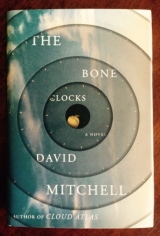

Текст книги "The Bone Clocks"

Автор книги: David Mitchell

Жанры:

Классическое фэнтези

,сообщить о нарушении

Текущая страница: 28 (всего у книги 40 страниц)

In most other subject areas, however, Esther was the teacher. Her metaage became apparent one night when she recited the names of all her previous hosts, and I lined up one pebble per name. There were 207 pebbles. Moombaki sojourned into new hosts when they were about ten and stayed until death, which implied a metalife stretching back approximately seven millennia. This was twice as old as Xi Lo, the oldest Atemporal known to Horology, who at twenty-five centuries was a stripling compared to Esther, whose soul predated Rome, Troy, Egypt, Peking, Nineveh, and Ur. She taught me some of her invocations, and I identified within them various tributaries to the Deep Stream from long before the Schism. On some nights we transversed together, and Esther enfolded my soul in hers so I could spirit-walk much further and faster than I was otherwise able. When she scansioned me I felt like a third-rate poet showing his doggerel to a Shakespeare. When I scansioned her, I felt like a minnow tipped from a jar into a deep inland sea.

TWENTY DAYS AFTER my arrival, I said my goodbyes and set out with Esther toward the Swan River valley accompanied by the four warriors who had escorted us from Jervoise Bay. We headed north from Five Fingers, climbing into the Perth Hills. My guides knew the wooded, trackless slopes as unerringly as Pablo Antay knew the thoroughfares and alleys of Buenos Aires. We camped in a dry creek near a water hole, and after a supper of yam, berries, and duck meat, Pablo Antay fell into steep-sided, slippery sleep. I slept until Esther subwoke me, which is a disorienting reveille. It was still dark, but a predawn wind was stirring the slanting trees into near speech. Esther was outlined against a banksia bush. Blearily, I subasked, All well?

Esther subreplied, Follow. We walked through a stretch of nighttime forest of rustling she-oaks, up a sandstone ridge that cleared the treeline before trifurcating into three “prongs.” Each of these ridges was only a few feet wide, but a hundred paces long, and with steep drops on either side I proceeded with great caution. Esther told me this place was called, descriptively, Emu’s Claw, and led me along the central “toe.” It ended at a lookout point over the Swan River. The looping watercourse was burnished pewter by starlight, and the land was a crumpled patchwork of light and dark blacks. A day’s walk to the west, streaks of surf delineated the ocean, and I guessed that a rough clutter on the north bank of the river was Perth.

Esther sat, so I sat too. A currawong sang throaty gargle phrases in a peppermint tree. I’m gunna teach y’m’true name.

You told me, I subreplied, it would take a day to learn.

Aye, it’s true, but I’m gunna speak it inside y’head, Marinus.

I hesitated. This is a gift I’ll struggle to repay. My true name is only one word long, and you already know that.

“Ain’t y’fault yurra savage,” she said. “Shurrup now. Open up.”

Esther’s soul ingressed and inscribed her long, long, true name onto my memory. Moombaki’s name had grown with the tens, hundreds, and thousands of years since Moombaki’s mother-birth at the Five Fingers, back when it was known as Two Hands. While much of her true name lay beyond my knowledge of the Noongar language, as the minutes passed I understood that her name was also a history of her people, a sort of Bayeux Tapestry that bound myth with loves, births, deaths; hunts, battles, journeys; droughts, fires, storms; and the names of every host within whose body Moombaki had sojourned. With the word Estherher name ended. My visitor egressed and I opened my eyes to find slanted sunlight flaming the canopy below us sharp green, torching the scrub dark gold and reddening the whale-rib clouds, and countless thousands of birds, singing, shrieking, yammering. “Not a bad name,” I said, already feeling the ache of loss.

A marri tree bled gum and starry blooms. Corymbia calophylla.

“Come back anytime,” she said, “or y’kin y’spoke of.”

“I will,” I promised, “but my face will have changed.”

“World’s changin’,” she said. “Even here. Can’t stop it.”

“How’ll we find you, Esther? Me, or Xi Lo, or Holokai?”

Camp here. This place. Emu’s Claw. I’ll know. The Land’ll tell.

I wasn’t surprised to find that she’d gone back. So I set off for Perth, where a dishonorable man called Caleb Warren would soon suffer the fright of his life.

I FINISH FILLING in twenty-seven across—VERTIGO—before looking up to find Iris Marinus-Fenby mirrored in Holly Sykes’s sunglasses. Today’s head-wrap is lilac. I guess her hair only partly recovered from the chemo five years ago. Holly’s indigo dress extends from the buttoned throat to her ankles. “I’m a world-class ignorer of attention-seekers,” Holly slaps the envelope on the table, “but this is so crass, so intrusive, so bizarre, it’s off the scale. So you win. I’m here. I walked down Broadway, and at every crossing I thought, Why give even one minute to this head-meddling nutso?I don’t know how often I almost turned back.”

I ask, “Why didn’t you?”

“ ’Cause I need to know: If Hugo Lamb wishes to contact me, why not do it like everyone else and send an email via my agent? Why send youand this”—she knocks on the envelope—“this tampered-with photo? Does he think it’ll impress me? Reignite old flames? ’Cause if he does he’s in for a heck of a disappointment.”

“Why not sit down and order lunch while I explain?”

“I don’t think so. I only eat lunch with friends.”

“Coffee, then? One drinks coffee with anyone.”

With ill grace, Holly accedes. I mime a cup and mouth “Coffee” at Nestor, who makes a coming-right-up face. “First,” I tell Holly, “Hugo Lamb knows nothing about this. We hope. He’s gone by the name of Marcus Anyder for many years, incidentally.”

“So if Hugo Lamb hasn’t sent you, how can you possibly know that we met years ago in an obscure Swiss ski resort?”

“One of us resides in the Dark Internet. Overhearing things is what he does for a living, as it were.”

“And you. Are you still a Chinese doctor who died in 1984? Or are you alive and female today?”

“I am all those four.” I put a business card on the table. “Dr. Iris Marinus-Fenby. A clinical psychiatrist based in Toronto, though I consult further afield. And, yes, until 1984 I was Yu Leon Marinus.”

Holly removes her sunglasses, scrutinizes the card, and me, with distaste. “I see I have to spell this out, so here goes: I haven’t seen Hugo Lamb since New Year’s Day 1992, when he was in his early twenties, yeah? He’ll be in his midfifties by now. Like me. Now, the manipulator of this image shows Hugo Lamb stilllooking twenty-five years old, give or take, with the Helix Towers—built in 2018—and iShades hooked over his Qatar 2022 World Cup T-shirt. And the car. Cars didn’t look like that in the nineties. I was there. This photo has been buggered about with. Two questions for you: ‘Why bother?’ and ‘Who bothered?’ ”

A kid at the next table’s playing a 3D app: A kangaroo’s bouncing up a scrolling series of platforms. It’s off-putting. “The photo was taken last July,” I tell Holly. “It has not been altered.”

“So … Hugo Lamb found the fountain of eternal youth?”

A young waiter with Nestor’s heavyweight nose walks by with a T-bone steak sizzling on a hot plate. “Not a fountain, no. A place and a process. Hugo Lamb became an Anchorite of the Chapel of the Blind Cathar in 1992. Since his induction, he hasn’t aged.”

Holly takes this in and puffs out her cheeks. “Well, great. That’s that cleared up. My one-night fling is now … let’s say it, ‘immortal.’ ”

“Immortal with terms and conditions,” I equivocate. “Immortal only in the sense that he doesn’t age.”

Holly’s exasperated. “And nobody’s noticed, of course. Or does his family put it down to moisturizer and quinoa salad?”

“His family believe he drowned in a scuba-diving accident off Rabaul, near New Guinea, in 1996. Go ahead, call them.” I give Holly a card with the Lambs’ London number on it. “Or just shirabu one of his brothers, Alex or Nigel, and ask them.”

Holly stares. “Hugo Lamb faked his own death?”

I sip my tap water. It’s passed through many kidneys. “His new Anchorite friends arranged it. Obtaining a death certificate without a dead body is irksome, but they have years of experience.”

“Stop talking as if I believe you. Anyway, ‘Anchorites’? That’s something … medieval, isn’t it?”

I nod. “An Anchorite was a girl who lived like a hermit in a cell, but in the wall of a church. A living human sacrifice, in a way.”

Nestor drifts up. “One coffee. Say, is your friend hungry?”

“No, thank you,” says Holly. “I … I’ve got no appetite.”

“Come on,” I urge her, “you just walked from Columbus Circle.”

“I’ll bring a menu,” says Nestor. “You a veggie, like your friend?”

“She’s not my friend,” Holly fires back. “I mean, we just met.”

“Friend or not,” says the restaurateur, “a body’s got to eat.”

“I’ll be leaving soon,” declares Holly. “I have to rush.”

“Rush, rush, rush.” Nestor’s nasal hair streams in and out like seaweed. “Too busy to eat, too busy to breathe.” He turns away and turns back. “What’s next? Too busy to live?” Nestor’s gone.

Holly hisses: “Now you made me piss off an elderly Greek.”

“Order his moussaka, then. In my medical view, you don’t eat—”

“Since you’ve raised the subject of medical matters, ‘Dr. Fenby,’ I knew the name was familiar. I checked with Tom Ballantyne, my old GP. You came to my house in Rye when I was very nearly dying of cancer. I could have your medical license revoked.”

“If I was guilty of any malpractice, I would revoke it myself.”

She looks both outraged and baffled. “Why were you in my home?”

“Advising Tom Ballantyne. I was involved in trials of ADC-based drugs in Toronto, and Tom and I both thought your gall-bladder cancer might respond positively. It did.”

“You said you’re a psychiatrist, not an oncologist.”

“I’m a psychiatrist who owns a number of other hats.”

“So you’re claiming that I owe you my life now, are you?”

“Not at all. Or only partly. Cancer recovery is a holistic process, and while the ADCs contributed to your cancer’s remission, they weren’t the only curative agent, I suspect.”

“So … you got to know Tom Ballantyne beforemy diagnosis? Or … or … just how long have you been watching my life?”

“On and off, since your mother brought you into the consulting room in Gravesend Hospital in 1976.”

“Can you hear yourself? And it’s your actual job to curepeople of psychoses and delusions? Now for the last time, why did you send me a digitally jiggled image of a verybrief, veryex-boyfriend?”

“I want you to consider that the clause of life which reads ‘What lives must one day die’ can, in rare instances, be renegotiated.”

All the voices in the Santorini Cafй, all the gossiping, joking, cajoling, flirting, complaining, become, in my ears, a sonic waterfall.

Holly asks, “Dr. Fenby, are you a Scientologist?”

I try not to smile. “To believers in L. Ron Hubbard and the galactic Emperor Xenu, psychiatrists belong in septic tanks.”

“Immortality”—she lowers her voice—“isn’t—bloody—real.”

“But Atemporality, with terms and conditions applied, is.”

Holly looks around, and back. “This is deranged.”

“People said that about you after The Radio People.”

“If I could unwrite that wretched book, I would. Anyway, I don’t hear those voices any longer. Not since Crispin died. Not that that’s any of your goddamn business.”

“Precognition comes and goes,” I snowplow up some spilled sugar granules with my little finger, “mysteriously, like allergies or warts.”

“The big mystery to me is why I’m still sitting here.”

“Guess the name of Hugo Lamb’s mentor in the dark arts.”

“Sauron. Lord Voldemort. John Dee. Louis Cypher. Who?”

“An old friend of yours. Immaculйe Constantin.”

Holly rubs at a smear of lipstick on her coffee cup. “I never knew her first name. She’s only referred to as ‘Miss Constantin’ in the book. And in my head. So why are you inventing her first name?”

“I didn’t. It isher given name. Hugo Lamb’s one of her ablest pupils. He’s a superb groomer, and a formidable psychosoteric after only three decades following the Shaded Way.”

“Dr. Iris Marinus-Fenby, what bloody planet are you on?”

“The same one as you. Hugo Lamb now sources prey, just as Miss Constantin sourced you. And if she hadn’t scared you into reporting her so that Yu Leon Marinus was informed about and inoculated you, she would have abducted you and not Jacko.”

Chatter and clinking cutlery is loud and all around us.

Behind us, a girl is dumping her boyfriend in Egyptian Arabic.

“Now, I”—Holly pinches the bridge of her nose—“want to hit you. Reallyhard. What are, life-trespassing, fantasy-peddling … I—I—I have no words for you.”

“We’re truly sorry for the intrusion, Ms. Sykes. If there was any alternative at all, we wouldn’t be sitting here.”

“ ‘We’ being who, exactly?”

My back straightens a little. “We are Horology.”

Holly heaves a long, long sigh, meaning, Where do I start?

“Please.” I place a green key by her saucer. “Take this.”

She stares at it, then me. “What is it? And why would I?”

A couple of zombie-eyed junior doctors troop by, talking medical prognoses. “This key opens the door to the answers and proof you deserve and need. Once inside, go up the stairs to the roof garden. You’ll find me there with a friend or two.”

She finishes her coffee. “My flight home leaves at three P.M. tomorrow. I’ll be on it, heading home. Keep your key.”

“Holly,” I say gently, “I knowyou’ve met countless crazies thanks to The Radio People. I knowthe Jacko bait has been dangled at you before. But please. Take this key. Just in case I’m the real thing. It’s a thousand to one, I know, but I might be. Throw it away at the airport, by all means, but for now, take it. Where’s the harm?”

She holds my gaze for a few seconds, then pushes her empty cup and saucer away, stands, swipes up the key, and puts it into her handbag. She puts two dollars on the photo of Hugo Lamb. “That’s so I owe you nothing,” she mutters. “Don’t call me ‘Holly.’ Goodbye.”

April 5

IN THE SILT OF DREAMS, ill-wishers were cutting off my exits until the one way out was up. I can’t remember which self I am until I find my nightlight’s 05:09 imprinted on the overheated darkness. 119A. More than a mile away across Central Park on the ninth floor of the Empire Hotel, Arkady is preparing to dreamseed Holly Sykes with Фshima standing guard. I pray he won’t be needed. Staying here sticks in my craw, but if I went over to the Empire to help, I could end up triggering the very attack I so fear. Minutes limp by as I trawl New York’s nighttime tinnitus for meaning …

Pointless. I switch on my reading lamp, and gaze around my room. The Vietnamese urn, the scroll of the monkey regarding its own reflection, Lucas Marinus’s harpsichord from Nagasaki obtained by Xi Lo as a gift after a strenuous and improbable hunt … I turn to my place in Lucretius’s De Rerum Natura, but my thoughts, if not my soul, are still a mile or two to the west. This never-ending, accursed War. On my weakest days, I wonder why we Atemporals of Horology, who inherit resurrection as birthright, who possess what the Anchorites kill to obtain a twisted variation of, why don’t we just walk away from it? Why do we risk everything for strangers who’ll never know what we’ve done, win or lose? I ask the monkey troubled by its mirrored self: “Why?”

THE HOLY SPIRIT entered Oscar Gomez during last Sunday’s service at his Pentecostal church in Vancouver as the congregation recited Psalm 139. He described it to my friend Adnan Buyoya a few hours later as “knowing what lay in the hearts of his brothers and sisters in Christ, what sins they had yet to repent or to atone for.” Gomez’s conviction that God had bestowed this gift upon him was unshakable, and he was setting about God’s work without delay. He took the SkyTrain to Metropolis, a large suburban shopping mall in the city, and started preaching at the main entrance. Christian street preachers in secular cities are more ignored or mocked than they are listened to, but soon a crowd clotted around the short, earnest Mexican Canadian. Total strangers at Metropolis were baited, often to their astonishment, by Gomez’s startling specificity. One man, for example, was exhorted by Gomez to confess to fathering his sister-in-law Bethany’s baby. A hairdresser was begged to return the four thousand dollars she had stolen from her employer at the Curl Up and Dye hair salon. Gomez told a college dropout called Jed that the cannabis he was growing in his frail grandmother’s garden shed was disfiguring his life and could only end in a custodial sentence. Some blanched, their jaws dropping, and fled. Some angrily accused Gomez of hacking into their slates or working for the NSA, to which he replied, “The Lord has all our lives under surveillance.” Some began to weep, and ask for forgiveness. By the time the mall security guys arrived to escort Gomez from the premises, several dozen slates were filming the proceedings and a protective cordon of onlookers was surrounding the “Seer of Washington Street.” The city cops were summoned. YouTube uploads caught Gomez asking one of his arresters to confess to stamping on the head of an Eritrean immigrant—named—three nights before, while beseeching the other officer to seek counseling for his child pornography addiction, naming both the officer’s log-in and the Russian website. We can only guess at the conversation in the squad car, but en route to the precinct HQ, the destination was changed to Coupland Heights Psychiatric Hospital.

“Swear to God, Iris,” Adnan emailed me that evening, “I walked into the interview room and my first thought was, A seer? This guy looks straighter than my accountant. Straightaway—as if I’d spoken out loud—Oscar Gomez told me, “My father was an accountant, Dr. Buyoya, so maybe I get my straightness from him.” How do you conduct an assessment after that? I thought (or hoped?) I hadspoken my initial thought aloud, but soon Gomez was referring to those events from my boyhood in Rwanda that I’d only ever told you and my own analyst about during training.” In Adnan’s second email, sent two hours later, patients at Coupland Heights were worshiping the new inmate as a god. “It’s like ‘The Voorman Problem,’ ” Adnan said, referring to a Crispin Hershey novella we both admired. “I know what my grandparents would call Gomez in Yoruba, but there’s no way to talk about witchcraft in English and keep my job. Please, Iris. Can you help?”

VENI, VIDI, NON vici. By the time I’d located my car in the vast, rainy parking lot, I was drenched, and I got a run in my tights as I clambered in. I was also hammered by anger, despair, and a sense of impotence. I’d failed. My device warbled as a message arrived:

2late marinus 2late. will mrs gomez believe the truth?

Answers and implications slid into place, like a self-solving Rubik’s Cube. Topmost was the most obvious, that my device had been hacked by a Carnivore, a gloating Anchorite, who might be incautious and inexperienced enough to let his identity slip. I messaged a half-bluff:

hugo lamb buried his conscience but it never quite died

There was a chance that the “Saint Mark” who had promised to accompany Oscar Gomez up Jacob’s Ladder was “Marcus Anyder,” the Anchorite name of Hugo Lamb. My device sat in my clammy hand for one minute, two, three. Just as I gave up, a message arrived.

consciences r 4 bone clocks marinus, u r 1 beaten woman

My bluff had worked, unless I was being double-bluffed back. But, no, a carnivorous psychodecanter acting alone wouldn’t pass up the chance to rub my nose in my wrong guess, and the “beaten woman” phrase matched L’Ohkna’s profile of Hugo Lamb’s misogyny. As I considered how best to make use of this contact, surely unsanctioned by Constantin or Pfenninger, a third message arrived:

c yr future marinus c yr rearview mirror

Instinctively, I ducked and tilted the rearview mirror until I could see through the rear window. The glass was beaded with rain. I switched on the car’s battery, and clicked on the rear wiper, to remove the—

The passenger-side window exploded into a thousand tiny hailstones, and the mirror above my head was a brittle supernova of plastic and glass. One shard of plastic shrapnel, the size and shape of a fingernail clipping, lodged itself in my cheek.

I crouched, afraid. A logical portion of my mind was arguing that if the marksman had intended to kill me I would now be staring across the Dusk. But I stayed down for several minutes longer. Atemporality neutralizes death’s poison, but it doesn’t defang death, and old habits of survival linger on, even in us.

THAT IS WHY we prosecute the War, I remind myself in 119A, four days later. The window in my room turns under-ice gray. We bother because of Oscar Gomez, Oscar Gomez’s wife, and his three children. Because nobody else would believe in the animacides committed by a syndicate of soul thieves like the Anchorites or by “freelancers” hunting alone. Because if we spent our metalives amassing the wealth of empires and getting stoned on the opiates of wealth and power, knowing what we know yet doing nothing about it, we would be complicit in the psychoslaughter of the innocents.

My device buzzes. It’s Фshima’s tone. I fumble the thing like a panicky contestant, drop it, retrieve it, and read:

Done. No incidents.

Arkady returning now.

Will shadow Slim Hope.

I fill my lungs with oxygen and blessed relief. The Second Mission is one step closer. Daylight now leaks in around the window. 119A’s ancient plumbing shudders and clanks. I hear feet, a toilet cistern, and cupboard doors. Two or three rooms away, Sadaqat is up.

“SAGE, ROSEMARY, THYME …” Sadaqat, our warden, minder, and would-be traitor, plucks a weed from the raised beds. “I planted parsley too, so we could dine on ‘Scarborough Fair’ but late frost killed it. Some herbs are feebler than others. I’ll try again. Parsley’s rich in iron. Here I planted the onions and leeks, tough customers, and I have high hopes for the rhubarb. Do you remember, Doctor, we grew rhubarb at Dawkins Hospital?”

“I remember the pies,” I tell him.

We’re speaking quietly. Despite the fine-sieved rain and his busy night, Arkady, my fellow Horologist, is practicing Tai Chi among the myrtle and witch hazel across the rooftop courtyard. “This will be a strawberry patch,” Sadaqat points, “and the three fruiting cherry trees I’ll fertilize with the tip of a paintbrush, due to a scarcity of bees here in the East Side. Look! A red cardinal, on the momiji maple. I bought a book about birds, so I know. Those birds on the cloister roof, those are mourning doves. We have starlings nesting under the eaves, up there. They keep me busy with the scrubbing brush, but their droppings make a nutritious fertilizer, so I don’t complain. Here we have the fragrant quarter. Wintersweet, waxflower, and these thorny sticks will become scented roses. The trellis is for honeysuckle and jasmine.”

I notice that Sadaqat’s up-and-down British-Pakistani accent is flattening out. “You’ve worked magic up here, truly.”

Our warden purrs. “Plants want to grow. Just let them.”

“We should have thought of a garden up here decades ago.”

“You are too busy saving souls to think of such things, Doctor. The roof had to be reinforced, which was a challenge …”

Watch out, subwarns Arkady, or he’ll tell you about load-bearing walls and girders until you lose the will to live.

“… but I hired a Polish engineer who proposed a load-bearing—”

“It’s an oasis of calm,” I interrupt, “that we’ll cherish for years.”

“For centuries,” says Sadaqat, brushing droplets of mist off his vigorous but graying hair, “for you Horologists.”

“Let’s hope so.” Through an ornate wrought-iron screen in the cloister wall, we look down on the street four floors below. Cars crawl along and honk in vain. Umbrellas overtake them, parting for joggers running contraflow. Level with us on the much taller building across the road, an old woman with a neck brace waters the marigolds in her window boxes. New York’s skyscrapers vanish in cloud at about the thirtieth storey. If King Kong were up on the Empire State today, no one at our lowly altitude would believe the truth.

“Mr. Arkady’s Tai Chi,” Sadaqat murmurs, “reminds me of your magickings. How your hands draw on air, you know?” We watch him. Arkady may be gangly, Hungarian, and ponytailed, but the Vietnamese martial-arts master of his last self is still discernible, somehow.

I ask my former patient, “Are you still content with life here?”

Sadaqat is alarmed. “Yes! If I’ve done anything wrong …”

“No. Not at all. I just worry, sometimes, that we’re depriving you of friends, a partner, family … The trappings of normal life.”

Sadaqat removes his glasses and wipes them on his corduroy shirt. “Horology is my family. Partner? I am forty-five. I prefer to go to bed with The Daily Showon my slate, or a Lee Child novel and a cup of chamomile tea. Normal life?” He sniffs. “I have your cause, a library to explore, a garden to tend, and my poetry is becoming a little less awful. I swear, Doctor, every day when I shave I tell myself in the mirror, ‘Sadaqat Dastaani, you are the luckiest schizophrenic, middle-aged, balding, British Pakistani in all Manhattan.”

“If you ever,” I strive to sound casual, “think differently …”

“No, Dr. Marinus. My wagon is hitched to Horology’s.”

Careful,Arkady subwarns me, or he’ll smell a guilty rat.

I can’t quite let it go. “The Second Mission, Sadaqat. We can’t guarantee anyone’s safety. Not yours, not ours.”

“If you want me to go from 119A, Doctor, use your magickery-pokery because I won’t jump ship of my own accord. The Anchorites prey on the psychiatrically vulnerable, yes? If I’d had the correct type of”—Sadaqat taps his head—“soul, they might have taken me, yes? So. Horology’s War is my War. Yes, I am only a pawn, but a game of chess may hinge upon the conduct of a single pawn.”

Marinus, our guest’s arriving, Arkady subinforms me.

With a bruised conscience I tell Sadaqat, “You win.”

Our warden smiles. “I am glad, Doctor.”

“Our guest has arrived.” We walk back to the ironwork to look down on Holly in her Jamaican head-wrap. Across the road, Фshima shows his outline in the room we have above the violin maker’s: I’ll watch the street, he subsuggests, in case any interested parties pass by. Holly approaches the door with the green key I gave her yesterday at the Santorini Cafй. The Englishwoman’s having a very strange morning. On a wand of willow very near my shoulder, a puffed-up red-winged blackbird performs a loop of arpeggios.

“Who’s a handsome devil, then?” whispers Sadaqat.

I SPEAK FIRST. “We’ve been expecting you, Ms. Sykes. As they say.”

“Welcome to 119A.” Arkady’s voice has a teenage croaky waver.

“You’re safe, Ms. Sykes,” says Sadaqat. “Don’t be afraid.”

Holly is flushed after her climb, but upon seeing Arkady her eyes widen: “It isyou … you … you … isn’tit?”

“Yes, I have some explaining to do,” agrees Arkady.

Down in an alley, a dog is barking. Holly’s trembling. “I dreamtyou. This morning! You—you’re the same. How did you dothat?”

“The acne, right?” Arkady brushes his cheek. “Unforgettable.”

“My dream! You were at my desk, in my room, in my hotel …”

“Writing this address on the jotter.” Arkady picks up the sequence. “Then I asked you to bring Marinus’s green key here and go in. I said, ‘See you in two hours.’ And here we are.”

Holly looks at me, at Arkady, at Sadaqat, at me.

“Dreamseeding,” I comment, “is one of Arkaday’s mйtiers.”

“My range is lousy,” says my colleague, showing off his modesty. “My room was across the corridor from yours, Ms. Sykes, so I didn’t have far to transverse. Then, when my soul was back in my body, I hurried back here. In a taxi. Dreamseeding of civilians runs counter to our Codex, but you needed some proof of the wild claims made by Marinus the other day, and we’re at war, so I’m afraid we dreamseeded you anyway. Forgive us. Please.”

Holly’s at a nervous loss. “Who areyou?”

“Me? Arkady Thaly, as of this self. Hi.”

Up in the low cloud an airplane drags itself along.

“This is our warden,” I turn to Sadaqat, “Mr. Dastaani.”

“Oh, I’m just a glorified dogsbody, really,” says Sadaqat, “and normal, like you—well, ‘normal,’ eh? Call me Sadaqat. It’s said ‘Sa– dar-cutt’ with the stress on the ‘dar.’ Think of me as an Afpak Alfred.” Holly looks none the wiser. “Alfred? Batman’s butler. I take care of 119A when my employers are away. I cook. You’re vegetarian, I am told? So are the Horologists. It’s the”—he twirls his finger in the air—“body-and-soul thing. Who’s hungry? I’ve mastered eggs Benedict with smoked tofu, a fine breakfast for a disorienting morning. Could I tempt you?”

119A’S FIRST-FLOOR GALLERY is dominated by an elliptical table of walnut wood that was here when Xi Lo bought the house in the 1890s. The chairs are mismatched, from various eras since. Pearly light enters through the three arched windows. The paintings on the long walls were gifts to Xi Lo or Holokai from the artists: a blushing desert dawn by Georgia O’Keeffe, A. Y. Jackson’s view of Port Radium, Diego Quispe Tito’s Sunset over the Bridge of San Luis Rey, and Faith Nulander’s Hooker and John in Marble Cemetery. At one end is Agnello Bronzino’s Venus, Cupid, Folly, and Time. It is worth more than the building and its neighbors combined. “I know this one,” says Holly, staring at the Bronzino. “The original’s in the National Gallery, in London. I used to go and see it in my lunchbreak, when I worked at the homeless center at St. Martin in the Fields.”

“Yes,” I say. Holly doesn’t need a story about how the National’s copy and the original got switched in Vienna in 1860. Anyway, she’s moved on to the Bronzino’s unworthy companion, Self Portrait of Yu Leon Marinus, 1969. Holly recognizes the face and turns to me accusingly. I nod, sheepishly. “Absurd, of course, and sheer arrogance to hang it in this company, but Xi Lo, our founder, insisted. We keep it there for his sake.”

Sadaqat enters from the door by the astrolabe, bringing our drinks on a tray. Nobody has the stomach for eggs Benedict. He asks, “Now, where is everyone sitting?” Holly chooses the gondola chair at the end, nearest the way out. Sadaqat asks our guest, “Irish Breakfast blend, Ms. Sykes? Your mother’s Irish, I believe.”