners, but at him.

The prisoners, fifteen in all, were marched twenty feet into the heather and ordered to form a line. Two knob officers appeared from behind the truck with submachine guns and took up positions on the road, facing the monks.

"No!" Shan moaned. "You can't-"

"I have the authority," Tan said with a chill. "Their strike is an act of treason."

Shan stumbled forward. It was just another of his nightmares, he told himself. He would wake up any moment in his bunk. He fell to his knee. A piece of gravel painfully pierced his skin. He was awake. "They did nothing," he groaned.

"You will stop your masquerade. I will have a prosecutor's report on the murderer Sungpo. In one week."

The prisoners began a mantra. They fixed their eyes over the heads of the executioners, staring toward the mountains.

Tan still did not move his gaze from Shan.

Shan's tongue seemed unable to move. He fought a rising nausea. "I will not help to kill an innocent man," he said in a cracking voice. He shook his head, hard, to clear the pain, and looked up at Tan with new strength. "If that is what you want, I request to join these prisoners."

Tan did not reply.

The officers cocked their weapons. Shan sprang forward. Someone grabbed him from behind and held him as they fired. The roar of the weapons echoed down the valley.

When the smoke cleared, three of the prisoners were on their knees, sobbing. The others were still staring into the distance, chanting their mantra.

The knobs had used blanks.

"You breached security at the South Claw!" Tan barked. "Who authorized you to enter a restricted zone?"

Shan met Tan's gaze now. "The murder scene is now off-limits to your murder investigator?"

"You said you were going to the monastery of Sungpo." Tan narrowed his eyes. "A prosecutor's report against the accused. Do you understand me?"

"Cruelty is never to be understood. It is to be endured." Shan closed his eyes. He felt something new rising. Anger. "Li Aidang would doubtless like my notes. I am going to tell one of these Public Security officers I need to speak to Li. Then I am going to climb into this truck"– he indicated the prisoners' vehicle-"and return to my work unit."

Tan lit one of his American cigarettes and moved silently around Feng's vehicle. He paused at the right rear, where the hubcap was missing and a mismatched tire was on the wheel. "Tell me about it," he growled as he returned to Shan.

Shan watched the prisoners being loaded as he spoke. "I was on the ridge, trying to understand what happened that night. Perhaps the hour was important, the hour he was killed. I wanted to know. There was a strange sound, like a large animal, then shots from the truck. I ran down. Sergeant Feng said there was a demon."

"Your demon Tamdin," Tan said tersely.

"He was hysterical. He said the demon was close, that he heard it speak. I was afraid for him. I asked for his gun."

Tan sneered. "And just like that, Sergeant Feng surrendered it to you."

"I returned it to him later, at the barracks."

"I don't believe you."

Shan fumbled in his pockets. "I kept the remaining bullets, to be safe." He dropped five cartridges into Tan's hand.

Tan stared at the bullets so long his cigarette burned to his fingers. He flinched and angrily threw the butt to the ground, then studied the dust of the convoy. "Everything's going to hell," he muttered, so low Shan was not certain he had heard correctly.

When he looked up there something new in his eyes, something Shan had not seen before. The barest glimpse of uncertainty. "It's all about the same thing, isn't it? The 404th strike and the trial of Sungpo. There's going to be a bloodbath and I am powerless to stop it."

Shan looked at him in surprise. "Do you want to stop it? Do you have the will to stop it?"

"What do you think I-" Tan began, but stopped as he looked down at the bullets. "Feng was scared. He and I served together for many years. He came to Lhadrung because I was here. I never saw him scared." Tan clenched his hand around the bullets and looked up. "Jao understood. In criticism sessions he used to say my only mistake was to think the old causes would have the same old effects in Tibet."

"Old causes have not done well here."

Tan gazed at the line of prisoners and sighed. "I am going to tell Zhong to allow them to be fed. To let the Buddhist charity in to feed them once a day."

Shan looked at him in disbelief, then slowly nodded. "It would be the right thing to do."

"Americans are coming," Tan said absently, then looked back at Shan. "You're bleeding."

Shan wiped the blood from his lip again. "It's nothing."

Tan extended a handkerchief.

Shan looked at it incredulously.

"I never told them to hit you."

Shan accepted it and held it to his lip, watching as Sergeant Feng appeared at the rear of the truck, stretching and yawning. Catching sight of Tan, Feng leaned back as if to hide, then straightened and solemnly marched to the colonel.

He looked awkwardly from Shan to Tan. "Request reassignment sir," he said, dropping his eyes to his boots.

"On what grounds?" Tan asked gruffly.

"On the grounds that I'm an old fool. I failed to remain vigilant in my duty. Sir."

"Comrade Shan," Tan said, "did Sergeant Feng lose vigilance at anytime last night?"

"No, Colonel," Shan observed. "His only fault perhaps was being too vigilant."

Tan began to return the bullets to Feng, then reconsidered and handed the bullets to Shan, who handed them to Feng. "Return to duty, Sergeant," Tan ordered.

Sergeant Feng accepted the bullets sheepishly. "Should've known," he muttered. "Can't shoot a demon." He saluted the colonel and wheeled about.

Tan looked again at the dust of the convoy. "There's too little time."

"Then help me. There's too much to do. I have to try to speak to Sungpo again. But I also have to find Jao's driver. Help me. He's the key to everything."

***

"Not a bowl touched. Not a kernel," the guard announced as Shan entered the cell block. There was a strange pride in his voice, as though his prisoner's starvation was a personal victory of some kind. "Nothing but tea."

Sungpo did not seem to have moved since Shan had seen him three days earlier. He sat erect and alert, wearing his thousand-mile stare.

"My assistant," Shan said, looking around the cellhouse. "I thought he would be here."

"He's with the other one."

"You have a new prisoner?"

The man shook his head. "Climbed the fence. Lucky bastard. Ten minutes earlier, ten minutes later, the perimeter patrol would have shot him down."

"An escapee?"

"No. That's the joke. He was trying to get in. Had to be taught that citizens may not freely enter military installations."

Shan found Yeshe in the building next door. He was wringing out a towel in a basin of blood-tinged water. Shan watched for a moment, noticing something different in Yeshe's face. He looked calmer somehow. It wasn't peace of mind he had found, but maybe a new deliberation.

Shan followed Yeshe into the interrogation room. At first he did not recognize the figure sitting on the table. One side of his face looked like a melon that had fallen off a speeding truck.

"Plenty hot good, eh?" the man said, raising one of his big pawlike hands in greeting. "He sent for me. I found him."

It was Jigme.

"What do you mean he sent for you?"

"You came, didn't you?"

"How could you be here so soon? You drove?"

His battered eyes somehow were able to twinkle. "I fly through the air. Like the old ones. The spell of the arrow."

"I've heard of it," Shan said. "I also remember seeing logging trucks on the road out of your valley."

Jigme tried to laugh but the sound emerged as a hoarse, hacking cough.

Shan and Yeshe pulled him to his feet and, one at each shoulder, half dragged, half carried him out of the building. They were stopped on the stairs by a furious officer.

"These prisoners belong to Public Security!" the officer roared.

"This man is part of my investigation," Shan said matter-of-factly and turned his back on the officer. Once inside the cell block, Jigme pulled himself away and straightened his clothing. He limped down the corridor alone and dropped to his knees with a cry of delight as he reached the last cell.

The guard at the cell door rose in protest. Shan cut him off with a gesture to open the cell.

Sungpo acknowledged Jigme with a nod which lit Jigme's bruised face. The gompa orphan closed the door behind him and surveyed the untouched bowls of rice. "Everything okay now," he said with a grateful smile to Shan.

"We need to speak with him."

Jigme seemed to think Shan had made an excellent joke. "Sure," he grinned. "Two years, one month, and eighteen days."

"He doesn't have that long."

Jigme soured and moved back to Sungpo with one of the bowls of rice. With small, affectionate strokes of his hand he began brushing the straw off Sungpo's robe.

"We have to speak with him," Shan repeated.

"You think he's scared to throw off a face?" Jigme shouted, suddenly defiant. "You people from the north, you're a fly on his shoulder." Shan saw a tear rolling down Jigme's cheek as he spoke. "He's a great man. A living Buddha. He'll die easy, no bother. He'll throw off a face and laugh at all of us in the next life."

***

They sat in an unused stall at the rear of the market and watched the sorcerer's shop. No one entered, no one exited. The market began to fill with vendors' carts piled high with spring greens, the early leaves of mustard and other plants that elsewhere on the planet would have been considered weeds.

Feng, still nervous from the night before, rubbed his palm over the handle of his pistol.

"I need fifty fen," Shan said.

"Who doesn't?" Feng cracked.

"For food. You have expense money."

"Not hungry."

"We had no breakfast. You did."

The announcement seemed to pain Feng, and Shan wondered if he was still stinging from the discovery of his nickname. Feng's eyes moved back and forth from Shan to Yeshe. "One of you stays here."

Yeshe, taking the cue, leaned back against the wall as though settling in.

Shan extended his hand and took the money.

Feng made a vague gesture toward the stalls in front of them. "Five minutes."

Shan lingered at a vendor selling writing supplies, then found a woman selling momos. He bought two for Yeshe, then moved to the first stall and quickly bought two sheets of rice paper, a writing brush, and a small ink stick.

"The first charm was requested a few days ago," a voice from behind suddenly declared.

Shan began to turn. An elbow pushed into his back. "Don't look," the man said.

Shan recognized the voice. It was the purba with the scarred face. He saw tattered felt boots behind him. The man was dressed as a herder.

"They're always looking for a chance," the purba said over Shan's shoulder. "Witches like Khorda, he'll take their money. They have steady money. Business is always good for their kind."

"I don't understand."

"This one, she works in a bookstore. Asked for the Tamdin charms about a week ago. Yesterday she asked for one against dogbite."

"She?"

"Daughter of a flesh monkey."

"A ragyapa?"

"Green Bamboo Street," came the reply.

Shan turned. The purba had disappeared.

***

Twenty minutes later Shan and Sergeant Feng watched from across the rutted gravel track on the north side of town as Yeshe ventured into the book shop. A short, swarthy woman could be seen inside as he entered. As he spoke to her she pointed toward the rear of the store, then looked up and down the street before pulling the door shut.

Yeshe darted out of the store ten minutes later, a glimmer of triumph on his face. "She's there," he announced. "That was her at the door. Says she's from Shigatse but she's not." He said that he had asked for the owner, explaining he was conducting a quick audit of working papers. When the man had begun to question his authority, Yeshe had pointed out the window. Seeing an official-looking vehicle and a soldier at the wheel, the man had quickly revealed his enterprise license and the girl's work papers. "Showed she was from Shigatse nearly a year ago. But on the way out I asked if she liked climbing the walls of the old fortress at Shigatse. She said she did, said she liked to take picnics there."

"There's a still a fortress there?" Shan asked.

"A fortress, in Tibet? Of course not, the Communists blew it up forty years ago!" He put his hands together as he spoke, then threw them apart, like an explosion. "No more walls."

"So she's not from Shigatse."

"Impossible. She lives in the back, but the owner say she leaves almost every weekend. A store clerk would never make enough to travel two hundred miles to Shigatse so often."

"Then her family is nearby," Shan said. A family of fleshcutters. In the mountains. Where Tamdin the fleshcutter lived. "That's where she is going with the charms." He looked expectantly at Yeshe.

Yeshe's face darkened. "No," he protested weakly.

"Her home shouldn't be hard to find," Shan suggested. "In Lhadrung there is an active market for death."

***

Tan handed him several sheets of paper clipped with a pin at the top. "I found her," he said, with the exhilaration that progress brings.

"Her?"

"Miss Lihua. Prosecutor Jao's secretary. On leave in Hong Kong. The Ministry of Justice tracked her to her hotel. She went to the local Ministry office and used the fax. Reports that Assistant Prosecutor Li drove her to the airport, before Jao left for dinner with the American woman. I know her. Young, very dedicated. Great memory for details. Gave me Jao's schedule. His calls on the day of his murder. She faxed it all. No one called about a meeting."

Miss Lihua was honored to be able to assist the colonel, the first fax said. She was stricken with grief over the loss of Comrade Prosecutor Jao and felt she should return immediately. Tan had declined the offer, provided she would cooperate by fax.

"Did she know how to find the driver?" Shan asked.

"Told me where he lived. And said she was certain no one Jao knew had set up a meeting at the South Claw."

"She wouldn't know," Shan said. "She wouldn't know if someone called."

"Jao was a stiff bastard. Never took calls himself. And everything had to be planned in advance or it could not happen. Every hour was logged by Miss Lihua. He was in the office all that day, she said. He was loading the car for the airport when she left. Religious Affairs called about a committee meeting. The Justice office in Lhasa called about a late report. He had her call to confirm his flights. Nothing else that day except the dinner."

"There are other places. Other ways to receive calls."

"This isn't Shanghai. He didn't have a damned pocket phone. He didn't have a radio transmitter. He didn't go anywhere that day anyway. And he wouldn't have changed his plans," Tan added, "wouldn't have chanced missing the flight for his annual leave just for a message from some monk."

"Exactly. Which is why it was someone he knew," Shan replied.

"No. It is why he must have been ambushed on the way to the airport, then driven back to the Claw."

"The road to the airport. It is a military road."

"Of course."

"So convoys drive down it into the valley. Do they travel at night?"

Tan nodded slowly. "When supplies or personnel are picked up at the airport. Flights arrive in the late afternoon."

"Then verify whether any military driver saw a limousine on his return drive. There aren't many limousines in Lhadrung. It would have been conspicuous."

Shan studied the folder with the faxes as he spoke. Madame Ko had added Prosecutor Jao's itinerary, obtained directly from the airline. "Why was he scheduled for a one-day layover in Beijing? Why not fly straight through?"

"Shopping. Family. Any number of reasons."

Shan sat down and stared into his hands. "I must go to Lhasa."

Tan's face soured. "There's no possible connection to Lhasa. If you think for a moment I'll drag in the outside authorities-"

"The prosecutor had planned an unaccounted-for day in Beijing. He received an unaccounted-for message from an unknown person who lured him to be killed by another unknown wearing an unaccounted-for costume."

"There's more than one killer?" Tan said, with a tone of warning in his voice.

Shan ignored the question. "We have to start answering questions, not raising more. In Lhasa," Shan explained, "there is the Museum of Cultural Antiquities. We need to account for all the costumes of Tamdin."

"Impossible. I can't protect you in Lhasa. It would be my head if you were discovered."

"Then you go. Check the museum records."

"Wen Li verified it. Said there are none missing. And I can't leave the district with the 404th on strike. It would be a sign of weakness." He looked up abruptly and cursed. "Listen to me. As if I'm apologizing. Nobody makes me-" The words choked in his throat.

There were few better lenses to the soul, Shan mused, than anger.

The colonel moved back to the window and picked up the binoculars.

Shan could see with his naked eye that the worksite was empty. "You are right, not to think of them as separate problems," he said very quietly.

Tan slowly lowered the glasses and turned to him.

"The murder and the strike," Shan said. "They are about the same thing."

"You mean the death of Jao."

"No. Not the death of Jao. The thing that caused the death of Jao."

As Tan stared at him the phone rang. He listened, uttered a single syllable of acknowledgment, and hung up. "Li Aidang," he announced with a frown, "is out collecting your evidence again."

***

Balti, the Ministry of Justice chauffeur, lived in a battered stucco and corrugated tin building that served as a government garage. Shan and the colonel followed voices up a steep stairway above the garage to a drafty, dim loft lined with shelves of auto parts. A long slab of plywood had been erected on cinder blocks to serve as a bed. On it were pieces of soiled canvas that appeared to have once served as drop cloths in the repair shop. On an upturned crate at the end of the bed was a butter lamp and a small ceramic Buddha, badly chipped.

Two men were at the end of the room, using hand lanterns to examine the shelves.

"We would not want the assistant prosecutor to surpass our own diligence," Tan said under his breath. Shan half expected him to push him toward the shelves.

One of the men in the shadows approached. It was Li. He was wearing rubber gloves and had a koujiao tied around his mouth. What was he afraid of? Buddhist contagion?

"Brilliant!" he said to Shan, lowering the mask. "I never thought of it until Colonel Tan asked about the prosecutor's car."

"Thought about what exactly?" asked Shan.

"The conspiracy. This khampa. He forced the prosecutor to the South Claw. Drove him there against his will. To be murdered by Sungpo. It explains how Sungpo traveled to the Claw and back. Why the car is missing. Why Balti is missing." Li kept searching as he spoke. He examined a cardboard box near the bed. It held neatly folded clothing. He dumped it onto the floor and picked up each piece with an extended finger as if it might be infested with vermin. He knelt and looked under the bed, producing two shoes which he carelessly tossed behind him.

Shan bent and ran his hand under the bedding. Hidden underneath was a wrinkled, faded photograph of three men, two women, and a dog standing before a herd of yaks. His hand closed around something sharp and metallic. It was a circular piece of chrome. He held it at arm's length in confusion.

Tan took it from him and studied it. "Jiefang," he announced. "Hood ornament." Battered Jiefang trucks, sent to Tibet after a lifetime of work elsewhere, were fixtures on the region's roads.

Li grabbed the ornament and snapped an order to the man behind him, who produced a small clear plastic bag. Li ceremoniously dropped the chrome piece into the bag and looked at Shan with a gloating expression.

"You should watch American movies," Li declared as he moved to the edge of the bed. "Very instructive. Integrity of the evidence is the key." Energized by the find, Li tore the bed clothing away. Finding nothing else, he overturned the plywood, then probed with his hand into the cavities of the cinder blocks. At the last one he looked up victoriously, producing a rosary of plastic beads.

"The limousine. It's obvious." Li dangled the beads in front of Shan. "He was given Prosecutor Jao's Red Flag limousine as his reward for abetting the murder." He dropped the beads into another bag.

Yeshe awkwardly moved to the shelves of auto parts and began to absently move the cartons. A tattered postcard fell on the floor as he did so, an image of the Dalai Lama taken decades earlier.

"Excellent!" Li exclaimed, snatching the photo and patting Yeshe on the back. "You are learning, Comrade."

Yeshe stared blankly at Li. "It is permitted to own such pictures now," he said, "as long as they are not displayed publicly." Not quite an argument, but still there was objection in Yeshe's voice, a tone which surprised Shan and perhaps surprised Yeshe even more.

Li seemed not to notice. He waved the photo like a flag. "No, but look how old it is. It was illegal when it was taken. This is how we build cases, Comrade." An assistant held out another plastic bag, into which Li dropped the postcard.

Shan moved to the window at the other end of the room and rubbed his fingers through its grime. Outside he could see their vehicles. Someone was smoking a cigarette with Sergeant Feng. He rubbed the glass clean. It was Lieutenant Chang. Reflexively, Shan stepped backward. Something brushed against his foot as he did so. It was one of the shoes. He picked it up and ran his finger around its edge. It was of cheap vinyl and covered with dust. It was new, probably never worn, but still covered with dust. He picked up the second shoe. It was not a match. Like the first it seemed unworn, and like the first it was for the left foot. Shan returned to the ruins of the bed and searched. There were no other shoes.

"And this was a man who had been cleared by Public Security." Li was holding up the little Buddha.

"A little man with a fat belly is not illegal," Tan observed icily.

Li gave Tan a condescending look. "Comrade Colonel. You have little experience with the criminal mind." He punctuated his comment with a satisfied smile, then extended his arm and dropped the Buddha into another bag held out by one of his assistants.

A small crowd had gathered outside the garage. They scurried like frightened animals when Tan appeared, vanishing down an alley. Only a child remained, a tiny figure of three or four wrapped in a black yak hair robe tied with twine. The child, whose sex was not obvious, stood looking at Tan with intense curiosity.

"I have to find Balti," Shan said to Tan. "If he has disappeared it is because of that night."

"You heard Li. He is probably in Sichuan by now."

"You saw his clothes upstairs. His entire wardrobe, in that box. He didn't pack it. He wasn't planning to leave. Besides, how far do you think the man who lived in that loft would get, without travel papers, in illegal possession of a government car?"

"So he sold the car." Tan took a step toward the child.

"That is only one of the possibilities. He could have been part of the crime. Or he could have been killed. Or he could have fled in terror and is in hiding."

The child looked at Tan and laughed.

"From fear of your demon," Tan said.

"Or fear of reprisal. From someone he recognized that night," Shan said.

Tan paused, considering Shan's suggestion. "Either way, he's gone. Nothing you can do."

"I can talk to the neighbors. My guess is he lived here a long time. He was part of the neighborhood."

"Neighborhood?" Tan looked around at the piles of empty oil barrels, heaps of scrap metal, and dilapidated sheds that surrounded the garage.

"People live here," Shan said.

"Fine. Let's interrogate them. I want to see my investigator at work."

Someone called from the alleyway. The child did not respond.

Tan extended his hand toward the child. Suddenly three men appeared, square-built herdsmen holding poles in front of them as if to do battle. Instantly Sergeant Feng and Tan's driver were at the colonel's side, their hands on their weapons.

A short, stout woman ran between the men, crying out in alarm. She grabbed the child and shouted at the men, who slowly retreated.

A hardness settled over Tan's countenance. He lit a cigarette in silence, studying the alleyway. "All right. You do it. I'll send patrols back to the foot of the South Claw. Let's eliminate the most likely explanation first. We'll search for his body. They already looked below the cliff face when they searched for the head. But the driver's body could be anywhere. In the Dragon Throat gorge, maybe."

As Tan sped off, Shan directed Sergeant Feng to move the truck into the shadow of the garage, then sat with Yeshe on rusty barrels in the repair yard.

"Did you tell Li I was coming here?" Shan asked Yeshe as the neighborhood slowly returned to life. "Someone did. Just like with Jao's house."

"I told you before, if they asked, how could I refuse the Ministry of Justice?"

"Did they ask?"

Yeshe did not reply.

"A marker was on the rock in Sungpo's cave where Jao's wallet was found. Someone planted it there so the arresting team would find it."

Yeshe's face clouded. "Why do you tell me this?"

"Because you have to decide what it is you want to be. Priests react to prison in many ways. Some will always be priests. Others will always be prisoners."

Yeshe turned with a bitter glare. "So you say I'm a nonbeliever if I answer questions from the Ministry of Justice."

"Not at all. I am saying that for those with doubts, their actions begin to define their beliefs. I'm saying accept that you will always be a prisoner of men like Warden Zhong or decide not to accept it."

Yeshe stood and threw a pebble against the wall, then took a step away from Shan.

An old woman appeared, cast them a spiteful glance, then opened a blanket at the edge of the street and began arranging the pile of matchboxes, chopsticks, and rolled candy which were her only wares. She pulled a worn photograph from inside her dress and held it to her forehead, then set it in front of her on the blanket. It was a photo of the Dalai Lama. Three boys began a game of tossing pebbles into a discarded tire. A window in the tenement across from the garage opened and a bamboo pole bearing laundry appeared, hanging like a stick of prayer flags over the street.

Shan watched for five minutes, then selected a roll of candy from the woman, asking Yeshe to pay for it. "I am sorry for the disturbance," he said to her. "The man who lived here is missing."

"Damned fool of a boy," she cackled.

"You know Balti?"

"Go for prayer, I told him. Remember who you are, I told him."

"Was he in need of prayer?" Shan asked.

"Tell him," she said, turning to Yeshe. "Tell him only the dead don't need prayer. Except my dead husband," she sighed. "He was an informer, my husband. Pray for him. He became a rodent. He comes at night and I feed him bits of grain. The old fool."

One of the herdsmen, still holding his staff, approached her and muttered under his breath.

"Be quiet, you!" the widow spat. "When you're so rich none of us need work, you can tell me who to speak to."

She produced five cigarettes wrapped in tissue paper and arranged them on her blanket, then studied Yeshe. "Are you the one?"

"The one?" Yeshe asked awkwardly.