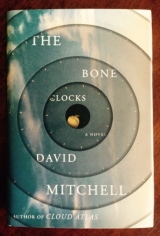

Текст книги "The Bone Clocks"

Автор книги: David Mitchell

Жанры:

Классическое фэнтези

,сообщить о нарушении

Текущая страница: 14 (всего у книги 40 страниц)

Aoife giggles in her sleep, then groans sharply.

I go over. “You okay, Aoife? It’s only a dream.”

Unconscious Aoife complains, “No, silly! The lemonone.” Then her eyes flip open like a doll’s in a horror movie: “We’re going to a hotel in Brighton later, ’cause Aunty Sharon’s marrying Uncle Pete, and we’ll meet you there, Daddy. I’m a bridesmaid.”

I try not to laugh, and stroke Aoife’s hair back from her face. “I know, love. We’re all here now, so you go back to sleep. I’ll be here in the morning and we’ll all have a brilliant day.”

“Good,” Aoife pronounces, teetering on the brink of sleep …

… she’s gone. I pull the duvet over her My Little Pony pajama top and kiss her forehead, remembering the week in 1997 when Holly and I made this precious no-longer-quite-so-little life-form. The Hale-Bopp Comet was adorning the night sky, and thirty-nine members of the Heaven’s Gate cult committed mass suicide in San Diego so their souls could be picked up by a UFO in the comet’s tail and be transported to a higher state of consciousness beyond human. I rented a cottage in Northumbria and we had plans to go hiking along Hadrian’s Wall, but hiking didn’t turn out to be the principal activity of the week. Now look at her. I wonder how she sees me. A bristly giant who teleports into her life and teleports out again for mystifying reasons, perhaps—not so different from how I saw my own father, I guess, except while I’m away on various assignments, Dad went away to various prisons. I’d love to know how Dad saw me when I was a kid. I’d love to know a hundred things. When a parent dies, a filing cabinet full of all the fascinating stuff also ceases to exist. I never imagined how hungry I’d be one day to look inside it.

When I was back in February she was having her period.

I hear Holly’s key in the door. I feel vaguely guilty.

Not half as guilty as she’ll make me feel, though.

Holly’s having trouble with the lock so I go over, put the chain on, and open it up a crack. “Sorry, sweetheart,” I tell her, in my Michael Caine voice. “I never ordered no kinky massage. Try next door.”

“Let me in,” says Holly, sweetly, “or I’ll kick you in the nuts.”

“Nope, I didn’t order no kick in the nuts, neither. Try—”

Not so sweetly: “Brubeck, I need to use the loo!”

“Oh, all right, then.” I unchain the door and stand aside. “Even if you have come home too plastered to use a key, you dirty stop out.”

“The locks in this hotel are all fancy and burglar-proofed. You need a PhD to open the damn things.” Holly bustles past to the bathroom, peering down at Aoife in passing. “Plus I only had a fewglasses of wine. Mam was there as well, remember.”

“Right, as if Kath Sykes was ever a girl to put the dampeners on a ‘wine-tasting session.’ ”

Holly closes the bathroom door. “Was Aoife okay?”

“She woke up for a second, otherwise not a squeak.”

“Good. She was soexcited on the train down, I was afraid she was going to be up all night dancing on the ceiling.” Holly flushes the toilet to provide a bit of noise cover. I go over to the window again. The funfair at the end of the pier is winding down, by the look of it. Such a lovely night. My proposed six-month extension for Spyglassin Iraq is going to wreck it, I know. Holly opens the bathroom door, smiling at me and drying her hands. “How did you spend your quiet night in? Snoozing, writing?”

Her hair’s up, she’s wearing a low-cut figure-hugging black dress and a necklace of black and blue stones. She hardly ever looks like that anymore. “Thinking impure thoughts about my favorite yummy mummy. Can I help you out of that dress, Miss Sykes?”

“Down, boy.” She fusses over Aoife. “We’re sharing a room with our daughter, you might have noticed.”

I walk over. “I can operate on silent mode.”

“Not tonight, Romeo. I’m having my period.”

Thing is, I haven’t been back often enough in the last six months to know when Holly’s period is. “Guess I’ll have to make do with a long, slow snog, then.”

“ ’Fraid so matey.” We kiss, but it’s not as long and slow as advertised, and Holly isn’t as drunk as I was half hoping. When was it that Holly stopped opening her mouth when we kiss? It’s like kissing a zipped-up zip. I think of Big Mac’s aphorism: In order to have sex, women need to feel loved; but in order for men to feel loved, we need to have sex. I’m keeping my half of the deal—so far as I know—but sexually, Holly acts like she’s forty-five or fifty-five, not thirty-five. Of course I’m not allowed to complain, because that’s pressurizing her. Once Holly and I could talk about anything, anything, but all these no-go areas keep springing up. It all makes me … I’m not allowed to be sad either, because then I’m a sulky boy who isn’t getting the bag of sweets he thinks he deserves. I haven’t cheated on her—ever—not that Baghdad is a hotbed of sexual opportunity, but it’s depressing still being a fully functioning thirty-five-year-old male and having to take matters into my own hands so often. The Danish photojournalist in Tajikistan last year would’ve been up for it if I’d been less anxious about how I’d feel when the taxi dropped me off at Stoke Newington and I heard Aoife yelling, “It’s Daaaaddyyy!”

Holly turns back to the bathroom. She leaves the door open, and starts to remove her makeup. “So, are you going to tell me or not?”

I sit on the edge of the double bed, alert. “Tell you what?”

She dabs cotton wool under her eyes. “I don’t know yet.”

“What makes you think I … have anything to tell you?”

“Dunno, Brubeck. Must be my feminine intuition.”

I don’t believe in psychics but Holly can do a good impression of one. “Olive asked me to stay on in Baghdad until December.”

Holly freezes for a few seconds, drops the cotton wool, and turns to me. “But you’ve already told her you’re quitting in June.”

“Yeah. I did. But she’s asking me to reconsider.”

“But you told meyou’re quitting in June. Me and Aoife.”

“I told her I’d call back on Monday. After discussing it with you.”

Holly’s looking betrayed. Or as if she’s caught me downloading porn. “We a greed, Brubeck. This would be your final final extension.”

“I’m only talking about another six months.”

“Oh, f’Chrissakes. You said that the lasttime.”

“Sure, but since I won the Sheehan-Dower Prize I’ve been—”

“ Andthe time before that. ‘Half a year, then I’m out.’ ”

“This’ll cover a year of Aoife’s college expenses, Hol.”

“She’d rather have a living father than a smaller loan.”

“That’s just”—you can’t call angry women “hysterical” these days; it’s sexist—“hyperbole. Don’t stoop to that.”

“Is that what Daniel Pearl said to his partner before he jetted off to Pakistan? ‘That’s just hyperbole’?”

“That’s tasteless. And wrongheaded. And Pakistan’s not Iraq.”

She lowers the toilet lid and sits on it so we’re roughly at eye level. “I’m sickof wanting to puke with fear every time I hear the word ‘Iraq’ or ‘Baghdad’ on the radio. I’m sickof hardly sleeping. I’m sickof having to hide from Aoife how worried I am. Fantastic, you’re an in-demand award-winning journalist, but you have a six-year-old who wants help riding a bike with no stabilizers. Being a crackly voice for a minute every two or three days, ifthe satphone’s working, isn’t enough. You area war junkie. Brendan was right.”

“No, I am not. I am a journalist doing what I do. Just as he does what he does and you do what you do.”

Holly rubs her head like I’m giving her a headache. “Go, then! Back to Baghdad, to the bombs taking the front off your hotel. Pack. Go. Back to ‘what you do.’ If it’s more precious than us. Only you’d better get the tenants out of your King’s Cross flat ’cause the next time you’re back in London, you’ll be needing somewhere to live.”

I keep my voice low: “Will you pleasefucking listento yourself?”

“No, youfucking listen to yourfuckingself! Last month you agree to quit in June and come home. Your high-powered American editor says, ‘Make it December.’ You say, ‘Uh, okay.’ Then you tell me. Who are you with, Brubeck? Me and Aoife, or Olive Sun and Spyglass?”

“I’m being offered another six months’ work. That’s all.”

“No, it’s not‘all’ ’cause after Fallujah dies down or gets bombed to shit it’ll be Baghdad or Afghanistan Part Two or someplace else, there’s alwayssomeplace else, and on and on until the day your luck runs out and then I’m a widow and Aoife has no dad. Yes, I put up with Sierra Leone, yes, I survived your assignment in Somalia, but Aoife’s older now. She needs a dad.”

“Suppose I told you, ‘No, Holly, you can’t help homeless people anymore. Some have AIDS, some have knives, some are psychotic. Quit that job and work for … for Greenland supermarkets instead. Put all those people skills of yours to use on dried goods. In fact, I’m orderingyou to, or I’ll kick you out.’ How would yourespond?”

“F’Chrissakes, the risks are different.” Holly lets out an angry sigh. “Why bring this up in the middle of the bloody night? I’m Sharon’s matron of honor tomorrow. I’ll look like a hungover panda. You’re at a crossroads, Brubeck. Choose.”

I make an ill-advised quip: “More of a T-junction, technically.”

“Right. I’d forgotten. It’s all a joke to you, isn’t it?”

“Oh, Holly, for God’s sake, that’s not what I—”

“Well, I’m notjoking. Quit Spyglassor move out. My house isn’t just a storage dump for your dead laptops.”

THREE O’CLOCK IN the morning, and things are fairly shit. “Never let the sun set on an argument,” my uncle Norm used to say, but my uncle Norm didn’t have a kid with a woman like Holly. I said “Good night” to her peaceably enough after switching off the lights, but her “Good night” back sounded very like “Screw you,” and she turned away. Her back’s as inviting as the North Korean border. It’s six o’clock in the morning in Baghdad now. The stars will be fading in the freeze-dried dawn, as skin-and-bone dogs pick through rubble for something to eat, the mosques’ Tannoys summon the devout, and bundles by the side of the road solidify into last night’s crop of dead bodies. The luckier corpses have a single bullet through the head. At the Safir Hotel, repairs will be under way. Daylight will be reclaiming my room at the back, 555. My bed will be occupied by Andy Rodriguez from The Economist—I owe him a favor from the fall of Kabul two years ago—but everything else should be the same. Above the desk is a map of Baghdad. No-go areas are marked in pink highlighter. After the invasion last March, the map was marked by only a few pink slashes here and there: Highway 8 south to Hillah, and Highway 10 west to Fallujah—other than that, you could drive pretty much wherever you wanted. But as the insurgency heated up the pink ink crept up the roads north to Tikrit and Mosul, where an American TV crew got shot to shit. Ditto the road to the airport. When Sadr City, the eastern third of Baghdad, got blocked off, the map became about three-quarters pink. Big Mac says I’m re-creating an old map of the British Empire. This makes the pursuit of journalism difficult in the extreme. I can no longer venture out to the suburbs to get stories, approach eyewitnesses, speak English on the streets, or even, really, leave the hotel. Since the new year my work for Spyglasshas been journalism by proxy, really. Without Nasser and Aziz I’d have been reduced to parroting the Panglossian platitudes tossed to the press pack in the Green Zone. All of which begs the question, if journalism is so difficult in Iraq, why am I so anxious to hurry back to Baghdad and get to work?

Because it is difficult, but I’m one of the best.

Because only the best canwork in Iraq right now.

Because if I don’t, two good men died for nothing.

April 17

WINDSURFERS, SEAGULLS, AND SUN, a salt-’n’-vinegar breeze, a glossy sea, and an early walk along the pier with Aoife. Aoife’s never been on a pier before and she loves it. She does a row of froggy jumps, enjoying the flicker of the LED bulbs in the heels of her trainers. We’d have killed for shoes like that when I was a kid, but Holly says it’s hard to find shoes that don’tlight up these days. Aoife has a Dora the Explorer helium balloon tied to her wrist. I just paid a fiver for it to a charming Pole. I look behind us, trying to work out which window of the Grand Maritime Hotel is our room. I invited Holly out on the walk but she said she had to help Sharon get ready for a hairdresser who isn’t due until nine-thirty. It’s not yet eight-thirty. It’s her way of letting me know she hasn’t shifted her position from last night.

“Daddy? Daddy? Did you hear me?”

“Sorry, poppet,” I tell Aoife. “I was miles away.”

“No, you weren’t. You’re right here.”

“I was miles away metaphorically.”

“What’s meta … frickilly?”

“The opposite of literally.”

“What’s litter-lily?”

“The opposite of metaphorically.”

Aoife pouts. “Be serious, Daddy.”

“I’m always serious. What were you asking, poppet?”

“If you were any animal, what would you be? I’d be a white Pegasus with a black star on its forehead, and my name’d be Diamond Swiftwing. Then Mummy and me could fly to Bad Dad and see you. And Pegasuses don’t hurt the planet like airplanes—they only poo. Grandpa Dave says when he was small hisdaddy used to hang apples on very tall poles over his allotment, so all the Pegasuses’d hover there, eat, and poo. Pegasus poo is so magic the pumpkins’d grow really really big, bigger than me, even, so just one would feed a family for a week.”

“Sounds like Grandpa Dave. Who’s the Bad Dad?”

Aoife frowns at me. “The place where youlive, silly.”

“Baghdad. ‘ Bagh-dad.’ But I don’t live there.” God, it’s lucky Holly didn’t hear that. “It’s just where I work.” I imagine a Pegasus over the Green Zone, and see a bullet-riddled corpse plummeting to earth and getting barbecued by Young Republicans. “But I won’t be there forever.”

“Mummy wants to be a dolphin,” says Aoife, “because they swim, talk a lot, smile, and they’re loyal. Uncle Brendan wants to be a Komodo dragon, ’cause there’re people on Gravesend Council he’d like to bite and shake to pieces, which is how Komodo dragons make their food smaller. Aunty Sharon wants to be an owl because owls are wise, and Aunt Ruth wants to be a sea otter so she can spend all day floating on her back in California and meet David Attenborough.” We reach a section of the pier where it widens out around an amusement arcade. Big letters spelling BRIGHTON PIER stand erect between two limp Union flags. The arcade’s not open yet, so we follow the walkway around the outside of the arcade. “What animal would you be, Daddy?”

Mum used to call me a gannet; and as a journalist I’ve been called a vulture, a dung beetle, a shit snake; a girl I once knew called me her dog, but not in a social context. “A mole.”

“Why?”

“They’re good at burrowing into dark places.”

“Why d’you want to burrow into dark places?”

“To discover things. But moles are good at something else, too.” My hand rises like a possessed claw. “Tickling.”

But Aoife tilts her head to one side like a scale model of Holly. “If you tickle me I’ll wet myself and then you’ll have to wash my pants.”

“Okay.” I act contrite. “Moles don’t tickle.”

“I should think so too.” How she says that makes me afraid Aoife’s childhood’s a book I’m flicking through instead of reading properly.

Behind the arcade, seagulls are squabbling over chips spilling from a ripped-open bag. Big bastards, these birds. A row of stalls, booths, and shops runs down the middle of the pier. I can’t help but notice the woman walking towards us, because everything around her shifts out of focus. She’s around my age, give or take, and tall for a woman though not stand-outishly so. Her hair is white-gold in the sun, her velvet suit is the dark green of moss on graves, and her bottle-blue sunglasses will be fashionable some decades from now. I put on my own sunglasses. She compels attention. She compels. She’s way out of my class, she’s way out of anybody’s class, and I feel grubby and disloyal to Holly, but look at her, Jesus Christ, lookat her—graceful, lithe, knowing, and light bends around her. “Edmund Brubeck,” say her wine-red lips. “As I live and breathe, it’s you, isn’t it?”

I’ve stopped in my tracks. You don’t forget beauty like this. How on earth does she know me, and why don’t I remember? I take off my sunglasses now and say, “Hi!,” hoping that I sound confident, hoping to buy time for clues to emerge. Not a native English accent. European. French? Bendier than German, but not Italian. No journalist looks this semidivine. An actress or model I interviewed, years ago? Someone’s trophy wife from a more recent party? A friend of Sharon’s in Brighton for the wedding? God, this is embarrassing.

She’s still smiling. “I have you at a disadvantage, don’t I?”

Am I blushing? “You have to forgive me, I—I’m …”

“I’m Immaculйe Constantin, a friend of Holly’s.”

“Oh,” I bluster, “Immaculйe—yes, of course!” Do I half-know that name from somewhere? I shake her hand and perform an awkward cheek-to-cheek kiss. Her skin’s as smooth as marble but cooler than sun-warmed skin. “Forgive me, I … I just got back from Iraq yesterday and my brain’s frazzled.”

“There’s nothing to forgive,” says Immaculйe Constantin, whoever the hell she is. “So many faces, so many faces. One must lose a few old ones to make space for the new. I knew Holly as a girl in Gravesend, although I left town when she was eight years old. It’s curious how the two of us keep bumping into each other, every now and then. As if the universe long ago decided we’re connected. And thisyoung lady,” she gets down on one knee to look eye-to-eye at my daughter, “must be Aoife. Am I correct?”

Wide-eyed Aoife nods. Dora the Explorer sways and turns.

“And how old are you now, Aoife Brubeck? Seven? Eight?”

“I’m six,” says Aoife. “My birthday’s on December the first.”

“How grown up you look! December the first? My, my.” Immaculйe Constantin recites in a secretive, musical voice: “ ‘A cold coming we had of it, just the worst time of the year for a journey, and such a journey: the ways deep and the weather sharp, the very dead of winter.’ ”

Holidaymakers pass us by like they’re ghosts, or we are.

Aoife says, “There’s not a cloud in the sky today.”

Immaculйe Constantin stares at her. “How right you are, Aoife Brubeck. Tell me. Do you take after your mummy most, do you think, or your daddy?”

Aoife sucks in her lip and looks up at me.

Waves slap and echo below us and a Dire Straits song snakes over from the arcade. “Tunnel of Love” it’s called; I loved it when I was a kid. “Well, I like purple best,” says Aoife, “and Mummy likes purple. But Daddy reads magazines all the time, whenever he’s home, and I read a lot too. Specially I Love Animals. If you could be any animal, what would you be?”

“A phoenix,” murmurs Immaculйe Constantin. “Or thephoenix, in truth. How about an invisible eye, Aoife Brubeck? Do you have one of those? Would you let me check?”

“Mummy has blue eyes,” says Aoife, “but Daddy’s are chestnut brown and mine are chestnut brown, too.”

“Oh, not thoseeyes”—now the woman removes her strange blue sunglasses. “I mean your special, invisible eye, just … here.” She rests her fingers on Aoife’s right temple and strokes her forehead with her thumb, and deep in my liver or somewhere I know something’s weird, something’s wrong, but it’s drowned out when Immaculйe Constantin smiles up at me with her heart-walloping beauty. She studies a space above my eyes, then turns back to Aoife’s, and frowns. “No,” she says, and purses her painterly lips. “A pity. Your uncle’s invisible eye was magnificent, and your mother’s was enchanting, too, before it was sealed shut by a wicked magician.”

“What’s an invisible eye?” asks Aoife.

“Oh, that hardly matters.” She stands up.

I ask, “Are you here for Sharon’s wedding?”

She replaces her sunglasses. “I’m finished here.”

“But … You’re a friend of Holly’s, right? Aren’t you even going to …” But as I look at her, I forget whatever it was I meant to ask.

“Have a heavenly day.” She walks towards the arcade.

Aoife and I watch her shrink as she moves further away.

My daughter asks, “Who was that lady, Daddy?”

SO I ASK my daughter, “Who was what lady, darling?”

Aoife blinks up at me. “What lady, Daddy?”

We look at each other, and I’ve forgotten something.

Wallet, phone; Aoife; Sharon’s wedding; Brighton Pier.

Nope. I haven’t forgotten anything. We walk on.

A boy and girl are snogging, like the rest of the world doesn’t exist. “That’s gross!” declares Aoife, and they hear, and glance down, before resuming their tonsil-tickling. Yeah, I tell the boy telepathically, enjoy the cherries and cream because twenty years on from now nothing tastes as good. He ignores me. Up ahead, a picture spray-painted on a rolled-down metal shutter captures Aoife’s attention: a Merlinesque face with a white beard and spiral eyes in a halo of Tarot cards, crystals, and stardust. Aoife reads the name: “D-wiggert?”

“Dwight.”

“ ‘Dwight … Silverwind. For-tune … Teller.’ What’s that?”

“Someone who claims to be able to read the future.”

“ Class!Let’s go inside and see him, Daddy.”

“Why would you want to see a fortune-teller?”

“To know if I’ll open my animal-rescue center.”

“What happened to being a dancer like Angelina Ballerina?”

“That was agesago, Daddy, when I was little.”

“Oh. Well, no. We won’t be visiting Mr. Silverwind.”

One, two, three—and here’s the Sykes scowl: “Why not?”

“First, he’s closed. Second, I’m sorry to say that fortune-tellers can’t really tell the future. They just fib about it. They—”

The shutter is rattled up by a less flattering version of the Merlin on the shutter. This Merlin looks shat out by a hippo, and is dressed up in prog-rock chic: a lilac shirt, red jeans, and a waistcoat encrusted with gems as fake as its wearer.

Aoife, however, is awestruck. “Mr. Silverwind?”

He frowns and looks around before looking down. “I am he. And you are who, young lady?”

A Yank. Of bloody course. “Aoife Brubeck,” says Aoife.

“Aoife Brubeck. You’re up and about very early.”

“It’s my aunty Sharon’s wedding today. I’m a bridesmaid.”

“May you have an altogether sublime day. And this gentleman would be your father, I presume?”

“Yes,” says Aoife. “He’s a reporter in Bad Dad.”

“I’m sure Daddy tries to be good, Aoife Brubeck.”

“She means Baghdad,” I tell the joker.

“Then Daddy must be very … brave.” He looks at me. I stare back. I don’t like his way of talking and I don’t like him.

Aoife asks, “Can you reallysee the future, Mr. Silverwind?”

“I wouldn’t be much of a fortune-teller if I couldn’t.”

“Can you tell myfuture? Please?”

Enough of this. “Mr. Silverwind is busy, Aoife.”

“No, he isn’t, Daddy. He hasn’t got one customer even!”

“I usually ask for a donation of ten pounds for a reading,” says the old fraud, “but, off-peak, to specialyoung ladies, five would suffice. Or”—Dwight Silverwind reaches to a shelf behind him and produces a pair of books—“Daddy could purchase one of my books, either The Infinite Tetheror Today Will Happen Only Oncefor the special rate of fifteen pounds each, or twenty pounds for both, and receive a complimentary reading.”

Daddy would like to kick Mr. Silverwind in his crystal balls. “We’ll pass on your generosity,” I tell him. “Thanks.”

“I’m open until sunset, if you change your mind.”

I tug at my daughter’s hand to tell her we’re moving on, but she flares up: “It’s not fair, Daddy! I want to know my future!”

Just bloody great. If I take back a tearful Aoife, Holly’ll be insufferable. “Come on—Aunty Sharon’s hairdresser will be waiting.”

“Oh dear.” Silverwind retreats into his booth. “I foresee trouble.” He shuts a door marked THE SANCTUM behind him.

“ Nobody knows the future, Aoife. These”—I aim this at the Sanctum—“ liarstell you whatever they think you want to hear.”

Aoife turns darker, redder, and shakier. “No!”

My own temper now wakes up. “No what?”

“No no no no no no no no no no.”

“Aoife! Nobody knows the future. That’s why it’s the future!”

My daughter turns red, shaky, and screeches: “Kurde!”

I’m about to flame her for bad language—but did my daughter just call me a Kurd? “What?”

“Aggie says it when she’s cross but Aggie’s a milliontimes nicer than youand at least she’s there! You’re never even home!” She storms off back down the pier on her own. Okay, a mild Polish swearword, a mature dollop of emotional blackmail, picked up perhaps from Holly. I follow. “Aoife! Come back!”

Aoife turns, tugs the balloon string off and threatens to let it go.

“Go ahead.” I know how to handle Aoife. “But be warned, if you let go, I’ll neverbuy you a balloon again.”

Aoife twists her face up into a goblin’s and—to my surprise, and hurt—lets the balloon go. Off it flies, silver against blue, while Aoife dissolves into cascading sobs. “I hateyou—I hateDora the Explorer—I wish you were back—back in Bad Dad—forever and ever! I hateyou I hateyou I hateyou I hate your guts!”

Then Aoife’s eyes shut tight and her six-year-old lungs fill up.

Half of Sussex hears her shaken, sobbing scream.

Get me out of here. Anywhere.

Anywhere’s fine.

NASSER DROPPED ME near the Assassin’s Gate, but not too near; you never know who’s watching who’s giving lifts to foreigners, and the guards at the gate have the jumpiest trigger fingers, the poor bastards. “I’ll call you after the press conference,” I told Nasser, “or if the network’s down, just meet me here at eleven-thirty.”

“Perfect, Ed,” replied my fixer. “I get Aziz. Tell Klimt, all Iraqis love him. Seriously. We build big statue with big fat cock pointing to Washington.” I slapped the roof and Nasser drove off. Then I walked the fifty meters to the gate, past the lumps of concrete placed in a slalom arrangement, past the crater from January’s bomb, still visible; half a ton of plastic explosives, topped with a smattering of artillery shells, killing twenty and maiming sixty. Olive used five of Aziz’s photos, and the Washington Postpaid him a reprint fee.

The queue for the Assassin’s Gate wasn’t too bad last Saturday; about fifty Iraqi staffers, ancillary workers, and preinvasion residents of the Green Zone were ahead of me, lining up to one side of the garish arch, topped by a large sandstone breast with an aroused nipple. An East Asian guy was ahead of me, so I struck up a conversation. Mr. Li, thirty-eight, was running one of the Chinese restaurants inside the zone—no Iraqi is allowed near the kitchens for fear of a mass poisoning. Li was returning from a meeting with a rice wholesaler, but when he found out my trade his English mysteriously worsened and my hopes for a “From Kowloon to Baghdad” story evaporated. So I turned my thoughts to the logistics of the day ahead until it was my turn to be ushered into the tunnel of dusty canvas and razor wire. “Blast Zone” security has been neo-liberalized, and the affable ex-Gurkhas who used to man Checkpoint One have been undercut by an agency recruiting Peruvian ex-cops, who are willing to risk their lives for four hundred dollars a month. I showed my press ID and British passport, got patted down, and had my two Dictaphones inspected by a captain with an epidermal complaint who left flakes of his skin on them.

Repeat the above three times at Checkpoints Two through Four and you find yourself inside the Emerald City—as the Green Zone has inevitably come to be known, a ten-square-kilometer fortress maintained by the U.S. Army and its contractors to keep out the reality of postinvasion Iraq and preserve the illusion of a kind of Tampa, Florida, in the Middle East. Barring the odd mortar round, the illusion is maintained, albeit it at a galactic cost to the U.S. taxpayer. Black GM Suburbans cruise at the thirty-five miles per hour speed limit on the smooth roads; electricity and gasoline flow 24/7; ice-cold Bud is served by bartenders from Mumbai who rename themselves Sam, Scooter, and Moe for the benefit of their clientele; the Filipino-run supermarket sells Mountain Dew, Skittles, and Cheetos.

The spotless hop-on, hop-off circuit bus was waiting at the Assassin’s Gate stop. I hopped on, relishing the air-conned air, and the bus pulled off at the very second the timetable promised. The smooth ride down Haifa Street passes much of the best real estate in the nation and the Ziggurat celebrating Iraq’s bloody stalemate against Iran—one of the ugliest memorials on Earth—and several large areas of white Halliburton trailers. Most of the CPA’s staff live in these trailer parks, eat in the chow halls, shit in portable cubicles, never set foot outside the Green Zone, and count the days until they can go home and put down a deposit on a real house in a nice neighborhood.

When I got off the bus at the Republican Palace, about twenty joggers came pounding down the sidewalk, all wearing wraparound sunglasses, holsters, and sweat-blotted T-shirts. Some of the T-shirts were emblazoned with the quip WHO’S YOUR BAGHDADDY NOW?; the remainder declared, BUSH-CHENEY 2004. To avoid a collision I had to jump out of their way. They sure as hell weren’t going to get out of mine.

· · ·

I STEP ASIDE for a stream of flouncy-frocked girls who run giggling down the aisle of All Saints’ Church in Hove, Brighton’s genteel twin. “Half the florists in Brighton’ll be jetting off to the Seychelles on the back of this,” remarks Brendan. “Kew bloody Gardens, or what?”

“A lot of work’s gone into it, for sure.” I gaze at the barricade of lilies, orchids, and sprays of purples and pinks.

“A lot of doshhas gone into it, our Ed. I asked Dad how much all this set him back, but he says it’s all …” he nods across the aisle to the Webbers’ side of the church and mouths taken care of. Brendan checks his phone. “He can wait. Speaking of dosh, I meant to ask before you fly back to your war zone about your intentions regarding the elder of my sisters.”

Did I hear that right? “You what?”

Brendan grins. “Don’t worry, it’s a bit late to make an honorable woman out of our Hol now. Property, I’m talking. Her pad up in Stoke Newington’s cozy, like a cupboard under the stairs is cozy. You’ll have your sights set a bit higher up the property ladder, I trust?”

As of right now, Holly’s sights are set on kicking me out on my arse. “Eventually, yes.”