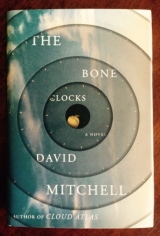

Текст книги "The Bone Clocks"

Автор книги: David Mitchell

Жанры:

Классическое фэнтези

,сообщить о нарушении

Текущая страница: 36 (всего у книги 40 страниц)

Five years later, I take a deep, shuddery breath to stop myself crying. It’s not just that I can’t hold Aoife again, it’s everything: It’s grief for the regions we deadlanded, the ice caps we melted, the Gulf Stream we redirected, the rivers we drained, the coasts we flooded, the lakes we choked with crap, the seas we killed, the species we drove to extinction, the pollinators we wiped out, the oil we squandered, the drugs we rendered impotent, the comforting liars we voted into office—all so we didn’t have to change our cozy lifestyles. People talk about the Endarkenment like our ancestors talked about the Black Death, as if it’s an act of God. But we summoned it, with every tank of oil we burned our way through. My generation were diners stuffing ourselves senseless at the Restaurant of the Earth’s Riches knowing—while denying—that we’d be doing a runner and leaving our grandchildren a tab that can never be paid.

“I’m so sorry, Lol.” I sigh, looking around for a box of tissues before remembering our world no longer has tissues.

“It’s all right, Gran. It’s good to remember Mum and Dad.”

Upstairs, Rafiq is hopping along the landing—probably pulling on a sock—as he sings in hybrid Mandlish. Chinese bands are as cool to kids in the Cordon as American New Wave bands were to me.

“We’re luckier, in a way,” Lorelei says quietly. “Mum and Dad didn’t … Y’know, it was all over so quickly, and they had each other, and at least we know what happened. But for Raf …”

I look at Aoife and Цrvar. “They’d be so proud of you, Lol.”

Then Rafiq appears at the top of the stairs. “Is there any honey for the porridge, Lol? Morning, Holly, by the way.”

SCHOOL BAGS PACKED, lunches stowed, Lorelei’s hair braided, Rafiq’s insulin pump checked and his blue tie—the last vestige of a uniform the school at Kilcrannog can reasonably insist on—done again and redone, we set off up the track. Caher Mountain, whose southern face I’ve looked at in all seasons, all weathers, and all moods nearly every day over the last twenty-five years, rises ahead. Cloud shadows slide over its heathered, rocky, gorse-patched higher slopes. Lower down is a five-acre plantation of Monterey pines. I push the big pram that was already a museum piece when me and Sharon used to play with it during summer holidays here in the late seventies.

Mo’s up and out. She’s hanging clothes on her line as we get to her gateway, wearing a fisherman’s geansa нso stretched it’s almost a robe. “Morning, neighbors. Friday again. Who knows where the weeks go?” The white-haired ex-physicist grabs her stick and hobbles across the rough-cropped lawn, handing me her empty ration box to take to town. “Thanks in advance,” she says, and I tell her, “No bother,” and add it to Lorelei’s, Rafiq’s, and mine in the pram.

“Let me help with that washing, Mo,” says Lorelei.

“The washing I can handle, Lol, but yomping off to town,” as we call the village of Kilcrannog, “I can’t. What I’d do without your gran to fill up my ration box, I cannot imagine.” Mo whirls her cane like a rueful Chaplin. “Well, actually I can: starve by degrees.”

“Nonsense,” I tell her. “The O’Dalys’d take care of you.”

“A fox killed four of our chickens last night,” says Rafiq.

“That’s regrettable.” Mo glances at me, and I shrug. Zimbra sniffs a trail all the way up to Mo, wagging his tail.

“We’re lucky Zimmy got him before he killed the lot,” says Rafiq.

“My, my.” Mo scratches behind Zimbra’s ear and finds the magic spot that makes him go limp. “Quite a night at the opera.”

I ask, “Did you have any luck on the Net last night?” Meaning, Any news about the Hinkley Point reactor?

“Only a few minutes, on official threads. Usual statements.” We leave it there, in front of the kids. “But drop by later.”

“I was half hoping you’d mind Zimbra for us, Mo,” I say. “I don’t want him going all Call of the Wildon us after killing the fox.”

“Course I will. And, Lorelei, would you tell Mr. Murnane I’ll be in the village on Monday to teach the science class? Cahill O’Sullivan’s taking his horse and trap in that day and he’s offered me a lift. I’ll be borne aloft like the Queen of Sheba. Off you go now, I mustn’t make you late. C’mon, Zimbra, see if we can’t find that revolting sheep’s shin you buried last time …”

AUTUMN’S AT ITS tipping point. Ripe and gold is turning manky and cold, and the first frost isn’t far off. In the early 2030s the seasons went badly haywire, with summer frosts and droughts in winter, but for the last five years we’ve had long, thirsty summers, long, squally winters, with springs and autumns hurrying by in between. Outside the Cordon the tractor’s going steadily extinct and harvests have been derisory, and on RTЙ two nights ago there was a report on farms in County Meath that are going back to using horse-drawn plows. Rafiq trots ahead, picking a few late blackberries, and I encourage Lorelei to do the same. Vitamin supplements in the ration boxes have grown fewer and further between. Brambles grow as vigorously as ever, at least, but if we don’t shear them back soon, our track up to the main road’ll turn into the hedge of thorns round Sleeping Beauty’s castle. Must speak to Declan or Cahill about it. The puddles are getting deeper and the boggy bits boggier, too, and here and there Lorelei has to help me with the pram; more’s the pity I didn’t have the whole track resurfaced when money still got things done. More’s the pity I didn’t lay in better, deeper, bigger stores, too, but we never knew that every temporary shortage would turn out to be a permanent one until it was too late.

We pass the spring that feeds my cottage’s and Mo’s bungalow’s water tanks. It’s gurgling away nicely now after the recent rains, but last summer it dried up for a whole week. I never pass the spring without remembering Great-aunt Eilнsh telling me about Hairy Mary the Contrary Fairy, who lived there, when I was little. Being so hairy the other fairies laughed at her, which made her so cranky she’d reverse people’s wishes out of spite, so you had to outwit her by asking for what you didn’twant. “I neverwant a skateboard” would get you a skateboard, for example. That worked for a bit till Hairy Mary cottoned on to what people were doing, so half the time she gave people what they wished for, and half the time she gave them the opposite. “So the moral is, my girl,” Great-aunt Йilish says to me across the six decades, “if you want a thing, get it the old-fashioned way, by elbow grease and brain power. Don’t mess with the fairies.”

But today, I don’t know why, maybe it’s the fox, maybe it’s Hinkley, I take my chances. Hairy Mary, Contrary Fairy: Please, let my darlings survive. “Please.”

Lorelei turns and asks, “You okay, Gran?”

WHERE DOONEEN TRACK reaches the main road we turn right and soon pass the turnoff leading down to Knockroe Farm. We meet the farm’s owner, Declan O’Daly, hauling a handcart of hay. Declan’s around fifty, is married to Branna, has two older boys plus a daughter in Lorelei’s class, owns two dozen Jerseys and about two hundred sheep, which graze on the rockier, tuftier end of the peninsula. His Roman brow, curly beard, and lived-in face give him the air of a Zeus gone to seed a bit, but he’s helped Mo and us out more than a few times and I’m glad he’s there. “I’d give you a big hug,” he says, walking across the farmyard to the road in stained overalls, “but one of the cows just knocked me over into a huge pile of cow shite. What’s so funny,” he mock-fumes, “young Rafiq Bayati? By God, I’ll use you as a rag …”

Rafiq’s shaking with silent giggling and hides behind me as Declan lumbers over like a manure-spattered Frankenstein.

“Lol,” Declan says, “Izzy told me to say sorry but she’s gone on into the village early to help her aunt get her veg boxed up for the Convoy. You’re coming for a sleepover later, I am informed?”

“Yes, if that’s still okay,” says my granddaughter.

“Ach, you’re hardly a rugby squad now, are ye?”

“It’s still good of you to feed an extra mouth,” I say.

“Guests who help with the milking are more than—” Declan stops and looks up at the sky.

“What’s that?” Rafiq squints up towards Killeen Peak.

I can’t see it at first but I hear a metallic buzzing, and Declan says, “Would you look at that now …”

Lorelei asks, disbelievingly, “A plane?”

There. A sort of gangly powered glider. At first I think it’s big and far, but then I see it’s small and near. It’s following Seefin and Peakeen Ridges, aiming towards the Atlantic.

“A drone,” says Declan, his voice strained.

“Magno,”says Rafiq, enraptured: “A real live UAV.”

“I’m seventy-four,” I remind him, sounding grumpy.

“Unmanned aerial vehicle,” the boy answers. “Like a big remotecontrol plane, with cameras attached. Sometimes they have missiles, but that one’s too dinky, like. Stability has a few.”

I ask, “What’s it doing here?”

“If I’m not wrong,” says Declan, “it’s spying.”

Lorelei asks, “Why’d anyone bother spying on us?”

Declan sounds worried: “Aye, that’s the question.”

“ ‘I AM the daughter of Earth and Water,’ ” recites Lorelei, as we pass the old rusting electrical substation,

“And the nursling of the Sky;

I pass through the pores of the oceans and shores;

I change, but I cannot die.”

I wonder about Mr. Murnane’s choice of “The Cloud.” Lorelei and Rafiq aren’t unique: Many kids at Kilcrannog have had at least one parent die as the Endarkenment has set in. “Oh, I can’t be lieveI’ve forgotten this bit again, Gran.”

“For after the rain …”

“Got it, got it.

“For after the rain when with never a stain,

The pavilion of Heaven is bare,

And the winds and sunbeams with their convex gleams—”

“Um …

“Build up the blue dome of air …”

Unthinkingly, I’ve looked up at the sky. My imagination can still project a tiny glinting plane onto the blue. Not an overgrown toy like the drone—though that was remarkable enough—but a jet airliner, its vapor trail going from sharp white line to straggly cotton wool. When did I last see one? Two years ago, I’d say. I remember Rafiq running in with this wild look on his face and I thought something was wrong, but he dragged me outside, pointing up: “Look, look!”

Up ahead, a rat runs into the road, stops, and watches us.

“What’s a ‘convex’?” asks Rafiq, picking up a stone.

“Bulging out,” says Lorelei. “ ‘Concave’ is bulging in, like a cave.”

“So has Declan got a convex tummy?”

“Not as convex as it was, but let Lol get back to Mr. Shelley.”

“ ‘Mr.’?” Rafiq looks dubious. “Shelley’s a girl’s name.”

“That’s his surname,” says Lorelei. “He’s Percy Bysshe Shelley.”

“Percy? Bysshe? His mum and dad must’ve hatedhim. Bet he got crucified at school.” He throws his stone at the rat. It just misses and the rat runs into the hedgerow. Once I would’ve told Rafiq not to use living things for target practice but since the Ratflu scare, different rules have applied. “Go on, Lol,” I say. “The poem.”

“I think I’ve got the rest.

“I silently laugh at my own cenotaph,

And out of the caverns of rain,

Like a child from the womb, like a ghost from the tomb,

I arise and unbuild it again.”

“Perfect. Your dad had an amazing memory, too.”

Rafiq plucks a fuchsia flower and sucks its droplet of nectar. Sometimes I think I shouldn’t refer to Цrvar in front of Rafiq, ’cause I never met his father. Rafiq doesn’t sound upset, though: “The womb’s where the baby is inside the mum, right, Holly?”

“Yes,” I tell the boy.

“And what’s a senno-thingy?”

“A cenotaph. A monument to a person who died, often in a war.”

“I didn’t get the poem either,” says Lorelei, “till Mo explained it. It’s about birth and rebirth andthe water cycle. When it rains, the cloud’s used up, so it’s sort of died; and the winds and sunbeams build the dome of blue sky, which is the cloud’s cenotaph, right? But then the rain that wasthe old cloud runs to the sea where it evaporates and turns into a new cloud, which laughs at the blue dome—its own gravestone—’cause now it’s resurrected. Then it ‘unbuilds’ its gravestone by rising up into it. See?”

A gorse thicket scents the air vanilla and glints with birdsong.

“I’m glad we’re doing ‘Puff the Magic Dragon,’ ” says Rafiq.

AT THE SCHOOL gate Rafiq tells me, “Bye!” and scuttles off to join a bunch of boys pretending to be drones. I’m about to call out, “Mind your insulin pump!” but he knows we’ve only one more in store, and why embarass him in front of his friends?

Lorelei says, “See you later, then, Gran, take care at the market,” as if she’s the adult and I’m the breakable one, and goes over to join a cluster of half-girls, half-women by the school entrance.

Tom Murnane, the deputy principal, notices me and strides over. “Holly, I was after a word with you. Would you still be wanting Lorelei and Rafiq to sit out of the religion class? Father Brady, the new priest, is starting Bible study classes over in the church from this morning.”

“Not for my two, Tom, if it’s no bother.”

“That’s grand. There’s eight or nine in the same boat, so they’ll be doing a project on the solar system instead.”

“And will the earth be going round the sun or vice versa?”

Tom gets the joke. “No comment. How’s Mo feeling today?”

“Better, thank you, and I’m glad you mentioned it, my mem—” I stop myself saying, “My memory’s like a sieve,” because it’s not funny anymore. “Cahill O’Sullivan’s bringing her in on his horsetrap next Monday, so she can teach the science class, if it still suits.”

“If she’s up to it she’s welcome, but be sure and tell her not to bust a gut if her ankle needs more time to recuperate.” The school bell goes. “Must dash now.” He’s gone.

I turn around and find Martin Walsh, the mayor of Kilcrannog, waving goodbye to his daughter, Roisнn. Martin’s a large pink man with close-cropped white hair, like Father Christmas gone into nightclub security. He always used to be clean-shaven, but disposable razors stopped appearing in the ration boxes eighteen months ago and now most men on the peninsula are sporting beards of one sort or another. “Holly, how are ye this morning?”

“Can’t complain, Martin, but Hinkley Point’s a worry.”

“Ach, stop—have ye heard from your brother in the week?”

“I keep trying to thread a call, but either I get a no-Net message, or the thread frays after a few seconds. So, no: I haven’t spoken with Brendan since a week ago, when the hazard alert went up to Low Red. He’s living in a gated enclave outside Bristol, but it’s not far from the latest exclusion zone and hired security’s no use against radiation. Still,” I resort to a mantra of the age, “what can’t be helped can’t be helped.” Pretty much everyone I know has a relative in danger, or at least semi-incommunicado, and fretting aloud has become bad etiquette. “Roisнn was looking right as rain just now, I saw. It wasn’t mumps, after all?”

“No, no, just swollen glands, thanks be to God. Dr. Kumar even had some medicine. How’s our local cyberneurologist’s ankle?”

“On the mend. I caught her hanging out washing earlier.”

“Excellent. Be sure to tell her I was asking after her.”

“I will—and actually, Martin, I was hoping for a word.”

“Of course.” Martin leans in close, holding my elbow as if he, not I, is the slightly deaf one—as public officials do to frail old dears the week before election in a community of a mere three hundred voters.

“Do you know if Stability’ll be distributing any coal before the winter sets in?”

Martin’s face says, Wish I knew. “If it gets here, the answer’s yes. Same old problem: There’s a tendency for our lords and masters in Dublin to look at the Cordon Zone, think, Well, that bunch are living off the fat of the land, and wash their hands of us. My cousin at Ringaskiddy was telling me the collier docked last week with a cargo of coal from Poland, but when there’ll be fuel enough to fill the trucks to distribute it is another matter.”

“And a shower o’ feckin’ thievers ’tween Ringaskiddy and Sheep’s Head there are so,” says Fern O’Brien, appearing from nowhere, “and coal falls off lorries at a fierce old rate. I’ll not be holding my breath.”

“We raised the subject,” says Martin, “at the last committee meeting. A few o’ the lads and me’re planning a little excursion up Caher Saddle for a spot o’ turf cutting. Ozzy at the forge has made a—what’s the word?—a compressor for molding turf logs, so big.” Martin’s hands are a foot apart. “Now sure it’s not coal, but it’s a sight better than nothing, and if we don’t leave Five Acre Wood alone, it’ll be No Acre Wood in no time, like. Once we’ve the logs dried, I’ll have Fнonn drop down a load each to you and Mo on his next diesel run to Knockroe Farm—whoever you cast your ballot for. Frost doesn’t care about politics, and we need to look after our own.”

“I’m voting for the incumbent,” I assure him.

“Thank you, Holly. Every last vote will count.”

“There’s no serious opposition, is there?”

Fern O’Brien points behind me to the church noticeboard. Over I go to read the new, large hand-drawn poster:

ENDARKENMENT IS GOD’S JUDGMENT

GOD’S FAITHFULL SAY “ENOUGH!”

VOTE FOR THE LORD’S PARTY

MURIEL BOYCE FOR MAYOR

“Muriel Boyce? Mayor?But Muriel Boyce is, I mean …”

“Muriel Boyce is not to be underestimated,” says Aileen Jones, the ex–documentary maker turned lobster fisherwoman, “and thick as thieves with our parish priest, even if they can’t spell ‘faithful.’ There’s a link between bigotry and bad spelling. I’ve met it before.”

I ask, “Father McGahern never did politics in church, did he?”

“Never,” Martin replies. “But Father Brady’s cut from a different cloth. Come Sunday I’ll be sat there in our pew while our priest tells us that God’ll only protect your family if you vote for the Lord’s Party.”

“People aren’t stupid,” I say. “They won’t swallow that.”

Martin looks at me as if I don’t see the whole picture. I get this look a lot these days. “People want a lifeboat and miracles. The Lord’s Party’s offering both. I’m offering peat logs.”

“But the lifeboat isn’t real, and the peat logs are. Don’t give up. You’ve a reputation for sound decisions. People listen to reason.”

“Reason?” Aileen Jones is grimly cheerful. “Like my old doctor friend Greg used to say, if you could reason with religious people, there wouldn’t be any religious people. No offense, Martin.”

“I’m beyond offense at this point, Fern,” says our mayor.

UP CHURCH LANE we come to Kilcrannog square. Ahead is Fitzgerald’s bar, a low, rambling building as old as the village. It’s been added to over the centuries and painted white, though not recently. Crows roost on its ridge tiles and gables as if up to no good. On our right’s the diesel depot, which was a Maxol garage when I first moved here, and where we used to fill up our Toyotas, our Kias, our VWs like there was no tomorrow. Now it’s just for the Co-op tanker that goes around from farm to farm. On the left’s the Co-op store, where the ration boxes’ll be distributed later by the committee, and on the south side of the square’s the Big Hall. The Big Hall also serves as a marketplace on Convoy Day, and we go in, Martin holding the door open so I can wheel in my pram. The hall’s noisy but there’s not a lot of laughter today—Hinkley Point casts a long shadow. Martin says he’ll see me later and goes off electioneering, Aileen looks for Ozzy to speak about metal parts for her sailboat, and I start foraging through the stalls. I browse among the trestle tables of apples and pears and vegetables too misshapen for Pearl Corp, home-cured bacon, honey, eggs, marijuana, cheese, homebrewed beer and poitнn, plastic bottles and containers, knitted clothes, old clothes, tatty books, and a thousand things we used to give to charity shops or send to the landfill. When I first moved to the Sheep’s Head Peninsula thirty years ago, a West Cork market was where local women sold cakes and jam for the craic, West Cork hippies tried to sell sculptures of the Green Man to Dutch tourists, and people on middle-class incomes bought organic pesto, Medjool dates, and buffalo mozzarella. Now the market’s what the supermarket used to be: where you get everything, bar the basics found in the ration boxes. With our modified prams, pushchairs, and old supermarket trolleys, we’re a hungry-looking, unshaven, cosmeticless, jumble-sale parody of a Lidl or Tesco or Greenland only five or six years ago. We barter, buy, and sell with a combination of guile, yuan, and Sheep’s Head dollars—numbered metal disks engraved by the three mayors of Durrus, Ahakista, and Kilcrannog. I turn forty-eight eggs into cheap Chinese shampoo you can also use to wash clothes; some bags of seaweed salt and bundles of kale into undyed wool from Killarney to finish a blanket; redcurrant jelly—the jars are worth more than the jelly—into pencils and a pad of A4 paper to stitch some more exercise books, as the kids’ copy books have been rubbed out so often that the pages are almost see-through; and, reluctantly, a last pair of good Wellington boots I’ve had in their box for fifteen years into sheets of clear plastic, which I’ll use to make rain capes for the three of us, and to fix the polytunnel after the winter gales. Plastic sheeting’s hard to find, and Kip Sheehy makes a predictable face, but waterproof boots are even rarer, so by saying, “Maybe another time, then,” and walking off I get him to throw in a twenty-meter length of acrylic cord and a bundle of toothbrushes as well. I worry about Rafiq’s teeth. There’s very little sugar in our—or anyone’s—diet, but there are no dentists west of Cork anymore.

I chat with Niamh Murnane, Tom Murnane’s wife, who’s sitting at a table with hemp sacks of oats and sultanas; Stability no longer has any yuan to pay teachers, so it’s sending out salaries of tradeable foodstuffs instead. I was hoping to find sanitary towels for Lorelei, too, as Stability no longer includes them on the list of necessities, but I’m told there weren’t any on the last Company container ship. Branna O’Daly uses strips of old bedsheets, which we’ll need to wash, ’cause even old bedsheets are getting rarer. If only I’d had the foresight to lay in a store of tampons a few years back. Still. Complaining is rude to the three-million-odd souls who have to somehow survive outside the Cordon.

· · ·

IN THE ANNEX, Sinйad from Fitzgerald’s bar serves hot drinks and soup made on the kitchen range that keeps the Big Hall warm in winter. As I trundle up with my pram, Pat Joe, the Co-op mechanic, pulls up a chair for me with his giant oily hands, and by now I need the sit-down. The road from Dooneen gets longer every Friday, I swear, and the pain in my side’s more acidy than before. I should’ve spoken with Dr. Kumar, but what could she do if it’s my cancer waking up? There’s no CAT scans anymore, no drug regime. Molly Coogan, who used to design websites but who now grows apples in polytunnels up below Ardahill, and her husband, Seamus, are also at the table. As the Englishwoman there, I’m asked if I know anything about Hinkley Point, but I have to disappoint them.

Nobody else has had any luck with threading out of the island of Ireland for two or three days now. Pat Joe spoke with his cousin in Ardmore in East Cork last night, however, and holds court for a few minutes. Apparently two hundred Asylumites from Portugal landed on the beach in five or six vessels, and are now living in an old zombie estate built back in the Tiger Days. “As bold as you please,” says Pat Joe, nursing his soup, “as if they own the place, like. So the Ardmore town mayor, he leads a—a deputation up to the zombie estate, my cousin was one of them, to tell the Asylumites that, very sorry and all, but they can’t winter there, there’s not enough food in the Co-op or wood in the plantation for the villagers as it is, let alone two hundred extra mouths, like. This big feller walks out, takes out a gun, cool as you please, and shoots Kenny’s hat off his head, like in an old cowboy western!”

“Shocking! Shocking!” Betty Power is a theatrical matriarch who runs Kilcrannog’s smokehouse. “What did the mayor do?”

“Sent a messenger to the Stability garrison in Dungarvan, asking for assistance, like—only to be told their jeeps had no feckin’ diesel.”

“The Stabilityjeeps had no diesel?” asks Molly Coogan, alarmed.

Pat Joe purses his lips and shakes his head. “Not one drop. The mayor was told to ‘pacify the situation’ as best he could. Only how’s yer man s’posed to manage that when his deadliest weapon’s a feckin’ staple gun?”

“ Iheard,” says Molly Coogan, “that the Sun Yat-sen”—one of the Chinese superfrigates that accompanies the Chinese container ships on the polar route—“sailed into Cork Harbor last week with five hundred marines on deck. A bit of a show of force, like.”

“Sure you’re missing a zero, there, Moll,” says Fern O’Brien, who leans over from the next table. “My Jude’s Bill was on loading duty at Ringaskiddy that day so he was, and he swears there wasn’t a man under five t’ousandtrooping the color under the Chinese flag.”

I can imagine Ed, my long-dead partner, making hang-dog eyes at the authenticity of this so-called news but there’s more to come as talk switches to a sister-in-law of Pat Joe’s cousin in County Offaly, who knows a “Man in the Know” at Stability Research in the Dublin Pale who reckons the Swedes have genomed a rustproof, selffertile strain of wheat. “I’m only passing on what I’ve been told,” says Pat Joe, “but there’s talk of Stability planting it all over Ireland next spring. If people have full bellies, the Jackdawing and rioting’ll stop.”

“White bread,” sighs Sнnead Fitzgerald. “Imagine that.”

“I’d not want to go pissing on your snowman now, Pat Joe,” says Seamus Coogan, “but was that the same Man in the Know who said the Germans had a pill that cured Ratflu, or that the States was reunited again, and the president was sending airdrops of blankets, medicine, and peanut butter to all the NATO countries? Or was it that friend of a friend who met an Asylumite outside Youghal who swore on his mother’s life that he’d found a Technotopia where they still have twenty-four-hour electricity, hot showers, pineapples, and dark chocolate mousse, in Bermuda or Iceland or the Azores?”

I think about Martin’s remarks on imaginary lifeboats.

“I’m only passing on what I’ve been told,” sniffs Pat Joe.

“Whatever the future has in store,” says Betty Power, “we’re all in the hollow of God’s hand, so we are.”

“That’s certainly how Muriel Boyce sees it,” says Seamus Coogan.

“Martin’s doing his best,” says Betty Power, crisply, “but it’s clear that only the Church can take care of the devilry falling over the world.”

“Why will a loving God only help us if we vote for him?” asks Molly.

“You have to ask,” blinks Betty Power. “That’s how prayer works.”

“But Molly’s saying,” says Pat Joe, “why can’t He just answer our prayers directly? Why does he need us to vote for him?”

“To put the Church back where it belongs,” says Betty Power. “Guiding our country.”

The conversation heats up but I may as well be listening to children arguing about the acts and motives of Santa Claus. I’ve seen what happens after death, the Dusk and the Dunes, and it was as real to me as the chipped mug of tea in my hand. Perhaps the souls I saw were bound for an afterlife beyond the Last Sea, but if so, it’s not the afterlife described by any priest or imam. There is no God but the one we dream up, I could assure my fellow parishioners: Humanity is on its own and always was …

… but my truth sounds no crazier than their faith, no saner either; and who has the right to kill Santa? Specially a Santa who promises to reunite the Coogans with their dead son, Pat Joe with his dead brother, me with Aoife, Jacko, Mum, and Dad; and even put the Endarkenment into reverse, and bring back central heating, online ordering, Ryanair, and chocolate. Our hunger for our loved ones and our lost world is as sharp as grief; it howls to be fed. If only that same hunger didn’t make us so meekly vulnerable to men like Father Brady.

“Fallen pregnant?” Betty Power covers her mouth. “Never!” We’re back to Sheep’s Head gossip. I’d like to ask who’s pregnant, but if I do so at this point they’ll all wonder if I’m going deaf or turning senile.

“That’s the problem.” Sinйad Fitzgerald leans in. “Three lads went off with young Miss Hegarty after the harvest festival, they were all off their faces”—she mimes smoking a joint—“so until the baby’s features are clear enough to play Spot the Daddy, Damien Hegarty doesn’t know who to point the shotgun at. A proper mess it is.”

The Hegartys keep goats lower down the peninsula, between Ahakista and Durrus. “Shocking,” says Betty Power, “and Niamh Hegarty not a day over sixteen, too, am I right? No mother in the house to lay down the rules, that’s what this is about. They just think anything goes. Which is exactly why Father Brady’s—”

“Hear that,” says Pat Joe, holding up a finger and listening …

… cups are poised in midlift; sentences dangle; babies are shushed; nearly two hundred West Corkonians fall silent, all at once; and then let out a collective sigh of relief. It’s the Convoy: two armored jeeps, ahead of and behind the diesel tanker and the box truck. Inside the Cordon we still have tractors and harvesters, and Stability vehicles still drive on the old N71 to Bantry to service the garrisons and the depots, but these four shiny state-of-the-art vehicles rumbling up Church Lane are the only regular visitors to Kilcrannog. For anyone over Rafiq’s age, say, the sound evokes the world we knew. Back then, traffic was a “noise,” not a “sound,” but it’s different now. If you close your eyes as the Convoy arrives you can imagine it’s 2030, say, back when you had your own car and Cork was a ninety-minute drive away, and my body didn’t ache all the time, and climate change was only a problem for people who lived in flood-prone areas. Only I don’t close my eyes these days, because it hurts too much when I open them. We all go outside to watch the show. I take my pram. It’s not that I don’t trust the villagers not to steal from an old lady with two kids to raise, but you shouldn’t tempt hungry people.