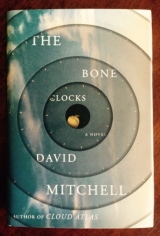

Текст книги "The Bone Clocks"

Автор книги: David Mitchell

Жанры:

Классическое фэнтези

,сообщить о нарушении

Текущая страница: 22 (всего у книги 40 страниц)

“If the archaeology falls through, there’s always natural history.”

Aoife smiles. “I Wikipediaed them five minutes ago.”

I ask, “Reckon they like apricots? There’s a squishy one left.”

Holly looks dubious. “What about ‘Do Not Feed the Animals’?”

“It’s not like we’re chucking them Cherry Ripe bars, Mum.”

“And surely,” I add, “if they’re endangered, they’ll need all the Vitamin C they can get.” I lob the apricot to within a few feet of the animal. It waddles over, sniffs, chomps, and looks up at us.

“ ‘Please, sir,’ ” Aoife does a trembly Oliver Twist voice, “ ‘can I have some more?’ How cuteis that? I’ve got to take a photo.”

“Not too close, love,” says her mother. “It’s a wild animal.”

“Gotcha.” Aoife walks down the slope, holding out her phone.

“What a well-raised kid,” I tell her mother, in a low voice.

She looks at me, and I see the signs of a full, fraught life around her eyes. If only she hadn’t written a book full of angel bollocks for gullible women disappointed with their lives, we could be friends. It’s a fair guess that Holly Sykes knows about my daughters and my divorce: the ex–Wild Child of British Letters may not be famous enough to sell books, but Zoл’s huge “I Will Survive” splash for the Sunday Telegraphgave the world a very one-sided version of our troubles. We watch Aoife feed the quokka, while all around us Rottnest’s bleached slopes buzz and whistle with insects, tinnitus-like. A lizard crosses the dust and …

The feeling of being watched comes back, stronger than ever. We aren’t the only ones here. There are lots. Near. I could swear.

Acacia tree to wiry shrub to shed-sized rock … Nobody.

“Do you feel them too?” Holly Sykes is watching me. “It’s an echo chamber, this place …”

If I say yes to this, I say yes to her whole flaky, nonempirical world. By saying yes to this, how do I refuse crystal healing, pastlife therapy, Atlantis, Reiki, and homeopathy? The problem is, she’s right. I do feel them. This place is … What’s another word for “haunted,” Mr. Novelist? My throat’s dry. My water bottle’s empty.

Down on the rocks blue breakers flume on rocks. I hear the boom, faint and soft, a second later. Further out, surfers at play.

“They were brought here in chains,” says Holly Sykes.

“Who were?”

“The Noongar. Wadjemup, they called this island. Means the Place Across the Water.” She sniffs. “For the Noongar, the land couldn’t be owned. No more than the seasons could be owned, or a year. What the land gave, you shared.”

Holly Sykes’s voice is flattening out and faltering, as if she’s not speaking but translating a knotty text. Or picking one voice out from a roaring crowd. “The djangacame. We thought they were dead ones, come back. They forgot how to speak when they were dead, so now they spoke like birds. Only a few came, at first. Their canoes were big as hills, but hollow, like big floating rooms made of many many rooms. Then more ships, more and more, every ship it puked up more, more, more of them. They planted fences, waved maps, brought sheep, mined for metals. They shot our animals, but if we killed their animals, they hunted us like vermin, and took the women away …”

This performance ought to be ridiculous. But in the flesh, three feet away, a vein pulsing in her temple, I don’t know what to make of it. “Is this a story you’re working on, Holly?”

“Too late, we understood, the djangawasn’t dead Noongar jumped up, they was Whitefellas.” Holly’s voice is blurring now. Some words go missing. “Whitefella made Wadjemup a prison for Noongar. F’burning bush, like we always done, Whitefella ship us to Wadjemup. F’fighting at Whitefella, Whitefella ship us to Wadjemup. Chains. Cells. Coldbox. Hotbox. Years. Whips. Work. Worst thing is this: Our souls can’t cross the sea. So when the prison boat takes us from Fremantle, our soul’s torn from out body. Sick joke. So when come to Wadjemup, we Noongar we die like flies.”

One in four words I’m guessing at now. Holly Sykes’s pupils have shrunk to dots as tiny as full stops. This can’t be right. “Holly?” What’s the first-aid response for this? She must be blind. Holly starts speaking again but not a lot’s in English: I catch “priest,” “gun,” “gallows,” and “swim.” I have zero knowledge of Aboriginal languages, but what’s battling its way out of Holly Sykes’s mouth now sure as hell isn’t French, German, Spanish, or Latin. Then Holly Sykes’s head jerks back and smacks the lighthouse and the word “epilepsy” flashes through my mind. I grip her head so that when she repeats the head-smash it only bashes my hand. I swivel upright and clasp her head firmly against my chest and yell, “Aoife!”

The girl reappears from behind a tree, the quokkas beat a retreat, and I call out, “Your mother’s having an attack!”

A few pounding seconds later, Aoife Brubeck’s here, holding her mother’s face. She speaks sharply: “Mum! Stop it! Come back! Mum!”

A cracked buzzing hum starts deep in Holly’s throat.

Aoife asks, “How long have her eyes been like that?”

“Sixty seconds? Less, maybe. Is she epileptic?”

“The worst’s over. It’s not epilepsy, no. She’s stopped talking, so she’s not hearing now, and—oh, shit—what’s this blood?”

There’s sticky red on my hand. “She hit the wall.”

Aoife winces and inspects her mother’s head. “She’ll have a hell of a lump. But, look, her eyes are coming back.” Sure enough, her pupils are swelling from dots to proper disks.

I note, “You’re acting as if this has happened before.”

“A few times,” replies Aoife, with understatement. “You haven’t read The Radio People, have you?”

Before I can answer Holly Sykes blinks, and finds us. “Oh, f’Chrissakes, it just happened, didn’t it?”

Aoife’s worried and motherly. “Welcome back.”

She’s still pasty as pasta. “What did I do to my head?”

“Tried to dent the lighthouse with it, Crispin says.”

Holly Sykes flinches at me. “Did you listen to me?”

“It was hard not to. At first. Then it … wasn’t exactly English. Look, I’m no first-aid expert, but I’m worried about concussion. Cycling down a hilly, bendy road would not be clever, not right now. I’ve got a number from the bike-hire place. I’ll ask for a medic to drive out and pick you up. I strongly advise this.”

Holly looks at Aoife, who says, “It’s sensible, Mum,” and gives her mother’s arm a squeeze.

Holly props herself upright. “God alone knows what you must think of all this, Crispin.”

It hardly matters. I tap in the number, distracted by a tiny bird calling Crikey, crikey, crikey …

FOR THE FIFTIETH time Holly groans. “I just feel so em barrassed.”

The ferry’s pulling into Fremantle. “ Pleasestop saying that.”

“But I feel awful, Crispin, cutting short your trip to Rottnest.”

“I’d have come back on this ferry, anyway. If ever a place had a karma of damnation, it’s Rottnest. And all those slick galleries selling Aborigine art were eroding away my will to live. It’s as if Germans built a Jewish food hall over Buchenwald.”

“Spot the writer.” Aoife finishes her ice pop. “Again.”

“Writing’s a pathology,” I say. “I’d pack it in tomorrow, if I could.”

The ferry’s engines growl, and cut out. Passengers gather their belongings, unplug earphones, and look for children. Holly’s phone goes and she checks it: “It’s my friend, the one who’s picking us up. Just a mo.” While she takes the call, I check my own phone for messages. Nothing since the picture of Juno’s birthday party earlier. Our international marriage was once a walk-in closet of discoveries and curiosities, but international divorce is not for the fainthearted. Through the spray-dashed window I watch lithe young Aussies leap from prow to quayside, tying ropes around painted steel cleats.

“Our friend’s picking us up from the terminal building.” Holly puts her phone away. “She’s got space for you too, Crispin, if you’d like a lift back to the hotel.”

I’ve got no energy to go exploring Perth. “Please.”

We walk down the gangway onto the concrete pier, where my legs struggle to adjust to terra firma. Aoife waves to a woman waving back, but I don’t zone in on Holly’s friend until I’m a few feet away.

“Hello, Crispin,” the woman says, as if she knows me.

“Of course,” remembers Holly. “You two met in Colombia!”

“I may,” the woman smiles, “have slipped Crispin’s mind.”

“Not at all, Carmen Salvat,” I tell her. “How are you?”

August 20, 2018

LEAVING THE AIR-CONDITIONED FOYER of the Shanghai Mandarin we plunge into a wall of stewy heat and adoration from a flash mob—I’ve never seen anything like this level of fandom for a literary writer. More’s the pity that writer isn’t me—as they recognize him, the cry goes up, “Neeeeeck!”Nick Greek, at the vanguard of our two-writer convoy, has been living in Shanghai since March, learning Cantonese and researching a novel about the Opium Wars. Hal the Hyena has liaised closely with his local agent and now a quarter of a million Chinese readers follow Nick Greek on Weibo. Over lunch he mentioned he’s been turning down modeling contracts, for sod’s sake. “It’s so embarrassing,” he said modestly. “I mean, what would Steinbeck have made of this?” I managed to smile, thinking how Modesty is Vanity’s craftier stepbrother. Some heavyweight minders from the book fair are having to widen a path through the throng of nubile, raven-haired, book-toting Chinese fans: “Neeck! Sign, please, please sign!” Some are even waving A4 color photos of the young American for him to deface, for buggery’s sake. “He’s a U.S. imperialist!” I want to shout. “What about the Dalai Lama on the White House lawn?” Miss Li, my British Council elf, and I follow in the wake of his entourage, blissfully unhassled. If I appear in any of the footage, they’ll assume I’m his father. And guess what, dear reader? It doesn’t matter. Let him enjoy the acclaim while it lasts. In six weeks Carmen and I will be living in our dream apartment overlooking the Plaza de la Villa in Madrid. When my old mucker Ewan Rice sees it he’ll be sosodding jealous he’ll explode in a green cloud of spores, even if he haswon the Brittan Prize twice. Once we’re in, I can divide my time more equally between London and Madrid. Spanish cuisine, cheap wine, reliable sunshine, and love. Love. During all those wasted years of my prime with Zoл, I’d forgotten how wonderful it is to love and to be loved. After all, what is the Bubble Reputation compared to the love of a good woman?

Well? I’m asking you a question.

MISS LI LEADS me into the heart of the Shanghai Book Fair complex, where a large auditorium awaits keynote speakers—the true Big Beasts of International Publishing. I can imagine Chairman Mao issuing his jolly-well-thought-out economic diktats in this very space in the 1950s; for all I know, he did. This afternoon the stage is dominated by a jungle of orchids and a ten-meter-high blowup of Nick Greek’s blond American head and torso. Miss Li leads me out through the other side of the large auditorium and on to my own venue, although she has to ask several people for directions. Eventually she locates it on the basement level. It appears to be a row of knocked-through broom cupboards. There are thirty chairs in the venue, though only seven are occupied, not counting myself. To wit: my smiling interviewer, an unsmiling female translator, a nervous Miss Li, my friendly Editor Fang, in his Black Sabbath T-shirt, two youths with Shanghai Book Fair ID tags still round their necks, and a girl of what used to be known as Eurasian extraction. She’s short, boyish, and sports a nerdy pair of glasses and a shaven head: electrotherapy chic. A droning fan stirs the heat above us, a striplight flickers a little, and the walls are blotched and streaked, like the inside of a never-cleaned oven. I am tempted to walk out—I really am—but handling the fallout would be worse than putting a brave face on the afternoon. I’m sure the British Council keeps a blacklist of badly behaved authors.

My interviewer thanks everyone for coming in Chinese, and gives what I gather is a short introduction. Then I do a reading from Echo Must Diewhile a Mandarin translation is projected onto a screen behind me. It’s the same section I read at Hay-on-Wye, three years ago. Sodding hell, is it already three years since I last published? Trevor Upward’s hilarious escapades on the roof of the Eurostar do not appear to amuse the select gathering. Was my satire translated as a straight tragedy? Or was the Hershey wit taken into custody at the language barrier? After my reading I endure the sound of fourteen hands clapping, take my seat, and help myself to a glass of sparkling water—I’m thirsty as hell. The water is flat and tastes of yeast. I hope it didn’t come out of a Shanghai tap. My interviewer smiles, thanks me in English, and asks me the same questions I’ve been asked since I arrived in Beijing a few days ago: “How does your famous father’s work influence your novels?”; “Why does Desiccated Embryoshave a symmetrical structure?”; “What truths should the Chinese reader find in your novels?” I give the same answers I’ve been giving since I arrived in Beijing a few days ago, and my spidery, unsmiling translator, who also translated my answers several times yesterday, renders my sentences into Chinese without any difficulty. Electrotherapy Girl, I notice, is actually taking notes. Then the interviewer asks, “And do you read your reviews?” which redirects my train of thought towards Richard Cheeseman where it smashes into last week’s miserable visit to Bogotб and comes off the tracks altogether …

HELL’S BELLS, THAT was one dispiriting visit, dear reader. Dominic Fitzsimmons had been pulling strings for months to get me and Richard’s sister Maggie a meeting with his Colombian counterpart at the Ministry of Justice for us to discuss the terms of repatriation—only for said dignitary to become “unavailable” at the last minute. A youthful underling came in his place—the boy was virtually tripping over his umbilical cord. He kept taking calls during our twenty-seven-minute audience, and twice he called meMeester Cheeseman while referring to “the Prisoner ’Earshey.” Waste of sodding time. The next day we visited poor Richard at the Penitenciarнa Central. He’s suffering from weight loss, shingles, piles, depression, and his hair’s falling out too, but there’s only one doctor for two thousand inmates, and in the case of middle-class European prisoners, the good medic requires a fee of five hundred dollars per consultation. Richard asked us to bring books, paper, and pencils, but he turned down my offer of a laptop or iPad because the guards would nick it. “It marks you as rich,” he told us, in a broken voice, “and if they know you’re rich they make you buy insurance.” The place is run by gangs who control the in-house drug trade. “Don’t worry, Maggie,” Richard told his sister. “I don’t touch the stuff. Needles are shared, they bulk out the stuff with powder, and once you owe them, they’ve got your soul. It’d kill off my chances of an early appeal.” Maggie stayed brave for her brother, but as soon as we were out of the prison gates, she sobbed and sobbed and sobbed. My own conscience felt hooked and zapped by a Taser. It still does.

But I can’t change places with him. It would kill me.

“Mr. Hershey?” Miss Li’s looking worried. “You okay?”

I blink. Shanghai. The book fair. “Yes, I just … Sorry, um, yes … Do I read my reviews? No. Not anymore. They take me to places I don’t wish to go.” As my interpreter gets to work on this, I notice that my audience is down to six. Electrotherapy Girl has slipped away.

THE SHANGHAI BUND is several things: a waterfront sweep of 1930s architecture with some ornate Toytown set pieces along the way; a symbol of Western colonial arrogance; a symbol of the ascension of the modern Chinese state; four lanes of slow-moving, or no-moving, traffic; and a raised promenade along the Huangpu River where flows a Walt Whitman throng of tourists, families, couples, vendors, pickpockets, friendless novelists, muttering drug dealers, and pimps: “Hey, mister, want drug, want sex? Very near, beautiful girls.” Crispin Hershey says, “No.” Not only is our hero loyally hitched, but he fears that the paperwork arising from getting Shanghaied in a Shanghai brothel would be truly Homeric, and not in a good way.

The sun disintegrates into evening and the skyscrapers over the river begin to fluoresce: there’s a titanic bottle opener; an outsize 1920s interstellar rocket; a supra-Ozymandian obelisk, plus a supporting cast of mere forty-, fifty-, sixty-floor buildings, clustering skywards like a doomed game of Tetris. In Mao’s time Pudong was a salt marsh, Nick Greek was telling me, but now you look for levitating jet-cars. When I was a boy the U.S.A. was synonymous with modernity; now it’s here. So I carry on walking, imagining the past: junks with lanterns swinging in the ebb and flow; the ghostly crisscross of masts and rigging, the groan of hulls laid down in Glasgow, Hamburg, and Marseille; hard, knotted stevedores unloading opium, loading tea; dotted lines of Japanese bombers, bombing the city to rubble; bullets, millions of bullets, bullets from Chicago, bullets from Fukuoka, bullets from Stalingrad, ratatat-tat-tat-tat. If cities have auras, like Zoл always insisted people do, if your “chakra is open,” then Shanghai’s aura is the color of money and power. Its emails can shut down factories in Detroit, denude Australia of its iron ore, strip Zimbabwe of its rhino horn, pump the Dow Jones full of either steroids or financial sewage …

My phone’s ringing. Perfect. My favorite person.

“Hail, O Face That Launched a Thousand Ships.”

“Hello, you idiot. How’s the mysterious Orient?”

“Shanghai’s impressive, but it lacks a Carmen Salvat.”

“And how was the Shanghai International Book Fair?”

“Ah, same old, same old. A good crowd at my event.”

“Great! You gave Nick a run for his money, then?”

“ ‘Nick Greek’ to you,” growls my green-eyed monster. “It’s not a popularity contest, you know.”

“Good to hear you say so. Any sign of Holly yet?”

“No, her flight’s not due in until later—and, anyway, I’ve snuck off from the hotel to the Bund. I’m here now, skyscraper-watching.”

“Amazing, aren’t they? Are they all lit up yet?”

“Yep. Glowing like Lucy andthe Sky andDiamonds. So much for my day, how was yours?”

“A sales meeting with an anxious sales team, an artwork meeting with a frantic printer, and now a lunch meeting with melancholic booksellers, followed by crisis meetings until five.”

“Lovely. Any news from the letting agent?”

“Ye-es. The news is, the apartment’s ours if we—”

“Oh that’s fantastic, darling! I’ll get on to the—”

“But listen, Crisp. I’m not quite as sure about it as I was.”

I stand aside for a troop of cheerful Chinese punks in full regalia. “The Plaza de la Villa flat? It was far and a waythe best place we saw. Plenty of light, space for my study, just about affordable, and please—when we lift the blinds every morning, it’ll be like living over a Pйrez-Reverte novel. I don’t understand: What boxes isn’t it ticking?”

My editor-girlfriend chooses her words with care. “I didn’t realize how attached I am to having my own place, until now. My place here is my own little castle. I like the neighborhood, my neighbors …”

“But, Carmen, your own little castle is little. If I’m to divide my time between London and Madrid, we need somewhere bigger.”

“I know … I just feel we’re rushing things a bit.”

That sinking feeling. “It’s been a year since Perth.”

“I’m not rejecting you, Crispin, honestly. I just …”

Evening in Shanghai is turning suddenly cooler.

“I just … want to carry on as we are for a while, that’s all.”

Everyone I see appears to be one half of a loving couple. I remember this I’m not rejecting you, Crispinfrom my pre-Zoл era, when it marked the beginning of breakups. Resentment snarls through the letterbox, feeding me lines to say: “Carmen, make your sodding mind up!”; “Do you knowhow much we’re wasting on airfares?”; even, “Have you met someone else? Someone Spanish? Someone closer to your own age?”

I tell her, “That’s fine.”

She listens to the long pause. “It is?”

“I’m disappointed, but only because I don’t have enough money to buy a place near yours, so we could establish some sort of Hanseatic League of Little Castles. Maybe if a film deal for Echo Must Diefalls from the skies. Look, this call’s costing you a fortune. Go and cheer up your booksellers.”

“Am I still welcome in Hampstead next week?”

“You’re always welcome in Hampstead. Any week.”

She’s smiling in her office in Madrid, and I’m glad I didn’t listen to the snarls through the letterbox. “Thanks, Crispin. Give my love to Holly, if you meet up. She’s hoping to. And if anyone offers you the deep-fried durian fruit, steer clear. Okay, bye then—love you.”

“Love you too.” And end call. Do we use the L-word because we mean it, or because we want to kid ourselves into thinking we’re still in that blissful state?

BACK IN HIS hotel room on the twenty-ninth floor, Crispin Hershey showers away his sticky day and flumps back onto his snowy bed, clad in boxers and a T-shirt emblazoned with Beckett’s “fail better” quote I was given in Santa Fe. Dinner was a gathering of writers, editors, foreign bookshop owners, and British Council folks at a restaurant with revolving tables. Nick Greek was on eloquent form, while I imagined him dying in spectacular fashion, facedown in a large dish of glazed duck, lotus root, and bamboo shoot. Hercule Poirot would emerge from the shadows to tell us who had poisoned the rising literary star, and why. The older writer would be an obvious choice, with professional jealousy as a motive, which is why it couldn’t be him. I stare at the digital clock in the TV-screen frame: 22:17. Thinking about Carmen, I shouldn’t be surprised at her reticence re: Our Flat. The “Honeymoon Over” signs were already there. She refused to be in London when Juno and Anaпs came over last month. The girls’ visit was not a wholly unqualified success. On the way from the airport, Juno announced she was not into horses anymore so, of course, Anaпs decided that she was too old for pony camp as well, and as the deposit was nonrefundable, I expressed my displeasure perhaps a tad too much in the manner of my own father. Five minutes later Anaпs was bawling her eyes out and Juno was studying her nails, telling me, “It’s no good, Dad, you can’t use twentieth-century methods on twenty-first-century kids.” It cost me five hundred pounds and three hours in Carnaby Street boutiques to stop them phoning their mother to get their flights back to Montreal rebooked for the next day. Zoл lets Juno get away with rejecting even the gentlest admonishment with a virulent “Oh, whatever!” while Anaпs is turning into a sea anemone whose mind sways whichever way the currents of the moment push her. The visit would have gone better if Carmen had pitched in, but she wasn’t having any of it: “They don’t need a stepmother laying down the law when holidaying in London with their dad.” I said I felt a deep affection for my own stepmother. Carmen replied that after reading my memoir about Dad she could quite understand why. Subject deftly changed.

Classic Carmen Salvat strategy, that.

22:47. I PLAY chess on my iPhone, and indulge in a fond fantasy that my opponent isn’t a mind of digital code but Dad: It’s Dad’s attacks I repel; Dad’s defenses I dismantle; Dad’s king scurrying around the board to prolong the inevitable. Stress will out, however; usually I win at this level, but today I keep making repeated slips. Worse, the old git starts taking the piss: “Superb strategy, Crisp; that’s it, you move your rook there; so I’ll move my knight here; pincer your dozy rook against your blundering queen and now there’s Sweet Fanny Adams you can do about it!” When I use the undo function to take back my rook, Dad crows: “That’s right—ask a sodding machine to bail you out. Why not download an app to write your next novel?” “Sod off,” I tell him, and turn off my phone. I switch on the TV and sift through the channels until I recognize a scene from Mike Leigh’s film One Year. It’s appallingly good. My own dialogue is shite compared to this. Sleep would be a good idea, but I’m at the mercy of jet lag and I find I’m wired. My stomach isn’t too sure about the deep-fried chunks of durian fruit, either; Nick Greek admitted to the British consul that he hadn’t yet acquired the taste, so I ate three. I’d love a smoke but Carmen’s bullied me into quitting so, yummy yummy, it’s a zap of Nicorette. Richard Cheeseman’s smoking again. How can he not, stuck where he is, poor bastard? His teeth are brown as tea. I flick through more channels and find a subtitled American import, The Dog Whisperer, about an animal trainer who sorts out psychotic Californians’ psychotic pets. 23:10. I consider jerking off again, purely for medicinal purposes, and browse my mental Blu-ray collection, settling on the girl from that commune Rivendell somewhere in West London—but decide that I can’t be bothered. So I open my new Moleskine, turn to the first page, and write “The Rottnest Novel” at the top …

… and find I’ve forgotten my main character’s name again. Bugger it. For a while he was Duncan Frye, but Carmen said that sounded like a Scottish chip-shop owner. So I went with “Duncan McTeague” but the “Mc” is too obvious for a Scot. I’ll settle with Duncan Drummond, for now. DD. Duncan Drummond, then, an 1840s stonemason who ends up in the Swan River Settlement, designs a lighthouse on Rottnest Island. Hyena Hal isn’t sure about this book—“Certainly a fresh departure, Crisp”—but I woke up one morning and realized that all my novels deal with contemporary Londoners whose upper-middle-class lives have their organs ripped out by catastrophe or scandal. Diminishing returns were kicking in even before Richard Cheeseman’s review, I fear. Already, however, a few problemettes with the Rottnest novel are mooning their brown starfishes my way: Viz., I’ve only got three thousand words; those three thousand are not the best of my career; my final new deadline is December 31 of this year; Editor Oliver has been sacked for “underperformance” and his aptly named successor Curt is making some unpleasant noises about paying back advances.

Would a quokka or two spice it up? I wonder.

Sod this. There must be a bar open somewhere.

HALLELUJAH! I WALK into the Sky High bar on the forty-third floor and it’s still open. I sink my weary carcass into an armchair by the window and order a twenty-five-dollar shot of cognac. The view is to die for. Shanghai by night is a mind of a million lights: of orange dot-to-dots along expressways, of pixel-white headlights and red taillights; green lights on the cranes; blinking blues on airplanes; office blocks across the road, and smearages of specks, miles away, every microspeck a life, a family, a loner, a soap opera; floodlights up the skyscrapers over in Pudong; closer up, animated ad-screens for Omega, Burberry, Iron Man 5, gigawatt-brite, flyposted onto night’s undarkness. Every conceivable light, in fact, except the moon and stars. “There’s no distances in prisons,” Richard Cheeseman wrote, in a letter to our Friends Committee. “No outside windows, so the furthest I ever see is the tops of the walls around the yard. I’d give a lot just for a view of a few miles. It wouldn’t have to be pretty—urban grot would be fine—so long as there was several miles’ worth.”

And Crispin Hershey had put him there.

Crispin Hershey keeps him there.

“Hello, Mr. Hershey,” says a woman. “Fancy finding you here.”

I jump up with unexpected vigor. “Holly! Hi! I was just …” I’m not sure how to finish my sentence so we kiss, cheek to cheek, like fairly good friends. She looks tired, which is only to be expected for a time-zone hopper, but her velvet suit looks great on her—Carmen’s taken her shopping a few times. I indicate an imaginary companion in the third chair: “Do you and Captain Jetlag know each other?”

She glances at the chair. “We go back a few years, yes.”

“When did you get in from—was it Singapore?”

“Um … Got to think. No, Jakarta. It’s Monday, right?”

“Welcome to the Literary Life. How’s Aoife?”

“Officially in love.” Holly’s smile has several levels to it. “With a young man called Цrvar.”

“Цrvar? From which galaxy do Цrvars hail?”

“Iceland. Aoife went there a week ago, to meet the folks.”

“Lucky Aoife. Lucky Цrvar. Do you approve of the young man?”

“As it happens, yes. Aoife’s brought him down to Rye a few times. He’s doing genetics at Oxford, despite his dyslexia, don’t ask me how that works. He fixes things. Shelves, shower doors, a stuck blind.” Holly asks the waitress who brings my cognac for a glass of the house white. “What about Juno?”

“Juno? Never fixed a sodding thing in her life.”

“No, you dope! Is Juno dating yet?”

“Oh. That. No, give her a chance, she’s only fifteen. Mmm. Did you discuss boys with your father at that age?”

Holly’s phone bleeps. She glances at it. “It’s a message for you, from Carmen: ‘Tell Crispin I told him not to eat the durian fruit.’ Does that make any sense?”

“It does, alas.”

“Will you be moving into that new place in Madrid?”

“No. It’s a bit of a long story.”

“ROTTNEST?” HOLLY FLICKS her wineglass with her fingernail, as if testing its note. “Well, as Carmen may have mentioned, at various points in my life, I’ve heard voices that other people didn’t hear. Or I’ve been sure about things that I had no way of knowing. Or, occasionally, been the mouthpiece for … presences that weren’t me. Sorry that last one sounds seancey, I can’t help it. And unlike a seance, I don’t summon anything up. Voices just … nab me. I wish they didn’t. I wish very badly that they didn’t. But they do.”

I know all this. “You’ve got a degree in psychology, right?”

Holly sees the subtext, takes off her glasses, and pinches the indented mark on her nose. “Okay, Hershey, you win. Summer of 1985. I was sixteen. Jacko had been missing for twelve months. Me and Sharon were staying at Bantry in County Cork, with relatives. One wet day we were playing snakes and ladders with the smallies, when”—three decades later, Holly flinches—“I knew, or heard, or ‘felt a certainty,’ whatever you want to call it, what number the dice was next going to land on. My cousin’d rattle the eggcup and I’d think, Five. Lo and behold, the die landed on five. One. Five. Three. On and on. A lucky streak, right? Happens all the time. But on it went. For over fifty throws, f’Chrissakes. I wanted it to stop. Each time I thought, This time it’ll be wrong and I’ll be able to dismiss it all as a coincidence … but on and on it went, till Sharon needed a six to win, which I knew she’d roll. And she did. By now, I had a cracking headache, so I crawled off to bed. When I woke up, Sharon and our cousins were playing Cluedo, and everything was back to normal. And straightaway I started persuading myself that I’d only i magined knowing the numbers. By the time I got back to boring old Gravesend, I’d half persuaded myself the whole thing’d just been just a … a one-off weirdness I was probably misremembering.”