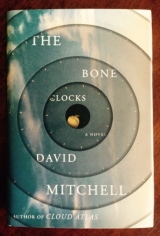

Текст книги "The Bone Clocks"

Автор книги: David Mitchell

Жанры:

Классическое фэнтези

,сообщить о нарушении

Текущая страница: 30 (всего у книги 40 страниц)

Holly puts her device back into her bag. “The police at home would never go to such trouble.” A cycle courier zips by and the traffic lurches forward. “How on earth did you find me, Officer?”

“Detective Marr,” says Brzycki. “Needles in haystacks really do get found. The precinct put out a Code Fifteen and although ‘slimbuilt female Caucasian in her fifties in a knee-length black raincoat’ hardly cuts the field down on a rainy day in Manhattan, your guardian angels were working overtime. Actually—it’s maybe not appropriate to say this at this time—but Sergeant Lewis up front there, he’s a bigfan of yours. He was giving me a lift back from Ninety-eighth down to Columbus Circle, and Lewis said, ‘My God, it’s her!’ Isn’t that right, Tony?”

“Sure is. I saw you speak at Symphony Space, Ms. Sykes, when The Radio Peoplewas out,” says the driver. “After my wife died, your book was a light in the darkness. It saved me.”

“Oh, I’m …” Holly is in such a state that this rheumatic story passes muster, “… glad it helped.” The meat truck draws up alongside. “And I’m very sorry for your loss.”

“Thanks for saying so, Ms. Sykes. Truly.”

After a few seconds, Holly menus her device. “I’ll device Sharon, my sister. She’s in England, but perhaps she can find out more about Aoife from there.”

The stream flickers and dims. The cord’s thinning,I subwarn Фshima. What have you found out about our host?

Her name’s Nancy, hates mice, she’s killed eight times,comes the delayed answer. A child soldier in South Sudan. This is her first job for Brzycki … Marinus, what’s “curarequinoline”?

Bad news. A toxin. One milligram can trigger a pulmonary collapse in ten seconds. Coroners never test for it. Why?

Nancy here and Brzycki have curarequinoline in their tranq guns. We can conclude it isn’t for self-defense.

“I’ll call my office again,” says Brzycki, helpfully. “See if they can’t get the name of your daughter’s hospital in Athens. Then at least you’ll have a direct line.”

“I can’t thank you enough.” Holly’s pale and sick-looking.

Brzycki flips down his wraparounds. “Anchor Two? Unit twenty-eight, you copying, Anchor Two?”

Unexpectedly, the earpiece in Nancy’s helmet comes to life, and through it I hear Immaculйe Constantin. “Clear as a bell. All things considered, let’s play safe. Eliminate your guest.”

Shock boils up but I rally myself: Ф shima, get her out!But my only reply is a blast of blizzard down the overstretched cord. Фshima can’t hear me, or he can’t respond, or both.

Clarity returns. “Copy that, Anchor Two,” Brzycki is saying, “but our present location is Fifth and East Sixty-eighth, where the traffic’s still at a dead halt. Might I advise that we postpone the last order as per—”

“Give the Sykes woman a tranq in each arm,” orders Constantin in her soft voice. “No postponement. Do it.”

I subshout hard, Ф shima, get her out get her out!

But no answer comes either from his soul or his inert body, propped up by mine on the bench, a block from the police car. All I can do is watch via the cord as an innocent woman, whom I lassoed into our War, is killed. I can’t transverse this distance, and even if I could I’d arrive too late.

“Understood, Anchor Two, will proceed as advised.” Brzycki nods at Lewis in the mirror, and at Nancy.

Holly asks, “Any luck with the hospital number, Detective Marr?”

“Our secretary’s on it.” Brzycki unholsters his tranq gun and flicks off the safety catch, while left-handed Nancy, through whose viewpoint I must watch, does the same.

“Why,” Holly’s voice changes, “do you need your guns?”

On reflex, I try to suasion Nancy to stop, but one cannot suasion down a cord and I just watch in horror as Nancy fires the tranq—at Brzycki’s throat, where a tiny red dot appears, on his Adam’s apple. The Anchorite touches it, astonished, then looks at the red dab on his fingers, looks at Nancy, utters, “What the …”

Brzycki slumps, dead. Lewis is shouting, as if under water, “Nancy, you outta your fuckin’ MIND?” or that’s what Nancy thinks she hears, as she finds herself taking Brzycki’s gun and firing it point-blank into Lewis’s cheek. Lewis huffs out a falsetto vowel of disbelief. Nancy, whom Фshima is suasioning ruthlessly, then finds herself clambering over Holly and onto the passenger seat as Lewis gibbers his last breath. She now cuffs herself to the steering wheel and unlocks the rear doors. As a parting gift, Фshima redacts a broad swath of Nancy’s present perfect and induces unconsciousness before egressing her and ingressing the traumatized Holly. Фshima psychosedates his new host immediately, and I watch Holly in the first person as she puts on her sunglasses, checks her head-wrap, climbs out of the squad car, and calmly walks back up Park Avenue toward the Frick. With a rip of corded feedback Фshima’s voice returns: Marinus, can you hear me?

I dare feel relief. Breathtaking, Ф shima.

War,subreplies the old warrior, and now, logistics. We have a retired author in distinctive headgear leaving a patrol car containing two dead fake cops and one living fake cop. Ideas?

Get Holly back here and rejoin your body,I subadvise Фshima. While you’re doing that, I’ll call L’Ohkna and ask for a catastrophic wipeout of all street cameras on the Upper East Side.

Фshima-in-Holly strides along. Can that dope fiend do that?

If a way exists, he’ll find it. If no way exists, he’ll make one.

Then what? 119A evidently isn’t the fortress it once was.

Agreed. We’ll go to earth at Unalaq’s. I’ll ask her to come and rescue us. I’m uncording now, see you soon. I open my eyes. My umbrella is still half hiding Фshima’s body and me, but a gray squirrel is sniffing my boot with curiosity. I swivel my foot. The squirrel is gone.

“HOME,” ANNOUNCES UNALAQ. She stops the car level with her front door, next to the Three Lives Bookstore on the corner of Waverly Place and West Tenth Street. Unalaq leaves the hazard lights on and helps me as I guide Holly across the pavement while Фshima stands guard like a monk-assassin. Holly’s still doped from the psychosedation, and we’ve drawn the attention of a tall thin man with a beard and wire-framed glasses. “Hey, Unalaq, is everything okay?”

“All good, Toby,” says Unalaq. “My friend just flew in from Dublin, but she’s terrified of flying, so she took a sleeping pill to knock her out. It worked a bit too well.”

“Sure did. She’s still cruising at twenty thousand feet.”

“Next time she’ll stick with the glass of white, I think.”

“Call down to the shop later. Your books on Sanskrit are in.”

“Will do, Toby, thanks.” Unalaq’s found her keys but Inez has already opened the door. Her face is taut with worry, as if her partner, Unalaq, is the breakable mortal and not her. Inez nods at Фshima and me and peers at Holly’s face with concern.

“She’ll be fine after a few hours’ sleep,” I say.

Inez’s expression says, I hope you’re right, and she goes to park the car in a nearby underground lot. Unalaq ushers us up the steps, inside, down the hallway, and into the tiny elevator. There’s not enough space for Фshima, who lopes up the stairs. I press up.

A dollar for your thoughts, subsays Unalaq.

One’s thoughts cost only a penny when I was Yu Leon.

Inflation, shrugs Unalaq, and her hair goes boing. Could Esther really be alive somewhere inside this head?

I look at Holly’s lined, taut, ergonomic face. She groans like a harried dreamer who can’t wake. I hope so, Unalaq. If Esther interpreted the Script correctly, then maybe. But I don’t know if I believe in the Script. Or the Counterscript. I don’t know why Constantin wants Holly dead. Or if Elijah D’Arnoq’s for real. Or if our handling of the Sadaqat issue is wrongheaded.“Truly, I don’t know anything,” I tell my five-hundred-year-old friend.

“At least,” Unalaq blows the end of a strand of copper hair from her nostril, “the Anchorites can’t exploit your overconfidence.”

HOLLY’S ASLEEP, ФSHIMA’S watching The Godfather Part II, Unalaq’s preparing a salad, and Inez has invited me to play her Steinway upright, as the piano tuner came yesterday. There’s a fine view of Waverly Place from the piano’s attic, and the small room is scented with the oranges and limes that Inez’s mother sends in crates from Florida. A photograph of Inez and Unalaq sits atop the Steinway. They’re posing in skiwear on a snowy peak, like intrepid explorers. Unalaq won’t have discussed the Second Mission with her partner, but Inez is no fool and must sense that something major is afoot. Being a Temporal who loves an Atemporal is surely as thorny a fate as being an Atemporal who loves a Temporal. It’s not just Horology’s future that my decisions this week will shape, but the lives of loved ones, colleagues, and patients who will get scarred if my companions and I never come back, just as Holly’s life was scarred by Xi Lo–in–Jacko’s death on the First Mission. If you love and are loved, whatever you do affects others.

So I leaf through Inez’s sheet music and choose Shostakovich’s puckish Preludes and Fugues. It’s fiendish but rewarding. Then I perform William Byrd’s Hughe Ashton’s Groundas a palate cleanser, and a handful of Jan Johannson’s Swedish folk songs, just because. From memory I play Scarlatti’s K32, K212, and K9. The Italian’s sonatas are an Ariadne’s thread that connects Iris Marinus-Fenby, Yu Leon Marinus, Jamini Marinus Choudary, Pablo Antay Marinus, Klara Marinus Koskov, and Lucas Marinus, the first among my selves to discover Scarlatti, back in his Japanese days. I traded the sheet music off de Zoet, I recall, and was playing K9 just hours before my death in July 1811. I’d felt my death approaching for several weeks, and had put my affairs in order, as they used to say. My friend Eelattu cut me adrift with a phial of morphine I’d reserved for the occasion. I felt my soul sinking up from the Light of Day, up onto the High Ridge, and wondered where I’d be resurrected. In a wigwam or a palace or an igloo, in a jungle or tundra or a four-poster bed, in the body of a princess or a hangman’s daughter or a scullery maid, forty-nine spins of the earth later …

… in a nest of rags and rotten straw, in the body of a girl burning with fever. Mosquitoes fed on her, she was crawling with lice, and weakened by an intestinal parasite. Measles had dispatched the soul of Klara, my new body’s previous inhabitant, and it was three days before I could psychoheal myself sufficiently to take proper stock of my surroundings. Klara was the eight-year-old property of Kiril Andreyevich Berenovsky, an absentee landlord whose estate was bounded by a pendulous loop in the Kama River, Oborino County, Perm Province, the Russian Empire. Berenovsky returned to his ancestral lands only once a year to bully the local officials, hunt, bed virgins, and exhort his bailiff to bleed the estate even whiter than last year. Happiness did not enter feudal childhoods, and Klara’s was miserable even by the standards of the day. Her father had been killed by a bull, and her mother was crushed by a life of childbearing, farmwork, and a peasant moonshine known as rvota, or “puke.” Klara was the last and least of nine siblings. Three of her sisters had died in infancy, two others had gone to a factory in Ekaterinburg to settle a debt of Berenovsky’s, and her three brothers had been sent to the Imperial Army just in time to be butchered at the Battle of Eylau. Klara’s recovery from death was greeted with joyless fatalism. It was a long fall indeed from Lucas Marinus’s life as a surgeonscholar to Klara’s dog-eat-dog squalor, and it was going to be a long, fitful, fretful climb back up the social ladder, especially in a female body in the early nineteenth century. I did not yet possess any psychosoteric methods to speed this ascent. All Klara had was the Russian Orthodox Church.

Father Dmitry Nikolayevich Koskov was a native of Saint Petersburg who baptized, preached to, wed, and buried the four hundred serfs on the Berenovksy estate, as well as the three dozen freeborn workers who lived and worked there. Dmitry and his wife, Vasilisa, lived in a rickety cottage overlooking the river. The Koskovs had arrived in Oborino County ten years before, full of youth and a philanthropic zeal to improve the lives of the rural peasantry. Long before I-in-Klara entered their lives, that zeal had been killed by the drudgery and bestiality of life in the Wild East. Vasilisa Koskov suffered from severe depression and a conviction that the world was laughing at her childlessness behind her back. Her only friends on the estate were books, and books can talk but do not listen. Dmitry Koskov’s ennui matched his wife’s and he cursed himself, daily if not hourly, for having forfeited the prospects of clerical life in Saint Petersburg, where his wife and his career could have blossomed. His yearly petitions to the church authorities for a pulpit closer to civilization proved fruitless. He was, as we’d say now, seriously Out of the Loop. Dmitry had God, but why God had condemned him and Vasilisa to sink in a bog of superstition and spite and sin like Oborino County for a landlord like Berenovsky, who showed more concern for his hounds than his serfs, the Almighty did not share.

To me-in-Klara, the Koskovs were perfect.

ONE OF KLARA’S chores, as soon as she was well again, was to deliver eggs to the bailiff, the blacksmith, and the priest. One morning in 1812, as I handed Vasilisa Koskov her basket of eggs at the kitchen door, I asked her shyly if it was really true I’d meet my dead sisters in heaven. The priest’s wife was taken aback, both that the near-mute serf girl had spoken, and that I’d asked such a rudimentary question. Didn’t I listen to Father Koskov in church every Sunday? I explained that the boys pinched my arm and tugged my hair to stop me listening to God’s Word, so although I wanted to hear about Jesus, I couldn’t. Yes, I was mawkishly, hawkishly manipulating a lonely woman for my own gain, but the alternative was a life of bovine labor, piggish servitude, and bile-freezing winters. Vasilisa brought me into her kitchen, sat me down, and taught me how Jesus Christ had come to earth in the body of a man to allow us sinners to go to heaven after we died, so long as we said our prayers and behaved as good Christians.

I nodded gravely, thanked her, then asked if it was true the Koskovs were from Petersburg. Soon Vasilisa was reminiscing about the operas, the Anichkov Theater, the balls at this archduke’s name day, the fireworks at that countess’s ball. I told her I had to go, because my mother would beat me for taking too long, but the next time I delivered the eggs, Vasilisa served me real tea from her samovar sweetened with a spoonful of apricot jam. Nectar! Soon the melancholic priest’s melancholic wife found herself discussing her private disappointments. The little serf listened with wisdom far beyond her eight years. One fine day, I took a gamble and told Vasilisa about a dream I’d had. There was a lady with a blue veil, milky skin, and a kind smile. She had appeared in the hut I shared with my mother, and told me to learn to read and write, so that I could take her son’s message to serfs. Stranger still, the kind lady had spoken strange words in a language I didn’t understand, but they had stayed glowing in my memory, just the same.

What could it possibly mean, Mrs. Vasilisa Koskov?

PLEASED AS VASILISA’S husband was by the improvement in his wife’s nerves, Dmitry Nikolay was anxious about her being suckered yet again by yet another wily peasant. So the cleric interviewed me in the empty church. I wore a shy bewilderment at being noticed, let alone spoken to, by so august a figure, even as I nudged Dmitry towards a belief that here was a child destined for a higher purpose, a purpose that he, Father Dmitry Koskov, had been chosen to oversee. He asked me about my dream. Could I describe the lady I had seen? I could. She had dark brown hair, a lovely smile, a blue veil, no, not white, not red, but blue, blue like the sky in summer. Father Dmitry asked me to repeat the “strange words” the lady had told me. Little Klara frowned, and very shyly confessed that the words didn’t sound like Russian words. Yes, yes, said Father Dmitry, his wife had said as much; but what were these words? Could I remember any? Klara shut her eyes and quoted, in Greek, Matthew 19:14: But Jesus said, Suffer little children, and forbid them not, to come unto me: for such is of the kingdom of heaven.

The priest’s eyes and mouth opened and stayed open.

Trembling, I said I hoped the words meant nothing bad.

My conscience was clean. I was an epiphyte, not a parasite.

A few days later, Father Dmitry approached Sigorsky, the estate bailiff, to propose that Klara be allowed to live in their house, in order for his wife to train the girl as a servant for the Berenovksy house and give her a rudimentary schooling. Sigorsky granted this unusual request as pro bono payment for Father Dmitry averting his priestly gaze from the bailiff’s assorted scams. I had no goods to bring with me to the Koskovs’ cottage but a sackcloth dress, clogs, and a filthy sheepskin coat. That night Vasilisa gave me the first hot bath I’d enjoyed since my death in Japan, a clean frock, and a woolen blanket. Progress. While I was bathing, Klara’s mother appeared, demanding a rouble “for compensation.” Dmitry paid, on the understanding that she would never ask for another. I saw her around the estate, but she never acknowledged me, and the following winter, she fell drunk into a frozen ditch at night and never woke up.

Even a benign Atemporal cannot save everyone.

THE CLAIM IS immodest, but as a de facto if not a de jure daughter, I’d brought purpose and love back into the Koskovs’ life. Vasilisa set up a class in the church to teach the peasant children their ABBs, basic numeracy, and scripture, and found time in the evening to teach me French. Lucas Marinus had spoken the language in my previous life, so I made a gratifyingly quick-learning student. Five years passed, I grew tall and strong, but every summer when Berenovksy visited, I dreaded his noticing me in church, and asking why his serf was being given airs above her natural station. In order to protect my gains and carry on climbing, my benefactors needed a benefactor.

Dmitry’s uncle, Pyotr Ivanovich Chernenko, was the obvious, indeed the only, candidate. Nowadays he would be fкted as a self-made entrepreneur, with a gossip-magazine private life, but as a young man in nineteenth-century Saint Petersburg he had caused a scandal by eloping with and, even worse, marrying an actress five years his senior. Dissipation and disgrace had been gleefully predicted, but Pyotr Ivanovich instead had made first one fortune by trading with the British against the continental blockade, and was now making another by introducing Prussian smelters to foundries throughout the Urals. His love marriage had stayed strong, and the two Chernenko sons were students in Gothenburg. I persuaded Vasilisa that Uncle Pyotr must be invited to our cottage to inspect her estate school when he was next in Perm on business.

He arrived one morning in autumn. I ensured I shone. Uncle Pyotr and I spoke for an hour on metallurgy alone. Pyotr Ivanovich Chernenko was a shrewd man who had seen and learned a lot from his five decades of life, but he was beguiled by a serf girl who was so conversant on such manly concerns as commerce and smelting. Vasilisa said that the angels must whisper things in my ears as I slept. How else could I have acquired German andFrench so quickly, or known how to set a broken bone, or have grasped the principles of algebra? I blushed and mumbled about books and my elders and betters.

That night as I lay in bed I heard Uncle Pyotr Ivanovich tell Dmitry, “One bad-tempered whim of that ass Berenovksy, nephew, is all it needs to condemn the poor girl to a life of planting turnips in frozen mud and the spousal bed of a tusked hog. Something must be done! Something shall be done!” Uncle Pyotr left the next day in never-ending rain-spring and autumn alike are muddy hell in Russia-telling Dmitry that we had rotted away in this backwater for far too long already …

· · ·

THE WINTER OF 1816 was pitiless. Dmitry buried about fifteen peasants in the iron-hard sod, the Kama River froze, the wolves grew bold, and even priests and their families went hungry. Spring refused to show until the middle of April, and the mail coach from Perm didn’t resume its regular visits to Oborino County until May 3. Klara Marinus’s journal marks this as the date when two official-looking letters were delivered to the Koskovs’ cottage. They stayed on the mantelpiece until Dmitry returned in the late afternoon from administering last rites to a woodcutter’s son, who had died of pleurisy several miles away. Dmitry opened the first letter with his paper knife and his face reflected the momentousness of its news. He puffed out his cheeks, said, “This affects you, Klara, my dear,” and read it aloud: “ ‘Kiril Andreyvich Berenovsky, Master of the Berenovksy Estate in the Province of Perm, hereby grants to the female serf Klara, daughter of the deceased serf Gota, full and unconditional liberty as a subject of the Emperor, in perpetuity.’ ” In my memory, cuckoos are calling across the river and sunshine floods the Koskovs’ little parlor. I asked Dmitry and Vasilisa if they would consider adopting me. Vasilisa smothered me in a tearful hug while Dmitry coughed, examined his fingers, and said, “I dare say we could manage that, Klara.” We knew that only Pyotr Ivanovich could have brought about this administrative miracle, but some months would pass before we learned exactly how. My freedom had been granted in exchange for Uncle Pyotr settling my owner’s account with his vintner.

In our excitement, we’d forgotten the second envelope. This contained a summons from the Episcopal Office of the Bishop of Saint Petersburg, requesting Father Dmitry Koskov to take up his new post as priest at the Church of the Annunciation of the Blessed Virgin on Primorsky Prospect, Saint Petersburg, on or before July 1 of that year. Vasilisa asked, quite seriously, if we were dreaming. Dmitry handed her the letter. As Vasilisa read it, she grew ten years younger before our eyes. Dmitry said he shuddered to think what Uncle Pyotr had paid for such a plum post. The answer was a consignment of Sienna marble to a pet monastery of the patriarch’s but, again, we didn’t hear this from Pyotr Ivanovich’s lips. Human cruelty can be infinite. Human generosity can be boundless.

NOT SINCE THE late 1780s had I lived in a sophisticated European capital, so once we were installed in our new house by Dmitry’s church in Saint Petersburg, I engorged myself on music, theater, and conversation, as best a thirteen-year-old freed serf girl could. While I was expecting my lowly origins to be an obstacle in society, they ended up enhancing my status as an event of the season on the novelty-hungry Petersburg salon circuit. Before I knew it, “Miss Koskov the Polymath of Perm” was being examined in several languages on many disciplines. I gave my foster mother due credit for my “corpus of knowledge,” explaining that once she had taught me to read I could harvest at will the fruits of the Bible, dictionaries, almanacs, pamphlets, suitable poetry, and improving literature. Emancipationists cited Klara Koskov to argue that serfs and their owners differed only by accident of birth, while skeptics called me a goose bred for foie gras, stuffed with data I merely regurgitated without understanding.

One day in October a coach pulled by four white thoroughbreds pulled up on Primorsky Prospect, and the equerry of Tsarina Elizabeth delivered to my family a summons to the Winter Palace for an audience with the Tsarina. Neither Dmitry nor Vasilisa slept a wink and were awed by the succession of sumptuous chambers we passed through on our journey to the Tsarina’s apartment. My metalife had inoculated me against pomp centuries ago. Of Tsarina Elizabeth, I best recall her sad bass clarinet of a voice. My foster parents and I were seated on a long settle by a fire, while Elizabeth favored a high-backed chair. She asked questions in Russian about my life as a serf, then switched to French to probe my grasp of a variety of subjects. In her native German, she supposed that my round of engagements must be rather tiresome? I said that while an audience with a tsarina could never be tiresome, I would not be sorry when I was yesterday’s news. Elizabeth replied that I now knew how an empress feels. She had the newest pianoforte from Hamburg and asked if I cared to try it out. So I played a Japanese lullaby I’d learned in Nagasaki, and it moved her. Apropos of I’m not sure what, Elizabeth asked me what sort of husband I dreamed of. “Our daughter is still a child, Your Highness,” Dmitry found his tongue, “with a headful of girlish nonsense.”

“I was wedded by my fifteenth birthday.” The Tsarina turned to me and Dmitry lost his tongue again.

Matrimony, I remarked, was not a realm I yearned to enter.

“Cupid’s aim is unerring,” Elizabeth said. “You’ll see. You’ll see.”

After a thousand years, dear Tsarina, I did not retort, his arrows tend to bounce off me. I agreed that no doubt Her Highness spoke the truth. She knew a fudged answer when she heard it, and suggested that I preferred books to husbands. I agreed that books tended not to switch their stories whenever it suited them. Dmitry and Vasilisa shifted in their borrowed finery. The jaded queen of a court in which adultery was a form of entertainment looked through me, the gold of the fire toying with the gold of her hair. “What an old sentence,” she said, “from such youthful lips.”

OUR VISIT TO the royal court triggered a new wave of gossip about Klara Koskov’s true paternity that caused embarrassment for my foster father, so we brought my brief career as a salon curiosity to a timely close. Our decision coincided with Uncle Pyotr’s return from a half year in Stockholm, and the Chernenko residence on Dzerzhinsky Street became a second home for us. Pyotr’s ex-actress wife, Yuliya Grigorevna, became a loyal friend and held dinners where I met a broader cross section of Petersburgers than I had in the higher stratum of the salons. Bankers, chemists, and poets rubbed shoulders with theater managers, clerks, and sea captains. I continued to read voraciously, and wrote to many authors, signing myself “K. Koskov” to conceal my age and gender. Horology’s archives still contain letters to K. Koskov from the physician Renй Laлnnec, the inventor Humphrey Davy, and the astronomer Giuseppe Piazzi. University was not yet a possibility for women, but as the years passed, many of the liberal-leaning Petersburg intelligentsia visited the Chernenkos to discuss their papers with the cerebral bluestocking. In time, I even received a few marriage proposals, but neither Dmitry nor Vasilisa Koskov was eager to lose me, and I had no desire to become a man’s legal property for a second time.

KLARA’S TWENTIETH CHRISTMAS came, and her twelfth with the Koskovs. She received fur-lined boots from Dmitry, piano music from Vasilisa, and a sable cloak from the Chernenkos. My journal records that on January 6, 1823, Dmitry gave a sermon on Job and the hidden designs of Providence. The choir of the Church of the Annunciation of the Blessed Virgin gave only a mediocre performance due to sore throats and colds. Snow lay deep in the gutters, fog and smoke filled the alleyways, the sun was a memory, icicles hung from the eaves, steam snorted white from the horses’ frozen nostrils, and ice floes as big as boats floated on the thundercloudgray Neva River.

After our midday meal, Vasilisa and I were in the parlor. I was writing a letter in Dutch about osmosis in giant trees to a scholar at Leiden University. My foster mother was marking the French compositions of some of her pupils. The fire gnawed logs. Galina, our housekeeper, was lighting the lamps and tutting about my eyesight when we heard a knock at our door. Jasper, our little dog of uncertain pedigree, went skating and yapping down the hall. Vasilisa and I looked at each other but neither of us was expecting a caller. Through the lace curtain we saw an unknown coach with a veiled window. Galina brought in a card, given to her by a footman at the door. Dubiously, my mother read it aloud: “Mr. Shiloh Davydov. ‘Shiloh’? It sounds foreign to me. Does it sound foreign to you, Klara?” Davydov’s address, however, was the respectable Mussorgky Prospect. “Might they be friends of Uncle Pyotr’s?”

“ Mrs. Davydov is in the coach, too, I’m told,” added Galina.

With a sudden change of mind that I would later recognize as an Act of Suasion, Vasilisa’s doubts evaporated. “Well, invite them in, Galina! What must they think of us? The poor lady’ll be freezing!”

“PARDON OUR UNANNOUNCED intrusion,” said a spry man with expansive whiskers, a plangent voice, and dark clothes of a foreign cut, “Mrs. and Miss Koskov. The fault is all mine. I had my letter of introduction written before church, but then our stable boy got kicked by a horse and we had to summon a doctor. With all this brouhaha afoot, I quite neglected to ensure that the letter I had written had in fact been brought to you. My name is Shiloh Davydov, and I am at your service.” He handed his hat to Galina with a smile. “Of Russian extraction from my father, but resident in Marseille, in so far as I am ‘resident’ anywhere. And may I,” even then, I noticed a Chinese cadence to his Russian, “may I present my wife, Mrs. Claudette Davydov, who, Miss Koskov, is better known to you”—he waggled his cane—“by her maiden and pen-name ‘C. Holokai.’ ”

This was unexpected. I had corresponded with “C. Holokai,” author of a philosophical text on the Transmigration of the Soul, several times, never dreaming that he might be a she. Mrs. Davydov’s dark, inquisitive face hinted at Levantine or Persian extraction. She was dressed in dove-gray silk and wore a necklace of black and white pearls. “Mrs. Koskov,” she addressed Vasilisa, “thank you for your hospitality to two strangers on a winter’s afternoon.” She spoke Russian more slowly than her husband, but enunciated with such great care that her listeners paid close attention. “We should have waited until tomorrow before inviting you to our house, but the name of ‘K. Koskov’ came up only an hour ago at the house of Professor Obel Andropov and I took it as a—as a sign.”