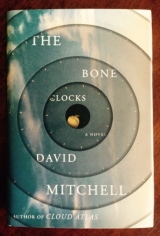

Текст книги "The Bone Clocks"

Автор книги: David Mitchell

Жанры:

Классическое фэнтези

,сообщить о нарушении

Текущая страница: 24 (всего у книги 40 страниц)

“It’s a wren,” said Mum, turning to go.

THE SUN’S SUNK behind the high lip of Бsbyrgi, so the greens are stewing to grays and browns. Leaves and twigs are losing threedimensionality. When I remember my mother, am I remembering her, or just memories of her? The latter, I suspect. The glass of dusk is filling by the minute, and I don’t really know where I left my Mitsubishi. I feel like Wells’s time traveler separated from his time machine. Should I be getting alarmed? What’s the worst that could happen to me? Well, I may neverfind my way out, and die of exposure. Ewan Rice will write my obituary for The Guardian. Or would he? At the housewarming/meet-Carmen party I threw last autumn Ewan almost went out of his way to emphasize his alpha literary male status: dinner with Stephen Spielberg on his last trip to L.A.; fifty thousand dollars for a lecture at Columbia; an invitation to judge the Pulitzer—“I’ll see if I can fit it in, I’m so damn busy.” So maybe not. My sister Phoebe’ll miss me, even if the hatchets we’ve buried in the past are not buried very deep. Carmen would be distraught, I think. She might blame herself. Holly, bless her, would organize the logistics from this end. They’d both steal the show at my funeral. Hyena Hal will know about my death before I do, but will he miss me? As a client, I’m now a conspicuous underperformer. Zoл? Zoл won’t notice until the alimony account runs dry, and the girls would sob their hearts out. Anaпs might, anyway.

This is ridiculous! It’s a medium-sized wood, not a vast forest. There were some camper vans right by the car park. Why not just yell, “Help!” Because I’m a guy, I’m Crispin Hershey, the Wild Child of British Letters. I just can’t. There’s a mossy boulder that looks like the head of a troll, thrusting up through a thin ceiling of earth …

· · ·

… by some trick of this northern light, a narrow segment of my 360-degree woodland view—it includes the mossy boulder and the X made by two leaning trunks behind—wavers and shimmers, like a sheet blown in a breeze, a breeze that isn’t even there …

No: Look! A handappears in the air, and pulls the sheet aside, a hand whose owner now steps out of the slitted air. Like a conjuring trick—a really, really astonishing one. A blond young man, dressed in jacket and jeans, has materialized here, in the middle of this wood. Midtwenties and with model-good looks. I watch, astonished: Am I … actually seeing a ghost? A twig cracks under his desert boot. No ghost and no materializing, you idiot; my “ghost” is just a tourist, like me. From the camper vans, like as not. Probably he just took a dump. Blame the twilight; blame another day spent in my own company. I tell him, “Good evening.”

“Good evening, Mr. Hershey.” His English sounds more expensively schooled British than sibilant Icelandic.

I’m gratified, I admit. “My. Odd place to be recognized.”

He takes a few paces until we’re at arm’s length. He looks pleased. “I’m an admirer. My name’s Hugo Lamb.” Then he smiles with charisma and warmth, as if I’m a trusted friend he’s known for years. For my part, I feel an unwanted craving for his approval.

“Nice, uh, to meet you then, Hugo. Look, this is all a bit embarrassing, but I’ve gone and mislaid the car park …”

He nods and his face turns thoughtful again. “Бsbyrgi plays these tricks on everybody, Mr. Hershey.”

“Could you point me in the right direction, then?”

“I could. I will. But, first, I have a few questions.”

I take a step back. “You mean … about my books?”

“No, about Holly Sykes. You’ve become close, we see.”

With dismay I realize this Hugo’s one of Holly’s weirdos. Then with anger, as I realize, no, he’s a tabloid “reporter”; she’s had some bother with the telephoto lens gang at her new house in Rye. “I’d loveto give you the lowdown on me ’n’ Hol,” I sneer at Handsome Pants, “but here’s the thing, sunshine: It’s none of your fuckingbusiness.”

Hugo Lamb is utterly unriled. “Ah, but you’re wrong. Holly Sykes’s business is very much our concern.”

I start walking off, backwards, watchfully. “Whatever. Goodbye.”

“You’ll need my assistance to get out of Бsbyrgi,” says the youth.

“Your assistance will fit neatly up your small intestine. Holly’s a private person, and so am I, and I’ll find my own way ba—”

Hugo Lamb has made a peculiar gesture with his hand, and my body is lifted ten feet into the air and squeezed in an invisible giant’s fist: My ribs crunch; the nerves in my spine crackle and the agony is indescribable; begging for mercy or screaming is impossible, and so is enduring this torture for a second longer, but seconds pass, I think they’re seconds, they could be days, until I’m thrown, not dropped, onto the forest floor.

My face is pressed into leaf mold. I’m grunting, quivering, and whimpering even as the agony fades. I look up. Hugo Lamb’s face is that of a boy dismembering a daddy longlegs; mild interest and gleeful malevolence. A Taser might explain the incapacitating pain, but what about the ten-feet-off-the-ground bit? Something atavistic snuffs my curiosity now, however; I need to get away from him. I’ve pissed myself but I don’t even care. My feet don’t work, and a far-off voice might be roaring at me, “You’ll never walk alone again,” but I won’t listen, I can’t, I daren’t. I crawl backwards, then pull myself upright, against a big tree stump. Hugo Lamb makes another gesture and my legs fold under me. There’s no pain this time. Worse, almost, there’s nothing. From my waist down, all sensation has gone. I touch my thigh. My fingers register my thigh but my thigh registers nothing. Hugo Lamb walks over—I cower—and perches on the tree stump. “Legs do come in handy,” he says. “Do you want yours back?”

My voice is shaky as heck: “What areyou?”

“Dangerous, as you see. You’ll recognize these two cuties.” He removes a little square from his pocket and shows me the passport photo of me, Anaпs, and Juno that I lost a few days ago. “Answer my questions honestly, and they’ll have as decent a chance of a long and happy life as any child at Outremont Lycйe.”

This good-looking youth is the stuff of a bad acid trip. Obviously he stole the photo, but when and how, I cannot guess. I nod.

“Let’s begin. Who is most precious to Holly Sykes?”

“Her daughter,” I say hoarsely. “Aoife. That’s no secret.”

“Good. Are you and Holly lovers?”

“No. No. We’re just friends. Really.”

“With a woman? Is that typical for you, Mr. Hershey?”

“I guess not, but it’s how it is with Holly.”

“Has Holly ever mentioned Esther Little?”

I swallow and shake my head. “No.”

“Think very carefully: Esther Little.”

I think, or try to. “I don’t know the name. I swear.” I can hear how petrified I sound.

“What has Holly told you about her cognitive gifts?”

“Only what’s in her book. In The Radio People.”

“Yes, a real page-turner. Have you witnessed her channeling a voice?” Hugo Lamb notices my hesitation. “Don’t make me count down from five, like some hokey interrogator in a third-rate movie, before I fry you. Your fans know how you detest clichй.”

The hollow deepens as the trees lean over. “Two years ago, on Rottnest Island, near Perth, Holly fainted, and a weird voice came out of her mouth. I thought it was epilepsy, but she said how the prisoners had suffered, and then … she spoke in Aborigine … and—that’s all. She hit her head. Then she was back.”

Hugo Lamb tap-tap-taps the photo. Some part of me still able to analyze notices that although his face is young something about his eyes and intentness is much older. “What about the Dusk Chapel?”

“The what chapel?”

“Or the Anchorites? Or the Blind Cathar? Or Black Wine?”

“I never heard of any of those things. I swear.”

Tap-tap-tap goes Hugo Lamb’s finger on the photo of me and the girls. “What does Horology mean to you?”

This feels like some demonic pub quiz: “Horology? The study of the measurement of time. Or old clocks.”

He leans over me; I feel like a microbe on a slide. “Tell me what you know about Marinus.”

Wretched as a snitch and hopeful this will save my daughters, I tell my eerie interrogator that Marinus was a child psychiatrist at Gravesend Hospital. “He’s mentioned in Holly’s book as well.”

“Has she met Marinus during the time you’ve known her?”

I shake my head. “He’ll be ancient now. If he’s still alive.”

Is a woman laughing on the outer edge of my hearing?

“What is,” Hugo Lamb watches me carefully, “the Star of Riga?”

“The capital of Estonia. No. Latvia. Or Lithuania. I’m not sure. One of the Baltic states, anyway. I’m sorry.”

Hugo Lamb considers me. “We’re finished.”

“I—I told you the truth. Completely. Don’t hurt my kids.”

He swings off the mossy boulder and walks away, telling me, “If their daddy’s an honest man, Juno and Anaпs have nothing to fear.”

“You—you’re—you’re letting me go?” I touch my legs. They’re still dead. “Hey! My legs! Please!”

“Knew I’d forgotten something.” Hugo Lamb turns around. “By the by, Mr. Hershey, the critics’ treatment of Echo Must Diewas egregious. But, hey, you shafted Richard Cheeseman royallyin return, didn’t you?” Lamb’s smile is puckered and conspiratorial. “He’ll never guess, unless someone plants the idea in his head. Sorry about your trousers; the car park is left at the last fork. That much you’ll remember. Everything else I’ll redact. Ready?” His eyes fixing mine, Hugo Lamb twists the air into threads between his forefingers and thumbs, then pulls tight …

… a mossy boulder, big as a troll’s head, on its side and brooding over an ancient wrong. I’m sitting on the ground with no memory of tripping, though I must have done; I’m aching all over. How the sodding hell did I get down here? A mini-stroke? Magicked by the elves of Бsbyrgi? I must have … what? Sat down for a breather, then nodded off. A breeze passes, the trees shiver, and a yellow leaf loop-the-loops, landing by a fluke of air currents on my palm. Look at that. For the second time today, I think of Mr. Chimes the conjuror. Not far away, a woman’s laughing. The campsite’s near. I get up—and notice a big cold stain down my thigh. Oh. Okay. The Wild Child of British Letters has suffered a somnambulant urethral mishap. Lucky there’s no Piccadilly Reviewdiarist around. I’m only fifty-three—surely still a bit young for incontinence pads? It’s all chilly and clammy, like it happened a couple of minutes ago. Thank God I’m so close to the parking area, clean boxers, and trousers. Back to the fork, then turn left. Let us hurry, dear reader. It’ll be night before you know it.

September 23, 2019

IT LOOKS LIKE HALLDУR LAXNESS splurged most of the Nobel dosh on Gljъfrasteinn, his white, blockist 1950s home halfway up a mist-smudged vale outside Reykjavik. From the outside it reminds me of a 1970s squash club in the Home Counties. A river tumbles by and on through the mostly treeless autumn. Parked in the drive is a cream Jag identical to the one Dad had. I buy my ticket from a friendly knitter with a cushy job and walk over to the house proper, where I put on my audio guide as directed. My digital spirit guide tells me about the paintings, the modernist lamps and clocks, the low Swedish furniture, a German piano, parquet floors, cherry-wood fittings, leather upholstery. Gljъfrasteinn is a bubble in time, as is right and proper for a writer’s museum. Climbing the stairs, I consider the prospect of a Crispin Hershey Museum. The obvious location is the old family home in Pembridge Place, where I lived both as a boy and as a father. The snag is, the dear old place was gutted by builders, the week after I handed over the keys, subdivided into six flats and sold to Russian, Chinese, and Saudi investors. Reacquisition, reunification, and restoration would be a multilingual and ruinously expensive prospect, so my current address on East Heath Lane, Hampstead, is the likeliest candidate—assuming Hyena Hal can persuade Bleecker Yard’s and Erebus’s lawyers not to whisk it away, of course. I imagine reverent visitors stroking my varnished handrails and whispering in awed tones, “My God, that’s thelaptop he wrote his triumphant Iceland novel on!” The gift shop could be squeezed into the downstairs bog: Crispin Hershey key fobs, Desiccated Embryomouse mats, and glow-in-the-dark figurines. People buy such bollocks at museums. They don’t know what else to do once they’re there.

Upstairs, the digital guide mentions in passing that Mr. and Mrs. Laxness occupied different bedrooms. So I see. Strikes a sodding chord. Laxness’s typewriter sits on his desk—or, more accurately, his wife’s typewriter, as she typed up his handwritten manuscripts. I wrote my debut novel on a typewriter, but Wanda in Oilswas composed on a secondhand Brittan PC handed down by Dad as a birthday present, and it’s been ever-lighter, ever-trustier laptops ever since. For most digital-age writers, writing isrewriting. We grope, cut, block, paste, and twitch, panning for gold onscreen by deleting bucketloads of crap. Our analog ancestors had to polish every line mentally before hammering it out mechanically. Rewrites cost them months, meters of ink ribbon, and pints of Tippex. Poor sods.

On the other hand, if digital technology is so superior a midwife of the novel, where are this century’s masterpieces? I enter a small library where Laxness seems to have kept his overflow, and bend my neck to graze upon the titles. Plenty of hardbacks in Icelandic, Danish, I guess, German, English … and sodding hell —Desiccated Embryos!

Hang on, this is the 2001 edition …

… and Laxness died in 1998. Right.

Well, a kind gesture of the Hidden Folk.

GOING DOWNSTAIRS, I make way for a dozen teenagers trooping up. Where do Juno and Anaпs go on their school trips in Montreal? Not knowing saddens me. What a long-distance, part-time father I am. These twenty-first-century children of Iceland are plugged into headsets but still exude that Nordic confidence and sense of wellbeing, even the two African Icelanders and a girl in a Muslim headdress. All have a 2 in front of their birth year and need barely scroll down an inch when finding it on an online form. They carry a fragrance of hair conditioner and fabric conditioner. Their consciences are as undented as cars in a dealership showroom, and all are bound for the world’s center stage, where they’ll challenge, outperform, and patronize us old farts at our retirement parties, as we did when we looked that beautiful. Their teacher brings up the rear and smiles his thanks at me, and as he passes, a rather fine mirror is revealed on the Laxness stairway. From its deep square well of grays peers out a haggard look-alike of Anthony Hershey. Look at that. My metamorphosis into Dad is complete. Did some evil spirit at Бsbyrgi suck out the last of my youth? My hair’s thinner, my skin’s tired, my eyes bloodshot; my neck’s going all saggy and turkey-like … I summon a Tagore quote, for consolation: “Youth is a horse, and maturity a charioteer.” Dad’s aging lips twitch into a sneer and speak: “I see no charioteer. I see a sociology lecturer at a third-rate university who just learned that his department’s being axed because nobody except future sociology lecturers studies sociology anymore. You’re a joke, boy. Do you hear me? A joke.”

My prime of life is going, going, gone …

TRUDGING DOWN TO the Mitsubishi waiting in Gljъfrasteinn’s small car park, I check the time on my phone—and find a message from Carmen Salvat. It is not the message I might have wished to receive.

hello crispin pIs can we talk? x yr friend C

I huff. My soul still aches from being dumped, but I’m handling it. I don’t want to have to unhandle it, or un-unhandle it. We ingest our emotions, and grief for a lost relationship is not what I want to ingest. Carmen’s “yr friend” is code for “We won’t be getting back together”and “hello” instead of “hi” is the textual equivalent of a chilly air-kiss rather than a cheek-to-cheek contact kiss:

maybe not for a while, if that’s ok. It still hurts and I’m bored of the pain. No offense meant and mind yourself. C.

After pressing send I wish I’d taken more care to sound less petulant and/or self-pitying. Suddenly the river’s annoyingly clattery: How did Laxness get any work done, for buggery’s sake? The gathering clouds are lead-lined gray, not Zen gray. The aging day’s intersecting meanings form a crossword that defeats me, not inspires me, like it used to. I’m not as good a writer as Halldуr Laxness. I’m not even as good a writer as the younger Crispin Hershey. I’m just as shit and uncommitted a dad as Dad, only his films will survive longer than my overregarded novels. My clothes are crumpled. My lecture’s at seven-thirty. My heart is still crusty with emotional scabs, and I don’t want them pulled off by a Spanish ex-partner.

No. We can’t talk. I switch off my phone.

“THE NAME OF my lecture is On Never Not Thinking About Iceland.” It’s a decent turnout at the House of Literature, but half of the two hundred attendees are here because the Bonny Prince Billy concert was sold out, and a portion of the silver-haired contingent showed up because they love Dad’s films. The only faces I know are Holly’s, Aoife’s, and Aoife’s boyfriend Цrvar’s, sending me friendly vibes from the front row. “This car crash of a title,” I continue, “is derived from an apocryphal remark of W. H. Auden’s, spoken here in Reykjavik, for all I know on this very podium, to your parents or grandparents. Auden said that while he hadn’t lived his life thinking about Iceland hourly or even daily, ‘There was never a time when I wasn’tthinking about Iceland.’ What a delicious, cryptic statement. ‘Never not thinking about Iceland’? Why not just say, ‘Always thinking about Iceland’? Because, of course, double negatives are truth smugglers, are censor outwitters. This evening I’d like to hold Auden’s double negative”—I raise my left hand, palm up—“alongside this double-headed fact about writing,” right hand, palm up. “Namely, that in order to write, you need a pen and a place, or a study and a typewriter, or a laptop and a Starbucks—it doesn’t matter, because the pen and the place are symbols. Symbols for means and tradition. A poet uses a pen to write but, of course, the poet doesn’t makethe pen. He or she buys, borrows, inherits, steals, or otherwise acquires the pen from elsewhere. Similarly, a poet inhabits a poetic tradition to write within, but no poet can single-handedly create that tradition. Even if a poet sets out to invent a new poetics, he or she can only react against what’s already there. There’s no Johnny Rotten without the Bee Gees.” Not a flicker from my Icelandic audience; maybe the Sex Pistols never made it this far north. Holly smiles for me, and I worry at how thin and drawn she’s looking. “Returning to Auden,” I continue, “and his ‘never not.’ What I take from his remark is this: If you’re writing fiction or poetry in a European language, that pen in your hand was, once upon a time, a goose quill held by an Icelander. Like it or not, know it or not, it doesn’t matter. If you seek to represent the beauty, truth, and pain of the world in prose, if you seek to deepen character via dialogue and action, if you seek to unite the personal, the past, and the political in fiction, then you’re in pursuit of the same aims sought by the authors of the Icelandic sagas, right here, seven, eight, nine hundred years ago. I assert that the author of Njal’s Sagadeploys the very same narrative tricks used later by Dante and Chaucer, Shakespeare and Moliиre, Victor Hugo and Dickens, Halldуr Laxness and Virginia Woolf, Alice Munro and Ewan Rice. What tricks? Psychological complexity, character development, the killer line to end a scene, villains blotched with virtue, heroic characters speckled with villainy, foreshadow and backflash, artful misdirection. Now, I’m not saying that writers in antiquity were ignorant of all of these tricks but,” here I put my balls and Auden’s on the block, “in the sagas of Iceland, for the first time in Western culture, we find proto-novelists at work. Half a millennium avant le parole, the sagas are the world’s first novels.”

Either the audience is listening, or else they’re merely snoozing with eyes open. I turn over my notes.

“So much for the pen. Now for the place. From the vantage point of continental Europeans, Iceland is, of course, a mostly treeless, mostly cold oval rock where a third of a million souls eke out a living. Within my own lifetime Iceland has made the front pages exactly four times: the Cod Wars of the 1970s; the setting for Reagan’s and Gorbachev’s arms-control talks; an early casualty of the 2008 crash; and as the source of a volcanic ash cloud that disabled European aviation in 2010. Blocs, however, whether geometric or political, are defined by their outer edges. Just as Orientalism seduces the imagination of a certain type of Westerner, to a certain type of southerner, Iceland exerts a gravitational force far in excess of its landmass and cultural import. Pytheas, the Greek cartographer who lived around 300 B.C. in a sunbaked land on the far side of the ancient world, he felt this gravity, and put you on his map: Ultima Thule. The Irish Christian hermits who cast themselves onto the sea in coracles, they felt this pull. Tenth-century refugees from the civil war in Norway, they felt it too. It was their grandsons who wrote the sagas. Sir Joseph Banks, enough Victorian scholars to sink a longship, Jules Verne, even Hermann Gцring’s brother, who was spotted by Auden and MacNeice here in 1937, they all felt the pull of the north, of your north, and all of them, Ibelieve, like Auden—were never not thinking about Iceland.”

The UFO-shaped lights of the House of Literature blink on.

“Writers don’t write in a void. We work in a physical space, a room, ideally in a house like Laxness’s Gljъfrasteinn, but we also write within an imaginative space. Amid boxes, crates, shelves, and cabinets full of … junk, treasure, both cultural—nursery rhymes, mythologies, histories, what Tolkien called ‘the compost heap’; and also personal stuff—childhood TV, homegrown cosmologies, stories we hear first from our parents, or later from our children—and, crucially, maps. Mental maps. Maps with edges. And for Auden, for so many of us, it’s the edges of the maps that fascinate …”

HOLLY’S BEEN RENTING her apartment since June, but she’ll be moving back to Rye in a couple of weeks so it’s minimally furnished, uncluttered, and neat, all walnut floors and cream walls, with a fine view of Reykjavik’s jumbled roofs, sloping down to the inky bay. Streetlights punctuate the northern twilight as color drains away, and a trio of cruise liners glitters in the harbor, like three floating Las Vegases. Over the bay, a long, whale-shaped mountain dominates the skyline, or would, if the clouds weren’t so low. Цrvar says it’s called Mount Esja, but admits he’s never climbed it because it’s right there, on the doorstep. I biff away an intense wish to live here, intense, perhaps, because of its utter lack of realism: I don’t think I’d survive a single winter of these three-hour days. Holly, Aoife, Цrvar, and I eat a veggie moussaka and polish off a couple of bottles of wine. They ask me about my week on the road. Aoife talks about her summer’s dig on a tenth-century settlement near Eglisstaрir, and nudges the amiable but quiet Цrvar into discussing his work on the genetic database that has mapped the entire Icelandic population: “Eighty-plus women were found to have Native American DNA,” he tells me. “This proves pretty conclusively that the Vinland Sagas are based on historical truth, not just wishful thinking. Lots of Irish DNA on the women’s side, too.” Aoife describes an app that can tell every living Icelander if and how closely related they are to every other living Icelander. “They’ve needed it for years,” she pats Цrvar’s hand on the table, “to avoid those awkward, morning-after in-Thor’s-name-did-I-just-shag-my-cousin?moments. Right, Цrvar?” The poor lad half blushes and mumbles about a gig starting somewhere. Everyone in Reykjavik under thirty years old, Aoife says, is in at least one band. They get up to go, and as I’m leaving first thing in the morning they both wish me bon voyage. I get a niece’s hug from Aoife and a firm handshake from Цrvar, who only now remembers that he brought Desiccated Embryosfor me to sign. While Цrvar laces up his boots, I try to think of something witty to mark the occasion, but nothing witty arrives.

To Цrvar, from Crispin, with best regards.

I’ve striven to be witty since Wanda in Oils.

Letting it go feels so sodding liberating.

· · ·

I STIR, STIR, stir until the mint leaves are bright green minnows in a whirlpool. “The nail in the coffin of Carmen and me,” I tell Holly, “was Venice. If I never see the place again, I’ll die happy.”

Holly looks puzzled. “I found it rather romantic.”

“That’s the trouble. All that beauty: in– sodding-sufferable. Ewan Rice calls Venice the Capital of Divorce—and set one of his best books there. About divorce. Venice is humanity at its ripped-off, ripping-off worst … I made this smart-arse remark about a rip-off umbrella Carmen bought—really, the sort of thing I say twenty times a day—but instead of batting it away, she had this look … like, ‘Remind me, why am I spending the last of my youth on this whingeing old man?’She walked off across Saint Mark’s Square. Alone, of course.”

“Well,” Holly says neutrally, “we all have off days …”

“Bit of a Joycean epiphany, looking back. I don’t blame her. Either for finding me irritating or for dumping me. When she’s my age now, I’ll be sixty-sodding– eight, Holly! Love may be blind, but cohabitation comes with all the latest X-ray gizmos. So we spent the next day moseying around museums on our own, and when we said goodbye at Venice airport, the last thing she said was ‘Take care’; and when I got home, a Dear John was in my inbox. Couldn’t call it unexpected. Both of us have been through a messy divorce already, and one’s enough. We’ve agreed we’re still friends. We’ll exchange Christmas cards for a few years, refer to each other without rancor, and probably never meet again.”

Holly nods and makes an “I see” noise in her throat.

A late bus stops outside, its air brakes hissing.

I fail to mention this afternoon’s message to Holly.

My iPhone’s still switched off. Not now. Later.

“LOVELY SHOT, THAT.” There’s a framed photograph on a shelf behind Holly showing her as a young mum, with a small toothy Aoife dressed as the Cowardly Lion with freckles on her nose, and Ed Brubeck, younger than I remember, all smiling in a small back garden in the sun with pink and yellow tulips. “When was it taken?”

“2004. Aoife’s theatrical debut in The Wizard of Oz.” Holly sips her mint tea. “Ed and I mapped out The Radio Peoplearound then. The book was his idea, you know. We’d been in Brighton that weekend, for Sharon’s wedding, and he’d always been Mr. There Has to Be a Logical Explanation.”

“But after the room-number thing, he started believing?”

Holly makes an equivocal face. “He stopped disbelieving.”

“Did Ed ever know what a monster The Radio Peopleturned into?”

Holly shakes her head. “I wrote the Gravesend bits quite quickly, but then I got promoted at the center. What with that, and raising Aoife, and Ed being away, I never got it finished until …” she chooses words with practiced care, “… Ed’s luck ran out in Syria.”

Now I’m appalled by my own self-pity about Zoл and Carmen. “You’re a bit of a hero, our Holly. Heroine, rather.”

“You soldier on. Aoife was ten. Falling to pieces wasn’t an option. My family’d lost Jacko so …” a sad little laugh, “… the Sykes clan does mourning and loss really bloody well. Taking up The Radio Peopleand actually finishing it was therapy, sort of. I never imagined for a minute that anyone outside our family’d want to read it. Interviewers never believe me when I say that, but it’s the truth. The TV Book Club, the Prudence Hanson endorsement, the whole ‘The Psychic with the Childhood Scar’ thing, I wasn’t prepared for any of it, or the websites, the loonies, the begging letters, the people you lost touch with years ago for very good reasons. My first boyfriend—who really did notleave me with fond memories—got in touch to say he’s now Porsche’s main man in West London, and how about a test drive now my ship had come in? Uh, no. Then after the U.S. auction for The Radio Peoplebecame a news item, all the fake Jackos crawled out from under the floorboards. My agent set the first one up via Skype. He was the right age, looked sort oflike Jacko might look, and stared out of the screen, whispering, ‘Oh, my God, oh, my God … It’s you.’ ”

I feel like smoking, but I munch a carrot stick instead. “How did he account for the three missing decades?”

“He said he was kidnapped by Soviet sailors who needed a cabin boy, then taken to Irkutsk to avoid a Cold War incident. Yeah, I know. Brendan’s bullshit detector was buzzing, so he shuftied me over and asked, ‘Recognize me, Jacko?’ The guy hesitated, then burst out, ‘Daddy!’ End of call. The last ‘Jacko’ we interviewed was Bangladeshi, but the imperialists at the British embassy in Dhaka refused to believe he was my brother. Would I send ten thousand pounds and sponsor his visa application? We called it a day after that. IfJacko’s alive, ifhe reads the book, ifhe wants to locate us, he’ll find a way.”

“Were you still working at the homeless center all this time?”

“I quit before I went to Cartagena. A shame—I loved the job, and I think I was good at it—but if you’re chairing a fund-raising meeting the same day a six-figure royalty payment slips into your bank account, you can’t pretend nothing’s changed. More ‘Jackos’ were trying their luck at the office, and my phone was hacked. I’m still involved with homeless charities at a patron level, but I had to get Aoife out of London to a nice sleepy backwater like Rye. So I thought. Did I ever tell you about the Great Illuminati Brawl?”

“You tell me less about your life than you think. The Illuminati: as in the lizard aliens who enslave humanity via beta-blocking mind waves beamed from their secret moonbase?”