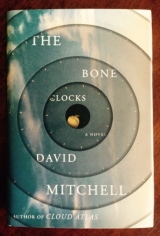

Текст книги "The Bone Clocks"

Автор книги: David Mitchell

Жанры:

Классическое фэнтези

,сообщить о нарушении

Текущая страница: 17 (всего у книги 40 страниц)

“Sorry I’ve never come over with Holly and Aoife. It’s just …”

“Work, I know. Work. Ye’ve wars to cover. I read your reportage when I can, though. Holly sends me clippings from Spyglass. Tell me, was your father a journalist as well? Is it in the blood?”

“Not really. Dad was a … sort of businessman.”

“Is that a fact now? What was his line, I wonder?”

I may as well tell her. “Burglary. Though he diversified into forgery and assault. He died of a heart attack in a prison gym.”

“Well, aren’t Ithe nosy old crone? Forgive me, Ed.”

“Nothing to forgive.” Some little kids rush by our table. “Mum kept me on the straight and narrow, down in Gravesend. Money was tight, but my uncle Norm helped out when he could, and … yeah, Mum was great. She’s not with us anymore either.” I feel a bit sheepish. “God, this is sounding like Oliver Twist. Mum got to hold Aoife in her arms, at least. I’m happy about that. I’ve even got a photo of them.” From the band’s end of the room comes cheering and clapping. “Wow, look at Dave and Kath go.” Holly’s parents are dancing to “La Bamba” with more style than I could muster.

“Sharon was telling me they’re after taking lessons.”

I’m ashamed to admit I didn’t know. “Holly mentioned it.”

“I know ye’re busy, Ed, but even if it’s just a few days, come over to Sheep’s Head this summer. My hens’ll find room for ye in their coop, I dare say. Aoife had a gas time last year. Ye can take her pony trekking in Durrus, and go for a picnic out to the lighthouse at the far tip of the headland.”

I’d love to say yes to Eilнsh, but if I say yes to Olive, I’ll be in Iraq all summer. “If I possibly can, I will. Holly has a painting she did of your cottage. It’s what she’d rescue if her house was on fire. Our house.”

Eilнsh puckers her pruneish old lips. “D’ye know, I remember the day she painted it? Kath came over to see Donal’s gang in Cork, and parked Holly with me for a few days. 1985, this was. They’d had a terrible time of it, of course, what with … y’know. Jacko.”

I nod and drink, letting the icy gin numb my gums.

“It’s hard for them all at family occasions. A fine ball of a man Jacko’d be by now, too. Did ye know him at all, in Gravesend?”

“No. Only by reputation. People said he was a freak, or a genius, or a … Well, y’know. Kids. I was in Holly’s class at school, but by the time I got to know Holly well, he was … It’d already happened.” All those days, mountains, wars, deadlines, beers, air miles, books, films, Pot Noodle, and deaths between now and then … but I still remember sovividly cycling across the Isle of Sheppey to Gabriel Harty’s farm. I remember asking Holly, “Is Jacko here?” and knowing from her face that he wasn’t. “How well did you know Jacko, Eilнsh?”

The old woman’s sigh trails off. “Kath brought him over when he’d’ve been five or so. A pleasant small boy, but not one who struck you as so remarkable. Then I met him again, eighteen months later, after the meningitis.” She drinks her Drambuie and sucks in her lips. “In the old days, they’d’ve called him a ‘changeling,’ but modern psychiatry knows better. Jacko at six was … a different child.”

“Different in what way?”

“He knewthings—about the world, about people, all sorts … Things small boys just don’t—can’t—shouldn’t know. Not that he was a show-off. Jacko knew enough to hide being a dandy, but,” Eilнsh looks away, “if he grew to trust ye, ye’d be given a glimpse. I was working as a librarian in Bantry at the time, and I’d borrowed The Magic Faraway Treeby Enid Blyton for him the day before he arrived because Kath’d told me he was a fierce reader, like Sharon. Jacko read it in a single sitting, but didn’t say if he’d enjoyed it or not. So I asked him, and Jacko said, ‘My honest opinion, Auntie?’ I said, ‘I’d not want a dishonest one, would I?’ Jacko said, ‘Okay, then I found it just a little puerile, Aunt.’ Six years old, and he’d use a word like ‘puerile’! The following day, I took Jacko to work with me and—not a word of a lie—he pulled Waiting for Godotoff the shelves. By Beckett. Truth be told, I assumed Jacko was just attention-seeking, wanting to amaze the grown-ups. But then at lunchtime we ate our sandwiches by the boats, and I asked him what he’d made of Samuel Beckett, and”—Eilнsh sips her Drambuie—“suddenly Spinoza and Kant were joining our picnic. I tried to pin him down and asked him straight, ‘Jacko, how can you know all this?’ and he replied, ‘I must have heard it on a bus somewhere, Auntie—I’m only six years old.’ ” Eilнsh sloshes her glass. “Kath and Dave saw consultants, but as Jacko wasn’t ill, as such, why would they care?”

“Holly’s always said that the meningitis somehow rewired his brain in a way that … massively increased its capacity.”

“Aye, well, they do say that neurology’s the final frontier.”

“You don’t buy the meningitis theory, though, do you?”

Eilнsh hesitates: “It wasn’t Jacko’s brain that changed, Ed, it was his soul.”

I keep a sober face. “But if his soul was different, was he still—”

“No. He wasn’t Jacko anymore. Not the one who’d come to visit me when he was five. Jacko aged seven was someone else altogether.” Octogenarian faces are hard to read; the skin’s so crinkled and the eyes so birdlike that facial clues are obscured. The band have been nobbled by the Corkonian contingent; they strike up “The Irish Rover.”

“I presume you’ve kept this view to yourself, Eilнsh?”

“Aye. They’d be hurtful words as well as mad-sounding ones. I only ever put it to one person. That was himself. A few nights after the Beckett day there was a storm, and the morning after Jacko and I were gathering seaweed from the cove below my garden, and I came right out with it: ‘Jacko, who are ye?’ And he answered, ‘I’m a well-intentioned visitor, Eilнsh.’ I couldn’t quite bring myself to ask, ‘Where’s Jacko?’ but he must’ve heard the thought, somehow. He told me that Jacko couldn’t stay, but that he was keeping Jacko’s memories safe. That was the strangest moment of my life, and I’ve known a few.”

I flex my leg; it’s gone to sleep. “What did you do next?”

Eilнsh face-shrugs. “We spread the seaweed over the carrot patch. As if we’d agreed a pact, if you will. Kath, Sharon, and Holly left the next day. Only,” she frowns, “when I heard the news that he’d gone …” she looks at me, “… I’ve always wondered if the way he left us wasn’t related to the way he first came …”

An uncorked bottle goes pop!and a table cheers.

“I’m honored you’re telling me all this, Eilнsh, honestly—but why are you telling me all this?”

“I’m being told to.”

“Who … who by?”

“By the Script.”

“What script?”

“I’ve a gift, Ed.” The old Irishwoman has speckled woodpecker-green eyes. “Like Holly’s. Ye know what it is I’m talking of, so ye do.”

Chatter swells and falls like the sea on shingle. “I’m guessing you mean the voices Holly heard when she was a girl, and the, well, what in some circles would be called her moments of ‘precognition.’ ”

“Aye, there’s different names for it, right enough.”

“There are also sound medical explanations, Eilнsh.”

“I’m quite sure there are, if ye set store in them. The cluas faoi r ъ n, we’d call it in Irish. The secret ear.”

Great-aunt Eilнsh has a bracelet of tiger’s-eye stones. Her fingers fret at it while she’s talking and watching me.

“Eilнsh, I have to say—I mean, I respect Holly very much, and y’know … she’s definitely highly intuitive—bizarrely, sometimes. And I’m not rubbishing any traditions here, but …”

“But ye’d as soon eat your arm off as buy into this mumbo-jumbo about second sight and secret ears and whatever else this mad old West Cork witch is banging on about.”

That’s exactly what I think. I smile an apology.

“And that’s all well and good, Ed. For ye …”

I notice a headache knocking at my temples.

“… but not for Holly. She has to live with it. It’s hard—I know. Harder for Holly in shiny modern London, I’d say, than for me in misty old Ireland. She’ll need your help. Soon, I think.”

This is probably the weirdest conversation I’ve ever had at a wedding. But at least it’s not about Iraq. “What do I do?”

“Believe her, even if you don’t believe in it.”

Kath and Ruth walk up, glowing from their Latin dance action. “You two have been sat here thick as thieves for ages.”

“Eilнsh has been telling me about her Arabian adventures,” I say, still wondering about the old woman’s last line.

Ruth asks, “ Didyou see Kath and Dave dancing?”

“We did and fair play to ye both,” says Great-aunt Eilнsh. “That’s a mighty set of tail feathers Dave’s sprouted—at his time of life, too.”

“We’d go dancing when we first met,” says Kath, who sounds more Irish in the midst of the tribe, “but it stopped when we took on the Captain Marlow. No nights off together for thirty-odd years.”

“It’s almost three o’clock, Eilнsh,” says Ruth. “Your taxi’ll be here soon. You might want to start your goodbyes.”

No! She can’t go all paranormal on me and just leave. “I thought you’d be around for tonight, at least, Eнlish.”

“Oh, I know my limits.” She stands up with the aid of her stick. “Oisнn’s chaperoning me to the airport, and my neighbor Mr. O’Daly’ll meet me at Cork airport. Ye have your invitation to Sheep’s Head, Ed. Use it before it expires. Or before I do.”

I tell her, “You look pretty indestructible to me.”

“We all of us have less time than we think, Ed.”

CLOUDS CURDLED PINK in the narrow sky above the blast barriers lining the highway into Baghdad from the southwest. Traffic was chocka and slow, even on the side lanes, and for the last mile to the Safir Hotel the Corolla was moving at the speed of an obese jogger. Overladen motorbikes lurched past. Nasser was driving, Aziz was snoozing, and I slumped low behind my screen of hanging shirts. Baghdad’s a dark city now in all senses—there’s no power for the streetlights—and dusk brings a Transylvanian urgency to get home and bar the door behind you. We’d seen some ugly things and Nasser was in a bleaker-than-usual mood. “My wife, okay, Ed, she had good childhood. Her father worked at oil company, she go to good school, money enough, she smart, she study, Baghdad a good place then. Even after Iranian war begin, many American companies here. Reagan send money, weapons, CIA helpers for Saddam—chemicals for battle. Saddam was America ally, you know this. Good days. I a teenager then, too, Suzuki 125, leather jacket, very cool. Talk in cafйs with friends, all night. Girls, music, books, this stuff. We have future then. My wife’s father have connections, so I don’t join army. Thank the God. I got job in radio station, I work at Ministry of Information. War is over. At last, we think, Saddam spend money on country, on university, we become like Turkey. Then Kuwait happen. America says, ‘Okay, invade, Kuwait is local border dispute.’ But then—no. UN resolution. We all think, What the fuck? Saddam like cornered animal, cannot retreat with face. In Kuwait war my job was verrrycreative—to paint defeat like victory for Saddam. But future was dark, then. At home, we listen to BBC Arab Service at home, in secret, my wife and me. So, so, so jealous of BBC journalists, who is free to report real news. That Iwanted to do. But, no. We wrote lies about Kurds, lies about Saddam and sons, lies about Ba’ath Party, lies about how Iraq future is bright. If you try write truth, you die in Abu Ghraib. Then 9/11, then Bush say, ‘We take down Saddam.’ We happy. We scared, but we happy. Then, then, Saddam, that son of bitch, he gone. I thought, God is Great, Iraq begin again, Iraq rises like … that firebird, how you say, Ed?”

“Phoenix.”

“So I think, Iraq rise like phoenix, I become realjournalist. I think, I go where I want, I speak who I want, I write what I want. I think, My daughters will have careers, like my wife had career once, their future good now. Saddam statue pulled down by Iraqi and Americans—but by night looting begin from museum. U.S. soldiers, they just watch. General Garner said, ‘Is natural, after Saddam.’ I think, My God, America has no plan. I think, Here come Dark Ages. Is true. My daughters’ school hit by missile, in war. Money for new school was stolen. So no school, for months and months now. My daughters not go out. Is too danger. All day they argue, read, draw, dream, wash if there is water, watch neighbor TV if there is power. They see teenage girls in America, in Beverly Hills, go to college, drive, date boys. TV girls, they have bedrooms bigger our apartment, and rooms just for clothes and shoes. My God! For my girls, dream is like torture. When America go, in Iraq, only two future. One future is place of guns, knives, Sunni fight Shi’a, it never end. Like Lebanon in 1980s. Other future is place of Islamists, Shariah, burkas. Like Afghanistan now. My cousin Omar, last year he escape to Beirut, then he go in Brussels to find girl to marry, any girl, old, young, any who have EU passport. I say, ‘Omar, in name of God, you fucking crazy! You not marry a girl, you marry passport.’ He say, ‘For six years I treat girl nice, treat her parents nice, then plan careful, divorce, I EU citizen, I free, I stay.’ He there now. He succeed. Today I think, No, Omar not crazy. We who stay, we crazy. Future is dead.”

I didn’t know what to say. The car edged past a crowded Internet cafй, full of slack-jawed boys holding game consoles and gazing at screens where American marines shot Arab-looking guerrillas in ruined streetscapes that could easily be Baghdad or Fallujah. The game menu had no option to be a guerrilla, I guess.

Nasser fed his cigarette butt out of the window. “Iraq. Broken.”

I’M POSSIBLY A bit drunk. Holly’s over by the silver punch bowls, among an asteroid belt of women talking nineteen to the dozen. Webbers, Sykeses, Corkonian Corcorans, A. N. Others … Who the hell areall these people? I pass a table where Dave’s playing Connect 4 with Aoife and losing with theatrical dismay. I never play with Aoife like that; she giggles as her granddad clutches his head and groans, “ Nooooo, you can’thave won again! I’m the Connect 4 king!” Wishing I’d responded to Holly’s frostiness earlier less frostily, I decide to offer Holly an olive branch. If she uses it to hit me across the face, then we’ll clearly establish who’s the moody cow and who occupies the moral high ground. I’m only three tight clusters of poshly attired people away from the woman officially known as my partner—when I’m intercepted and blocked by Pauline Webber, wielding a gangly young man. The lad’s dressed for a teenage snooker tournament—purple silk shirt, matching waistcoat, pallid complexion. “Ed, Ed, Ed!” she crows. “Reunited at last. This is Seymour, who I told you allabout. Seymour, Ed Brubeck, real liferoving reporter.” Seymour flashes a mouthful of dental braces. His handshake’s a bony grab, like a UFO catcher’s. Pauline smiles like a gratified matchmaker. “Do you know, I’d stab someone in the heart with a corkscrew for a camera right nowjust to capture the two of you?” Though she does nothing about commandeering one.

Seymour’s handshake is exceeding the recommended limit. His brow is constellated with angry zits—see the squashed W of Cassiopeia—and the drunken feeling that I’ve already dreamt this very scene is superseded by the feeling that, no, I only dreamt the feeling that I’ve dreamt this very scene. “I’m a big fan of your work, Mr. Brubeck.”

“Oh.” A wannabe newshound, seduced by tales of derring-do and sex with Danish photojournalists in countries suffixed withstan.

“You said you’d share a few secrets,” says Pauline Webber.

Did I? “Which secrets did I say I’d share, Pauline?”

“You devil, Ed.” She biffs my carnation. “Don’t play hard to get with me—we’re as good as family now.”

I need to get to Holly. “Seymour, what do you need to know?”

Seymour fixes me with his ventriloquist’s creepy eyes and wiry smile, while Pauline Webber’s voice slashes through the din: “What makes a great journalist a great journalist?”

I need painkillers, natural light, and air. “To quote an early mentor,” I tell the kid, “ ‘A journalist needs ratlike cunning, a plausible manner, and a little literary ability.’ Will that do?”

“What about the greats?” fires Pauline Webber’s voice.

“The greats? Well, they all share that quality Napoleon most admired in his generals: luck. Be in Kabul when it falls. Be in Manhattan on 9/11. Be in Paris the night Diana’s driver makes his fatal misjudgement.” I flinch as the windows blast in, but, no, that’s not now, that’s ten days ago. “A journalist marriesthe news, Seymour. She’s capricious, cruel, and jealous. She demands you follow her to wherever on Earth life is cheapest, where she’ll stay a day or two, then jet off. You, your safety, your family are nothing,” I say it like I’m blowing a smoke ring, “ nothing, to her. Fondly you tell yourself you’ll evolve a modus operandi that lets you be a good journalist anda good man, but no. That’s bollocks. She’ll habituate you to sights only doctors and soldiers should ever be habituated to, but while doctors earn sainthoods and soldiers get memorials, you, Seymour, will earn lice, frostbite, diarrhea, malaria, nights in cells. You’ll be spat on as a parasite and have your expenses questioned. If you want a happy life, Seymour, be something else. Anyway, we’re all going extinct.” Spent, I push past them and get to the punch bowls at bloody last …

… and find no sign of Holly. My phone vibrates. It’s from Olive Sun. I scroll through the message:

hi ed, hope wedding good, dufresne ok to interview thurs 22. can u fly cairns wed 21? dole fruits aunty take u direct from hotel. respond soonest, best, os

My first thought is, Result!Having excellent grounds for assuming that Spyglass’s communications are being intercepted by several government agencies, Olive Sun texts in code: Dufresne is our nom de textetaken from The Shawshank Redemptionfor the Palestinian tunneler-in-chief under the Gaza-Egyptian border; “Cairns” is Cairo; “dole fruits” is Hezbollah; and an aunty is a handler. It’s exactly the sort of Bondesque stuff that kids like Seymour suppose we do routinely, but there’s nothing remotely glamorous about being detained by the Egyptian security forces for seventy-two hours in a downtown Cairo bunker, waiting for a bored interrogator to come and ask you why you’re there.

I pitched the story to Olive last autumn and she’s pulled God knows how many strings to set this up. Dufresne, if he’s one man and not ten, has a mythical status in Egypt, the Gaza Strip, and Jordan. An interview would be a major coup and enhance our magazine’s reputation in Arab-speaking countries by a factor of ten. Blockades and sanctions have no news legs; there’s little to say and nothing to see. Who cares if Israelis ban imports of powdered milk into Gaza? Stories about tunnels under walls, however, that’s different. That’s Escape from Colditzstuff, that’s The Count of Monte Cristo, and people eat that shit with a spoon. I’m about to reply with a yes when I remember one catch: At seven P.M. next Wednesday, Miss Aoife Brubeck is appearing for one night only as the Cowardly Lion in St. Jude’s C of E Primary School’s performance of The Wizard of Oz, and her daddy is expected.

What kind of self-centered bastard would miss his own daughter’s star turn? Why care about other people’s six-year-olds who’ll never perform anything because they died when Israeli bulldozers or Hezbollah rockets destroyed their homes? They’re not ourkids. We’re clever enough to be born where such things don’t happen.

See the problem, Seymour?

THE SECURITY GUYS on duty at the Safir Hotel checkpoint recognized Nasser’s car, raised the barrier, and waved us through. Crunching to a halt, Nasser told me, “Okay, Ed, so Aziz and me, we come at ten tomorrow morning. You, me, we transcribe tapes. Aziz bring photographs. Amazing story. Olive is very happy.”

“See you at ten.” Still in the car, I handed Nasser an envelope of Spyglassdollars for the day’s fee. We all shook hands, Aziz let me out of his side, and the Corolla pulled away. It stopped after only a few yards. I thought it was mechanical trouble, but Nasser wound down his window and waved something at me. “Ed, take this.”

I walked over and he put his little tape recorder into my hand. “Why? You’re coming tomorrow.”

Nasser made a face. “If here with you, is safer. Many good words on the tape.” With that he drove around the roundabout and back to the checkpoint. I walked up the hotel steps. Every window was a dark rectangle. Even if the electricity is working, guests are warned to keep lamps off at night because of the risk of snipers. Meeting me in the metal-plated porch was Tariq, a security guard with a Dragunov. “How they hanging, Mr. Ed?” Tariq likes to practice his slang.

“Can’t complain, Tariq. Quiet day?”

“Today quiet. Thanks to God.”

“Is Big Mac back home already?”

“Yes, yes. The dude is in the bar.”

I tip Tariq and his three colleagues generously to tell me if outsiders are asking questions about me, and to be vague with their replies. Not that I can ever be sure Tariq isn’t pocketing fees from both sides, but the principle of the Golden Goose has held so far. From the porch I passed through the glass doors to the circular reception area, where a low-wattage lamp gleamed on the concierge’s desk. A mighty chandelier hangs overhead, but I’ve never seen it illuminated, and now it’s mightily cobwebbed. I never looked at it without imagining it crashing down. Mr. Khufaji, the manager, was helping a lad load used car batteries onto a luggage trolley. Dead batteries are exchanged for live ones every morning, like milk bottles when I was a kid. Guests use them to power laptops and sat-phones.

“Good evening, Mr. Brubeck,” said the manager, dabbing his forehead with a handkerchief. “You’ll be needing your key.”

“Good evening, Mr. Khufaji.” I waited while he fetched it from the drawer. “Could I have one of those batteries, please?”

“Certainly. I’ll send the boy up when he returns.”

“Most kind.” We retain old-school manners, even if Baghdad has gone to hell and the Safir was less a five-star hotel and more of a serviced campsite inside a dead hotel.

“I thought I heard your dulcet tones.” Honduran cigar in hand, Big Mac appeared from the dingy bar that served as common room, rumor mill, and favor exchange. “What time do you call this?”

“Later than you, which means you’re buying the beers.”

“No no no, the deal was the lastone back buys the beers.”

“That’s a shameless lie, Mr. MacKenzie, and you know it.”

“Hey. Shameless lies precipitate wars and make work for hungry hacks. Get any street action in Fallujah?”

“The cordon’s too tight. What about you day-trippers?”

“Waste of time.” Big Mac filled his lungs with cigar smoke. “Got to Camp Victory to be told the fighting had intensified, meaning the Marine Corps were too busy to keep our fat asses alive. We munched bullshit with press officers before being squeezed into a supply convoy heading back to Baghdad. Not the one that got IEDed into flying mince, obviously. You?”

“Better. We found a makeshift clinic for refugees from Fallujah, plus a shot-down Kiowa. Aziz took a few shots before a uniformed countryman of yours kindly suggested we leave.”

“Not bad, but”—Big Mac crossed the floor and lowered his voice, even though Mr. Khufaji had exited—“one of Vincent Agrippa’s ‘well-placed sources’ texted him twenty minutes ago about a ‘unilateral cease-fire’ coming into play tomorrow.”

I doubted that. “Mac, the Fallujah militia won’t roll over now. Perhaps as a regrouping exercise—”

“No, not the insurgents. The marines are standing down.”

“Bloody hell. Where is this source? General Sanchez’s office?”

“Nope. The army’ll be spitting cold shit over this. They’ll be, ‘If you’re going to take Vienna, take fucking Vienna.’ ”

“Do you think Bremer cooked this one up?”

“My friend: The Great Envoy couldn’t cook his own testes in a Jacuzzi of lava.”

“You’ll have to give me a clue, then, won’t you?”

“Since you’re buying the beers, here’s three.” Big Mac took a five-second cigar break. “C, I, and A. It’s a direct order from Dick Cheney’s office.”

“Vincent Agrippa has a source in the CIA? But he’s French! He’s a cheese-eating surrender monkey.”

“Vincent Agrippa has a source in God’s panic room, and it pans out. Cheney’s afraid that Fallujah’ll split the Coalition of the Willing—not that they’re a coalition, or willing, but hey. Join us for dinner after you’ve freshened up—guess what’s on the menu.”

“Could it be chicken and rice?” There were fifty dishes on the Safir’s official menu, but only chicken and rice was ever served.

“Holy shit, the man’s telepathic.”

“I’ll be down after slipping into something more comfortable.”

“Promises, promises, you tart.” Big Mac returned to the bar while I climbed up to the first landing—the elevators haven’t worked since 2001—the second, and the third. Through the window I looked across the oil-black Tigris at the Green Zone, lit up like Disneyland in Dystopia. I thought about J. G. Ballard’s novel High Rise, where a state-of-the-art London tower block is the vertical stage for civilization to unpeel itself until nothing but primal violence remains. A helicopter landed behind the Republican Palace, where this morning Mark Klimt had told us about the positive progress in Fallujah and elsewhere. What do Iraqis think about when they see this shining Enclave of Plenty in the heart of their city? I know, because Nasser, Mr. Khufaji, and others have told me: They think a well-lit, well-powered, well-guarded Green Zone is proof that the Americans doown a magic wand capable of restoring order to Iraq’s cities, but that anarchy makes a dense smokescreen behind which they can pipe away the nation’s oil. They’re wrong, but is their belief any more absurd than that of the 81 percent of Americans who believe in angels? I heard a miaownearby and looked down to see a moon-gray cat melting out of the shadows. I bent down to say hello, which was the one and only reason why I wasn’t scalped like a boiled egg when the explosion outside blew in the glass windows on the western face of the Safir Hotel, filling its unlit corridors with blast waves, filling our ear canals with solid roar, filling the spaces between atoms with the atonal chords of destruction.

I TAKE ANOTHER ibuprofen and sigh at my laptop screen. I wrote an account of the explosion on yesterday’s flight from Istanbul with dodgy guts and not enough sleep, and I’m afraid it shows: Nonfiction that smells like fiction is neither. A statement from Rumsfeld about Iraq is due at eleven A.M. East Coast time, but that’s fifty minutes away. I click on the telly to CNN World with the sound down, but it’s only a White House reporter discussing what “a well-placed source close to the secretary of defense” thinks Rumsfeld might say when he comes on. On her bed, Aoife yawns and puts down her Animal Rescue Ranger Annual 2004. “Daddy, can you put Dora the Exploreron?”

“No, poppet. I was just checking something for work.”

“Is that big white building in Bad Dad?”

“No, it’s the White House. In Washington.”

“Why’s it white? Do only white people live in it?”

“Er … Yes.” I switch the TV off. “Naptime, Aoife.”

“Are we right under Granddad Dave and Grandma Kath’s room?”

I should be reading to her, really—Holly does—but I have to get my article done. “They’re on the floor above us, but not directly overhead.”

We hear seagulls. The net curtain sways. Aoife’s quiet.

“Daddy, can we visit Dwight Silverwind after my nap?”

“Let’s not start that again. You need a bit of shut-eye.”

“You told Mummy you were going to take a nap too.”

“I will, but you go first. I have to finish this article and email it to New York by tonight.” And then tell Holly and Aoife that I won’t be atThe Wizard of Oz on Thursday, I think.

“Why?”

“Where d’you think money comes from to buy food, clothes, and Animal Rescue Rangerbooks?”

“Your pocket. And Mummy’s.”

“And how does it get in there?”

“The Money Fairy.” Aoife’s just being cute.

“Yeah. Well, I’m the Money Fairy.”

“But Mummy earns money at her job, too.”

“True, but London’s very expensive, so I need to earn as well.”

I think of a pithy substitute for the florid “spaces between atoms” line, but my inbox pings. It’s only from Air France, but when I get back to my article I’ve forgotten my pithy substitute.

“Why is London expensive, Daddy?”

“Aoife, please. I’ve got to work. Close your eyes.”

“Okay.” She lies down in a mock huff and pretends to snore like a Teletubby. It’s reallyannoying, but I can’t think of anything to say that’s sharp enough to shut Aoife up but not so sharp that she won’t burst into tears. Better wait this one out.

My first thought was, I type, I’m alive. My second—

“Daddy, why can’t I go to see Dwight Silverwind on my own?”

Don’t snap. “Because you’re only six years old, Aoife.”

“But I know the way to Dwight Silverwind’s! Out of the hotel, over the zebra crossing, down the pier, and you’re there.”

Look at mini-Holly. “Your fortune’s what you make it. Not what a stranger with a made-up name says. Now, please. Let me work.”

She snuggles up with her Arctic fox. Back to my article: My first thought was, I’m alive. My second thought was, Stay down; if it was a rocket-propelled grenade attack, there could be more. My—

“Daddy, don’t you want to know what’ll happen in your future?”

I let a displeased few seconds pass. “No.”

“Why not?”

“Because …” I think of Great-aunt Eilнsh’s mystic Script, and Nasser’s family, and Major Hackensack, and cycling along the Thames estuary footpath on a hot day in 1984 and recognizing a girl lying on the shingly beach, in her QuadropheniaT-shirt, her jeans as black as her cropped hair, and asleep, with a duffel bag as a pillow, and thinking, Cycle on, cycle on … And turning around. I shut my laptop, walk over to her bed, kick off my shoes, and lie down next to her. “Because what if I found out something bad was going to happen to me—or, worse, Mum, or you—but couldn’t change it? I’d be happier not knowing so I could just … enjoy the last sunny afternoon.”

Aoife’s eyes are big and serious. “What if you couldchange it?”