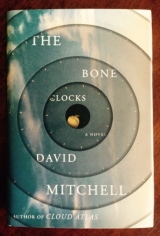

Текст книги "The Bone Clocks"

Автор книги: David Mitchell

Жанры:

Классическое фэнтези

,сообщить о нарушении

Текущая страница: 10 (всего у книги 40 страниц)

MY RIGHT FOOT hits the ground first, but my left one’s gone AWOL, and I’m cartwheeling, my body mapped by local explosions of pain—ankle, knee, elbow —shit, my left ski’s gone, whipped off, vamoosed—ground-woods-sky, ground-woods-sky, ground-woods-sky, a faceful of gravelly snow; dice in a tumbler; apples in a tumble dryer; a grunt, a groan, a plea, a shiiiiiiiiit … Gravity, velocity, and the ground; stopping is going to cost a fortune and the only acceptable currency is pain—

OUCH. WRIST, SHIN, rib, butt, ankle, earlobe … Sore, walloped, sure … but unless I’m too doped on natural painkillers to notice, nothing’s broken. Flat on my back in a crash-mat of snow, pine needles, and mossy, stalky mulch. I sit up. My spine still works. That’s always useful. My watch is still working, and it’s 16:10, just as it should be. Tiny silver needles of birdsong. Can I stand? I have an ache instead of a right buttock; and my coccyx feels staved in by a geologist’s hammer … But, yes, I can stand, which makes this one of my luckiest escapes. I lift my goggles, brush the snow off my jacket, unclip the ski I still have and use it as a staff to hobble uphill, searching for its partner. One minute, two minutes, still no joy. Chetwynd-Pitt will be giving the fluffy snowman a victory punch down in the village just about now. I backtrack, searching through the undergrowth along the side of the piste. There’s no dishonor in taking a fall on a black run—it’s not as if I’m a professional or a ski instructor—but returning to chez Chetwynd-Pitt forty minutes after Fitzsimmons and Quinn with one ski missing would be, frankly, crap.

Here comes a whooshing sound—another skier—and I stand well back. It’s the French girl from the viewing platform—who else wears mint green this season? She takes the rise as gracefully as I was elephantine, lands like a pro, sees me, takes in what’s happened, straightens up, and stops a few meters away on the far side of the piste. She bends down to retrieve what turns out to be my ski and brings it over to me. I muster my mediocre French: “Merci … Je ne cherchais pas du bon cфtй.”

“Rien de cassй?”

I think she’s asking if I’ve broken anything. “Non. А part ma fiertй, mais bon, зa ne se soigne pas.”

She hasn’t removed her goggles so, apart from a few loose strings of wavy black hair and an unsmiling mouth, my Good Samaritaness’s face stays unseen. “Tu en as eu, de la veine.”

I’m a jammy bugger? “Tu peux …” “Bloody well say that again,” I’d like to say. “C’est vrai.”

“Зa ne rate jamais: chaque annйe, il y a toujours un couillon qu’on vient ramasser а la petite cuillиre sur cette piste. Il restera toute sa vie en fauteuil roulant, tout зa parce qu’il s’est pris pour un champion olympique. La prochaine fois, reste sur la piste bleu.”

Jesus, my French is rustier than I thought: “Every year someone breaks their spine and I ought to stick to the blue piste”? Something like that? Whatever it was, she launches herself without a goodbye and she’s gone, swooping through the curves.

BACK AT CHETWYND-PITT’S chalet, floating in the tub, Nirvana’s Nevermindthumping through the walls, I smoke a joint among the steam serpents and peruse the Case of the Body-Hopping Mind for the thousandth time. The facts are deceptively simple: Six nights ago, outside my parents’ home, I encountered one mind in possession of someone else’s body. Weird shit needs theories and I have three.

Theory 1: I hallucinated both the second coming of the Yeti and his secondary proofs, like his footprints and those statements that only Miss Constantin—or I—could have known about.

Theory 2: I am the victim of a stunningly complex hoax, involving Miss Constantin and an accomplice who poses as a homeless man.

Theory 3: Things are exactly as they appear to be, and “mind-walking”—what else to call it?—is a real phenomenon.

The Hallucination Theory: “I don’t feel insane” is a feeble retort, but I really don’t. If I was hallucinating a character so vividly, surely I’d be hallucinating other things too? Like hearing, I don’t know, Sting singing “An Englishman in New York” from inside lightbulbs.

The Complex Hoax Theory: “Why me?” Some people may hold a grudge against Marcus Anyder, if certain fictions were known. But why seek revenge via some wacky plot to loosen my grip on sanity? Why not just kick the living shit out of me?

The Mind-walking Theory: Plausible, ifyou live in a fantasy novel. Here, in the real world, souls stay inside the body. The paranormal is always, alwaysa hoax.

Water drops go plink, plink, plinkfrom the tap. My palms and fingers are pink and wrinkly. Someone’s thumping upstairs.

So what do I do about Immaculйe Constantin, the Yeti, and the weird shit? The only possible answer is “Nothing, for now.” Perhaps I’ll be served another slice tonight, or perhaps it’s waiting for me back in London or Cambridge, or perhaps this will just be one of life’s dangly plot lines that one never revisits. “Hugo?” It’s Olly Quinn, bless him, knocking on the door. “You still alive in there?”

“Yes, the last time I checked,” I shout, over Kurt Cobain.

“Rufus says we should get going before Le Croc fills up.”

“You three go on ahead and get a table. I’ll be along soon.”

LE CROC—A.K.A. LE Croc of Shit to its regulars—is a badger’s set of a drinking hole down an alley off the three-sided plaza in Sainte-Agnиs. Gьnter, the owner, gives me a mock salute and points to the Eagle’s Nest—a tiny mezzanine cubbyhole occupied by my three fellow Richmondians. It’s gone ten, the place is chocka, and Gьnter’s two saisonniers—one skinny girl in Hamlet black, the other plumper, frillier, and blonder—are busy with orders. Back in the 1970s Gьnter was ranked the 298th best tennis player in the world (for a week) and has a framed clipping to prove it. Now he supplies cocaine to wealthy Eurotrash, including Lord Chetwynd-Pitt’s eldest scion. His Andy Warhol flop of bleached hair is stylistic self-immolation, but a Swiss-German drug dealer in his fifties does not welcome fashion advice from an Englishman. I order a hot red wine and climb to the Nest, past a copse of seven-foot Dutchmen. Chetwynd-Pitt, Quinn, and Fitzsimmons have eaten—Gьnter’s daube, a beef stew, and a wedge of apple pie with cinnamon sauce—and have started on the cocktails which, thanks to my lost bet, I have the honor of buying for Chetwynd-Pitt. Olly Quinn’s tanked and glassy-eyed. “Can’t get my head round it,” he’s saying morosely. The boy’s a crap drunk.

“Can’t get your head round what?” I take off my scarf.

Fitzsimmons mouths, “Ness.”

I mime hanging myself with my scarf, but Quinn doesn’t notice: “We’d plannedit. I’d drive her to Greenwich, she’d introduce me to Mater and Pater. I’d see her over Christmas, we’d go to Harrods for the sales, skate on the rink at Hyde Park Corner … It was all planned. Then that Saturday, after I took Cheeseman to hospital for his stitches, she calls me up and it’s ‘We’ve come to the end of the road, Olly.’ ” Quinn swallows. “I’m like … huh? Shewas all, ‘Oh, it’s not your fault, it’s mine.’ She said she’s feeling conflicted, tied-down, and—”

“I know a Portuguese tart who enjoys that tying-down stuff, if that oils your rooster,” says Chetwynd-Pitt.

“Misogynist andunfunny,” says Fitzsimmons, inhaling vapors from his vin chaud. “Splitting up’s an utter bitch.”

Chetwynd-Pitt sucks a cherry. “Specially if you buy an opal necklace Christmas prezzie and get dumped before you can turn the gift into sex. Was it from Ratners Jewellers, Olly? They issue gift tokens for returned items, but not cash. Our groundsman had a wedding called off, that’s how I know.”

“No, it wasn’t from bloody Ratners,” growls Quinn.

Chetwynd-Pitt lets the cherry stone drop into the ashtray. “Oh cheer up, for shitsake. Sainte-Agnиs plus New Year equals more Europussy than the Schleswig-Holstein Feline Rescue Society would know what to do with. And I’ll bet you a thousand quid that the feeling-conflicted line means she’s got another boyfriend.”

“Not Ness, no way,” I reassure poor Quinn. “She respects you—and herself—way too much. Trust me. And when Lou dumped you,” this is for Chetwynd-Pitt, “you were a train wreck for months.”

“Lou and I were serious. Olly ’n’ Ness lasted what, all of five weeks? And Lou didn’t dump me. It was mutual.”

“Six weeks, four days.” Quinn looks tortured. “But it’s not time that matters. It felt … like a secret place just us two knew about.” He drinks his obscure Maltese beer. “She fittedme. I don’t know what love is, whether it’s mystical or chemical or what. But when you have it, and it goes, it’s like a … it’s like … it’s …”

“Cold turkey,” says Rufus Chetwynd-Pitt. “Roxy Music were right about love being thedrug, and when your supply’s used up, no dealer on earth can help you. Well: There isone—the girl. But she’s gone and won’t see you. See? I doknow what poor Olly’s suffering. What I’d prescribe is”—he waggles his empty cocktail glass—“an Angel’s Tit. Crиme de cacao,” he tells me, “and maraschino. Pile au bon moment, Mo nique, tu as des pouvoirs tйlйpathiques.” The plumper waitress arrives with my hot wine, and Chetwynd-Pitt deploys his smart-arse French: “Je prendrai une Alien Urine, et ce sera mon ami ici prйsent”—he nods at me—“qui rйglera l’ardoise.”

“Bien,” says Monique, acting bubbly. “J’aimerais bien moi aussi avoir des amis comme lui. Et pour ces messieurs? Ils m’ont l’air d’avoir encore soif.” Fitzsimmons orders a cassis, and Olly says, “Just another beer.” Monique gathers the used dishes and glasses and off she’s gone.

“Well, I’d fire my unsawn-off shotgun up that,” says Chetwynd-Pitt. “A cuddly six and a half. Yummier than that Wednesday Adams lookalike Gьnter’s also taken on. Frightmare or what?” I follow his gaze down to the skinnier bargirl. She’s filling a schooner of cognac. I ask if she’s French, but Chetwynd-Pitt’s asking Fitzsimmons, “You’re the answer man tonight, Fitz. What’s this love malarkey all about?”

Fitzsimmons lights a cigarette and passes us the box. “Love is the anesthetic applied by Nature to extract babies.”

I’ve heard that line elsewhere. Chetwynd-Pitt flicks ash into the tray. “Can you do better than that, Lamb?”

I’m watching the skinny barmaid making what must be Chetwynd-Pitt’s Alien Urine. “Don’t ask me. I’ve never been in love.”

“Oh, listen to the poor lamb,” mocks Chetwynd-Pitt.

“That’s crap,” says Quinn. “You’ve had lots of girls.”

Memory hands me a photo of Fitzsimmons’s yummy mummy. “Anatomically, I have some knowledge, sure—but emotionally they’re the Bermuda Triangle. Love, that drug Rufus referred to, that state of grace Olly pines for, that great theme … I’m immune to it. I have not once felt love for any girl. Or boy, for that matter.”

“That’s a pile of steaming bollocks,” says Chetwynd-Pitt.

“It’s the truth. I’ve never been in love. And that’s okay. The colorblind get by just fine not knowing blue from purple.”

“You can’t have met the right girl,” decides Quinn the idiot.

“Or met too many right girls,” suggests Fitzsimmons.

“Human beings,” I inhale my wine’s nutmeggy steam, “are walking bundles of cravings. Cravings for food, water, shelter, warmth; sex and companionship; status, a tribe to belong to; kicks, control, purpose; and so on, all the way down to chocolate-brown bathroom suites. Love is one way to satisfy some of these cravings. But love’s not just the drug; it’s also the dealer. Love wants love in return, am I right, Olly? Like drugs, the highs look divine, and I envy the users. But when the side effects kick in—jealousy, the rages, grief, I think, Count me out. Elizabethans equated romantic love with insanity. Buddhists view it as a brat throwing a tantrum at the picnic of the calm mind. I—”

“I spy an Alien Urine.” Chetwynd-Pitt smirks at the skinny barmaid and the tall glass of melon-green gloop on her tray. “J’espиre que ce sera aussi bon que vos Angel’s Tits.”

“Les boissons de ces messieurs.” Lips thin and unlipsticked, with a “messieurs” that came sheathed in irony. She’s gone already.

Chetwynd-Pitt sniffs. “There goes Miss Charisma 1991.”

The others clink their glasses while I hide one of my gloves behind a pot-plant. “Maybe she just doesn’t think you’re as witty as you think you are,” I tell Chetwynd-Pitt. “How does your Alien Urine taste?”

He sips the pale green gloop. “Exactly like its name.”

THE TOURIST SHOPS in Sainte-Agnиs’s town square—ski gear, art galleries, jewelers, chocolatiers—are still open at eleven, the giant Christmas tree’s still bright, and a cr к pier, dressed as a gorilla, is doing a brisk trade. Despite the bag of coke Chetwynd-Pitt just scored off Gьnter, we decide to put off Club Walpurgis until tomorrow night. It’s beginning to snow. “Damn,” I say, turning back. “I left a glove at Le Croc. You guys get Quinn home, I’ll catch you up …”

I hurry back down the alley and get to the bar as a large party of He-Norses and She-Norses leaves. Le Croc has a round window; through it I can see the skinny barmaid preparing a jug of Sangria without being seen. She’s very watchable, like the motionless bass player in a hyperactive rock band. She combines a fuck-you punkishness with a precision about even her smallest actions. Her will would be absolutely unswayable, I sense. As Gьnter takes the jug away into Le Croc’s interior she turns to look at me so I enter the smoky clamor and make my way between clusters of drinkers to the bar. After she’s wiped the frothy head off a glass of beer with the flat of a knife and handed it to a customer, I’m there with my forgotten glove gambit. “Dйsolй de vous embкter, mais j’йtais installй lа-haut”—I point to the Eagle’s Nest, but she doesn’t yet give away whether or not she remembers me—“il y a dix minutes et j’ai oubliй mon gant. Est-ce que vous l’auriez trouvй?”

Cool as Ivan Lendl slotting in a lob above an irate hobbit, she reaches down and produces it. “Bizarre, cette manie que les gens comme vous ont d’oublier leurs gants dans les bars.”

Fine, so she’s seen through me. “C’est surtout ce gant; зa lui arrive souvent.” I hold up my glove like a naughty puppet and ask it scoldingly, “Qu’est-ce qu’on dit а la dame?” Her stare kills my joke. “En tout cas, merci. Je m’appelle Hugo. Hugo Lamb. Et si pour vous, зa fait”—shit, what’s “posh” in French?—“chic, eh bien le type qui ne prend que des cocktails s’appelle Rufus Chetwynd-Pitt. Je ne plaisante pas.” Nope, not a flicker. Gьnter reappears with a tray of empty glasses. “Why do you speak French with Holly, Hugo?”

I look puzzled. “Why wouldn’t I?”

“He seemed keen to practice his French,” says the girl, in London English. “And the customer isalways right, Gьnter.”

“Hey, Gьnter!” An Australian calls over from the bar football. “This bastard machine’s playing funny buggers! I fed it my francs but it’s not giving me the goods.” Gьnter heads over, Holly loads up the dishwasher, and I work out what’s happened. When she returned my ski on the black run earlier, she used French, but she said nothing when my accent gave me away because if you’re female and working in a ski resort you must get hit on five times a day, and speaking French with Anglophones strengthens the force field. “I just wanted to say thanks for returning my ski earlier.”

“You already did.” Working-class background; unintimidated by rich kids; very good French.

“This is true, but I’d be dying of hypothermia in a lonely Swiss forest if you hadn’t rescued me. Could I buy you dinner?”

“I’m working in a bar while tourists are eating their dinner.”

“Then could I buy you breakfast?”

“By the time you’re having breakfast, I’ll have been mucking out this place for two hours, with two more hours to go.” Holly slams shut the glass-washer. “Then Igo skiing. Every minute spoken for. Sorry.”

Patience is the hunter’s ally. “Understood. Anyway, I wouldn’t want your boyfriend to misinterpret my motives.”

She pretends to fiddle with something under the counter. “Won’t your friends be waiting for you?”

Odds of four to one there’s no boyfriend. “I’ll be in town for ten days or so. See you around. Good night, Holly.”

“G’night,” and piss off, add her spooky blue eyes.

December 30

THE BAYING OF THE PARISIAN MOB drains into the drone of a snowplow, and my search through French orphanages for the Cyclops-eyed child ends with Immaculйe Constantin in my tiny room at the family Chetwynd-Pitt’s Swiss chalet telling me gravely, You haven’t lived until you’ve sipped Black Wine, Hugo. Then I’m waking up in the very same garret groinally attached to a mystifying dawn horn as big as a cruise missile. A bookshelf, a globe, a Turkish gown hanging from the door, a thick curtain. “This is where we put the scholarship boys,” Chetwynd-Pitt only half joked when I first stayed here. The old pipe lunks and clanks. Dope + Altitude = Screwy Dreams. I lie in my warm womb, thinking about Holly the barmaid. I find I’ve forgotten Mariвngela’s face, if not other areas of her anatomy, but Holly’s face I remember in photographic detail. I should have asked Gьnter for her surname. A little later, the bells of Sainte-Agnиs’s church chime eight times. There were bells in my dream. My mouth is as dry as lunar dust and I drink the glass of water on the bedside table, pleased by the sight of the wedge of francs by the lamp—my winnings from last night’s pool session with Chetwynd-Pitt. Ha. He’ll be eager to win the money back, and an eager player is a sloppy player.

I pee in my garret’s minuscule en suite; hold my face in a sinkful of icy water for the count of ten; open the curtains and slatted shutters to let in the retina-drilling white light; hide last night’s winnings under a floorboard I loosened two visits ago; perform a hundred push-ups; put on the Turkish gown and venture down the steep wooden stairs to the first landing, holding the rope banister. Chetwynd-Pitt’s snoring in his room. The lower stairs take me to the sunken lounge, where I find Fitzsimmons and Quinn buried under tumuli of blankets on leather sofas. The VHS player has spat out The Wizard of Oz, but Pink Floyd’s Dark Side of the Moonis still playing on repeat. Hashish perfumes the air and last night’s embers glow in the fireplace. I tiptoe between two teams of Subbuteo soccer players, crunching crisps into the rug, and feed the fire a big log and crumbs of fire lighter. Tongues of flame lick and lap. A Dutch rifle from the Boer War hangs over the mantelpiece, whereon sits a silver-framed photograph of Chetwynd-Pitt’s father shaking hands with Henry Kissinger in Washington, circa 1984. I’m pouring myself a grapefruit juice in the kitchen when the phone there discreetly trills: “Good morning,” I say cutely. “Lord Chetwynd-Pitt the Younger’s residence.”

A male voice states, “Hugo Lamb. Got to be.”

I know this voice. “And you are?”

“Richard Cheeseman, from Humber, you dolt.”

“Bugger me. Not literally. How’s your earlobe?”

“Fine fine fine, but listen, I’ve got serious news. I met—”

“Hang on, where are you? Not Switzerland?”

“Sheffield, at my sister’s, but shut up and listen, this call’s costing me a bollock a minute. I was speaking with Dale Gow last night, and he told me that Jonny Penhaligon’s dead.”

I didn’t mishear. “ OurJonny Penhaligon? No fucking way.”

“Dale Gow heard from Cottia Benboe, who saw it on the local news, News South-West. Suicide. He drove off a cliff, near Truro. Fifty yards from the road, through a fence, three-hundred-foot drop onto rocks. I mean … he wouldn’t have suffered. Apart from whatever it was that drove him to do it, of course, and the … final drop.”

I could weep. All that money. Through the kitchen window I watch the snowplow crawl by. A well-timed young priest follows, his cheeks pink and breath white. “That’s … I don’t know what to say, Cheeseman. Tragic. Unbelievable. Jonny! Of all people …”

“Same here. Really. The lastperson you’d expect …”

“Did he … Was he driving his Aston Martin?”

A pause. “Yeah, he was. How did you know?”

Be more careful. “I didn’t, but that last night in Cambridge, at the Buried Bishop, he was saying how much he loved that car. When’s the funeral?”

“This afternoon. I can’t go—Felix Finch has got me tickets for an opera and I could never get to Cornwall in time—but maybe it’s for the best. Jonny’s family could do without an influx of strangers arriving at … at … wherever it is.”

“Tredavoe. Did Penhaligon leave a note?”

“Dale Gow didn’t mention one. Why?”

“Just thought it might shed a little light.”

“More details will emerge at the inquest, I suppose.”

Inquest? Details? Sweet shit. “Let’s hope so.”

“Tell Fitz and the others, will you?”

“God, yes. And thanks for phoning, Cheeseman.”

“Sorry for putting a downer on your holiday, but I thought you’d prefer to know. Happy New Year in advance.”

TWO P.M. THE passengers from the cable car pass through the waiting room of the Chemeville station, chattering in most of the major European languages, but she’s not among them, so I direct my mind back to The Art of War. My mind has ideas of its own, however, and directs itself towards a Cornish graveyard where the skin-sack of toxic waste recently known as Jonny Penhaligon is joining its ancestors in the muddy ground. Like as not it’s howling with rain, with an east wind clawing at the mourners’ umbrellas and dissolving the words of “For Those in Peril on the Sea” Xeroxed yesterday onto sheets of A4. Nothing throws the chasm between me and normals into starker relief than grief and bereavement. Even at the tender age of seven, I was embarrassed by—and for—my own family when our dog Twix died. Nigel wept himself sore, Alex was more upset than he had been the time his Sinclair ZX Spectrum arrived minus its transformer, and my parents were morose for days. Why? Twix was out of pain. We no longer had to endure the farts of a dog with colon cancer. Same story when my grandfather died: a tearing-out of hair, gnashing of teeth, revisionism about what a Messiah the tight-arsed old sod had been. Everyone said I’d handled myself manfully at his funeral, but if they could have read my mind, they would have called me a sociopath.

Here’s the truth: Who is spared love is spared grief.

GONE THREE P.M. Holly the barmaid sees me, frowns, and slows: a promising start. I close The Art of War. “Fancy meeting you here.”

Skiers stream by, behind her and between us. She looks around. “Where are your highly amusing friends?”

“Chetwynd-Pitt, which rhymes with Angel’s Tit, I notice—”

“As well as ‘piece of shit’ and ‘sexist git,’ Inotice.”

“I’ll file that away. Chetwynd-Pitt’s hungover, and the other two passed through about an hour ago, but I slipped on my ring of invisibility, knowing that my chances of sharing your ski lift up to the top”—I twirl my index finger towards Palanche de la Cretta’s summit—“would be a big fat zero if they were here too. I was embarrassed by Chetwynd-Pitt last night. He was crass. But I’m not.”

Holly considers this and shrugs. “None of it matters.”

“It does to me. I was hoping to go skiing with you.”

“And that’s why you’ve been sitting here since …”

“Since eleven-thirty. Three and a half hours. But don’t feel obligated.”

“I don’t. I just think you’re a bit of a plonker, Hugo Lamb.”

So my name has sunk in. “We’re all of us different things at different times. A plonker now, something nobler at other times. Don’t you agree?”

“Right now I’d describe you as a borderline stalker.”

“Tell me to sod off and off I will duly sod.”

“What girl could resist? Sod off.”

I do an urbane as-you-wish bow, stand, and slip The Art of Warinto my ski jacket. “Sorry for embarrassing you.” I head out.

“Oy.” It’s a lightening more than a softening. “Who says you’recapable of embarrassing me?”

I knock-knock my forehead. “Would ‘Sorry for finding you interesting’ go down any better?”

“A certain type of girl after a holiday romance would lap it up. Those of us who work here get a bit jaded.”

Machinery clanks and a big engine whines as the down-bound cable-car begins its journey. “I understand that you need armor, working in a bar where Europe’s Chetwynd-Pitts come to play. But jadedness runs through you, Holly, like a second nervous system.”

An incredulous little laugh. “You don’t know me.”

“ That’sthe weird part: I know I don’t know you. So how come I feel like I do?”

She does an exasperated grunt. “There’s rules … You don’t talk to someone you’ve known five minutes like you’ve known them for years. Bloody stop it.”

I hold up my palms. “Holly, if I am an arrogant twat, I’m a harmless arrogant twat.” I think of Penhaligon. “Virtually harmless. Look, would you let me share your ski lift up to the next station? It’s, what, seven, eight minutes? If I turn into a date from hell, it’ll soon be over—no no no, I know, nota date, it’s a shared ski chair. Then we’ll arrive and, with one expert thrust of your ski poles, I’m history. Please. Please?”

THE SKI LIFT guy clicks our rail into place, and I resist a joke about being swept off my feet as Holly and I are swept off our feet. December 30 has lost its earlier clarity and the summit of the Palanche de la Cretta is hidden in cloud. I follow the ski lift cable from pylon to pylon up the mountainside. The ravine opens up below us and, as I’m mugged by vertigo and grip the bar, my testicles run and hide next to my liver. Forcing myself to look down at the distant ground, I wonder about Penhaligon’s final seconds. Regret? Relief? Blank terror? Or did his head suddenly fill with “Babooshka” by Kate Bush? Two crows fly beneath our feet. They mate for life, my cousin Jason once told me. I ask Holly, “Do you ever have flying dreams?”

Holly looks dead ahead. Her goggles hide her eyes. “No.”

We’ve cleared the ravine again and pass sedately over a wide swath of the piste we’ll be skiing down later. Skiers curve, speed, and amble downhill to Chemeville station.

“Conditions look better after last night’s snow,” I say.

“Yeah. This mist’s getting thicker by the minute, though.”

That is true; the mountain peak is blurry and gray now. “Do you work at Sainte-Agnиs every winter?”

“What is this? A job interview?”

“No, but my telepathy’s a bit rusty.”

Holly explains: “I used to work at Mйribel over in the French Alps for a guy who knew Gьnter from his tennis days. When Gьnter needed a discreet employee, I got offered a transfer, a pay hike, and a ski pass.”

“Why ever would Gьnter need a discreet employee?”

“Not a clue—and, no, I don’t touch drugs. The world’s unstable enough without scrambling your brain for kicks.”

I think of Madam Constantin. “You’re not wrong.”

Empty ski chairs migrate from the mist ahead. Behind us, Chemeville is fading from view, and nobody’s following us up. “Wouldn’t it be freaky,” I think aloud, “if we saw the dead in the chairs opposite?”

Holly gives me a weird look. “Not dead as in undead, with bits dropping off,” I hear myself trying to explain. “Dead as in your own dead. People you knew, who mattered to you. Dogs, even.” Or Cornishmen.

The steel-tube-and-plastic chair squeaks. Holly’s chosen to ignore my frankly bizarre question, and to my surprise asks this: “Are you from one of those army-officer families?”

“God, no. My dad’s an accountant and Mum works at Richmond Theatre. Why do you ask?”

“ ’Cause you’re reading a book called The Art of War.”

“Oh, that. I’m reading Sun Tzu because it’s three thousand years old, and every CIA agent since Vietnam has studied it. Do you read?”

“My sister’s the big reader, really, and sends me books.”

“How often do you go back to England?”

“Not so often.” She fiddles with a Velcro glove strap. “I’m not one of those people who’ll spill their guts in the first ten minutes. Okay?”

“Okay. Don’t worry, that just means you’re sane.”

“I knowI’m sane, and I wasn’t worried.”

Awkward silence. Something makes me look over my shoulder; five ski chairs behind sits a solo passenger in a silver parka with a black hood. He sits with his arms folded, his skis making a casual X. I look ahead again, and try to think of something intelligent to say, but I seem to have left all my witty insights at the ski-lift station below.

AT THE PALANCHE de la Cretta station, Holly slides off the chairlift like a gymnast, and I slide off like a sack of hammers. The ski-lift guy greets Holly in French, and I slope off out of earshot. I find I’m waiting for the skier in the silver parka to appear from the fast-flowing mist; I count a twenty-second gap between each ski chair, so he’ll be here in a couple of minutes, at most. Odd thing is, he never arrives. With mild but rising alarm, I watch the fifth, sixth, seventh chairs after us arrive without a passenger … By the tenth, I’m worried—not so much that he’s fallen off the ski chair, but that he wasn’t there in the first place. The Yeti and Madam Constantin have shaken my faith in my own senses, and I don’t like it. Finally a pair of jolly bear-sized Americans appear, thumping to earth with gusts of laughter and needing the ski-lift guy’s help. I tell myself the skier behind us was a false memory. Or I dreamt him. Holly joins me at the lip of the run, marked by flags disappearing into cloud. In a perfect world, she’ll say, Look, why don’t we ski down together?“Okay,” she says, “this is where I say goodbye. Take care, stay between the poles, and no heroics.”

“Will do. Thanks for letting me hitch a ride up.”

She shrugs. “You must be disappointed.”

I lift my goggles so she can see my eyes, even if she won’t show me hers. “No. Not in the least. Thank you.” I’m wondering if she’d tell me her surname if I asked. I don’t even know that.

She looks downhill. “I must seem unfriendly.”

“Only guarded. Which is fair enough.”

“Sykes,” she says.

“I’m sorry?”

“Holly Sykes, if you were wondering.”

“It … suits you.”

Her goggles hide her face but I’m guessing she’s puzzled.

“I don’t quite know what I meant by that,” I admit.

She pushes off and is swallowed by the whiteness.

THE PALANCHE DE la Cretta’s middle flank isn’t a notorious descent, but stray more than a hundred meters off-piste to the right and you’ll need near-vertical skiing skills or a parachute, and the fog’s so dense that I take my own sweet time and stop every couple of minutes to wipe my goggles. About fifteen minutes down, a boulder shaped like a melting gnome rears from the freezing fog by the edge of the piste. I huddle in its leeward side to smoke a cigarette. It’s quiet. Very quiet. I consider how you don’t get to choose whom you’re attracted to, you only get to wonder about it, retrospectively. Racial differences I’ve always found to have an aphrodisiac effect on me, but class difference is sexuality’s Berlin Wall. Certainly, I can’t read Holly Sykes as well as I can girls from my own incometax tribe, but you never know. God made the whole Earth in six days, and I’m in Switzerland for nine or ten.