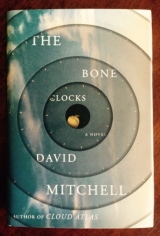

Текст книги "The Bone Clocks"

Автор книги: David Mitchell

Жанры:

Классическое фэнтези

,сообщить о нарушении

Текущая страница: 38 (всего у книги 40 страниц)

I remember how the Horologists could redact bad memories, and wish I could grant Rafiq the same mercy. Or not, I dunno.

“… and most times it’s like it was, with Hamza throwing a ring into the water, telling me, ‘We’ll swim together,’ and he throws me into the water first, but then he never follows. And that’s all I have.” Rafiq dabs his eyes on the back of his hand. “I’ve forgotten everything else. My own family. Their faces.”

“Owain and Yvette Richie of Lifford, up in County Donegal,” says the radio guy, “announce the birth of their daughter Keziah—a dainty but perfect six pounds … Welcome aboard, Keziah.”

“You were five or six, Raf. When you washed up on the rocks below you were in shock, you had hypothermia, you’d seen slaughter at close quarters, you’d drifted for heaven only knows how long in the cold Atlantic, you were alone. You’re not a forgetter, you’re a survivor. I think it’s a miracle you remember anything at all.”

Rafiq takes a clipping of his own hair, fallen onto his thigh, and rubs it moodily between his finger and thumb. I think back to that spring night. It was calm and warm for April, which probably saved Rafiq’s life. Aoife and Цrvar had only died the autumn before, and Lorelei was a mess. So was I, but I had to pretend not to be, for Lorelei’s sake. I was speaking with my friend Gwyn on my tab in my chair when this face appeared at the door, staring in like a drowned ghost. I didn’t have Zimbra yet, so no dog scared him off. Once I’d recovered, I opened the door and got him inside. Where he puked up a liter of seawater. The boy was soaked and shivering and didn’t understand English, or seemed not to. We still had fuel for our boiler at that time, just about, but I understood enough about hypothermia to know a hot bath can trigger arrhythmia and possibly a cardiac arrest, so I got him out of his wet clothes and sat him by the fire wrapped in blankets. He was still shivering, which was another hopeful sign.

Lorelei had woken up by this point, and was making a cup of warm ginger drink for the boy from the sea. I threaded Dr. Kumar but she was busy at Bantry helping with an outbreak of Ratflu, so we were on our own for a couple more days. Our young visitor was feverish, malnourished, and suffered from terrible dreams, but after about a week we, with Mo’s and Branna O’Daly’s help, had nursed him back to relative health. We’d worked out his name was Rafiq by that stage, but where had he come from? Maps didn’t work so Mo Netsourced “Hello” in all the dialects a dark-skinned Asylumite might speak: Moroccan Arabic rang the bell. With Mo’s help, Lorelei studied the language from Net tutorials and became Rafiq’s first English teacher, pulling herself out of mourning for the first time. When an unsmiling Stability officer arrived with Martin, our mayor, to inspect the illegal immigrant about a month later, Rafiq was capable of stringing together basic English sentences.

“The law says he has to be deported,” stated the Stability officer.

Feeling sick, I asked where he’d be deported to, and how.

“Not your problem, Miss Sykes,” stated the Stability officer.

So I asked if Rafiq’d be driven outside the Cordon and dumped like an unwanted dog, ’cause that’s the impression I was getting.

“Not your problem, Miss Sykes,” said the Stability officer.

I asked how Rafiq could legally stay on Sheep’s Head.

“Formal adoption by an Irish citizen,” stated the Stability officer.

Thanking my younger self for acquiring Irish citizenship, I heard myself say that I hereby wished to adopt Rafiq.

“It’s another ration box for your village to fill,” stated the Stability officer. “You’ll need permission from your local mayor.”

Martin read my face and said, “Aye, she has it.”

“ Andyou’d need authorization from a Stability officer of levelfive status or above. Like me, for example.” He ran his tongue along between his front teeth and his closed lips. We all looked at Rafiq, who somehow sensed that his future—his life—was hanging in the balance. All I could think of to say to the Stability officer was “Please.”

The Stability officer unzipped a folder he’d had tucked inside his jacket all along. “I have children too,” he stated.

“AND LAST BUT by no measure least,” mumbles the radio, “to Jer and Maggs Tubridy of Ballintober, Roscommon, a boy, Hector Ryan, weighing in at a whopping eight pounds and ten ounces! Top job, Maggs, and congratulations to all three of you.” Rafiq gives me a look to say he’s sorry he went a bit morbid on me, and I give my adopted grandson a look to say there’s nothing to be sorry about, and get back to cutting the wild whorl of hair about his crown. What little evidence we have suggests Rafiq’s parents are dead, and if they’re not, I don’t know how they’ll ever discover their son’s fate—both the African Net and the Moroccan state had pretty much ceased to exist by the time Rafiq arrived at Dooneen Cottage. But now he’s here, Rafiq’s a part of my family. While I’m alive I’ll look after him the best I can.

The RTЙ news theme comes on, and I turn it up a little.

“Good morning, this is Ruth O’Mally with the RTЙ News at ten o’clock, Saturday, the twenty-eighth of October, 2043.” The familiar news fanfare jingle fades. “At a news conference at Leinster House this morning, the Stability Taoiseach Йamon Kingston confirmed that the Pearl Occident Company has unilaterally withdrawn from the Lease Lands Agreement of 2028, which granted the Chinese consortium trading rights with Cork City and West Cork Enterprise Zone, known as the Lease Lands.”

I’ve dropped the scissors, but all I can do is stare at the radio.

“A Stability spokesman in Cork confirms that control of the Ringaskiddy Concession was returned to Irish authorities at oh four hundred hours this morning, when a POC container vessel embarked with a People’s Liberation Navy frigate escort. The Taoiseach told the assembled journalists that the POC’s withdrawal had been kept secret to ensure a smooth handover of authority, and stated that the POC’s decision has been brought about by questions of profitability. Taoiseach Йamon Kingston added that in no way can the POC’s withdrawal be linked to the security situation, which remains stable in all thirty-four counties. Nor is the decision of the Chinese linked to radiation leaks from the Hinkley Point site in north Devon.”

There’s more news, but I’m no longer listening.

Hens cluck, croon, and crongle in their enclosure.

“Holly?” Rafiq’s scared. “What’s ‘unilaterally withdrawn’?”

Consequences spin off, but one thumps me: Rafiq’s insulin.

“DA’S SAYING IT’LL be okay,” Izzy O’Daly tells us, “and that Stability’ll just keep the Cordon intact, where it is now.” Izzy and Lorelei came running back across the fields from Knockroe Farm and found Rafiq, Zimbra, and me up in Mo’s tidy kitchen. Mo’d heard the same RTЙ report as us, and we’ve been telling Rafiq that not much’ll change, only Chinese imported goods’ll be a little trickier to get hold of than before. The ration boxes will still be delivered by Stability every week, and provision will still be made for special medicines. Rafiq’s reassured, or pretends to be. Declan O’Daly gave Izzy and Lorelei an equally upbeat assessment. “Da says,” Izzy goes on, “that the Cordon was a fifteen-foot razor-wire fence before ten o’clock and it still is after ten o’clock, and there’s no reason for the Stability troops to abandon their posts.”

“Your dad’s a very wise man,” I tell Izzy.

Izzy nods. “Da ’n’ Max’ve gone into town to check on my aunt.”

“Fair play to Declan now,” says Mo. “Kids, if you’d give Zimbra a run in the garden, I’ll make pancakes. Maybe I’ve a dusting of cocoa powder left somewhere. Go on, give Holly and me a little space, hey?”

Once they’re out, a grim and anxious Mo tries to thread friends in Bantry, where the Cordon’s westernmost garrison is stationed. Calls to Bantry normally get threaded without trouble, but today there isn’t even an error message. “I’ve got this nasty feeling,” Mo stares at the blank screen, “that we’ve kept our Net access as long as we have because our threads were routed via the server at Ringaskiddy, and now the Chinese have gone … it’s over.”

I feel as if someone’s died. “No more Net? Ever?”

Mo says, “I might be wrong,” but her face says, No, never.

For most of my life, the world shrank and technology progressed; this was the natural order of things. Few of us clocked on that “the natural order of things” is entirely man-made, and that a world that kept expanding as technology regressed was not only possible but waiting in the wings. Outside, the kids’re playing with a frisbee older than any of them—look closely, you’ll see the phantom outline of the London 2012 Olympics logo. Aoife spent her pocket money on it. It was a hot day on the beach at Broadstairs. Izzy’s showing Rafiq how you step forward and release the frisbee in one fluid motion. I wonder if they’re all putting on a brave face about the end of the Lease Lands, and that really they’re as scared as we are by the threat of gangs, militiamen, land pirates, Jackdaws and God knows what streaming through the Cordon. Zimbra retrieves the frisbee and Rafiq does a better throw, lifted by the wind. Lorelei has to spring up high to catch it, revealing a glimpse of shapely midriff. “Medicine for the chronically ill is one worry,” I speak my thoughts aloud, “but what kind of life will women have, if things carry on the way they are? What if Dуnal Boyce isthe best future the girls in Lol’s class can hope for? Men are always men, I know, but at least during our lives, women have gathered a sort of arsenal of legal rights. But only because, law by law, shifting attitude by shifting attitude, our society became more civilized. Now I’m scared the Endarkenment’ll sweep all that away. I’m scared that Lol’ll just be some bonehead’s slave, stuck in some wintry, hungry, bleak, lawless, Gaelic-flavored Saudi Arabia.”

Lorelei throws the frisbee, but the east wind biffs it off course into Mo’s wall of camellias.

“Pancakes,” says Mo. “I’ll measure the flour and you crack a few eggs. Six should be enough for the five of us?”

· · ·

“WHAT’S THAT SOUND?” asks Izzy O’Daly, half an hour later. Mo’s kitchen table is strewn with the wreckage of lunch. Mo, of course, did unearth a small tub of cocoa powder from one of her bottomless hidden nooks. It must be a year since the last square of waxy Russian chocolate appeared in the ration boxes. Neither me nor Mo had any ourselves, but watching the kids as they ate their chocolate-laced lunch was a sight more delicious than the taste. “There,” says Izzy, “that … crackly noise. Didn’t you hear it?” She looks anxious.

“Raf’s stomach, probably,” says Lorelei.

“Sure I only had one more than you,” objects Rafiq. “And—”

“Yeah, yeah, you’re a growing boy, we know,” says his sister. “Growing into a total pancake monster.”

“There,” says Izzy, making a shushgesture. “Hear it?”

We listen. Like the old woman I am, I say, “I can’t hear—”

Zimbra leaps up, whining, at the door. Rafiq tells him, “Shush, Zimbra!”

The dog shushes, and—there. A spiky, sickening sequence of bangs. I look at Mo and Mo nods back: “Gunfire.”

We rush out onto Mo’s scrubby, dandelion-dotted lawn. The wind’s still from the east and it buffets our ears but now another burst of automatic fire is quite distinct and not far away. Its echo reaches us a couple of seconds later from Mizen Head across the water.

“Isn’t it coming from Kilcrannog?” asks Lorelei.

Izzy’s voice is shaky. “Dad went into the village.”

“The Cordon can’t have fallen al ready,” I blurt, wishing I could stuff the words back in, ’cause by saying it, I feel I’ve helped to make it real. Zimbra is snarling towards the town.

“I’d better get back to the farm,” says Izzy.

Mo and I exchange a look. “Maybe, Izzy,” Mo says, “until we know what we’re dealing with, your parents’d prefer you to lie low.”

Then we hear the noise of jeeps, this side of town, driving along the main lane. More than one or two, by the sound of it.

“Must be Stability,” says Rafiq. “Only they have diesel. Right?”

“Speaking as a mum,” I say to Izzy, “I reallythink you ought—”

“I—I—I’ll stay hidden, I’ll be careful, I promise.” Izzy swallows, and then she’s gone, vanished through a gap in the tall wall of fuchsia.

I hardly have time to dismiss the unpleasant feeling that I’ve just seen Izzy O’Daly for the final time before we notice the timbre of the jeeps has changed, from fast and furious to cautious and growly.

“I think one of the jeeps is coming down our track,” says Lorelei.

Vaguely, I wonder if this blustery autumn day is going to be my last. But not the kids. Not the kids. Mo’s had the same thought: “Lorelei, Rafiq, listen. Just on the off chance this is a militia unit and not Stability, we need you to get Zimbra to safety.”

Rafiq, who still has some cocoa powder in the corner of his lips, is appalled. “But Zim and me are the bodyguards!”

I see Mo’s logic: “If it’s militiamen, they’ll shoot Zim on sight before they even start talking to us. It’s how they work.”

Lorelei’s scared, which she should be. “But what’ll you do, Gran?”

“Mo and I’ll talk to them. We’re tough old birds. But please”—we hear a jeep engine roar in a low gear, sickeningly near—“both of you, go. It’s what your parents would be saying. Go!”

Rafiq’s eyes are still wide, but he nods. We hear brambles scraping against metal sides and small branches being snapped off. Lorelei feels disloyal going, but I mouth “Please”and she nods. “C’mon, Raf, Gran’s counting on us. We can hide him at the sheep bothy above the White Strand. C’mon, Zim. Zimbra. Come on!”

Our spooked, wise dog looks at me, puzzled.

“Go!” I shoo him. “Look after Lol and Raf! Go!”

Reluctantly, Zimbra allows himself to be pulled off and the three are clear of Mo’s garden and over the garden wall behind the polytunnel. We have a wait of about ten seconds before a Stability jeep barges its way through the overgrown track and up onto Mo’s drive, spitting stones. A second jeep appears a few seconds later. The word Stability is stenciled along the side. The forces of law and order. So why do I feel like an injured bird found by a cat?

· · ·

YOUNG MEN CLIMB out, four from each vehicle. Even I can tell they’re not Stability; their uniforms are improvised, they carry mismatched handguns, automatic weapons, crossbows, grenades, and knives, and they move like raiders, not trained soldiers. Mo and I stand side by side, but they walk past us as if we’re invisible. One, perhaps the leader, holds back and watches the bungalow as the others approach it, guns out and ready. He’s scrawny, tattooed, maybe thirty, wears a green beret of military origin, a flak jacket, like Ed used to wear in Iraq, and the winged figure off a Rolls-Royce around his neck. “Anyone else at home, old lady?”

Mo asks him, “What’s the story here, young man?”

“If anyone’s hiding in there, they’ll not be coming out alive. That’s the story here.”

“There’s nobody else here,” I tell him. “Put those guns away before somebody gets hurt, f’Chrissakes.”

He reads me. “Old lady says it’s all clear,” he calls to the others. “If she’s lying, shoot to kill. Any blood’s on her hands now.”

Five militiamen go inside, while two others walk around the outside of the bungalow. Lorelei, Rafiq, and Zimbra should be across the neighboring field by now. The strip of hawthorn should hide them from then on. The leader takes a few steps back and examines Mo’s roof. He jumps onto the patio wall to get a better view.

“Will you pleasetell us,” says Mo, “what you want?”

Inside Mo’s bungalow, a door slams. Below, in their coop, my surviving chickens cluck. Over in O’Daly’s pasture, a cow lows. From the road to the end of Sheep’s Head, more jeeps roar. A militiaman emerges from Mo’s shed, calling out, “Found a ladder in here, Hood. Shall I bring it out?”

“Yep,” says the apparent leader. “It’ll save unloading ours.”

The five men now reemerge from Mo’s bungalow. “All clear inside, Hood,” says a bearded giant. “Blankets and food, but there’s better in the village store.”

I look at Mo: Does this mean they killed people in Kilcrannog?

Militiamen kill. It’s how they carry on being militiamen.

“We’ll just take the panels, then,” says Hood, telling us, “Your lucky day, old ladies. Wyatt, Moog, the honor is yours.”

Panels? Two of the men, one badly scarred by Ratflu, prop the ladder against the end gable of the bungalow. Up they climb, and we see what they want. “No,” says Mo. “You can’t take my solar panels!”

“Easier’n you’d think, old lady,” says the bearded giant, holding the ladder steady. “One pair o’ bolt cutters, lower her down gently, job’s done. We’ve done it a hundred times, like.”

“I need my panels for light,” protests Mo, “and for my tab!”

“Seven days from now,” Hood predicts, “you’ll be praying for darkness. It’ll be your only protection ’gainst the Jackdaws. Look on it as a favor we’re doing you. And you won’t be needing your tabs anymore, neither. No more Net for the Lease Lands. The good old days are good and gone, old lady. Winter’s coming.”

“You call yourself ‘Hood,’ ” Mo tells him, “but it’s ‘Robbing Hood,’ not Robin Hood, from where I’m standing. Would you treat yourelderly relatives like this?”

“Number one is to survive,” answers Hood, watching the men on the roof. “They’re all dead, like my parents. They had a better life than I did, mind. So did you. Your power stations, your cars, your creature comforts. Well, you lived too long. The bill’s due. Today,” up on the roof the bolt is cut on the first panel, “you start to pay. Think of us as the bailiffs.”

“But it wasn’t us, personally, who trashed the world,” says Mo. “It was the system. We couldn’t change it.”

“Then it’s not us, personally, taking your panels,” says Hood. “It’s the system. We can’t change it.”

I hear the O’Dalys’ dog barking, three fields away. I pray Izzy’s okay, and that these men with guns don’t molest the girls. “What’ll you do with the panels?” I ask.

“The mayor of Kenmare,” says Hood, as a couple of his men carry the first of Mo’s panels over to the jeep, “he’s building himself quite a fastness. Big walls. A little Cordon of his own, with surveillance cameras, lights. Pays food and diesel for solar panels.” A bolt affixing Mo’s second solar panel is cut. “These and the ones from the house below”—he nods at my cottage—“are going to him.”

Mo’s quicker than me: “My neighbor has no solar panels.”

“Someone’s telling porkies,” singsongs the bearded giant. “Mr. Drone says they do, and Mr. Drone never lies.”

“That drone yesterday was yours?” I ask, as if it’ll help.

“Stability finds the booty,” says the giant, “we go ’n’ get it. Don’t look so gobboed, old lady. Stability’s just another clan o’ militia, nowadays. Specially now the Chinks’ve gone.”

I imagine my mother saying, It’s “Chinese,” not “Chinks.”

Mo asks, “What gives you the right to take our property?”

“Guns gives us the right,” says Hood. “Plain ’n’ simple.”

“So you’re reinstating the law of the jungle?” asks Mo.

“You were bringing it back, every time you filled your tank.”

Mo stabs the ground with her stick. “A thief, a thug, and a killer!”

He considers this, stroking his eyebrow ring. “Killer: When it’s kill or be killed, yeah, I am. Thug: We all have our moments, old lady. Thief: Actually, I’m a trader, too, like. You give me your solar panels—I’ll give you glad tidings.” He reaches into his pocket and brings out two short white tubes. I’m so relieved it’s not a gun I extend my hand when he holds them out. I stare at the pill canisters, at their skull and crossbones, their Russian writing. Hood’s voice is less mocking now. “They’re a way out. If the Jackdaws come, or Ratflu breaks out, or whatever, and there’s no doctor. Instant antiemetic,” he says, “and enough pentobarbital for a dignified ending in thirty minutes. We call ’em huckleberries. You drift away painless, like. Childproof container, too.”

“Mine’s going into the cesshole,” says Mo.

“Give it back, then,” Hood says. “There’s plenty who’ll want one.” Mo’s second solar panel’s off the roof and is being carried past us to the jeep. I slip both canisters into my pocket: Hood notices and gives me a conspiratorial look I ignore. “Anyone in the house down below,” he nods at the cottage, “the lads need to know about?”

With acute retrospective envy, I remember how Marinus could “suasion” people into doing his bidding. All I have is language. “Mr. Hood. My grandson’s got diabetes. He controls it with an insulin pump that needs recharging every few days. If you take the solar panels, you’ll be killing him. Please.”

Up the hill, sheep bleat, oblivious to human empires rising and falling. “That’s bad luck, old lady, but your grandson’s born into the Age of Bad Luck. He was killed by a bossman in Shanghai who figured, ‘The West Cork Lease Lands ain’t paying their way.’ Even if we left your panels on your roof, they’d be Jackdawed off in seven days.”

Civilization’s like the economy, or Tinkerbell: If people stop believing it’s real, it dies. Mo asks, “How do you sleep at night?”

“Number one is to survive,” Hood repeats.

“That’s no answer,” snorts my neighbor. “That’s a huckleberry you force-feed to what’s left of your conscience.”

Hood ignores Mo and, with a gentleness I’d not have guessed at, he cups my hand under his larger one and presses a third canister into the hollow of my palm. Hope seeps through holes in the soles of my feet. “There’s no one in the house below. Don’t hurt my hens. Please.”

“We’ll not touch a feather, old lady,” promises Hood.

The bearded giant’s already carrying the ladder down the track to Dooneen Cottage when an explosion punches a hole through the tight quiet of the afternoon. Everyone crouches, tense—even Mo and me.

From Kilcrannog? There’s an echo, and an echo’s echo.

Someone calls out, “What the holy feckwas that?”

The Ratflu-scarred kid points and says, “Over there …”

Rising into view above the fuchsia thicket we see a fat genie of orange-tinged oil-black smoke fly upwards, before the wind sucks it away over Caher Mountain. A raspy voice says, “The feckin’ oil depot!”

Hood slaps his earset and flips up a mike piece. “Mothership, this is Rolls-Royce, our location’s Dooneen, one mile west of Kilcrannog. What’s with that big bang? Over.”

Across the fields we hear the sickening percussion of gunfire.

“Mothership, this is Rolls-Royce—d’you need help? Over.”

Through Hood’s helmet we hear a smear of frantic speech, panicky static, and nothing more.

“Mothership? This is Rolls-Royce. Respond, please. Over.” Hood waits, staring at the smoke still streaming up from the town. He slaps his headset again: “Audi? This is Rolls-Royce. Are you in contact with Mothership? And what’s happening in town? Over.” He waits. We all do, watching him. More silence. “Lads, either the peasants are revolting or we’ve got company from across the Cordon sooner than we thought. Either way, we’re needed back at the town. Fall back.”

The eight militiamen return to the jeeps without a glance at Mo or me. The jeeps reverse down Mo’s short drive, and thump their way back up the track towards the main road.

Towards Kilcrannog, the gunfire grows more intense.

We can still recharge Rafiq’s insulin pump, I realize.

For now, at least: Hood said the Jackdaws are coming.

“Didn’t even put my bloody ladder back,” mutters Mo.

FIRST I GO and get the kids from White Strand. The waves in Dunmanus Bay never look sure which way to run when the wind’s from the east. Zimbra runs out of the old corrugated-iron shelter, followed by a nervy, relieved Lorelei and Rafiq. I tell them about the militiamen and the solar panels, and we walk back to Dooneen Cottage. Gunshots still dot-and-dash the afternoon, and as we turn back we see a drone circle over the village at one point. After a sustained burst of gunfire, Rafiq’s keen eyes see it shot down. A jeep roars along the road up above. We find a giant puffball at the edge of the meadow, and although food’s the last thing on my mind we pick it and Lorelei carries it home like a football. Fried in butter, its sliced white flesh will make the bones of a meal for the four of us—Christ knows when, or if, we’ll be seeing a ration box again. Probably I have about five weeks’ food in my parlor and the polytunnel, if we’re careful. Assuming no gang of armed men steals it.

Back at the cottage I find Mo feeding the hens. She tried to patch friends in the village, in Ahakista, Durrus, and Bantry, but the Net’s well and truly dead. As is the radio, even the RTЙ station. “All across the bandwidths,” she says, “it’s the silence of the tomb.”

What now? I have no idea what to do: Barricade us in, send the kids to some remoter spot, like the lighthouse, go to the O’Dalys at Knockroe Farm to see what happened to Izzy and her family, or what? We’ve got no weapons, though given the number of rounds being fired on the Sheep’s Head this afternoon, a gun’s likelier to get you killed than save your life. All I know is that unless danger is careering down the Dooneen track in a jeep, I’m less fretful if Lorelei and Rafiq are right by me. Of course, if we’re all absorbing high levels of radioactive isotopes it’s all pretty academic, but let’s take it one apocalypse at a time.

The commodity we’re most in need of is news. The gunfire’s stopped in the village, but until we know the lie of the land, we should steer clear. The O’Dalys’ll probably know more, if Declan’s got back okay. Their farm feels a long way off on such a violent afternoon, but Lorelei and I set out. I ask Rafiq to stay at the cottage with Zimbra to guard Mo, but tell him that, whatever happens, his first duty is to stay alive. That’s what his family in Morocco would want; that’s why they tried to get him to Norway. Which maybe wasn’t the best thing to say, but if there was a book called The Right Things to Do and Say as Civilization Dies, I’ve never read it.

WE FOLLOW THE shore to Knockroe Farm, past the rocks where I harvest carrageen sea moss and kelp, and across the O’Dalys’ lower grazing pasture. Their small herd of Jerseys approaches us, wanting to be milked; not a good sign. The farmyard’s ominously quiet too, and Lorelei points out that the solar panels on the old stables are gone. Izzy said earlier that Declan and the eldest son, Max, went into the village this morning, but Tom or Izzy or their mum, Branna, should be around. No sign of the farm sheepdog, Schull, either, or English Phil the shepherd. The kitchen door’s banging in the wind and I find Lorelei’s hand in mine. The door was kicked in. We pass the manure pile, cross the yard, and my voice is trembling as I call into the kitchen, “Hello? Anyone home?”

No reply. The wind trundles a can along.

Branna’s wind chime’s chiming by the half-open window.

Lorelei shouts as loud as she dares: “IZZY! IT’S US!”

I’m afraid to go farther into the house.

The breakfast plates are still in the sink.

“Gran?” Lorelei’s as scared as me. “Do you think …”

“I don’t know, love,” I tell her. “You wait outside, I’ll—”

“Lol? Lol!” It’s Izzy, with Branna and Tom following, crossing the yard behind us. Tom and Izzy look unhurt but shaken, but Branna O’Daly, a black-haired no-nonsense woman of fifty, has blood all over her overalls. I almost shriek, “Branna! Are you hurt?” Branna’s as puzzled as I am horrified, then realizes: “Oh, Mother of Jesus, Holly, no no no, it’s not a gunshot wound, it’s one of our cows, calving. The Connollys’ bull got into the paddock last spring, and she went into labor earlier. Timing, eh? She didn’t know that the Cordon’d fallen and gangs of outlaws were roaming the countryside taking solar panels at gunpoint. A messy breech birth, too. Still, she gave birth to a female, so one more milker.”

“They took your panels, Branna,” says Lorelei.

“I know, pet. Nothing I could do to stop them. Did they pay a courtesy call down Dooneen track, I wonder?”

“They stole Mo’s panels off her roof too,” I say, “but when they heard the explosion they left, before they took mine.”

“Yes, our crew cleared off at the same time.”

I ask Branna, “What about Declan and Max?” and she shrugs and shakes her head.

“They’re not back from the village,” says Tom, adding disgustedly, “Mam won’t let me go and find them.”

“Two out of three O’Daly males in a war zone is enough.” Branna’s worried sick. “Da told you to defend the home front.”

“You made me hide,” Tom’s sixteen-year-old voice cracks, “in the fecking hay loft with Izzy! That’s not defending.”

“I made you hide in the what?” says Branna, icily.

Tom scowls, just as icily. “In the loft with Izzy. But why—”

“Eight bandits with the latest Chinese automatics,” Izzy tells him, “versus one teenager with a thirty-year-old rifle. Guess the score, Tom. Anyway: I believe I hear a bicycle. Speak of the devil?”

Tom has only just time to say, “What?” before Schull starts barking at the farm gate, wagging his tail, and round the corner—on a mountain bike—comes Tom’s brother Max.

He skids to a halt a few yards away. He’s got a nasty gash across one cheekbone and wild eyes. Something terrible’s happened.

“Max!” Branna looks appalled. “Where’s Da? What’s happened?”

“Dad’s—Dad’s,” Max’s voice wobbles, “alive. Are you all all right?”

“Yes, thanks be to God—but your eye, boy!”

“It’s fine, Ma, just a bit of stone from a … The fuel depot got blown to feckereens and—”

His mum’s hugging Max too tight for him to speak. “What’s with all the cussing in this house?” says Branna, over his shoulder. “Your father and I didn’t raise you to speak like a gang o’ feckin’ gurriers, did we? Now tell us what happened.”

WHILE I CLEAN Max’s gashed cheek in the O’Dalys’ kitchen, he drinks a glass of his father’s muddy home brew to steady himself and a mug of mint tea to muffle the taste of the home brew. He finds it hard to begin until he begins. Then he hardly pauses for breath. “Da and me’d just got to Auntie Suke’s when Mary de Bъrka’s eldest, Sam, calls round, saying there’s an emergency village meeting at the Big Hall. That was noon, I think. Pretty much the whole village was there. Martin stood up first, saying he’d called the meeting because of the Cordon falling and that. He said we should put together Sheep’s Head Irregular Regiment—armed with whatever shotguns we had at home—to man roadblocks on the Durrus road and the Raferigeen road, so if or when Jackdaws break through the Cordon, we’d not just be sat around like turkeys waiting for Christmas, like. Most of the boys thought it was a sound enough idea, like. Father Brady spoke next, saying that God would let the Cordon fall because we’d put our faith in false idols, a barbedwire fence, and the Chinese, and the first thing to do was choose a new mayor who’d have God’s support. Pat Joe and a few o’ the lads were like, ‘F’feck’s sake, this is no time for electioneering!’ so Muriel Boyce was shrieking at them that they’d burn, burn, burn because whoever thought a pack o’ sheep farmers with rusty rifles could stop the Book of Revelation coming true was a damned eejit who’d soon be a dead damned eejit. Then Mary de Bъrka nnhgggffftchtchtch …” Max grimaces as I extract a small flake of stone from his cut with a pair of tweezers.