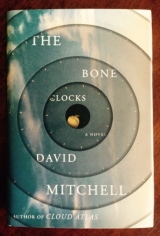

Текст книги "The Bone Clocks"

Автор книги: David Mitchell

Жанры:

Классическое фэнтези

,сообщить о нарушении

Текущая страница: 5 (всего у книги 40 страниц)

I’ve frozen. What’s he talking about? “Nothing, I swear, I just want to—to—to go away and—”

“Shut up. I’m thinking.” He takes a Granny Smith apple from a bowl on the sideboard, bites and chews. In the dull quiet, the sound of his munching is the loudest thing. “When did you last see Marinus?”

“My old doctor? At—at—at Gravesend General Hospital. Years ago, I—”

He holds up his hand for silence, like my voice hurts his ears. “And Xi Lo never told you that Jacko wasn’t Jacko?”

Till now the horror’s been high-pitched; with Jacko’s name, there’s a bass of dread. “What’s Jacko got to do with anything?”

He peers at his Granny Smith with disgust. “The sourest, blandest apples. People buy them for ornamental value.” He tosses it away. “There’s no Deep Stream field here, so we aren’t in a safe house. Where are we?”

I daren’t repeat my Jacko question, in case it brings this evil, ’cause evil’s the right word, to my brother. “Heidi’s gran’s bungalow. She’s in France, but she lets Heidi and …” They’re dead, I remember.

“The location, girl! County, town, village. Actlike you have a brain. If you’re the same Holly Sykes whom Marinus fouled, we must be in England, presumably.”

I don’t think he’s joking. “Kent. Near the Isle of Sheppey. I—I don’t think where we are actually has a … has a name.”

He drums the leather armchair. His fingernails are too long. “Esther Little. You know her?”

“Yes. Not really. Sort of.”

The drumming stops. “Do you want me to tell you what I’ll do to you if I think you’re lying, Holly Sykes?”

“Esther Little was by the river yesterday, but I never met her before. She gave me some tea. Green tea. Then she asked …”

The pale man’s stare drills into my forehead, like the answer’s written there. “ Whatdid she ask?”

“For asylum. If her …” I hunt for her exact words, “… plans went up in flames.”

The pale man lights up. “ So … Esther Little wanted you for an oubliette. A mobile safe house. I see. You! A used pawn so insignificant, she thought we’d forget you. Well.” He stands up and blocks the way out. “If you’re in there, Esther, we found you!”

“Look,” I manage to say, huddling, “if this is like MI5 stuff, about Ian and Heidi’s communism, I’m nothing to do with it. They just gave me a lift, and I … I …”

He steps towards me, suddenly, to scare me. It does. “Yes?”

“Don’t come near me.” My voice sort of shrivels up. “I’ll—I’ll—I’ll fight. The police—”

“Will be baffled by Heidi’s gran’s bungalow. Two lovers on the loungers, the body of teenager Holly Sykes. Forensics will have a proper farrago to disentangle by the time you’re found—especially if the triple murderer leaves the patio door ajar for the foxes, crows, stray cats … The mess! You’ll go national. The great, gory, unsolved British crime of the eighties. Fame at last.”

“Let me go! I—I—I’ll go abroad, I’ll … go. Please.”

“You’ll look adorable dead.” The pale man smiles at his fingers as he flexes them. “An unprincipled man would have some fun with you first, but I’m against cruelty to dumb animals.”

I hear a hoarse gasp. “Don’t don’t don’t please please—”

“Sssh …” His fingers make a twisting gesture and my lips, my tongue, and my throat shut down. All the strength drains from my legs and arms, like I’m a puppet with its strings cut, pushed into the corner. The pale man sits on the same rug I’m on, cross-legged, like a storyteller but sort of savoring the moment, like Vinny when he knows he’s going to have me. “What’s it like, knowing you’ll be dead as a fucking stone in sixty seconds, Holly Sykes? What pictures does your insectoid mind flick through just before the end?”

His eyes aren’t quite human. My vision’s going, like night’s falling, my lungs’re drowning, not in water but in nothing and I realize it’s been ages since I last breathed, so I try to but I can’t and the drumming in my ears has stopped ’cause my heart’s shut down. Out of the swarmy dusk the pale man reaches out his hand and brushes my breast with the backs of his fingers, tells me, “Sweet dreams, dear heart,” and my last thought is, Who is that doddering figure in the background, a mile away, at the far end of the lounge …?

The pale man notices, looks over his shoulder, and jumps up. My heart restarts and my lungs fill with oxygen, so quick I choke and cough as I recognize Heidi. “Heidi! Get the police! He’s a killer! Run!” But Heidi’s ill, or drugged, or injured, or drunk, her head’s lolling about like she’s got that disease, multiple sclerosis. Her voice isn’t the same, either—it’s like my granddad’s since his stroke. She pushes out the words all ragged: “Don’t worry, Holly.”

“On the contrary, Holly,” snorts the pale man, “if thisspecimen is your knight in shining armor, it’s time to despair. Marinus, I presume. I smell your unctuousness, even in that perfumed zombie.”

“Temporary accommodation,” says Heidi, whose head flops forward, back, then forward: “Why kill the two sunbathing youths? Why?That was gratuitous, Rhоmes.”

“Why not? You people, you’re so why why why? Because my blood was up. Because Xi Lo started a firefight in the Chapel. Because I could. Because you and Esther Little led me here. She died, didn’t she, before she could claim asylum in this female specimen of the great unwashed? A hell of a pounding she took, fleeing down the Way of Stones. I know, I gave it to her. Speaking of poundings, my sincere condolences over Xi Lo and poor Holokai—your little club of good fairies is de capitated. What about you, Marinus? You’re more a healer than a fighter, I know, but offer me some token resistance, I implore you.” Rhоmes does his finger-weaving thing and—unless I’m seeing things—the marble chopping board rises up from the counter in the kitchen and hovers towards us, like the invisible man’s bringing it over. “Cat got your tongue, Marinus?” asks the pale man called Rhоmes.

“Let the girl go,” says head-flopping Heidi.

The chopping board hurtles across the living room into the back of Heidi’s head. I hear a noise like a spoon going into an eggshell. It should’ve knocked Heidi’s body forward, like a skittle, but instead she’s picked up by—by—by—nobody, while Rhоmes spins his hands and makes sort of snapping motions, and Heidi’s body spins too, herkily-jerkily. Snap, crackle, pop, goes her spine, and her lower jawbone’s half off and blood’s trickling from a hole in her forehead, like a bullet went in. Rhоmes does a backhand slap in the air, and Heidi’s mangled body’s flung against a picture of a robin sat on a spade, then lands on its head and tumbles in a heap.

Now it’s like I’ve got headphones superglued over my ears and through one speaker I’ve got “None of This Is Happening” blaring and through the other “All of This Is Happening” going over and over at full blast. But when Rhоmes speaks, he speaks quietly and I hear every wrinkle in every word. “Don’t you ever have days when you’re just so glad to be alive you want to”—he turns to me—“howl at the sun? Now, I believe I was squeezing the life out of you …” He pushes the air towards me, palm-first, then lifts his hand; I’m slammed against the wall and shoved upwards by some invisible force till my head bumps the ceiling. Rhоmes leaps onto the arm of the sofa, like he’s going to kiss me. I try to hit him but both my hands are pinned back and once again my lungs’ve closed off. One of the whites of Rhоmes’s eyes is darkening to red, like a tiny vein’s burst: “Xi Lo inherited Jacko’s fraternal love for you, which pleases me. Killing you won’t bring my lost Anchorites back, but Horology owes us a blood debt now, and every penny counts. Just so you know.” My vision’s fading and the pain in my brain’s blotting everything out, and—

The tip of a sharp tongue slides from his mouth.

Reddened, metallic, an inch from my nose. A knife?

Rhоmes’s eyeballs roll back, and as his eyelids shut, I slip down to the floor, and he falls off the arm of the sofa. When the back of his head hits the floor, the knife blade is rammed out a couple more inches, flecky with white goo. It’s easily the most disgusting thing I’ve seen in my life and I can’t even scream.

“Lucky shot.” Ian drags himself in, gripping the counters.

It can only be me he’s talking to. There’s nobody left. Ian frowns at Heidi’s twisted body. “See you next time, Marinus. It’s time you got a newer vehicle, anyhow.”

What? Not “Oh, Holy Christ!” or “Heidi, no, Heidi, no, no!”? Ian looks at Rhоmes’s body. “On bad days you wonder, ‘Why not just back off from the war and lead a quiet metalife?’ Then you see a scene like this and remember why.” Last, Ian twists his busted head my way. “Sorry you had to witness all this.”

I slow my breathing, slower, and—“Who …” I can’t do more.

“You weren’t fussy about the tea. Remember?”

The old woman by the Thames. Esther Little? How could Ian know that? I’ve fallen through a floor and landed in a wrong place.

In the bungalow hallway a cuckoo clock goes off.

“Holly Sykes,” says Ian, or Esther Little, if it is Esther Little, but how’s that possible? “I claim asylum.”

Two dead people are lying here. Rhоmes’s blood’s soaking into the carpet.

“Holly, this body’s dying. I’ll redact what you’ve seen from your present perfect, for your own peace of mind, then I’ll hide deep, deep, deep in—” Now Ian-or-Esther-Little topples over like a pile of books. Only one eye’s open now, with half his face shoved up on the squashed sofa cushion. His eyes look like Davenport’s, the collie we had before Newky, when we had him put down at the vet’s. “Please.”

The word lifts a spell, suddenly, and I kneel by this Esther-Little-inside-Ian, if that’s what it is. “What can I do?”

The eyeball twitches behind its closing lid. “Asylum.”

I just wanted more green tea, but a promise is a promise. Plus, whatever just happened, I’m only alive ’cause Rhоmes is dead, and Rhоmes is only dead ’cause of Ian or Esther Little or whoever this is. I’m in debt. “Sure … Esther. What do I do?”

“Middle finger.” A thirsty ghost in a dead mouth. “Forehead.”

So I press my middle finger against Ian’s forehead. “Like this?”

Ian’s leg twitches a bit, and stops. “Lower.”

So I move my middle finger down an inch. “Here?”

The working half of Ian’s mouth twists. “There …”

THE SUN’S WARM on my neck and a salty breeze has picked up. Down in the narrow channel between Kent and the Isle of Sheppey a trawler’s blasting its honker: I can see the captain’s picking his nose, and looking for somewhere to put the bogie. The bridge is a Thomas the Tank Enginejob—the whole middle section rises up between two stumpy towers. When it reaches the top a klaxon sounds and the trawler chugs underneath. Jacko’d love this. I hunt in my duffel bag for my can of Tango and find a newspaper—the Socialist Worker. What’s this doing here? Did Ed Brubeck put it in for a joke? I’d chuck it over the barrier, but this cyclist bloke’s just arriving, so I open my Tango and watch the bridge. The cyclist’s ’bout Dad’s age, but he’s slim as a snake and nearly bald, where Dad’s a bit chubby, and it’s not for nothing his nickname’s Wolfman. “All right,” says the man, wiping his face on a folded cloth.

He doesn’t look like a pervert, so I answer him: “All right.”

The guy looks up at the bridge, a bit like he built it. “They don’t make bridges like that anymore.”

“Guess not.”

“The Kingsferry Bridge is one of only three vertical-lift bridges in the British Isles. The oldest is a dinky little Victorian affair over a canal in Huddersfield, just for foot traffic. This one here opened in 1960. There’s only two like it, for road and rail, in the world.” He drinks from his water bottle.

“Are you an engineer, then?”

“No, no, just an amateur rare-bridge spotter. My son used to be as mad about them, though. In fact”—he takes out a camera from his saddlebag—“would you mind taking a snap of me and the bridge?”

I say sure, and end up crouching to fit in both the man’s bald head and the bridge’s lifted-up section. “Three, two, one …” The camera whirrs, and he asks me to take another, so I do, and hand him back the camera. He thanks me and fiddles with his gear. I slurp my Tango and wonder why I’m not hungry, even though it’s almost noon and all I’ve eaten since I left Ed Brubeck asleep is a packet of Ritz crackers. I keep doing sausagey burps, too, which makes no sense. A white VW camper drives up and stops at the barrier. Two girls and their boyfriends are smoking and looking at me, all What does she thinkshe’s doing here?even though they’ve got an REO Speedwagon song on. To prove I’m not a no-friends sad-sack I turn back to the cyclist. “Come a long way, then?”

“Not far, today,” he says. “Over from Brighton.”

“Brighton? That’s like a hundred miles away.”

He checks a gizmo on his handlebars. “Seventy-one.”

“Is taking photos of bridges, like, a hobby of yours, then?”

The man thinks about this. “More a ritual than a hobby.” He sees I don’t understand. “Hobbies are for pleasure, but rituals keep you going. My son died, you see. I take the photos for him.”

“Oh, I …” I try not to look shocked. “Sorry.”

He shrugs and looks away. “It was five years ago.”

“Was it”—why don’t I just shut up?—“an accident?”

“Leukemia. He would have been about your age.”

The klaxon blasts again, and the road section’s lowering. “That must’ve been awful,” I say, hearing how lame it sounds. A long, skinny cloud sits over the humpbacked Isle of Sheppey, like a half-greyhound half-mermaid, and I’m not sure what else to say. The VW revs up and moves off the moment the barrier’s up, leaving a trail of soft rock in the air behind it. The cyclist gets on his bike. “Take care of yourself, young lady,” he tells me, “and don’t waste your life.”

He circles around and heads back to the A22.

All that way, and he never crossed the bridge.

CARS AND TRUCKS wallop by, gusting seeds off dandelion clocks, but there’s no one to ask the way to Black Elm Farm. Lacy flowers sway on long stalks as trucks shudder by, and blue butterflies are shaken loose. The tigery orange ones cling tighter. Ed Brubeck’ll be working at the garden center now, dreaming of Italian girls as he lugs bales of peat into customers’ cars. Must think I’m a right moody cow. Or perhaps not. The fact Vinny dumped me is fast becoming exactly that, a fact. Yesterday it was a sawn-off shotgun wound but today it’s more like a monster bruise from an air-rifle pellet. Yes, I trusted Vinny and I loved him, but that doesn’t make me stupid. For the Vinny Costellos of the world, love is bullshit they murmur into your ear to get sex. For girls—me, anyway—sex is what you do on page one to get to the love that’s later on in the book. “I’m well rid of that lechy bastard,” I tell a cow watching me over a gate, and though I don’t feel it yet, I reckon one day I will. Maybe Stella’s done me a favor, in a way, by tearing off Vinny’s nice-guy mask after only five weeks. Vinny’ll get bored of her, sure as eggs is eggs, and when she finds him in bed with another girl it’ll be herdreams of motorbike rides with Vinny that’ll get minced, just like mine were. Then she’ll come crawling back, eyes as red and sore as mine were yesterday, and ask me to forgive her. And I might. Or I might not. Up ahead there’s a roundabout and a cafй.

And the cafй’s open. Things are looking up.

THE CAFЙ’S CALLED Smoky Joe’s Cafй and it’s trying hard to be an American diner off Happy Dayswith tall booths you can’t see into, but it’s a bit of a shit-hole, really. There’s not many customers, most of them glued to the footy on the knackered telly up on the wall. A woman sits by the door, reading the News of the Worldin a cloud of cigarette smoke coming from her pinched nostrils. Buttony eyes, stitched lips, frizzy hair, a face full of old regrets. Over her head is a faded poster of a brown goldfish bowl with two eyes peering out and a caption saying: JEFF’S GOLDFISH HAD DIARRHEA AGAIN. She sizes me up and waves her hand towards the booths, meaning, Sit where you want. “Actually,” I say, “I just wanted to ask if you know how to get to Black Elm Farm.”

She looks up, shrugs, looks back, and breathes smoke.

“It’s here, on Sheppey. I’ve got a job there.”

She returns to her paper and taps her fag.

I decide to phone Mr. Harty: “Is there a pay phone?”

The old moo shakes her head, without looking up.

“Would it be possible just to make a local call using your—”

She glares at me, like I’ve asked her if she sells drugs.

“Well … might anyone else here know Black Elm Farm?” I hold her gaze for long enough to tell her the quickest way to get back to her paper is to help me.

“Peggy!” she bawls, into the kitchen. “Black Elm Farm?”

A clattery voice answers: “Gabriel Harty’s place. Why?”

Her button eyes swivel my way. “Someone’s askin’ …”

Peggy appears: she has a red nose, gerbil cheeks, and a smile like a Nazi interrogator’s. “Off fruit-picking for a few days, is it, pet? It was hops in my day, but hops is all done by machines nowadays. You take the Leysdown road—thataway”—she points left out of the door—“past Eastchurch, then take Old Ferry Lane on the right. On foot, are you, pet?” I nod. “Five or six mile, it is, but that’s a stroll in the park for—”

There’s a godalmighty clatter of tin trays from the kitchen and Peggy hurries back. I deserve a packet of Rothmans now I’ve got what I came in for, so I go to the machine in the main part of the cafй: Ј1.40 for a packet of twenty. Total rip-off, but there’ll be a bunch of new people at the farm so I’ll need a confidence booster. In go the coins before I can argue myself out of it, round goes the knob, plop go the ciggies. Only when I straighten, box of twenty Rothmans in hand, do I see who’s sat behind the machine, bang across the aisle: Stella Yearwood and Vinny Costello.

I duck down, out of sight, wanting to puke. Did they see me just now? No. Stella would’ve said something breezy and poisonous. There’s a gap between the machine and the screen. Stella’s feeding Vinny ice cream across the table. Vinny looks back like a lovesick puppy. She runs the spoon over his lips, leaving dribbly vanilla lipstick. He licks it off. “Give me the strawberry.”

“I didn’t hear the magic word,” says Stella.

Vinny smiles. “Give me the strawberry, please.”

Stella spikes the strawberry from the ice-cream dish and pushes it up Vinny’s nostril. He grabs her wrist with his hand, his beautiful hand, and guides the fruit into his mouth, and they look at each other, and jealousy burns my gut like a glass of neat Domestos. What sicko anti-guardian angel brought them to Smoky Joe’s right here, right now? Look at the helmets. Vinny’s brought Stella here on his precious untouchable Norton. She hooks her little finger through his, and pulls, so his arm and body follow, until he’s leaning all the way over the table and kissing her. His eyes are shut and hers aren’t. Vinny only mouths the next three words, but he never said them to me. He says it again, eyes wide open, and she looks like a girl unwrapping an expensive present she knew she was getting.

I could erupt and hurl plates, call them every name under the sun, and get a ride back to Gravesend in gales of tears and a police car, but I blunder back to the heavy door, which I pull instead of push and push instead of pull ’cause my vision’s melting away, watched by the old moo, oh, Christ, yeah, ’cause I’m bags more interesting than the News of the Worldnow, and those button eyes of her don’t miss one single detail …

OUT IN THE open air my face dissolves into tears and snot, and a Morris Maxi slows down for the old fart at the wheel to get a good eyeful and I shout, “What are youbloody looking at?” and, God, it hurts it hurts it hurts, and I clamber over this gate into a wheatfield, where I’m hidden from the roundabout, and now I sob and sob and sob and sob and sob and sob and punch the ground and punch the ground and sob and sob and sob … And That’s it, I think, I’ve no more tears left now, and then Vinny murmurs, “I love you,” and reflected in his beautiful brown eyes is Stella Yearwood and here we go again. It’s like puking up an iffy Scotch egg—every time I think I’m done, there’s more. When I calm down enough for a cigarette, I realize I dropped them by the machine in Smoky Joe’s. Bloody great. I’d rather eat cat shit on toast than everset foot inside that place. Then, of course, I recognize the growl of Vinny’s Norton. I creep to the gate. There they are, sat on the back, smoking—I just fucking bet—my fags, the fags I just paid Ј1.40 for. Stella would’ve spotted the box at the foot of the machine, still in its cellophane, and picked it up. First she steals my boyfriend, now it’s my fags. Then she climbs onto the Norton, puts her arms round Vinny’s waist, and buries her face in his leather jacket. Away they go, down the road to the Kingsferry Bridge, into the streaky blue yonder, leaving me grimy and hidden like a tramp with crows in a tree going What a laaarf … What a laaarf …

The wind strokes and stirs the wheat.

The wheat ears go pitter patter pitter.

I’ll never get over Vinny. Never. I know it.

TWO HOURS AFTER the roundabout I get to an end-of-the-world village called Eastchurch. There’s a sign saying ROCHESTER 23. Twenty-three miles? Little wonder I’ve got blisters like Ayers Rock on my feet. Strange thing is, after the Texaco garage in Rochester it’s all a bit of a blur till the Kingsferry Bridge onto Sheppey. Actually, it’s a total blur. Like a section of a song that’s been taped over. Was I walking along in a trance? Eastchurch is in a trance. There’s one small Spar supermarket, but it’s shut ’cause it’s Sunday and the newsagent next to it’s shut, too, but the owner’s moving about inside so I knock till he opens up and get a packet of Digestive biscuits and a jar of peanut butter, plus another pack of Rothmans and a box of matches. He asks if I’m sixteen so I look him straight in the eye and say I turned seventeen in March, actually, which does the trick. Outside I light up as a mod and his modette drive by on a scooter, staring at me, but my mind’s on the shrinking pounds and pence I’ve got left. I’ll get more money tomorrow, as long as Mr. Harty doesn’t play funny buggers, but I don’t know how long this working holiday of mine’s likely to last. If Vinny and Stella were out when Mam or Dad went to find me at Vinny’s house, they won’t know I’m not with him, so they won’t know I’ve left Gravesend.

There’s a phone box by the bus stop. Mam’d go all sarky and Mammish if I phone her, but if I phone Brendan’s hopefully Ruth’ll answer, and I’ll say to get the message to Dad—not Mam, Dad—that I’m okay but I’ve left school and I’ll be away for a bit. Then Mam won’t be able to send me on a you-could’ve-been-abducted guilt trip the next time we meet. But when I open up the phone box I find the receiver’s been ripped off its cord, so that’s that.

Perhaps I’ll ask to phone from the farm. Perhaps.

· · ·

IT’S NEARLY FOUR P.M. by the time I turn down Old Ferry Lane onto the chalky track that leads to Black Elm Farm. On-and-off sprinklers in the fields spray cool clouds, and I sort of drink the vapor in like super-fine water-floss, and look at the little rainbows. The farmhouse itself is an old, hunkered-down brick building with a modern bit stuck on the side, and there’s a big steel barn, a couple of buildings made from concrete blocks, and a windbreak of those tall thin trees. Here comes this black dog, like a fat seal on stumpy legs, barking its head off and wagging its whole body, and in five seconds flat we’re best mates. Suddenly I miss Newky, and I pet the dog’s head.

“I see you’ve met Sheba.” A girl in dungarees steps out of the older part of the house; she must be about eighteen. “You’ve just arrived for picking?” Her accent’s funny—Welsh, I think.

“Yeah. Yes. Where do I … check in?”

She finds my “check in” amusing, which pisses me off ’cause how am I s’posed to know the right word? She jerks her thumb at the door—she’s wearing wristbands over both wrists like some tennis star but they just look spaz to me—and walks over to the brick barn to tell all the other pickers ’bout the new girl who reckons she’s staying at a hotel.

“THERE’LL BE TWENTY pallets’ worth by three o’clock tomorrow, see,” comes a man’s voice from the office down the hall, “and if your truck isn’t here at one minute past three, then the lot’ll be going to the Fine Fare depot in Aylesford.” He hangs up and adds, “Lying twat.” By now I’ve recognized Mr. Harty from my phone call this morning. The door behind me flies open and an older woman in stained overalls, green wellies, and a spotted neckerchief thing sort of shoos me on. “Chop suey, young lady, the doctor will see you now. Mush-mush. New picker, yes? Of course you are.” She bustles me forwards into a poky office smelling of potatoes in a sack. There’s a desk, a typewriter, a phone, filing cabinets, a poster with GLORIOUS RHODESIA on it and photos of wildlife, and a view of a farmyard and a decomposing tractor. Gabriel Harty’s in his sixties, has a low-tide sort of face and hair tufting out of his nose and ears. Ignoring me, he tells the woman, “Bill Dean was just on the blower. Wanted to discuss ‘a distribution niggle.’ ”

“Let me guess,” says the woman. “His drivers have all got bubonic plague, so could we run tomorrow’s strawberries over to Canterbury.”

“Ye-es. Know what else he said? ‘I wish you landowners would try to help the rest of us.’ Landowner. The bank owns the land and the land owns you. That’s what being a landowner means. He’s the one taking his family to the Seychelles, or wherever it is.” Mr. Harty relights his pipe and stares out of the window. “Who are you?”

I follow his gaze to the dead tractor until I realize he means me. “I’m the new picker.”

“New picker, is it? Not sure if we need any more.”

“We spoke on the phone this morning, Mr. Harty.”

“A long time ago, this morning. Ancient history.”

“But …” If I don’t have a job here, what’ll I do?

The woman looks over from the filing cabinet: “Gabriel.”

“But we’ve already got this—this Holly Benson-Hedges girl on her way. She rang up this morning.”

“That’s me,” I tell him, “but it’s Holly Rothmans and …” Hang on, is he being funny? He’s got one of those faces where you can’t tell. “That’s me.”

“That was you, was it?” Mr. Harty’s pipe makes a death-rattle noise. “That’s lucky, that is. Then we’ll see you tomorrow at six, sharp. Not two minutes past six. No. Nobody sleeps in, we’re not a holiday camp. Now. I have more telephone calls to make.”

“THE PLACE IS rather deserted on Sundays,” says Mrs. Harty, as we walk back across the farmyard. She’s posher than her husband and I wonder what their story is. “Most of our Kentish pickers go home on Sundays for a few creature comforts, and the student mob have decamped to the beach at Leysdown. They’ll be back by evening, unless they get waylaid at the Shurland Arms. So: The shower’s over there, the loo’s down there, and there’s the laundry room. Where did you say you’ve come from today?”

“Oh, just …” Sheba dashes up and runs happy rings round us, which gives me longer to get my story straight “… Southend. I just took my O levels last month. My parents are busy working and I want to save a bit of money, and a friend of a friend worked here a couple of summers ago, so my dad said okay, now I’m sixteen, so …”

“So here you are. Is it sayonara to school?”

Sheba follows a scent trail behind a pile of tires.

“Will you be going back to do A levels, Holly?”

“Oh, right. Depends on my results, I s’pose.”

Satisfied, and not that interested, Mrs. Harty leads me into the brick barn through the wide-open wooden door. “Here’s where most of the lads sleep.” Twenty or so metal beds are arranged in two rows, like in a hospital but with barn walls, a stone floor, and no windows. What I think of sleeping among a bunch of snoring, farting, wanking guys must show on my face, ’cause Mrs. Harty says, “Don’t worry—we knocked some partitions up this spring,” she points to the end, “to give the ladies some privacy.” The last third of the barn’s walled off to a height of two men or so with a plywood partition thing. It’s got a doorway with an old sheet across it. Someone’s chalked THE HAREM above the doorway, which someone’s drawn an arrow from to the words SIZE DOESMATTER GARY SO DREAM ON. Through the sheet, it’s a bit darker, and like a changing room in a clothes shop, with three partitions on either side, each with its own doorway, two beds, plus a bare electric bulb dangling from the rafters. If Dad was here he’d wince and mutter about health and safety regs, but it’s warm and dry and safe enough. Plus there’s another door in the barn wall with an inside bolt, so if there was a fire you could get out in time. Only thing is, all the beds look taken with a sleeping bag, a backpack, and stuff, until we get to the last cubicle, the only one with the light on. Mrs. Harty knocks on the door frame and says, “Knock-knock, Gwyn.”

A voice inside answers, “Mrs. Harty?”

“I’ve brought you a roommate.”

Inside, the Welsh dungaree-wearing smirker is sitting cross-legged on her bed, writing in a diary or something. Steam’s rising from a flask on the floor, and smoke from a cigarette balanced on a bottle. Gwyn looks at me and gestures at the bed, like, It’s all yours. “Welcome to my humble abode. Which is now our humble abode.”

“Well, I’ll leave you two girls to it,” says Mrs. Harty, and goes, and Gwyn gets back to her diary. Well, that’s bloody nice, that is. F’Chrissakes, she could tryto make a bit of small talk. Scratty scrat-scratgoes her Biro. Probably writing ’bout me right now, and probably in Welsh, so I can’t read it. Well, if she’s not talking to me, I’m not talking to her. I dump my duffel bag on the bed, ignoring a Stella Yearwood–sounding voice saying that Holly Sykes’s great bid for freedom has ended in a total shit-hole. I lie next to my duffel bag ’cause I’ve got nowhere else to go and no energy. My feet feel well and truly Black & Deckered. I don’t have a sleeping bag, either.

MY GOALIE WHACKS the ball clean down the table and, slam!, straight into Gary the student’s goal and the impressed onlookers cheer. Brendan calls that shot my Peter Shilton Special, and used to whinge ’bout my left-handed goalie’s unfair advantage. Five-nil to me, my fifth victory in a row, and we’re playing winner stays on. “She bloody demolished me, what can I say?” says Gary, his face fiery and speech slurred after a few Heinekens. “Holly, you’re a progeny, no, a progidy, thassit, a prodigy, a bona fide bar-football prodigy—and there’s no dishonor in losing to … one of them.” Gary does a pantomime bow and reaches over the table with his can of Heineken so that I have to clink mine against his. “How d’you get to be so good?” asks this girl who’s easy to remember ’cause she’s Debby from Derby. I just shrug and say I always used to play at my cousin’s. But I remember Brendan saying, “I cannot believe I’ve been beaten by a girl,” which I’ve only just realized he said to make my victory sweeter.