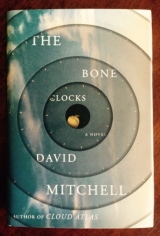

Текст книги "The Bone Clocks"

Автор книги: David Mitchell

Жанры:

Классическое фэнтези

,сообщить о нарушении

Текущая страница: 35 (всего у книги 40 страниц)

Holly stands up. I sedate her ankle and knees. Why?

“You were all talking about the War, but I didn’t even have a Swiss Army knife. So—yeah, I know, hysterical woman, rolling pin, big fat clichй, Crispin would’ve rolled his eyes and said, ‘Oh, come on!’ but I wanted … y’know … something. I hate the sight of blood so I left the knives in the drawer and … so. Shit, Marinus. What have I done?”

Killed a 250-year-old Atemporal Carnivore with a fifty-dollar kitchen implement, after putting on a fine impersonation of a sniveling, scared middle-aged woman.

“The sniveling part was easy.”

The Dusk’s coming, Holly. Which way now?

She pulls herself together. “A bit of light, please.” I half egress and glow, illuminating the narrow crossroads where the woman lying dead or dying ambushed us. “Which way were we going?”

We spun as we fell, I remember. And Constantin moved around us before she threatened us. I glow brighter, but this just enhances our view of a dead ambusher and a puddle of vomit. I can’t be sure.

Panic surges through Holly. I psychosedate it back down.

Then we hear the hum of the approaching Dusk. Shall I drive?

“Yeah,” Holly croaks. “Please.”

I look at the four passageways. They’re identical.

They’re not. One looks a little lighter. Holly, there’s only one way through the labyrinth, right?

“Yeah.”

I take the passage that leads to the light, turn right, and ten paces in front of us is the Dusk, filling the tunnel like starry, slow-motion water. There are voices in its smothered ululation. It doesn’t hurt, they say in unlabeled languages, it doesn’t hurt …

“What are we doing?” Holly’s voice rings out.

I turn back. This is the way we came in. The Dusk’s following us. We came to the crossroads—here.I step us over Constantin’s body. Picture Jacko’s maze in your head again. The pendant.

“I’ve got it. Straight on.” I obey. “Left. There’ll be a turning to the right, but ignore it, it’s a dead end … Keep going. Through the next right.” I pass through the tunnel, thinking of the Dusk spilling over Constantin’s body. “Left. On a few paces … On a few more, we’re near the middle, but we have to go out in a circle to avoid a trap ahead. That’s this next left. Go on, through the arch … Now turn right.” I walk a few paces, still hearing the slosh of the Dusk catching up as the ever-shortening side tunnels and dead ends drain off less and less of its mass and energy. “Ignore that gap to your left … Now turn right. Over the crossroads. Hurry! Turn right, turn left, and we should be—” The archway before us is black, not black with shadow, but solid black, black like the Last Sea is black, a blackness that absorbs the chakra-light I shine from Holly’s palms and bounces nothing back.

I step into—

–A DOMED ROOM of the same dead Mars-red walls as the labyrinth, but alive with the sharp shadows of many birds. The room is lit by the evening light of a golden apple. “My …” Despite all we’ve seen today, Holly’s breath catches in her throat. “Look at it, Marinus.” The apple hangs in the middle of the chamber, at head-height, with no means of support. “Is it alive?” asks Holly.

I would say, I subspeculate, it’s a soul.

Golden apples I’ve heard of in poems and tales throughout my metalife. Golden apples I’ve seen in paintings, and not just the one Venus holds in the Bronzino original that Xi Lo knew so well, though that golden apple strengthens my suspicions about this one. I’ve even held an apple wrought from Kazakh gold in the eleventh century by a craftsman at the court of Suleiman VI, with a leaf of emerald-studded Persian jade and dewdrops of pearl from the Mauritius Islands. But the difference between those golden apples and this one is the difference between reading a love poem and being in love.

Holly’s eyes are welling. “Marinus …”

It’s our way back, Holly. Touch it.

“ Touchit? I can’t touch it. It’s so …”

Xi Lo created it for you, for this moment.

She takes a step closer. We hear air in feathers.

One touch, Holly. Please. The Dusk’s coming.

Holly reaches out her well-worn, grazed hand.

As I egress from my host, I hear a dove trill.

Holly is gone.

THE SHADOW-BIRDS VANISHED with the apple, and the domed chamber feels like a rather dingy mausoleum. Now I die. I die-die. But I die knowing that Holly Sykes is safe, knowing that a debt Horology owed her has been paid. This is a good way to finish. Aoife still has a mum. I invoke a pale gleam and subask Hugo Lamb, Why die alone?

He uncloaks and melts out of the air. “Why indeed?” He touches his badly gashed cheek. “Oh, shit, look at the state of me! Bloody dinner jackets. My tailor’s this Bangladeshi chap in Savile Row, and he’s a genius, but he only makes twenty suits a year. Why did Xi Lo only leave the one magic ticket back to the world?”

I transverse to where the golden apple hung. Every subatomic particle of it is gone. Transubstantiation’s draining. The Blind Cathar kept getting fed fresh meat, remember. Xi Lo sustained all this on batteries. Why didn’t you take the one magic ticket back?

He dodges the question. “Got any cigarettes on you, Marinus?”

I’m incorporeal. I don’t even have a body on me.

A trickle of Dusk appears from the black doorway, like sand.

You’ve sourced, lied, I subsay, groomed, lured, murdered … “They were clinical murders. They died happy. Ish.”

… as Marcus Anyder, you even killed your old self.

“Do you really want to spend your final moments interviewing me? What do you want? Some big dramatic mea culpa?”

I’m just curious as to why a predator, I subspell out the obvious, who has thought about nothing but himself for so many years, and who only last week gloated about killing Oscar Gomez, should now—

“You’re not still angry about that, are you?”

– should now nobly lay down his artificially suspended life for a common bone clock. Go on. I promise I won’t tell a soul.

The muttering of the Dusk is growing. I push the voices away.

Hugo Lamb dusts his sleeves. “You scansioned Holly, I presume?”

Extensively. I had to, to locate Esther Little.

“Did you find us in La Fontaine Saint-Agnиs? Holly and I?”

I hesitate too long.

“So you had a good gawp. Well. Now you have your answer.” More Dusk spills in, promising us it won’t hurt, it won’t hurt, it won’t hurt. A third of the floor is covered now. “Did you see her lay into Constantin? Irish blood, Gravesend muscle. Talk about breeding.”

You stood by andwatched that?

“Never been the have-a-go-hero type, me.”

Constantin recruited you. She was the Second Anchorite.

“I’ve always had a problem with authority figures. Rivas-Godoy turned right when we entered the labyrinth, so that was him finished from the outset, but I followed Constantin. Yes, she recruited me, but she bought into the women-and-children-first doctrine bigtime. So I cloaked myself, got lost, heard Holly, followed you … And here we are. Death-buddies. Who would have thought it?” We watch the sandy Dusk fill the domed chamber, getting deeper. I’m nagged by a thought that I’ve missed something obvious. Hugo Lamb coughs. “Did she love me too, Marinus? I don’t mean after she found out about my little … dalliance with a paranormal cult that scarred her family and attempted to animacide her brother. I mean, that night. In Switzerland. When we were young. Properly young. When Holly and I were snowed in.”

Two-thirds of the floor is covered. Lamb the corporeal has sixty seconds of life before the Dusk reaches him. I can hover a little longer, until the dome is full to the roof, if I really want to.

Then it hits me, what I’ve missed. Hugo Lamb missed it too. Even Constantin missed it. Dodging falling masonry, trying to avoid the Dusk, we all forgot an alternative exit. I could sublaugh. Will it work? If the Dusk got into the Way of Stones and erased the conduit, no … But it was a long way down.

I subask Lamb, How much voltage do you have left?

“Not a lot. Why? Fancy a psychoduel?”

If I ingress you, we might have enough together.

He’s confused. “To do what?”

To summon the Aperture.

October 26

AT THE FOOT OF THE STAIRS I hear this thought, He is on his way, and goosebumps shimmy up my arms. Who? Up ahead, Zimbra turns to see what’s keeping me. I sift the sounds of the late evening. The stove, clanking as it cools. Waves, shoulder-barging the rocks below the garden. The creaking bones of the old house. The creaking bones of Holly Sykes, come to that. I lean over the banister to peer through the kitchen-sink window up the slope to Mo’s bungalow. Her bedroom light’s on. All well there. No feet on the gravel garden path. Zimbra doesn’t sense a visitor. The hens are quiet, which at this hour is the way we want it. Lorelei and Rafiq are giggling in Lorelei’s room, playing shadow puppets: “That looks nothing likea kangaroo, Lol!”; “How would youknow?”; “Well, how would youknow?” Not so very long ago, I thought I’d never hear my two orphans laugh like that again.

So far so normal. No more audible thoughts. Someone’s always on their way. But, no, it was “ Heis on his way,” I’m sure. Or as sure as I can be. The problem is, if you’ve heard voices in your head once, you’re never sure again if a random thought isjust a random thought, or something more. And remember the date: the five-year anniversary of the ’38 Gigastorm, when Aoife’s and Цrvar’s 797 got snapped at twenty thousand feet, theirs and two hundred other airliners crossing the Pacific, snapped like a boy in a tantrum snapping the Airfix models Brendan used to hang from his bedroom ceiling.

“Oh, ignore me,” I mutter to Zimbra, and carry on up the stairs, the same stairs I once flew up and flew down. “Come on,” I tell Zimbra, “shift your bum.” I stroke the whorl of fur between his ears, one sticky-uppy and one floppy. Zimbra looks up, like he’s reading my mind with those big black eyes. “You’d tell me if there was anything to worry about, wouldn’t you, eh?”

Anything elseto worry about, that is, besides the fear that the dragging feeling in my right side is my cancer waking up again; and about what’ll happen to Lorelei and Rafiq when I die; and about the Taoiseach’s statement about Hinkley Point and the British government’s insistence that “a full meltdown of the reactor at Hinkley E is not going to happen”; and about Brendan, who lives only a few miles from the new exclusion zone; and about the Boat People landings near Wexford, and where and how these thousands of hungry, rootless men, women, and children will get through the winter; and about the rumors of Ratflu in Belfast; and our dwindling store of insulin; and Mo’s ankle; and …

Worrying times, Holly Sykes.

“I KNEW THAT was going to happen!” says Rafiq, swamped in Aoife’s old red coat that now serves as his dressing gown, hugging his knees at the foot of Lorelei’s bed. “When Marcus found the brooch was missing from his cloak, that was a—a deadgiveaway, like. You can’t nick a golden eagle from a tribe like the Painted People and expect to get away with it. For them, it’s like Marcus and Esca have stolen God. Of coursethey’ll come and hunt them down.” Then, ’cause he knows how much I love The Eagle of the Ninth, he tries his luck: “Holly, can’t we have just a bit of the next chapter?”

“It’s almost ten,” says Lorelei, “and school tomorrow,” and if I close my eyes I can almost imagine it’s Aoife at fifteen years old.

“All right. And is the slate recharged?”

“Yes, but there’s still no thread and no Net.”

“Is it reallytrue,” Rafiq shows no sign of shifting from Lorelei’s bed, “that when you were my age you used to get as much electricity as you wanted allthe time, like?”

“Do I detect a bedtime postponement tactic, young man?”

He grins. “Must’ve been magnoto have all that electricity.”

“It must’ve been what?”

“Magno. Everyone says it. Y’know: boss, class, epic, good.”

“Oh. Looking back, yes, it was ‘magno,’ but we all took it for granted back then.” I remember Ed’s pleasure at unlimited electricity each time he got back to our little house in Stoke Newington from Baghdad, where he and his colleagues had to power their laptops and satellite phones with car batteries brought by the battery guy. Sheep’s Head could do with a battery guy now, but his truck’d need diesel, and there isn’t any spare, which is why we need him.

“And airplanes used to fly allthe time, right?” sighs Rafiq. “Not just people from Oil States or Stability?”

“Yes, but …” I flounder for a way to change the subject. Lorelei, too, must be thinking dark thoughts about airplanes tonight.

“So where did you go, Holly?” Rafiq never tires of this conversation, no matter how often we do it.

“Everywhere,” says Lorelei, being brave and selfless. “Colombia, Australia, China, Iceland, Old New York. Didn’t you, Gran?”

“I did, yes.” I wonder what life in Cartagena, in Perth, in Shanghai is like now. Ten years ago I could have streetviewed the cities, but the Net’s so torn and ragged now that even when we have reception it runs at prebroadband speed. My tab’s getting old, too, and I only have one more in storage. If any arrive via Ringaskiddy Concession, they never make it out of Cork City. I remember the pictures of seawater flooding Fremantle during the deluge of ’33. Or was it the deluge of ’37? Or am I confusing it with pictures of the sea sluicing into the New York subway, when five thousand people drowned underground? Or was that Athens? Or Mumbai? Footage of catastrophes flowed so thick and fast through the thirties that it was hard to keep track of which coastal region had been devastated this week, or which city had been decimated by Ebola or Ratflu. The news turned into a plotless never-ending disaster movie I could hardly bring myself to watch. But since Netcrash One we’ve had hardly any news at all and, if anything, this is worse.

The wind shakes the windowpane. “Lights out now. Let’s save the bulb.” I have only six bulbs left, too, stowed under the floorboards in my bedroom with the final slate since the spate of break-ins up Durrus way. I kiss Rafiq’s wiry-haired head as he traipses out to his tiny room, and tell him, “Sweet dreams, love.” I mean it, too: Rafiq’s nightmares are down to one night in ten, but when they come his screams could wake the dead.

Rafiq yawns. “You too, Holly.”

Lorelei snuggles down under her blankets and sheepskin as I close her door. “Sleep tight, Gran, don’t let the bedbugs bite.” Dad used to say that me, I used to say it to Aoife, Aoife passed it on to Lorelei, and now Lorelei says it back to me.

We live on, as long as there are people to live on in.

IT’S PROPERLY DARK, but now I’m in my seventies, I need only a few hours—one of the rare compensations of old age. So I feed the stove another log, turn up the globe, and get out my sewing box to patch an old pair of Lol’s jeans so Rafiq can inherit them, and then I need to repair some socks. Wish I could stop longing for a hot shower before bed. Occasionally Mo and I torment each other with memories of the Body Shop, and its various scents: musk and green tea, bergamot, lily-of-the-valley; mango, brazil nut, banana; coconut, jojoba oil, cinnamon … Rafiq and Lorelei’ll never know these flavors. For them, “soap” is now an unscented block from “the Pale,” as the Dublin manufacturing zone is known. Until last year you could still buy Chinese soap at the Friday market, but whatever black-market tentacle got it as far as Kilcrannog has now been lopped off.

When I’m sure the kids are asleep, I turn on the radio. I’m always nervous that there’ll just be silence, but it’s okay: All three stations are on air. The RTЙ station is the mouthpiece of Stability and broadcasts officially approved news on the hour with factual how-to programs in between about growing food, repairing objects, and getting by in our ever-more-makeshift country. Tonight’s program is a first-aid repeat about fitting a splint to a broken arm, so I switch to JKFM, the last private station in Ireland, for a little music. You never know what you’ll get, though obviously it’s all at least five years old. I recognize the chorus of Damon MacNish and the Sinking Ship’s “Exocets for Breakfast,” and remember a party in Colombia, or was it Mexico City?, where I met the singer. Crispin was there as well, if I’m not wrong. I know the next song, too: “Memories Can’t Wait” by Talking Heads, but it reminds me of Vinny Costello so I try our third station, Pearl Island Radio. Pearl Island Radio is broadcast from the Chinese Concession at Ringaskiddy, outside Cork. It’s mostly in Mandarin, but sometimes there’s an international news bulletin in English, and if the Net’s unthreaded this is the only way to get news unfiltered by Stability. Of course, the news has a pro-Chinese slant—Ed would call it “naked propaganda”—and there’ll be not a whisper about Hinkley E, which was built and operated by a Chinese-French firm until the accident five years ago when the foreign operators pulled out, leaving the British with a half-melted core to ineffectively contain. There’s no English news tonight, but the sound of the Chinese speakers soothes my nerves and, inevitably, I think of Jacko; and then of those days and nights with the Horologists in New York, and out of New York, nearly twenty years ago …

THE CHAPEL, THE battle, the labyrinth: Yes, I believe it all took place, even though I know that if I ever described what I saw, it’d sound like attention-seeking, insanity, or bad drugs. If it’d just been the trippier parts that I remembered, if I’d woken up in my room at the Empire Hotel, I might be able to put it down to delusion, or food poisoning, or an “episode” with memory loss, or false memories. There’s too much other stuff that won’t be explained away, though: Stuff like how, after touching the golden apple in the domed room of the bird shadows I vanished in a head-rush of vertigo and found myself not waking up in my hotel room but in the gallery at 119A, with my middle finger touching the golden apple on the Bronzino picture, a dove trilling on the windowsill outside, and all the Horologists gone. The marble rolling pin was missing from the kitchen drawer. My knees were scabbed and sore from when Constantin ambushed me in the labyrinth. I never knew why Marinus didn’t travel back in my head—maybe the golden apple only worked for one passenger. Last of all, when evening came and I gave up waiting for a friendly Atemporal to appear, I got a cab across Central Park back to my room, where I found all charges for the week had been paid by a credit card that wasn’t mine. If a New York hotel receptionist tells you your room’s been paid for, you can bet your life you weren’t dreaming it.

So, yes, it happened, but ordinary life carried on at the speed of time, and the following day doesn’t care about all your paranormal adventures in the days before. To the cabdriver, I was just another fare to LaGuardia Airport who’ll leave her glasses on the backseat if he doesn’t check. To the Aer Lingus air steward, I was just another middle-aged lady in economy whose earphones weren’t working. To my hens, I’m a two-legged giant who throws them corn and keeps stealing their eggs. During my “lost weekend” in Manhattan I may have seen a facet of existence that only a few hundred in history have glimpsed, but so what? I could hardly tell anyone. Even Aoife or Sharon would’ve gone, “I believe you believe it, but I think you may need professional help …”

There has been no sequel. Marinus, if she got out of that domed room, has never reappeared and it isn’t going to happen now. I streetviewed 119A a few times and found the tall brownstone townhouse with its varied windows, so someone’s still looking after it—New York real estate is still New York real estate, even as America disintegrates—but I’ve never been back, or tried to find out who’s living there. Once I deviced the Three Lives Bookstore, but when a bookseller answered, I chickened out and hung up before asking if Inez still lived upstairs. One of the last books Sharon sent me before post from Australia stopped getting through was about the twelve Apollo astronauts who walked on the moon, and I sort of felt my time in the Dusk was a bit like that. And now that I was back on earth, I could either go slowly crazy by trying to get back to that other realm, to psychosoterica and 119A and Horology, or not, and just say, “It happened, but it’s over,” and get on with the ordinary stuff of family and life. At first, I wasn’t sure if I could, I dunno, write up the minutes for the Kilcrannog Tidy Towns Committee, knowing that, as we sat there discussing grants for the new playground, souls were migrating across an expanse of Dusk into a blankness called the Last Sea—but I found I could. A few weeks before my sixteenth birthday, I met a woman twice my age in an abortion clinic in the shadow of Wembley Stadium. She was posh and composed. I was a scared, weepy mess. As she lit a new cigarette from the dying ember of the last one, she told me this: “Sweetheart, you’ll be astounded by what you can live with.”

Life has taught me that she was right.

… Zimbra’s barking in my dreams. I wake up in my chair next to the stove, and Zimbra’s still barking, on the side porch. Fuddled, I get up, dropping the half-darned sock, and walk over to the porch: “Zimbra!” But Zimbra can’t hear me; Zimbra’s not even Zimbra, he’s a primeval canine scenting an ancient enemy. Is anyone out there? God, I wish the old security floodlight was still working. Zimbra’s barking stops for one second—long enough for me to hear the terror of hens. Oh, no, not a fox. I grab the torch, open the door only a crack but our dog barges through and scrabbles at what’s probably the fox’s hole under the wire. Dirt flies over me and the chickens are going berserk around the wire walls of their coop. I shine the torch in and can’t see the fox but Zimbra’s in no doubt. One dead hen; two; three; one feebly flapping; and there, two disks on the head of a reddish blur on top of the hen coop. Zimbra—fifteen kilos’ worth of German shepherd crossed with black Labrador with bits of the devil knows what else—squeezes into the cage and launches himself at the henhouse, which topples over while the hens squawk and flap around the wire-mesh enclosure. Quick as a whip, the fox leaps back to the hole and its head’s actually through before Zimbra’s sunk his fangs into its neck. The fox looks at me for a split second before it’s yanked back, shaken, flung, and pounced on. Then its throat’s ripped out and it’s all over. The hens keep panicking until one notices the battle’s over, then they all fall quiet. Zimbra stands over his prey, his maw bloodred. Slowly he returns to himself and I return to myself. The porch door opens and Rafiq’s standing there in his dressing gown. “What happened, Holly? I heard Zim going mental.”

“A fox got into the chickens, love.”

“Oh, bloody hell, no!”

“Language, Rafiq.”

“Sorry. But how many did it get?”

“Only two or three. Zim killed it.”

“Can I see it?”

“No. It’s a dead fox.”

“Can we eat the dead chickens, at least?”

“Too risky. Specially now rabies is back.”

Rafiq’s eyes go even wider: “ Youweren’t bitten, or …”

Bless him. “Back to bed, mister. Really, I’m fine.”

SORT OF. RAFIQ has plodded upstairs and Zimbra is locked on the porch. It’s four dead hens, not three, which is a medium-sized loss, with eggs being my main bartering token at the Friday market, as well as Lorelei and Rafiq’s main source of protein. Zimbra looks okay, but I can only hope he doesn’t need veterinary attention. Synthetic meds for humans have all but dried up; if you’re a dog, forget it. I turn down the solar, dig out a bottle of Declan O’Daly’s potato hooch, and pour myself what Dad would’ve called a goodly slug. I let the alcohol cauterize my nerves and look at the backs of my old, old hands. Ridged tendons, snaky veins, vacuum-packed. My left hand trembles a little these days. Not much. Mo’s noticed, but pretends not to. If you’re Lol and Raf’s age, all old people’re trembly, so they’re not worried. I pull my blanket over me, like Little Red Riding Hood’s grandmother, who I feel like, in fact, in a world of too many wolves and not enough woodcutters. It’s chilly out. Tomorrow I’ll ask Martin the Mayor if we’re likely to see a delivery of coal this winter, though I know he’ll just say, “If we see any, Holly, the answer’s yes.” Fatalism’s a weak antidepressant, but there’s nothing stronger at Dr. Kumar’s. Through the side window I see my garden chalkdusted by the nearly full moon, rising over the Mizen Peninsula. I should harvest the onions soon and plant some kale.

In the window I see a reflection of an old woman sitting in her great-aunt’s chair and I tell her, “Go to bed.” I haul myself to my feet, ignoring the twinge in my hip, but pausing for a moment at the little driftwood box shrine we keep on the dresser. I made it five years ago during the worst grief-numbed weeks after the Gigastorm, and Lorelei decorated it with shells. Aoife and Цrvar’s photo is inside, but tonight I just stroke my thumb across the top edge, trying to remember how Aoife’s hair felt.

“Sleep tight, sweetheart, don’t let the bedbugs bite.”

October 27

UP BEFORE DAWN to pluck the feathers from four dead hens. Only twelve hens left, now. When I first moved to Dooneen Cottage—a quarter of a century ago—I couldn’t have plucked a hen if my life depended on it. Now I can stun, decapitate, and gut one as casually as Mam used to make a beef and Guinness stew. Necessity’s even taught me how to skin and dress rabbits without puking. One old fertilizer bag of feathers later I put the dead hens into the wheelbarrow and walk down the end of the garden via the hen coop, where I add the fox’s body to my one-wheeled hearse. He’s male, I see. Don’t touch fox’s tails, Declan says. A fox’s brush is a bacteriological weapon, barbed with disease. Probably got fleas, too, and we’ve had enough trouble with fleas, ticks, and lice as it is. The fox looks like he’s having an afternoon nap, if you ignore the ripped-out throat. One of his fangs protrudes slightly, pressing in his lower lip. Ed’s tooth did that. I wonder if the fox has cubs and a mate. I wonder if the cubs’ll understand that he’s never coming back, if the heart’ll be ripped out of their lives, or if they’ll just carry on foraging without a second thought. If they do, I envy them.

The sea’s ruffled this morning. I think I see a couple of dolphins a few hundred yards out, but when I look again, they’ve gone, so I’m not sure. The wind’s still from the west and not the east. It’s an awful thing to think, but if Hinkley is spewing radioactive material, which way the wind happens to be blowing could be a matter of life or death.

I tip the wheelbarrow’s grisly cargo off the stone pier. I never name our hens, ’cause it’s harder to wring the neck of something you’ve named, but I’m sad they had such frightened deaths. Now they’re drifting away with their killer into the open bay.

I want to hate the fox, but I can’t.

It was only trying to survive.

BACK AT THE house, Lorelei’s in the kitchen spreading a bit of butter on yesterday’s rolls for her and Rafiq’s lunch. “Morning, Gran.”

“Morning. There’s dried seaweed, too. And pickled turnip.”

“Thanks. Raf told me about the fox. You should’ve woken me.”

“No point, love. You can’t raise chickens from the dead, and Zim dealt with the fox.” I wonder if she’s remembered the date. “There’s a few strips of corrugated iron from the old shed—I’ll try sinking some underground walls around the coop.”

“Good idea. It should ‘outfox’ the next visitor.”

“That’s one gene you inherited from Granddad Ed.”

She likes it when I say that sort of thing. “It’s, uh,” she makes an effort to sound breezy, “Mum and Dad’s Day, today. The twenty-seventh of October.”

“It is, love. Want to light the incense?”

“Yes, please.” Lorelei goes to the little box shrine and opens up its front. The photo shows Aoife and Цrvar and a ten-year-old Lorelei, against the background of a dig at L’Anse aux Meadows. It was taken in spring of 2038, the year they died, but its greens and yellows are already fading and the blues and magentas blotting. I’d pay a lot for a reprint but there’s no power or ink cartridges to print one, and no original to make a reprint from; my feckless generation trusted our memories to the Net, so the ’39 Crash was like a collective stroke.

“Gran?” She’s looking at me like my mind’s gone walkabout.

“Sorry, love, I was, um …” Often, there are just blanks.

“Where’s the tin with the incense sticks?”

“Oh. I tidied it up. Put it somewhere safe. Um …” Is this happening more these days? “The tin, above the stove.”

Lorelei lights the new incense stick at the stove, then blows out the tiny flame. She crosses the kitchen, placing the stick in the holder in the little shrine. On the ledge are a Roman coin, which Aoife gave to Lorelei, and an old windup watch Цrvar inherited from his grandfather. We watch the sandalwood smoke unthread itself from the glowing tip. Sandalwood, yet another old-world scent. The first year we did this, I’d prepared a prayer and a poem, but I started weeping so uncontrollably that I appalled Lorelei; since then we’ve tacitly agreed that we just stand here for a little while and sort of be alone together with our memories. I remember waving them off at Cork airport five years ago—the last year that ordinary people could buy diesel, drive cars, and fly, though ticket prices were spiraling through the roof, and they couldn’t have gone if the Australian government hadn’t paid Цrvar’s way. Aoife went to see her aunt Sharon and uncle Peter, who’d moved out there in the late twenties and who I hope are still alive and well in Byron Bay, but there’ve been no news-threads to—and precious little information from—Australia for eighteen months. How easily, how instantly we used to message anyone, anywhere on earth. Lorelei holds my hand. She would’ve gone with her parents if she hadn’t been getting over chicken pox, so Aoife and Цrvar drove her here from Dublin, where they were living that year. A fortnight with Grandma Holly was the consolation prize.