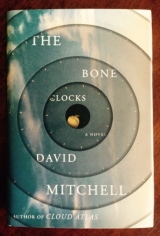

Текст книги "The Bone Clocks"

Автор книги: David Mitchell

Жанры:

Классическое фэнтези

,сообщить о нарушении

Текущая страница: 12 (всего у книги 40 страниц)

THE FRACAS IN the lounge falls silent. “ You, whoever you are,” shouts Rufus Chetwynd-Pitt, “get off my property nowor I call the police!”

Camp-Psycho-German with a nasal voice: “You ate in a fancy restaurant, boys. Now it is the time to pay the bill.”

Chetwynd-Pitt: “They never saidthey were hookers!”

Camp-Psycho-German: “ Youdid not say you are crafted of penis yogurt, yet you are. You are Rufus, I believe.”

“None of your fuckingbusiness whatmy—”

“Disrespectful language is unbusinesslike, Rufus.”

“Get—out—now!”

“Unfortunately, you owe three thousand dollars.”

Chetwynd-Pitt: “Really? Let’s see what the police—”

That must be the TV expiring in a tinkly boom. The bookcase slams on the stone wall? Smash, clang, wallop: glassware, crockery, pictures, mirrors; surely Henry Kissinger won’t escape unscathed. And there’s Chetwynd-Pitt shrieking, “My hand, my f’ck’n’ hand!”

An inaudible answer to an inaudible question.

Camp-Psycho-German: “I CANNOT HEAR YOU, RUFUS!”

“We’ll pay,” whinnies Chetwynd-Pitt, “we’ll pay …”

“Certainly. However, you obliged Shandy to call us, so the price is higher. This is a ‘call-out fee’ in English, I think. In business, we must cover costs. You. Yes, you. What is your name?”

“O-O-Olly,” says Olly Quinn.

“My second wife owned a Chihuahua named Olly. It bit me. I threw it down a … Scheiss, what is it, for an elevator to go up, to go down? The big hole. Olly—I am asking you the English word.”

“A … an elevator shaft?”

“Precisely. I threw Olly into the elevator shaft. So, Olly, you will not bite me. Correct? So. You will now gather your monies.”

Quinn says, “My—my—my what?”

“Monies. Funds. Assets. Yours, Rufus’s, your friend’s. If there is enough to pay our call-out fee, we leave you to your Happy New Year. If not, we do some lateral thinking about how you pay your debts.”

One of the women speaks, and more mumbling. A few seconds later Camp-Psycho-German calls up the stairway. “Beatle Number Four! Join us. You will not be hurt, if you do no heroic actions.”

Soundlessly, I open the window—it’s cold!—and swing my legs over the window ledge. A Hitchcock Vertigomoment: Alpine roofs you’re planning to slide down look suddenly much steeper than Alpine roofs admired from below. Although the angle of Chetwynd-Pitt’s chalet becomes shallower over the kitchen, there’s a real risk that in fifteen seconds I’ll be the screaming owner of two broken legs.

“Lamb?” It’s Fitzsimmons, up on the stairway. “That money you won off Rufus … He needs it. They have knives, Hugo. Hugo?”

I lower myself onto the tiles, gripping the windowsill.

Five, four, three, two, one …

LE CROC IS locked, dark, and there’s no sign of Holly Sykes. Perhaps the bar’s closed tonight, so Holly won’t be in to clean it until tomorrow morning. Why didn’t I ask for her number? I hobble to the town square but even the hub of La Fontaine Sainte-Agnиs is in an end-of-the-world mood: few tourists, fewer vehicles, the gorilla– cr к pie’s nowhere to be seen, most shops have Ferm йsigns up. How come? Last year January 1 had quite a buzz. The sky presses lower, the gray of sodden mattresses. I go into La Pвtisserie Palanche de la Cretta, order a coffee and a carac, and slump in the corner by the window, ignoring my throbbing ankle. Detective Sheila Young won’t be thinking about me today, at least. What now? What next? Activate Marcus Anyder? I have his passport in a safety-deposit box at Euston station. A bus to Geneva, a train to Amsterdam or Paris; across on the hovercraft; flight to Panama; the Caribbean … Job on a yacht.

Really? Do I pack in my old life, just like that?

Never see my family again? It’s so abrupt.

Somehow this isn’t what the script says.

Olly Quinn passes the window, just three feet and a pane of glass away, accompanied by a cheerful-looking man in a sheepskin jacket. Camp-Psycho-German’s right hand, I presume. Quinn looks pale and sick. The duo march past the phone box where our Olly had his Ness-based meltdown only yesterday and into Swissbank’s automated lobby where the cashpoints live. Here Quinn makes three withdrawals with three different cards, before being frog-marched back. I hide behind a conveniently to-hand newspaper. A Normal would feel guilt or vindication; I feel as if I just watched a middle-of-the-road episode of Inspector Morse.

“Morning, Poshboy,” says Holly, holding a hot chocolate. She’s beautiful. She’s utterly herself. She’s got a red beret. She’s perceptive. “So, what sort of trouble are you in?”

I don’t know why I deny it. “Everything’s fine.”

“Can I sit down, or are you expecting company?”

“Yes. No. Please. Sit down. No company.”

She removes her ski jacket, the mint-green one, sits opposite me, places her red beret on the table, unwinds her cream scarf from her neck, rolls it up into a ball, and places it on her beret.

“I just went to the bar,” I admit, “but figured you were skiing.”

“The slopes are shut. Because of the blizzard.”

I glance outside again. “What blizzard?”

“You really should listen to the local radio.”

“There’s only so much ‘One Night in Bangkok’ a man can take.”

She stirs her hot chocolate. “You ought to be getting back—the forecast’s for whiteout conditions, within the hour. You can’t see three yards in a whiteout. It’s like being blinded.” She eats a spoonful of froth and waits for me to confess what sort of trouble I’m in.

“I just checked out of the Hotel Chetwynd-Pitt.”

“I’d check in again, if I were you. Really.”

I do a downed-plane hum. “Problematic.”

“Unhappy families in the House of Rufus Sexist-Git?”

I lean forward. “Their hot totties from Club Walpurgis turned out to be prostitutes. Their pimps are extracting every last centime they can scare out of them as we speak. I exited via an escape hatch.”

Holly shows no surprise at this common ski-resort tale. “So what’s your plan?”

I look into her serious eyes. A dum-dum bullet of happiness tears through my innards. “I don’t know.”

She sips her hot chocolate and I wish I was it. “You don’t look as worried as I would be, if I was in your shoes.”

I sip my own coffee. A pan hisses in the bakery kitchen. “I can’t explain it. It’s … impending metamorphosis.” I can see she doesn’t understand, and I don’t blame her. “Do you ever … know stuff, Holly? Stuff that you cannot possibly know, yet … Or—or lose hours. Not as in, ‘Wow, time flies,’ but as in,” I click my fingers, “there, an hour’s gone. Literally, between one heartbeat and the next. Well, maybe the time thing’s a red herring, but I knowmy life’s changing. Metamorphosis. That’s the best word I’ve got. You’re doing a good job of not looking freaked, but I must sound utterly, utterly, utterly bonkers.”

“Three too many utterlies. I work in a bar, remember.”

I fight a strong urge to lean over and kiss her. She’d slap me away. I feed my coffee a sugar lump. Then she asks, “Where do you plan to stay during your ‘metamorphosis’?”

I shrug. “ It’shappening to me. Not me to it.”

“Which sounds cool, but it hardly answers my question. The buses out aren’t running and the hotels are full.”

“Like I said, it’s a very poorly timed blizzard.”

“There’s other stuff you’re not telling me, isn’t there?”

“Oh, tons of stuff. Stuff I’ll never tell anyone, probably.”

Holly looks away, making a decision …

WHEN WE LEFT the town square there were just a few scratchy snowflakes prowling at roof height, but a hundred yards and a couple of corners later it’s as if the vast nozzle of an Alp-sized pump is blasting godalmighty massive coils of snow up the valley. Snow’s up my nose, snow’s in my eyes, snow’s in my armpits, snow howls after us through a stone archway into a grotty yard with dustbins already half buried under snow, snow, snow. Holly fumbles with the key and then we’re in, snow gusting through the gap and the wind whoo-whooingafter us until she slams the door shut, and it’s suddenly very peaceful. A short hallway, a mountain bike, stairs going up. Holly’s cheeks are hazed dark pink. Too skinny; if I were her mum I’d get a few fattening desserts down her. We take off our coats and boots and she gestures me up the carpeted stairs first. Above, there’s a light, airy flat with paper lampshades and varnished floorboards that squeak. Holly’s flat’s plainer than my rooms at Humber, and obviously 1970s, not 1570s, but I envy her it. It’s tidy and very sparsely furnished: The big room has an ancient TV and VHS player, a hand-me-down sofa, a beanbag, a low table, a neat pile of books in a corner, and that’s a near-complete inventory. The kitchenette, too, is minimalist: a single plate, dish, cup, knife, fork, and spoon wait on the drainer. Rosemary and sage grow in pots on a shelf. The top three smells are toast, cigarettes, and coffee. The only nod to ornament is a small oil painting of a pale blue cottage on a green slope over a silver ocean. Holly’s large window must offer an amazing view, but today it’s obscured by a blizzard, like white-noise static on an untuned telly. “It’s unbelievable,” I say. “All that snow.”

“It’s a whiteout.” She fills the kettle. “They happen. What did you do to your ankle? You’re limping.”

“I left my old accommodation а la Spiderman.”

“And landed а la sack-of-Spudsman.”

“My Scout pack did the Leaping from Buildings to Escape Violent Pimps badge the week I was away.”

“I’ve got some stretchy bandages you can borrow. But first …” She opens the door of a box room with one window as big as a shoebox lid. “My sister slept here okay, with the sofa cushions and blankets.”

“It’s warm, it’s dry.” I dump my bag inside. “It’s great.”

“Good. I sleep in my room, you sleep here. Yep?”

“Understood.” When a woman is interested in you, she’ll let you know; if not, there’s no aftershave, gift, or line you can spin to make her change her mind. “I’m grateful, Holly. God only knows what I would have done if you hadn’t taken pity on me.”

“You’d have survived. Your sort always does.”

I look at her. “My sort?”

She huffs through her nose.

“F’CHRISSAKES, LAMB, bandageit, it’s not a tourniquet.” Holly is less than impressed by my first aid skills. “Obviously you missed the Junior Doctor badge too. What badges didyou get? No, forget I asked. All right,” she puts down her cigarette, “I’ll do it—but if you make any idiotic nurse jokes, your other ankle gets cracked with a breadboard.”

“Definitely no nurse jokes.”

“Foot on the stool. I’m not kneeling at your feet.”

She unravels my cack-handed attempt, tutting at my ineptitude. My sockless swollen foot looks alien, naked, and unattractive against Holly’s fingers. “Here, rub in some arnica cream first—it’s pretty miraculous for swellings and bruises.” She hands me a tube. I obey, and when my ankle’s shiny she wraps the bandage around my foot with just the right degree of pressure and support. I watch her fingers, her loopable black hair, how her face hides and shows her inner weather. This isn’t lust. Lust wants, does the obvious, and pads back into the forest. Love is greedier. Love wants round-the-clock care; protection; rings, vows, joint accounts; scented candles on birthdays; life insurance. Babies. Love’s a dictator. I knowthis, yet the blast furnace in my ribcage roars You You You You You Youjust the same, and there’s bugger-all I can do about it. The wind attacks the window. “It’s not too tight?” asks Holly.

“It feels perfect,” I tell her.

“LIKE SNOW IN a snow globe,” Holly says, watching the blizzard. She tells me about UFO hunters who come to Sainte-Agnиs, which somehow leads on to working as a strawberry picker in Kent and a grape-picker in Bordeaux; why the Troubles in Northern Ireland won’t end without desegregated schools; how she once skied through a valley three minutes before an avalanche swept through. I light a cigarette and talk about how a bus I missed in Kashmir skidded off the Ladakh road and fell five hundred feet; why townies in Cambridge hate students; why roulette wheels have a zero; how great it is to row on the Thames at six A.M. in the summer. We discuss the first singles we bought, The Exorcistversus The Shining, planetariums and Madame Tussaud’s. We spout a lot of rubbish, but watching Holly Sykes talk is a fine thing. I empty the ashtray again. She quizzes me about my three months’ study program at Blithewood College in upstate New York. I give her the edited highlights, including getting shot at by a hunter who thought I was a deer. She tells me about her friend Gwyn, who worked last year at a summer camp in Colorado. I tell her about how Bart Simpson phones Marge from his summer camp and declares, “I’m no longer afraid of death,” but Holly asks who Bart Simpson is, so I have to explain. Holly talks about the band Talking Heads, like a Catholic discussing her favorite saints. The morning’s gone, we realize. Using a half bag of flour and bits and pieces from her fridge I make us a pizza, which I can tell impresses her more than she lets on. Aubergine, tomatoes, cheese, pesto, and Dijon mustard. There’s a bottle of wine in the fridge, too, but I serve us water in case she thinks I want to get her drunk. I ask if she’s a vegetarian, having noticed that even the stock cubes are veggie. She is, and she tells me how when she was sixteen she was at her great-aunt Eilнsh’s house in Ireland, “and this ewe walked by, bleating, and I realized, ‘Sweet fecking hell, I’m eating its children!’ ” I remark how people are superb at not thinking about awkward truths. After I’ve done the dishes—“to pay my rent”—I discover she’s never played backgammon, so I make us a board using the inside of a Weetabix box and a marker. She finds a pair of dice in a jar in a drawer, and we use silver and copper coins for pieces. By the third game she’s good enough for me to plausibly let her win.

“Congratulations,” I tell her. “You’re a fast learner.”

“Ought I to thank you for letting me beat you?”

“Oh no I didn’t! Seriously, you beat me fair and—”

“And you’re a virtuoso liar, Poshboy.”

LATER, WE TRY the TV but the reception’s affected by the storm and the screen’s as blizzardy as the window. Holly finds a black-and-white film on a videotape inherited from the flat’s last tenant. She stretches out on the sofa, I’m sunk into the beanbag, and the ashtray’s balanced on the arm between us. I try to focus on the film and not her body. The film’s British and made, I guess, in the late 1940s. Its opening minutes are missing so we don’t know the title, but it’s quite compelling, despite the Noлl Cowardy diction. The characters are on a cruise liner crossing some foggy expanse, and it takes a while for the passengers, Holly, and me to twig that they’re all dead. Each character gets deepened by a backstory—a good Chaucerian mix—before a magisterial Examiner arrives to decide each passenger’s fate in the afterlife. Ann, the saintly heroine, gets a pass into heaven, but her husband, Henry, the Austrian-pianist-resistance-fighter hero, killed himself—head in a gas cooker—and has to work as a steward aboard a similar ocean liner between the worlds. The wife tells the Examiner she’ll exchange heaven to be with her husband. Holly snorts. “Oh, please!” Ann and Henry then hear the sound of breaking glass and wake up in their flat, saved from the gas by the fresh air flooding in through the broken windows. String crescendo, man and wife embrace each other and a new life. The End.

“What a pile of pants,” says Holly.

“It kept us watching.”

The window’s dim mauve except for snowflakes tumbling near the glass. Holly gets up to draw the curtains but stands there, under the spell of the snow. “What’s the stupidest thing you’ve ever done, Poshboy?”

I fidget in my beanbag. It rustles. “Why?”

“You’re so megaconfident.” She draws the curtains and turns around, almost accusingly. “Rich people are, I s’pose, but you’re up on a different level. Do you never do stupid things that make you cringe with embarrassment—or shame—when you look back?”

“If I worked through the hundreds of stupid things I’ve done, we’d still be here next New Year’s Day.”

“I’m only asking for one.”

“Okay, then …” I guess she wants a flash of vulnerable underbelly—it’s like that witless interview question, “What’s your worst fault?” What have I done that’s stupid enough to qualify as a proper answer, but not so morally repugnant (а la Penhaligon’s Last Plunge) that a Normal would recoil in horror? “Okay. I’ve got this cousin, Jason, who grew up in this village in Worcestershire called Black Swan Green. One time, I’d have been about fifteen, my family was visiting, and Jason’s mum sent Jason and me to the village shop. He was younger than me and, as they say, ‘easily led.’ As his sophisticated London cousin, how did I amuse myself? By stealing a box of cigarettes from his village shop, luring poor Jason into the woods, and telling him that to fix his picked-on, shitty life, he had to learn to smoke. Seriously. Like the villain in some antismoking campaign. My meek cousin said, ‘Okay,’ and fifteen minutes later he was kneeling on the grass at my feet, vomiting up everything he’d eaten in the previous six months. There. One stupid, cruel act. My conscience goes ‘You bastard’ whenever I think of it,” I wince to hide my fib, “and I think, Sorry, Jason.”

Holly asks, “Does he smoke now?”

“I don’t believe he’s ever smoked.”

“Perhaps you inoculated him that day.”

“Perhaps I did. Who got you smoking?”

“OFF I WENT, across the Kent marshes. No plan. Just …” Holly’s hand gestures at the rolling distance. “The first night, I slept in a church in the middle of nowhere and … that was when it happened. That was the night Jacko disappeared. Back at the Captain Marlow he had his bath, Sharon read to him, Mam said good night. Nothing seemed wrong—apart from the fact that I’d gone off. After shutting up the pub, Dad went into Jacko’s room as usual to switch his radio off—that’s how he used to fall asleep, listening to foreign voices chuntering away. But, come Sunday morning, Jacko wasn’t there. He wasn’t in the pub. Like some crappy whodunnit puzzle, the doors were locked from the inside. At first the cops—Mam and Dad, even—thought I’d hatched a plot with Jacko, so it was only when …” Holly pauses to stabilize herself, “… I was tracked down, on the Monday afternoon, on this fruit farm on the Isle of Sheppey where I’d blagged a job as a picker, only then did the police start a proper search. Thirty-six hours later. First it was dogs and a radio appeal …” Holly rubs her palm around her face, “… then chains of locals combing wasteland around Gravesend, and police divers checking the … y’know, the obvious places. They found nothing. No body, no witnesses. Days went by, all the leads fizzled out. My parents shut the pub for weeks, I didn’t go to school, Sharon was crying the whole time …” Holly chokes. “You’d pray for the phone to go, then when it did, you’d be too scared it’d be bad news to pick it up. Mam shriveled up, Dad … He was always joking, before it happened. Afterwards, he was … like … hollow. I didn’t go out for weeks and weeks. Basically I left school. If Ruth, my sister-in-law, hadn’t weighed in, taken over, got Mam to go over to Ireland in the autumn, I honestly don’t think Mam’d still be alive. Even now, six years later, it’s still … Terrible to say, but now when I hear on the news about some murdered kid, I think, That’s hell, that’s your worst nightmare, but at least the parents know. At least they can grieve. We can’t. I mean, I knowJacko would’ve come back if he could’ve done, but unless there’s proof, unless there’s a”—Holly’s voice catches—“a body, your imagination never shuts up. It says, What if this happened? If that happened? What if he’s still alive somewhere in some psycho’s basement praying that today’s the day you find him?But even that’snot the worst part …” She looks away so I can’t see her face. There’s no need to tell her to take her time, even though, unbelievably, her travel clock on the shelf says it’s nine forty-five P.M. I light her a cigarette and put it in her fingers. She fills her lungs and slowly empties them. “If I hadn’t run off that weekend—over some stupid fucking boyfriend—would Jacko’ve let himself out of the Captain Marlow that night?” Still turned away, Holly rubs her face. “No. The answer’s no. Which means it’s my fault. Now my family tell me that’s not true, this counselor I went to told me the same, everybody says it. But they don’t have that question– Was it myfault?—drilling into their heads every hour, every day. Or the answer.”

The wind hammers out mad organist’s chords.

“I don’t know what to say, Holly …”

She finishes her glass of white wine.

“… except ‘Stop it.’ It’s rude.”

She turns to me, her eyes red, her face shocked.

“Yes,” I say. “Rude. It’s rude to Jacko.”

Obviously nobody’s ever said this to her.

“Switch places. Suppose Jacko had stormed off somewhere; suppose you’d gone looking for him, but some … evil overtook you and stopped you ever returning. Would you want Jacko to spend his life as self-blame junkie because once, one day, he committed a thoughtless action and made you worry about him?”

Holly looks as if she can’t quite believe I’m daring to say this. Actually, I can’t either. She’s thisfar from kicking me out.

“You’d want him to live fully,” I go on. “Wouldn’t you? To live morefully, not less. You’d need him to live your life for you.”

The VCR chooses now to trundle out its videotape. Holly’s voice comes out serrated: “So I’m s’posed to act like it never happened?”

“ No. But stop beating yourself up because you failed to see how a seven-year-old kid might respond to your ordinary act of teenage rebellion in 1984. Stop burying yourself alive at Le Croc of Shit. Your penance isn’t helping Jacko. Of course his disappearance has changed your life—how could it not?—but why does that make it right to squander your talents and the bloom of your youth serving cocktails to the likes of Chetwynd-Pitt and for the enrichment of the likes of Gьnter the employee-shagging drug dealer?”

Holly snaps back, “What am I s’posedto do, then?”

“ Idon’t know, do I? I haven’t had to survive what you’ve had to survive. Though, since you ask, there are countless other Jackos in London you couldhelp. Runaways, homeless teenagers, victims of God only knows what. You’ve told me a lot today, Holly, and I’m honored, even if you think I’m betraying your trust by talking to you like this. But I haven’t heard one thingthat forfeits your right to a useful and, yeah, even a content life.”

Holly stands up, looking angry and hurt and puffy-eyed. “Half of me wants to hit you with something metal.” She sounds serious. “So does the other half. So I’ll go to sleep. You’d better leave in the morning. Switch off the light when you go to bed.”

WHEN I’M WOKEN by the wedge of dim light, my head’s in a fog and my body’s gripped in a tangled sleeping bag. Tiny room, more of a walk-in cupboard; silhouetted girl in a man’s rugby shirt, long, loopy hair … Holly: good. Holly, whom I ordered out of a six-year period of mourning for a missing little brother—presumably dead and skillfully buried—come now to turf me out without breakfast into a very uncertain future … pretty bad. But the little window’s black as night still. My eyes are still gouged with tiredness. My dry, cigarette-and-pinot-blanc-caked mouth croaks, “Is it morning already?”

“No,” says Holly.

THE GIRL’S BREATHING deepens as she drifts off. Her futon’s our raft and sleep is the river. I sift through all the scents. “I’m out of practice,” she told me, in a blur of hair, clothing, and skin. I told her I was out of practice too, and she said, “Bull shit, Poshboy.” A long-dead violinist plays a Bach partita on the clock radio. The crappy speaker buzzes on the upper notes, but I wouldn’t trade this hour for a private concert with Sir Yehudi Menuhin playing his Stradivarius. Neither would I want to travel back to my and the Humberites’ very undergrad discourse on the nature of love at Le Croc the other night, but if I did I’d tell Fitzsimmons et al. that love is fusion in the sun’s core. Love is a blurring of pronouns. Love is subject and object. The difference between its presence and its absence is the difference between life and death. Experimentally, silently, I mouth I love youto Holly, who breathes like the sea. This time I whisper it, at about the violin’s volume: “I love you.” No one hears, no one sees, but the tree falls in the forest just the same.

STILL DARK. THE Alpine hush is miles deep. The skylight over Holly’s bed is covered with snow, but now that the blizzard’s stopped I’m guessing the stars are out. I’d like to buy her a telescope. Could I send her one? From where? My body’s aching and floaty but my mind’s flicking through the last night and day, like a record collector flicking through files of LPs. On the clock radio, a ghostly presenter named Antoine Tanguay is working through Nocturne Hourfrom three till four A.M. Like all the best DJs, Antoine Tanguay says almost nothing. I kiss Holly’s hair, but to my surprise she’s awake: “When did the wind die down?”

“An hour ago. Like someone unplugged it.”

“You’ve been awake a whole hour?”

“My arm’s dead, but I didn’t want to disturb you.”

“Idiot.” She lifts her body to tell me to slide it out.

I loop a long strand of her hair around my thumb and rub it on my lip. “I spoke out of turn last night. About your brother. Sorry.”

“You’re forgiven.” She twangs my boxer shorts’ elastic. “Obviously. Maybe I needed to hear it.”

I kiss her wound-up hair bundle, then uncoil it. “You wouldn’t have any ciggies left, perchance?”

In the velvet dark, I see her smile: A blade of happiness slips between my ribs. “What?”

“Use a word like ‘perchance’ in Gravesend, you’d get crucified on the Ebbsfleet roundabout for being a suspected Conservative voter. No cigarettes left, I’m ’fraid. I went out to buy some yesterday, but found a semiattractive stalker, who’d cleverly made himself homeless forty minutes before a whiteout, so I had to come back without any.”

I trace her cheekbones. “Semiattractive? Cheeky moo.”

She yawns an octave. “Hope we can dig a way out tomorrow.”

“I hope we can’t. I like being snowed in with you.”

“Yeah well, some of us have these job things. Gьnter’s expecting a full house. Flirty-flirty tourists want to party-party-party.”

I bury my head in the crook of her bare shoulder. “No.”

Her hand explores my shoulder blade. “No what?”

“No, you can’t go to Le Croc tomorrow. Sorry. First, because now I’m your man, I forbid it.”

Her sss-sssis a sort of laugh. “Second?”

“Second, if you went, I’d have to gun down every male between twelve and ninety who dared speak to you, plus any lesbians too. That’s seventy-five percent of Le Croc’s clientele. Tomorrow’s headlines would all be BLOODBATH IN THE ALPS and LAMB THE SLAUGHTERER, and as a vegetarian-pacifist type, I know you wouldn’t want any role in a massacre so you’d better shack up”—I kiss her nose, forehead, and temple—“with me all day.”

She presses her ear to my ribs. “Have you heardyour heart? It’s like Keith Moon in there. Seriously. Have I got off with a mutant?”

The blanket’s slipped off her shoulder: I pull it back. We say nothing for a while. Antoine whispers in his radio studio, wherever it is, and plays John Cage’s In a Landscape. It unscrolls, meanderingly. “If time had a pause button,” I tell Holly Sykes, “I’d press it. Right”—I press a spot between her eyebrows and up a bit—“there. Now.”

“But if you did that, the whole universe’d be frozen, even you, so you couldn’t press play to start time again. We’d be stuck forever.”

I kiss her on the mouth and blood’s rushing everywhere.

She murmurs, “You only value something if you know it’ll end.”

NEXT TIME I wake, Holly’s room is gray, like underneath a hole in pack ice. Whispering Antoine is long gone; the radio’s buzzing with French-Algerian rap and the clock says 08:15. She’s showering. Today’s the day I either change my life or I don’t. I locate my clothes, straighten the twisted duvet, and deposit the tissues in a small wicker bin. Then I notice a big round silver pendant, looped over a postcard Blu-Tacked to the wall above the box that serves as a bedside table. The pendant is a labyrinth of grooves and ridges. It’s hand-made, with great care, though it’d be too heavy to wear for long and it’s too big not to attract constant attention. I try to solve it by eye, but get lost once, twice, a third time. Only by holding it in my palm and using my little fingernail to trace a path do I get to the middle. If the maze was real and you were stuck in it, you’d need time and luck. When the moment’s right, I’ll ask Holly about it.

And the postcard? It could be one of a hundred suspension bridges anywhere in the world. Holly’s still in her shower, so I pull the postcard off the wall and turn it over …

Hugo Lamb, meet Sexual Jealousy. Wow. “Ed.” How darehe send Holly a postcard? Or—worse—was it a string of postcards? Was there a follow-up from Athens? Is he a boyfriend? So this is why Normals commit crimes of passion. I want to get Ed’s head fastened into stocks and hurl two-kilo plaster statues of Jesus of Rio at his face until he doesn’t have one. This is what Olly Quinn would want to do to me if he ever found out that I’d poked Ness. Then I notice the 1985 date—deliverance! Hallejulah. But hang on: Why has Holly been carting his postcard around for six years? The cretin doesn’t even know “spinarets” are “minarets.” Unless it’s a private joke. That’d be worse. How darehe share private jokes with Holly? Did Ed give her the maze pendant, too? Makes sense. When she had me inside her, was she imagining I was him? Yes yes yes, I know these snarly thoughts are ridiculous and hypocritical, but they still sting. I want to feed Ed’s postcard to my lighter and watch the Bosphorus Bridge and its sunny day and its sub-sixth-form reportage burn, baby, burn. Then I’d flush its ashes down the sewers, like the Russians did to what was left of Adolf Hitler. No. Deep breath, calm down, keep Hitler out of it, and consider the breezy “Cheers, Ed.” A real boyfriend would write “Love, Ed.” There is the “x,” though. Consider also that if Holly in 1985 was in Gravesend receiving postcards, she wasn’t being gobbled by an Ed on a squeaky European mattress. Ed must’ve been a not-quite-lover-not-quite-friend.