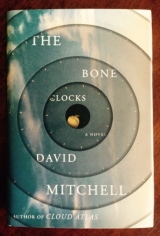

Текст книги "The Bone Clocks"

Автор книги: David Mitchell

Жанры:

Классическое фэнтези

,сообщить о нарушении

Текущая страница: 31 (всего у книги 40 страниц)

“The professor is a friend,” said my foster mother.

“And a classical linguist of the first rank,” I added.

“Indeed. Well, Professor Andropov told me that the ‘K’ stood for ‘Klara’; and then, on our way home, by chance I glanced out of our coach and saw your father’s church. A hobgoblin told me to see if you were at home, and I’m afraid that I”—Claudette Davydov asked her husband in Arabic how to say the word “succumbed” in Russian, and Shiloh Davydov repeated it for her—“I succumbed.”

“My, my,” said Vasilisa, blinking at the exotic strangers whom she’d apparently invited into her house. “My. You’re both welcome, I’m sure. My husband will be home presently. Make yourselves as comfortable as you can, I beg you. This is not a palace but …”

“No palace Iever saw was half so friendly.” Shiloh Davydov looked around our parlor. “My wife’s been excited about meeting ‘K. Koskov’ since the day I resolved to visit Petersburg.”

“Indeed I have.” Claudette Davydov handed Galina her muff of white fur with murmured thanks. “And to judge from Miss Koskov’s surprise, we both wrote to the other in the mistaken belief that the other was a man—do I surmise correctly, Miss Koskov?”

“I cannot deny it, Mrs. Davydov,” I said, as we all sat down.

“Is it not too much like an absurd farce for the stage?”

“A wrongheaded world,” sighed Shiloh Davydov, “where women needs must deny their gender for fear that their ideas will be dismissed.”

We considered the truth of this. “Klara dear,” said Vasilisa, remembering her duty as hostess, “would you feed up the fire while Galina brings refreshments for our guests?”

“THE SEA IS my business, sir,” replied Shiloh Davydov. Dmitry found the Davydovs’ unexpected company to his liking, and for the men the tea and cakes were superseded by brandy and the box of cigars Shiloh had presented to my foster father. “Shipping, freight, shipyards, shipbuilding, maritime insurance …” He waved a hand vaguely. “I’ve journeyed to Petersburg at the behest of the Russian Admiralty, so naturally I must be discreet about details. We shall be employed here for a year at least, however, and I’ve been granted the use of a government house on Mussorgsky Prospect. Mrs. Koskov, how difficult will it be to engage domestic staff who are both capable and honest? In Marseille, I’m sorry to say, the combination is as rare as hen’s teeth.”

“The Chernenkos will help,” said Vasilisa. “For Dmitry’s uncle, Pyotr Ivanovich, and his wife, finding a few hen’s teeth is a small matter. Is it not, Dmitry?”

“They’ll come wrapped in a Golden Fleece, knowing Pyotr.” Dmitry puffed appreciatively on his cigar. “How do you intend to wile away your months in our frozen northern wastes, Mrs. Davydov?”

“Like my husband, I have the soul of an explorer,” said Claudette Davydov, as if that were a full answer. The fire spat sparks. “First, though, I intend to finish a commentary on Ovid’s Metamorphoses. I had even entertained hopes that ‘K. Koskov’ would pay me the honor of casting her eye over my scribblings, if …”

I said that the honor would be mine, and that we clandestine female scholars were duty-bound to band together. Then I asked if “C. Holokai” had received my last letter, sent the previous August to the Russian legate in Marseille.

“Indeed I did,” said Claudette Davydov. “My husband, whose love of philosophy is, as you see, as deep as my own, was as fascinated as I was to read about your notion of the Dusk.”

Now Vasilisa was curious. “What dusk would that be, dear?”

I disliked lying even by omission to my foster parents, but Atemporality in a Godless, godless universe was not a profitable topic of discussion in our pious household. As I fabricated a prosaic explanation, my glance fell on Shiloh Davydov. His eyes had half closed and a spot glowed in what I knew from my Eastern resurrections was a chakra-eye. I looked at Claudette Davydov. The same spot glowed. Something was happening. I looked at my foster parents and saw that Vasilisa and Dmitry Koskov were as still as living waxworks. Vasilisa still wore her look of concentration, but her mind appeared to have shut down. Or have been shut down. Dmitry’s cigar smoked in his fingers, but his body was motionless.

After twelve hundred years I had come to think of myself as immune to shock, but I was wrong. Time had not stopped. The fire still burned. I could still hear Galina chopping vegetables out in the kitchen. By instinct, I searched for a pulse in Vasilisa’s wrist and found it, strong and steady. Her breathing was slow and shallow but steady. The same was true for Dmitry. I said their names. They didn’t hear me. They weren’t here. There could be only one cause or, more likely, a pair of causes.

The Davydovs, meanwhile, had returned to normal and were awaiting my response. Standing, feeling out of my depth but furious, I grabbed the poker and told the Davydovs, or whatever the Davydovs were, in a manner not at all like a twenty-year-old Russian priest’s daughter, “If you’ve harmed my parents, I swear—”

“Why would we harm these sincere people?” Shiloh Davydov was surprised. “We’ve performed an Act of Hiatus on them. That’s all.”

Claudette Davydov spoke next: “We were hoping for a private audience with you, Klara. We can unhiatus your foster parents like that”—she clicked her fingers—“and they won’t know they were gone.”

Still viewing the Davydovs as threats, I asked whether a “hiatus” was a phenomenon akin to mesmerism.

“Franz Mesmer is a footling braggart,” replied Claudette Davydov. “We are psychosoterics. Psychosoterics of the Deep Stream.”

Seeing that these words only baffled me, Shiloh Davydov asked, “Have you not witnessed anything like this before, Miss Koskov?”

“No,” I replied. The Davydovs looked at each other, surprised. Shiloh Davydov removed the cigar from Dmitry’s fingers before it scorched them, and rested it in the ashtray. “Won’t you put that poker down? It won’t help your understanding.”

Feeling foolish, I replaced the poker. I heard horses’ hoofs, the jink of bridles, and the cries of a coalman on Primorsky Prospect. Inside our parlor my metalife was entering a new epoch. I asked my guests, “Who areyou? Truly?”

Shiloh Davydov said, “My name is Xi Lo. ‘Shiloh’ is as close as I can get in Europe. My colleague here, who is obliged to be my wife in public, is Holokai. These are the true names we carry with us from our first lives. Our souls’ names, if you will. My first question for you, Miss Klara Koskov, is this: What is your true name?”

In a most unladylike way, I drank a good half of Dmitry’s brandy. So long ago had I buried the dream that I’d one day meet others like me, other Atemporals, that now it was happening, I was woefully, woefully unprepared. “Marinus,” I said, though it came out as a husky squeak, thanks to the brandy. “I am Marinus.”

“Well met, Marinus,” said Claudette Holokai Davydov.

“I know that name,” frowned Xi Lo–in–Shiloh. “How?”

“You would not have slipped my mind,” I assured him.

“Marinus.”Xi Lo stroked his sideburns. “Marinus of Tyre, the cartographer? Any connection? No. Emperor Philip the Arab had a father, Julius Marinus. No. This isan itch I cannot scratch. We glean from your letter that you’re a Returnee, not a Sojourner?”

I confessed that I didn’t understand his question.

The pair looked unsettled by my ignorance. Claudette Holokai said, “Returnees die, go to the Dusk, are resurrected forty-nine days later. Sojourners, like Xi Lo here, just move on to a new body when the old one’s worn out.”

“Then, yes.” I sat back down. “I suppose I am a Returnee.”

“Marinus.” Xi Lo–in–Shiloh watched me. “Are we the first Atemporals you ever met?”

The lump in my throat was a pebble. I nodded.

Claudette-Holokai stole a drag of her companion’s cigar. “Then you’re handling yourself admirably. When Xi Lo broke my isolation, the shock drove away my wits for hours. Some may say they never returned. Well. We bear glad tidings. Or not. There are more of us.”

I poured myself more brandy from Dmitry’s decanter. It helped to dissolve the pebble. “How many of you—of us—are there?”

“Not a large host,” Xi Lo answered. “Seven of us are affiliated in a Horological Society housed in a property in Greenwich, near London. Nine others rejected our overtures, preferring isolation. The door to them stays open if they ever wish for company. We encountered eleven—or twelve, if we include the Swabian—‘self-elected’ Atemporals down the centuries. To cure these Carnivores of their predatory habits is a principal function of us Horologists, and this is exactly what we did.”

Later I would learn what this puzzling terminology entailed.

“If you’ll pardon the indelicate question, Marinus,” Claudette-Holokai’s fingers traced her string of pearls, “when were you born?”

“640 A.D.,” I answered, a little drunk on the novelty of sharing the truth about myself. “I was Sammarinese in my first life. I was the son of a falconer.”

Holokai gripped her armchair as if hurtling forward at an incredible speed. “You’re more than twice my age, Marinus! I don’t have an exact birth year, or place. Probably Tahiti, possibly the Marquesas, I’d know if I went back, but I don’t care to. It was a horrible death. My second self was a Muhammadan slave boy in the house of a Jewish silversmith, in Portugal. King Joгo died while I was there, tethering my stay to the fixed pole of 1433. Xi Lo, however …”

Clouds of aromatic cigar smoke hung at various levels.

“I was first born at the end of the Zhou Dynasty,” said the man I’d been calling Mr. Davydov, “on a boat in the Yellow River delta. My father was a mercenary. The date would have been around 300 A.D. Fifty lifetimes ago, now, or more. I notice you appear to understand this language without difficulty, Miss Koskov, yes?”

Only as I nodded did I realize he was speaking in Chinese.

“I’ve had four Chinese lives.” I pressed my rusted Mandarin back into service. “My last was in the middle years of the Ming, the 1500s. I was a woman in Kunming then. An herbalist.”

“Your Chinese sounds more modern than that,” said Xi Lo.

“In my last life I lived on the Dutch Factory in Nagasaki, and practiced with some Chinese merchants.”

Xi Lo nodded at an accelerating pace, before declaring in Russian, “God’s blood! Marinus—the doctor, on Dejima. Big man, red face, white hair, Dutch, an irascible know-it-all. You were there when HMS Phoebusblasted the place to matchwood.”

I experienced a feeling akin to vertigo. “You were there?”

“I watched it happen. From the magistrate’s pavilion.”

“But—who wereyou? Or who were you ‘in’?”

“I had several hosts, though no Dutchmen, or I might have known you for an Atemporal, and saved Klara Koskov a world of bother. You Dutch were marooned by the fall of Batavia, you’ll recall, so my route in and out of Japan was via the Chinese trading junks. Magistrate Shiroyama was my host for some weeks.”

“I visited the magistrate several times. There was a big, buried scandal around his death. But what took you to Nagasaki?”

“A winding tale,” said Xi Lo, “involving a colleague, Фshima, who was Japanese in his first life, and a nefarious abbot named Enomoto, who unearthed a pre-Shinto psychodecanter up in Kirishima.”

“Enomoto visited Dejima. His presence made my skin creep.”

“The wisdom of skin is underappreciated. I used an Act of Suasion to persuade Shiroyama to end Enomoto’s reign. Poison. Regrettably, it cost the magistrate his life, but such was the arithmetic of sacrifice. My turn will come, one day.”

Jasper the dog took advantage of Vasilisa’s immobility to jump onto her lap, a liberty that my foster mother never granted.

I asked, “What’s ‘suasion’? Is it like a ‘hiatus’?”

“Both are Acts of Psychosoterica,” said Holokai-in-Claudette. “Where an Act of Hiatus freezes, an Act of Suasion forces. I presume your only present means of improving the lots of your lowerborn lives,” she indicated the Koskovs’ warm but humble parlor, “is by acquiring patrons, patronesses, and such?”

“Yes. And the accrued knowledge of my lifetimes. I gravitate towards medicine. For my female selves, it’s one of the few ways up.”

Galina was still chopping vegetables in the kitchen.

“Let us teach you shortcuts, Marinus.” Xi Lo leaned forward, his fingers drumming his cane. “Let us show you new worlds.”

· · ·

“SOMEONE’S MILES AWAY.” Unalaq leans on the door frame, holding a mug emblazoned with the logo of Metallica, the death-defying heavy-metal group. “The mug? A gift from Inez’s kid brother. Two updates: L’Ohkna’s paid for seven days on Holly’s hotel room; and Holly was beginning to stir, so I hiatused her until you’re ready.”

“Seven days.” I put the felt cover over the piano keys. “I wonder where we’ll be in seven days. To work, then, before Holly’s snatched from under my nose again.”

“Фshima said you’d be flagellating yourself.”

“He’s not up and about already, is he? He didn’t go to bed last night, and he spent the morning being an action hero.”

“Sixty minutes’ shut-eye and he’s up and off like a cocaine bunny. He’s eating Nutella with a spoon, straight from the jar. I can’t watch.”

“Where’s Inez? She shouldn’t leave the apartment.”

“She’s helping Toby, the bookshop owner. Our shield covers the shop, but I’ve warned her not to go further afield. She won’t.”

“What must she think of all this insanity and danger?”

“Inez grew up in Oakland, California. That gave her a grounding in the basics. C’mon. Let’s go Esther-hunting.” So I follow her downstairs to the spare room, where Holly is lying hiatused on a sofa bed. Waking her up seems cruel. Фshima appears from the library. “Sweet tinkling, Marinus.” He mimes piano fingers.

“I’ll pass my hat around later.” I sit down next to Holly and take her hand, pressing my middle finger against the chakra on her palm.

I ask my colleagues, “Is everyone ready?”

HOLLY JERKS UPRIGHT, as if her torso is spring-loaded, and struggles to make sense of a present perfect of homicidal policemen, of my Act of Hiatus, of Фshima, Unalaq, and me, and of this strange room. She notices she’s digging her nails into my wrist. “Sorry.”

“It’s perfectly all right, Ms. Sykes. How’s your head?”

“Scrambled eggs. What part of it was real?”

“All of it, I’m afraid. Our enemy took you. I’m sorry.”

Holly doesn’t know what to make of this. “Where am I?”

“154 West Tenth Street,” says Unalaq. “My apartment, mine and my partner’s. I’m Unalaq Swinton. And it’s two o’clock in the afternoon, on the same day. We figured you needed a little sleep.”

“Oh.” Holly looks at this new character. “Nice to meet you.”

Unalaq sips her coffee. “The honor’s all mine, Ms. Sykes. Would you like some caffeine? Any other mild stimulant?”

“Are you like … Marinus and the—the other one, that …?”

“Arkady? Yes, though I’m younger. This is only my fifth life.”

Unalaq’s sentence reminds Holly of the world she’s fallen into. “Marinus, those cops … they … I think they wanted to kill.”

“Hired assassins,” states Фshima. “Real flesh-and-blood people whose job is not to fix teeth or sell real estate or teach math but to murder. I made them shoot each other before they shot you.”

Holly swallows. “Who are you? If it’s not rude …”

Фshima’s mildly amused. “I’m Фshima. Yes, I’m another Horologist, too. Enjoying my eleventh life, since we’re counting.”

“But … youweren’t in the police car … were you?”

“In spirit, if not in body. For you, I was Фshima the Friendly Ghost. For your abductors, I was Фshima the Badass Sonofabitch. Won’t deny it, that felt good.” The city’s hiss and boom are smudged by steady drizzle. “Though our long cold War just got hotter.”

“Thank you, then, Mr. Фshima,” says Holly, “if that’s the appropri—” A barbed thought snags her: “ Aoife!Marinus—those police officers, theytheythey said Aoife’d been in an accident!”

I shake my head. “They lied. To lure you into the car.”

“But they know I’ve got a daughter! What if they hurt her?”

“Look, look, look. Look at this.” Unalaq passes her a slate. “Aoife’s blog. Today she found three shards of a Phoenician amphora and some cat bones. Posted forty-five minutes ago, at sixteen seventeen Greek time. She’s fine. You can message her, but don’t, don’t, refer to any of today’s events. That wouldrisk embroiling her.”

Holly reads her daughter’s entry and her panic subsides a notch. “But just ’cause those people haven’t hurt her yet, it doesn’t—”

“This week the Anchorites’ attention is focused on Manhattan,” says Фshima. “But to be safe, your daughter has a bodyguard. Roho’s one of us, too.” And one that the Second Mission can ill spare, Фshima subreminds me.

Again, Holly is all at sea. She tucks some loose strands of hair under her head-wrap. “Aoife’s on an archaeological dig, on a remote Greek island. How … I mean, why … No.” Holly looks for her shoes. “Look, I just want to go home.”

I break the brutal truth gently: “You’d get as far as the Empire Hotel, but you wouldn’t leave the building alive. I’m sorry.”

“Even if you slip through that net,” Фshima extends the brutal truth more bluntly, “the next time you used an ATM card, your device, your slate, an Anchorite would find you within a few minutes. Even without using those methods, unless you’re hidden by a Deep Stream cloak, they could get to you with a quantum totem.”

“But I live in the west of Ireland! That’s not gangster country.”

“You’d not be safe on the goddamn International Space Station, Ms. Sykes,” says Фshima. “And the Anchorites of the Chapel of the Dusk belong to a higher order of threat than gangsters.”

She looks at me. “So what must I do to be safe? Stay here forever?”

“I think,” I tell her, “you’ll only be safe if we win our War.”

“If we don’t win,” says Unalaq, “it’s over for all of us.”

Holly Sykes shuts her eyes, giving us one last chance to vanish and to return to her life as it was at Blithewood Cemetery before a slightly chubby African Canadian psychiatrist strolled into view.

Ten seconds later, we’re still here.

She sighs and tells Unalaq, “Tea, please. Splash of milk, no sugar.”

“ ‘HOROLOGY’?” REPEATS Holly in Unalaq’s kitchen. “Isn’t that clocks?”

“When Xi Lo founded our Horological Society,” I say, “the word meant ‘the study of the measurement of time.’ It was a sort of self-help group, you could say. Our founder was a London surgeon in the 1660s—he appears in Pepys’s diary, by the by—and acquired a house in Greenwich as a headquarters, a storage facility, and a noticeboard to help us stay connected down through time, from one self to the next.”

“In 1939,” says Unalaq, “we shifted to 119A—where you visited this morning—because of the German threat.”

“So Horology is a social club for you … Atemporals?”

“It is,” says Unalaq, “but Horology has a curative function, too.”

“We assassinate,” states Фshima, “carnivorous Atemporals—like the Anchorites—who consume the psychovoltaic souls of innocent people in order to fuel their own immortality. I thought Marinus told you this earlier.”

“We do give them a chance to mend their ways,” says Unalaq.

“But they never do,” says Фshima, “so we have to mend their ways for them, permanently.”

“They are serial killers,” I tell Holly. “They murder kids like Jacko, and teenagers like you were. Again and again and again. They don’t stop. Carnivores are addicts and their drug is artificial longevity.”

Holly asks, “And Hugo Lamb is one of these serial killers?”

“Yes. He’s sourced prey eleven times since … Switzerland.”

Holly swivels her eternity ring. “And Jacko was one of you?”

“Xi Lo founded Horology,” says Фshima. “Xi Lo led me to the Deep Stream. To psychosoterica. He was irreplaceable.”

Holly thinks of a small boy with whom she shared only eight Christmases. “How many of there are you?”

“Seven, definitely. Eight, possibly. Nine, hopefully.”

Holly frowns. “Quite a small-scale war, then, isn’t it?”

I think of Oscar Gomez’s wife. “Was there anything ‘small-scale’ about Jacko’s disappearance for the Sykes family? Eight is very few, but we were only ten when we inoculated you. We build networks. We have allies and friends.”

“And how many Carnivores are there?”

“We don’t know,” says Unalaq. “Hundreds, worldwide.”

“But whenever we find one,” Фshima inserts a meaningful pause, “there soon becomes one less.”

“The Anchorites endure, however,” I say. “The Anchorites are our enemy through time. Can we prevent all the Carnivores in the world from committing animacide? No. But whom we save, we save, and every one is a victory.”

Pigeons croon and huddle on Unalaq’s window boxes.

“Let’s say I believe you,” says Holly. “Why me? Why do these Anchorites want to—Christ, I can’t believe I’m saying this—want to kill me? And what am I to you?” She looks around the table. “Why do I matter in your War?”

Фshima and Unalaq look at me. “Because you said ‘Yes,’ forty years ago, to a woman named Esther Little, who was fishing off a rickety wooden pier jutting out over the Thames.”

Holly stares at me. “How can you possibly knowthat?”

“Esther told me about the encounter. That day, in 1984.”

“ Youwere in Gravesend? That Saturday Jacko went?”

“My body was. My soul was in Jacko’s skull, as Jacko lay in his bed in the Captain Marlow. Esther Little’s soul was there too, as was the soul of Holokai, another colleague. With Xi Lo’s soul, that made four Greeks hiding in the belly of the Trojan Horse. Miss Constantin appeared in the room, through the Aperture, and ushered Jacko up the Way of Stones into the Chapel of the Dusk.”

“The place the Blind Cathar built?” Holly’s voice is dry.

“The place the Blind Cathar built.” Good, she’d taken it in. “Jacko was Constantin’s bait. We’d poked her eye by inoculating you, and we gambled on her not being able to resist poking ours in return by grooming and abducting the saved sister’s brother. That part worked, and for the first time Horologists gained access to the oldest, hungriest, and best-guarded psychodecanter in existence. Before we could figure out a means of destroying the place, however, the Blind Cathar awoke. He summoned all the Anchorites and, well, it’s hard to describe a psychosoteric battle at close quarters …”

“Think of those tennis-ball firing machines, but loaded with hand grenades,” offers Фshima, “trapped in a shipping container, on a ship caught in a force-ten gale.”

“It was the worst day in Horology’s history,” I say.

“We killed five Anchorites,” says Фshima, “but they killed Xi Lo and Holokai. Killed-killed.”

“Didn’t they just get … resurrected?” asked Holly.

“If we die in the Dusk,” I explain, “we die. Terms and conditions. Somehow the Dusk prevents resurrection. I survived because Esther Little fought her way to and fled down the Way of Stones with my soul enwrapped in hers. Alone, I would have perished, but even in Esther’s safekeeping I suffered grievous damage, as did Esther. She opened the Aperture very near where you were, Holly, in the garden of a certain bungalow near the Isle of Sheppey.”

“I’m guessing the location was no accident?” asks Holly.

“It was not. While Esther’s soul and mine were reraveling, however, the Third Anchorite, one Joseph Rhоmes, arrived on the scene. He had followed our tracks. He slew Heidi Cross and Ian Fairweather for the hell of it, and was about to kill you, too, when I reraveled myself enough to animate Fairweather. Rhоmes kineticked a weapon into my head, and I died. Forty-nine days later I was resurrected in this body, in a broken-down ambulance in one of Detroit’s more feral zip codes. For a long time I assumed Rhоmes had killed you in the bungalow, and that Esther’s soul had been too badly damaged to reravel. But when I next made contact with 119A, Arkady—in his last self, not the self you met earlier—told me that you hadn’t died. Instead, Joseph Rhоmes’s body had been found at the crime scene.”

“Only a psychosoteric could have killed Joseph Rhоmes,” says Фshima. “Rhоmes followed the Shaded Way for seventeen decades.”

Holly understands. “So you think it was Esther Little?”

Unalaq says, “It’s the least implausible explanation.”

“But Esther Little was a … sweet old bat who gave me tea.”

“Yes,” snorts Фshima, “and I’m a sweet old boy who rides around all day on my senior citizen’s bus pass.”

“Why don’t I remember any of this?” says Holly. “And where did Esther Little go afterkilling this Rhоmes man?”

“The first question’s simpler,” says Unalaq. “Any psychosoteric can redact memories. It takes skill to do it with precision, but Esther had that skill. She could have done it on her way in.”

Unconsciously, Holly grips the table. “On her way in—to where?”

“Into your parallax of memories,” I say. “To the asylum you offered her. Esther’s soul was battered in the Chapel of the Dusk, flamed as she fought our way out down the Way of Stones, and drained to the last psychovolt by killing Joseph Rhоmes.”

“Her soul would have needed years to reravel,” says Unalaq. “Years when Esther was as vulnerable to attack as someone in a coma.”

“I … sort of get it.” Holly’s chair creaks. “Esther Little ‘in-gressed’ me, got me away from the crime scene, wiped my memories of what happened … Okay. But where did she go aftershe … recovered?”

Фshima, Unalaq, and I all look at Holly’s head.

Holly frowns, then understands. “You’re bloody joking.”

BY SEVEN O’CLOCK, twilight is draping the attic in blues, grays, and blacks. The little lamp on the piano glows daffodil yellow. Four storys below us, I see the manager of the bookshop bidding a staff member good night. He then walks off arm in arm with a petite lady. The couple make an old-fashioned sight under the mist-haloed solars of West Tenth Street. I draw the curtains on the drizzlestreaked bulletproof glass. Фshima, Unalaq, and I spent the afternoon debriefing Holly further on Horology and our War with the Anchorites, and eating Inez’s pancakes. Going outside would have been a needless risk after this morning’s near disaster, and we’ll avoid 119A until our rendezvous with D’Arnoq on Friday. Arkady and the Deep Stream cloak will keep the place safe. On the evening news the “Police Impostor Fifth Avenue Shootout” was a lead story, with reporters speculating that the dead men were bank robbers who’d had a fatal argument prior to their heist. The national networks haven’t run with the story, due to yesterday’s gun massacre at Beck Creek, Texas, the reignited Senkaku/Diaoyu standoff between China and Japan, and Justin Bieber’s fifth divorce. The Anchorites will know Brzycki was killed by psychosoteric intervention, but how it affects any plans they have for our Second Mission, I cannot guess. I’ve heard nothing from our defector, Elijah D’Arnoq. I hear Unalaq and Holly’s feet on the creaky stairs, and they appear in the doorway.

“You have a psychiatrist’s couch,” says Holly.

“Dr. Marinus will see you now,” I say. “Again. Ready?”

Holly unslippers her feet, and lies back. “I’ve got over half a century of memories stored away, right?”

I roll up the sleeves of my blouse. “A finite infinity, yes.”

“How do you know where to look for Esther Little?”

“I was sent a clue via a cabdriver in Poughkeepsie,” I say.

Unalaq puts a cushion under Holly’s head. “Relax.”

“Marinus?” Holly flinches. “Will you see everythingI ever did?”

“That’s how scansion works. But I’m a psychiatrist from the seventh century, remember. There’s not much left that I haven’t seen.”

Holly’s unsure what to do with her hands. “Do I stay conscious?”

“I can hiatus you while I scansion you, if you wish.”

“Uh … No need. Yes. I dunno. You decide.”

“Very well. Tell me about your house, near Bantry.”

“O– kay. Dooneen Cottage was originally my great-aunt Eilнsh’s cottage. It’s on the Sheep’s Head Peninsula, this rocky finger sticking out into the Atlantic. There’s a drop to a cove at the end of the garden, and a path going down to the pier and …”

AS I INGRESS, I hiatus her. It’s kinder, somehow. Holly’s present-perfect memory, I notice, is dominated by today’s bizarre events, but older memories soon billow around my passing soul like windblown sheets on a washing line. Here’s Holly catching a taxi from the Empire Hotel early this morning. Meeting me at the Santorini Cafй, and at Blithewood. Landing in Boston last week. I go further back, back to Holly’s pluperfect memory. Holly painting in her studio, spreading seaweed on her potato patch, watching TV with Aoife and Aoife’s boyfriend. Cats. Storm petrels. Jump leads. Mixing mincemeat at Christmas. Kath Sykes’s funeral in Broadstairs. Deeper, faster, like rewind on an old-style DVD, showing one frame every eight, sixteen, thirty-two, sixty-four … Too fast. Slow down. Too slow, this is like searching for an earring dropped somewhere in Wyoming, I must take care. Here’s a vivid memory of Dr. Tom Ballantyne: “I sent off three samples to three different labs. Remissions are fickle, yes, but for now, you’re clear. I won’t pretend to understand it—but congratulations.” Deeper, further. Memories of Holly meeting Crispin Hershey in Reykjavik, in Shanghai, on Rottnest Island. They loved each other, I see, but both only half guessed it. Holly’s first U.S. book tour for The Radio People. Holly’s office at the homeless center. Her Welsh friend and colleague Gwyn. Aoife’s face when Holly tells her that Ed died in a missile strike. Olive Sun’s voice on the phone, an hour earlier. Happier days. Watching Aoife perform in The Wizard of Ozwhile holding Ed’s hand in the darkness. Psychology lectures with the Open University. Look, a glimpse of Hugo Lamb … Stop. Their night in a room in a Swiss ski town, which is none of my business, but what muffled, baffled joy shines in the young man’s eyes. He loved her, too. But the Anchorites came knocking. Fateful or fated? Scripted, Counterscripted? No time. Hurry. Deeper. A vineyard in France. A slategray sea—is the asylum here? There’s no sign of the freighter. Too far or not far enough? Look closely. The wind must be squally and the engines churning. Stop. No time, no noise. Passengers become photographs of themselves. Gulls, balancing gravity and the battering wind. A squaddie’s tossed away his cigarette, it hangs there, threads of smoke, vapor trailing … This is Holly’s first Channel crossing, back before the tunnel was built. Back further, a year or two or three … An iced “17” on a birthday cake … Further. An abortionist’s clinic in the shadow of Wembley Stadium, a young man on a Norton motorbike outside. Slowly now … A slope of gray months, after Jacko’s disappearance. Picking strawberries …