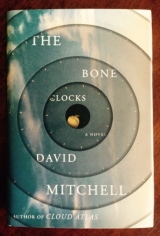

Текст книги "The Bone Clocks"

Автор книги: David Mitchell

Жанры:

Классическое фэнтези

,сообщить о нарушении

Текущая страница: 21 (всего у книги 40 страниц)

Then the “round table” starts and the bollocks gets going.

“Literature should assassinate,” declares the first revolutionary. “ Iwrite with a pen in one hand and a knife in the other!” Grown men stand, cheer, and clap.

The second writer won’t be outdone: “Woody Guthrie, one of the few great American poets, painted the words This Guitar Kills Fascistson his guitar; on mylaptop, I have written This Machine Kills Neocapitalism!” Oh, the crowd goes wild!

A file of latecomers shuffles along the row in front of me. So perfect an opportunity, it might have been scripted. Behind this human shield, I slip out of the room and clip-clop down the whitewashed stairs. Across the open-air courtyard of the Claustro de Santo Domingo, Kenny Bloke is reading to a hemisphere of children. The kids are entranced. Dad had a story about a party where Roald Dahl arrived by helicopter and told everyone he met, “Write books for children, you know—the little shits’ll believe anything.” I exit the ducal gates onto the plaza where Damon MacNish performed last night. Five blocks along the not-quite-straight Calle 36, I light a cigarette, but drop it down a drain before taking a single puff. Cheeseman’s given up smoking, and the tang of tobacco could be a lethal clue. This is serious shit. I’ve never done anything quite like it. On the other hand, no review ever killed a book as wantonly as Richard Cheeseman’s killed Echo Must Die. Plantains sizzle at a stall. A toddler surveys the street from a second-floor veranda, clutching the ironwork, like a prisoner. Soldiers guard a bank with machine guns slung round their necks, but I’m glad my money isn’t dependent on their vigilance; one’s text-messaging while another flirts with a girl Juno’s age. Is Carmen Salvat married? She made no mention.

Focus, Hershey. Serious shit. Focus.

STEP UP FROM the bright hot street into the cool marble-and-teak lobby of the Santa Clara Hotel. Pass the two doormen, who, one suspects, have been trained to kill. They assess clothes, gringocity quotient, credit rating. Remove sunglasses and blink a bit gormlessly– See, boys, I’m a hotel guest—but replace them as you skirt the courtyard, passing preprandial guests sipping cappuccinos and banging out emails where Benedictine nuns once imbibed deep drafts of Holy Spirit. Avoid the eye of the mynah bird and, beyond the sleepless fountain, take the stairs up to the fourth floor. Retrace last night’s midnight steps to the inevitable forking path. A sunny corridor leads around the echoey well of the upper courtyard to my room, where Crispin Hershey bottles out, while the crookeder way twists off to Richard Cheeseman’s Room 405, where Crispin Hershey extracts his due. A minnow of dйjа vu darts by and its name is Geoffrey Chaucer:

“Now, Sirs,” quoth he, “if it be you so lief

To finde Death, turn up this crooked way,

For in that grove I left him, by my fay,

Under a tree, and there he will abide …”

But it’s justice, not death, that Ibe so lief to finde. Any eyewitnesses? None. The crooked way, then. A maid’s trolley is parked outside Room 403, but there’s no sign of the maid. Room 405 is around the corner, the last-but-one down a dead end. Leonard Cohen’s “Dance Me to the End of Love” sashays through my head, and via an arch in the hotel’s outer wall, four floors above street level, Hershey sees roofs, a blue stripe of Caribbean, and dirty cauliflower clouds … Far-off coastal skyscrapers, finished and unfinished. Room 405. Knock-knock. Who’s there? Your come-sodding-uppance, Dickie Cheeseman. Down in the street, a motorbike revs up the octaves. Here’s Cheeseman’s spare swipe-card, retained after my act of Good Samaritanship last night, and here is Fate’s chance to nix my best-laid plan: If Cheeseman noticed he was missing a swipe-card this morning and obtained a replacement with a new code, the little LED on the door will blink red, the door will stay shut, and Hershey must abort mission. But should Fate want me to press ahead, the LED will turn green. There’s a lizard on the door frame. Its tongue flickers.

Swipe the card, then. Go on.

Green. Go go go go go!

The door closes. Good, the room’s been tidied and the bed is made. If a maid arrives, just act like nothing’s wrong. A shirt hangs from a cupboard door and Independent Peopleby Halldуr Laxness lies on the bedside table. In the same way that Muslim women are forbidden to touch the Koran during menstruation, a shit like Richard Cheeseman shouldn’t be allowed to touch Laxness unless he’s wearing a pair of CSI latex gloves. Excellent thought. Unfurl the Marigolds from your jacket pocket and don the same. Good. Find Richard Cheeseman’s suitcase in the wardrobe. New, pricy, capacious: ideal. Open it up and unzip an inner pocket: The zip feels stiff and never-used. Take out the Swiss Army knife and carefully make a half-inch incision in the outer lining. Excellent. Remove the credit-card-sized envelope from your jacket pocket, carefully, and, just as carefully, snip off a corner, and scatter a tiny quantity of the white powder around the suitcase–undetectable to the human eye, but whiffy as skunk shit to a beagle’s nose. Slip the envelope through the incision in the lining of the suitcase. Push it down deep. Rezip the inner pocket. Stow the suitcase back in the wardrobe and check Santa’s left no trail of crumbs. Nothing. All good. Depart the crime scene. Rubber gloves off first, you idiot …

Outside, the maid unbends from behind her cart and gives me a tired smile, and my heart crunches its gears. Even as I say the short word “Hello,” I know I’ve made a fatal slip. She mouths “Hello” back and her mestiza gaze glances off my sunglasses, but I’ve identified myself as an English speaker. Stupid, stupid, stupid. I hurry back down the crooked path. Slowly! Not like a scuttling adulterer. Did the maid see me remove my gloves?

Should I go back and retrieve the cocaine?

Calm down! To the illiterate maid, you’re one more middle-aged white guy with sunglasses. To her, Room 405 was your room. She’s already forgotten seeing you. I pass the heavies in the foyer, and take an alternative route back to Festival Ground Zero. This time I smoke. I deposit the rubber gloves in a bin behind a restaurant, and reenter the gates of the Claustro de Santo Domingo flashing my VIP lanyard. Kenny Bloke is telling a boy, “Now, that’s a brilliant question …” Up via an alternative route, past a large hall of three hundred people listening to Holly Sykes on the far stage reading from her book. I stop. What the sodding hell do all these people see in her? Slack-jawed, focused, gazing devoutly at a translation of the Sykes woman’s text on a big screen above the stage. Even the Festival Elves are neglecting their door duties to tune in to the Angel Authoress. “The boy looked like Jacko,” the Sykes woman reads, “with Jacko’s height, clothes, and appearance, but I knew my brother was in Gravesend, twenty miles away.” Silence fills the hall like snow fills a wood. “The boy waved as if he’d been waiting for me to show up. So I waved back, and then he disappeared into the underpass.” Audience members are actually crying as they listen to this tripe! “How had Jacko traveled that distance, so early on a Sunday morning? He was only seven years old. How had he found me? Why didn’t he wait for me before dashing away into the underpass again? So I began running too …”

I hurry up another flight of steps and sidle back into my seat on the back row, unseen from the stage. People are talking, standing, texting. “But, no, I don’t really agree poets are the unacknowledged legislators of the world,” Richard Cheeseman is ruminating. “Only a third-rate poet like Shelley would believe such wishful thinking.”

Soon the symposium ends and I make my way up to the stage. “Richard, you were the voice of reason, from beginning to end.”

EVENING. ON NARROW streets laid out by Dutchmen and built by their slaves four centuries ago, grandmothers water geraniums. I climb steep stone steps onto the old city wall. Its stones radiate the day’s heat through my thin soles and the rhubarb-pink sun’s fattening nicely as it sinks into the Caribbean. Why doI live in my rainy bitchy anal country again? If Zoл and I go the whole divorce hog, why not up sticks and live somewhere warm? Here would do. Down below, between four lanes of traffic and the sea, boys are playing football on a dirt pitch: One team wears T-shirts, the other goes topless. Up ahead, I find a vacant bench. So. A last-minute stay of execution?

No sodding way. I spent four years on Echo Must Die, and that pube-bearded Cheeseman murdered it in eight hundred words. He elevated his own reputation at the expense of mine. This is called theft. Justice demands that thieves be punished.

I load up my mouth with five Mint Imperials, take out the pay-as-you-go phone Editor Miguel supplied, and, digit by digit, I enter the phone number I copied down from the poster at Heathrow airport. The noise of traffic and seabirds and the footballers fades away. I press Call.

A woman answers straight away: “Heathrow Customs Agency Confidential Line?” I speak in my crappest Sean Connery accent, the Mint Imperials jangling my voice further. “Listen to me. There’s this character, Richard Cheeseman, flying into London from Colombia on BA713, tomorrow night. BA713, tomorrow. You getting all this?”

“BA713, sir. Yes, I’m recording it.” That jolts me. Of course, they’d have to. “And the name was what again?”

“Richard Cheeseman. ‘Cheese’ and ‘man.’ He’s got cocaine in his suitcase. Let a sniffer dog sniff. Watch what happens.”

“I understand,” says the woman. “Sir, may I ask if—”

CALL ENDED, say the chunky pixels on the tiny screen. The sounds of evening return. I spit out the Mint Imperials. They shatter on the stones and lie there, like bits of teeth after a fight. Richard Cheeseman committed the action: I am the reaction. Ethics are Newtonian. Maybe what I just said was sufficient to trigger a bag inspection. Maybe it wasn’t. Maybe he’ll be let off with a private caution, or maybe get his bum spanked in public. Maybe the embarrassment will cause Cheeseman to lose his column in the Telegraph. Maybe it won’t. I’ve done my bit, now it’s up to Fate. I go back down the stone steps, and pretend to tie my shoelace. Surreptitiously I slip the phone into a storm drain. Plop! By the time its remains are disinterred, if indeed they ever are, everybody alive on this glorious evening will have been dead for centuries.

You, dear reader, me, Richard Cheeseman, all of us.

February 21, 2017

APHRA BOOTH BEGINS the next page of her Position Paper, entitled Pale, Male and Stale: The De(CON?)struction of Post-Post-Feminist Straw Dolls in the New Phallic Fiction. I top up my sparkling water, Glug-splush– glig-splosh glugsplshsss sss … To my right, Event Moderator sits with his professorial eyes half shut in a display of worshipful concentration, but I suspect he’s napping. The glass wall behind the audience offers a view down to the Swan River, shimmering silver-blue through Perth, Western Australia. How long has Aphra been droning? This is worse than church. Either our moderator really is asleep, or he’s too scared to interrupt Ms. Booth in mid-position. What am I missing? “When held up to the mirror of gender, masculine metaparadigms of the female psyche refract the whole subtext of an assymetric opacity; or to paraphrase myself, when Venus depicts Mars, she paints from below; from the laundry room and the baby-changing mat. Yet when Mars depicts Venus, he cannot but paint from above; from the imam’s throne, the archbishop’s pulpit or via the pornographer’s lens …” I pandiculate, and Aphra Booth swivels around. “Can’t keep up without a PowerPoint show, Crispin?”

“Just a touch of deep-vein thrombosis, Aphra.” I win a few nervous giggles, and the prospect of a fight injects a little life into the sun-leathered citizens of Perth. “You’ve been going on for hours. And isn’t this panel supposed to be about the soul?”

“This festival does not yitpractice censorship.” She glares at Event Moderator. “Am I correct?”

“Oh, totally,” he blinks, “no censorship in Australia. Definitely.”

“Then perhaps Crispin would pay me the courtesy,” Aphra Booth sweeps her death ray back my way, “of letting me finish. As is clearto anyone out of his intellectual nappies, the soul isa pre-Cartesian avatar. If that’s too taxing a concept, suck a gobstopper and wait quietly in the corner.”

“I’d rather suck on a cyanide tooth,” I mutter.

“Crispin wants a cyanide tooth! Can anyone oblige? Please.”

Oh, how the rehydrated mummies wheezed and tittered!

BY THE TIME Aphra Booth is finished, only fifteen of our ninety minutes remain. Event Moderator tries to lasso the runaway theme and asks me whether I believe in the soul, and if so, what the soul may be. I riff on notions of the soul as a karmic report card; as a spiritual memory stick in search of a corporeal hard drive; and as a placebo we generate to cure our dread of mortality. Aphra Booth suggests that I’ve fudged the question because I’m a classic commitmentphobe—“as we all know.” Clearly this is a reference to my recent, well-publicized divorce from Zoл, so I suggest she stop making cowardly insinuations and say what she wants to say, straight up. She accuses me of Hersheycentricism and paranoia. I accuse her of making accusations she’s too gutless to stand by, emphasizing “gut” with everything I’ve got. Tempers fray. “The tragic paradox of Crispin Hershey,” Aphra Booth tells the venue, “is that while he poses as the scourge of clichй, his whole Johnny Rotten of Literature schtick is the tiredest stereotype in the male zoo. But even thatposturing is lethally undermined by his recent advocacy of a convicted drug smuggler.”

I imagine a hair dryer falling into her bath: Her limbs twitch and her hair smokes as she dies. “Richard Cheeseman is victim of a gross miscarriage of justice, and using his misfortune as a stick to beat mewith is vulgar beyond belief, even for Dr. Aphra Booth.”

“Thirty grams of cocaine was found in the lining of his suitcase.”

“I think,” says Event Moderator, “we should get back to—”

I cut him off: “Thirty grams doesn’t make you a drug lord!”

“No, Crispin; examine the record—I said drug smuggler.”

“There’s no evidence Richard Cheeseman hid the cocaine.”

“Who did, then?”

“ Idon’t know, but—”

“Thank you.”

“—but Richard would never take such a colossal, stupid risk.”

“Unless he was a cokehead who thought his celebrity placed him above Colombian law, as both judge and jury concluded.”

“If Richard Cheeseman were RebeccaCheeseman, you’d be setting your pubic hair on fire outside the Colombian embassy, screaming for justice. The very least that Richard deserves is a transfer to a British jail. Smuggling is a crime against the country of destination, not the country of departure.”

“Oh—so now you’re saying Cheeseman isa drug smuggler?”

“He should be allowed to fight for his innocence from a U.K. prison, and not from a festering pit in Bogotб where there’s no access to soap, let alone a decent defense lawyer.”

“But as a columnist in the right-wing Piccadilly Review, Richard Cheeseman was very hot on prison as a deterrent. In fact, to quote—”

“Enough already, Aphra, you bigoted blob of trans fat.”

Aphra springs to her feet and points her finger at me, like a loaded Magnum. “Apologize now, or you’ll have a crash course in how Australian courts handle slander, defamation, and body fascism!”

“I’m sure all Crispin meant,” says Event Moderator, “was—”

“I de mandan apology from that Weightist Male Pig!”

“Of course I’ll apologize, Aphra. What I meantto call you was a preening, sexist, irrelevant, and bigoted blob of trans fat, who bullies her graduate class into posting five-star reviews of her books on Amazon and who was witnessed, on February the tenth at sixteen hundred hours local time, purchasing a Dan Brown novel from the Relay Bookshop at Singapore Changi International Airport. Some public-spirited witness has already downloaded the clip onto YouTube, you’ll find.”

The audience gasps as one, most gratifyingly.

“And don’t say it was ‘just for research,’ Aphra, because it won’t wash. There. I do hope this apology clarifies matters.”

“You,”Aphra Booth tells Event Moderator, “shouldn’t give a stage to rank, fetid misogynists, and you,” me, “will need a libel lawyer because I am going to sue the living shit out of you!”

Aphra Booth: Exit stage left to sound of thunder.

“Oh, don’t be like that, Aphra,” I call after her. “Your fans are here. Both of them. Aphra … Was it something I said?”

I CYCLE OUT of the strip of souvenir shops and cafйs, but a minute later end up down a dead end at a dusty parade ground. There are Second World War–style huts, and I half recall being told that Italian prisoners of war were interned on Rottnest Island. This train of thought conveys me to Richard Cheeseman, as so many trains of thought do, these days. My fateful act of vengeance in Cartagena last year didn’t so much backfire as explode with horrifying success: Cheeseman is now 342 days into a six-year sentence in the Penitenciarнa Central, Bogotб, for drug trafficking. Trafficking! For one little sodding envelope! The Friends of Richard Cheeseman managed to wangle him a private cell and a bunk, but for this luxury we had to pay two thousand dollars to the gangsters who run his wing. Countless, countless times have I achedto undo my rash little misdeed but, as the Arabic proverb has it, not even God can change the past. We—the Friends—are using every channel we can to shorten the critic’s sentence, or to have him repatriated to the U.K. at least, but it’s an uphill struggle. Dominic Fitzsimmons, the suave and able undersecretary at the Ministry of Justice, knew Cheeseman at Cambridge and is on our side, but he has to act with discretion to avoid charges of cronyism. Elsewhere, sympathy for the lippy columnist is not widespread. People point to the life sentences doled out in Thailand and Indonesia and conclude Cheeseman got off lightly, but there’s nothing “light” about life in the Penitenciarнa. Two or three deaths occur in the prison every month.

I know, I know. One man alone could extract Cheeseman from his Bogotб hellhole and that is Crispin Hershey—but consider the cost. Please. By offering up a full confession, I’d be facing prison myself, quite possibly at Cheeseman’s current address. The legal fees would be ruinous, and no friendsofcrispinhershey.org would procure mea private cell, either—it’d be straight to the piranha tank. Juno and Anaпs would cut me off forever. So a full confession would be tantamount to suicide, and better a guilty coward than a dead Judas.

I can’t do it to myself. I just can’t do it.

Beyond the parade ground the dusty track fizzles out.

We all take a few wrong turns. I turn my bike around.

THE AFTERNOON SUN is a microwave oven, door wide open, cooking all exposed flesh. Rottnest is small as islands go, only eight square miles of naked rock and baked gullies, twists, and bends, ups and downs, and the Indian Ocean is either always visible or always around the next bend. Halfway up a hill I dismount and push. My pulse bangs my eardrums and my shirt’s sticking to my unflat torso. When did I get so sodding unfit? Back in my thirties I could’ve streaked up this slope, but now I’m so knackered I’m nearly puking. When did I last ride a bike? Eight years ago, give or take, with Juno and Anaпs in our back garden at Pembridge Place. One afternoon in the holidays I made an obstacle course for the girls with plank ramps, bamboo-stick slaloms, a tunnel out of a sheet and the washing line, and an evil scarecrow to decapitate with Excalibur as we cycled by. I called it “Scrambler Motocross” and the three of us held time trials. That French au pair, I forget her name, made ruby grapefruit lemonade and even Zoл joined the picnic in the fairy clearing behind the foaming hydrangeas. Juno and Anaпs often asked me to set the course up again, and I always meant to, but there was a review to write, or an email to send, or a scene to polish, and Scrambler Motocross ended up being a one-off. What happened to the kids’ bicycles? Zoл must have disposed of them, I suppose. Disposing of unwanted items proved to be her forte.

Finally, gratefully, I reach the ridge, remount my bike, and coast down the other side. Iron trees untwist from the beige soil around gloopy pools. I imagine the first sailors from Europe landing here, searching for water in this infernal Eden, taking a quiet shit. Yobs from Liverpool, Rotterdam, Le Havre, and Cork; sun-blacked, tattooed, scurvied, calloused, and muscled as all buggery, and—

Suddenly I’m aware that I’m being watched.

It’s strong. It’s uncanny. It’s disturbing.

I scan the hillside. Every rock, bush …

… no. Nobody. It’s just … Just what?

I want to go back to the beginning.

AT THE NEXT turnoff, I follow the road to the lighthouse. No spray-cloaked monarch of the rocks, this; the Rottnest Light is a stumpy middle finger sticking up from a rocky rise, grunting, “Sit on this, mate.”It keeps reappearing at odd angles and in wrong sizes, but refuses to let me arrive. There’s a hill in Through the Looking-Glassthat does the same until Alice stops trying to arrive there—maybe I’ll try the same. What’ll I think about, to distract myself?

Richard Cheeseman, who else? All I wanted was to embarrass Richard Cheeseman. I’d pictured him being held for a few hours at Heathrow airport while lawyers scrambled, and a much-humbled reviewer would be released on bail. That’s all. How could I have predicted that British and Colombian police were enjoying a rare season of cooperation that might result in poor Richard being arrested at Bogotб International Airport, preflight?

“Easily,” my conscience replies. And yes, dear reader, I regret my actions very much, and I’m aiming to atone. With Richard’s sister Maggie, I set up the Friends of Richard Cheeseman to keep his plight in the news—and, lamentable though my misdeed was, I’m hardly in the Premier Division of Infamy. I’m not a certain Catholic bishop who shuffled boy-raping priests from parish to parish to avoid embarrassment for the Holy Church. I’m not ex-president Bashar al-Assad of Syria, who gassed thousands of men, women, and children for the crime of living in a rebel-held suburb. All I did was punish a man who had smeared my reputation. The punishment was a little excessive. Yes, I’m guilty. I regret it. But my guilt is my burden. Mine. My punishment is to live with what I’ve done.

My iPhone trills in my shirt pocket. Needing a breather I pull over into the shade of a shed-sized boulder. I drop the phone and pick it up from the bleached grit by the Moshi Monsters strap that Anaпs attached to it. Appropriately, it’s a text from Zoл or, rather, a photo of Juno’s thirteenth birthday party at the house in Montreal. A house Ipaid for, owned by Zoл since the divorce. Behind a pony-shaped cake, Juno’s holding the riding boots I paid for, and Anaпs’s pulling a goofy face while holding a sign saying, BONJOUR, PAPA! Zoл’s contrived to get herself into the background, obliging me to guess at the photographer’s identity. It could be a member of La Famille Legrange, but Juno’s mentioned some guy called Jerome, a divorced banker with one daughter. Not that I sodding care who Zoл puts it out to, but surely I’ve a right to know who’s tucking my own daughters into bed at night, now their mother has decided it won’t be me. Zoл’s attached no message but the subtext is clear enough: We’re Doing Fine, Thank You Very Much.

I notice a handsome bird on a branch, just a few meters away. It’s white and black with red cap and breast. I’ll photo it and send it to Juno with a funny birthday message. I get out of MESSAGES and press the camera icon, but when I look up I find the bird has flown.

TWO BIKES ARE leaning against the lighthouse when Crispin Hershey finally arrives, which displeases him. I dismount, sticky with sweat, my crotch saddle-sore. I walk out of the nuclear brightness to the shady side of the lighthouse—where, oh, great, two females of the species are finishing a picnic. The younger one’s wearing a faux Hawaiian shirt, knee-length khaki shorts, and daubs of bluish sun-block over her cheekbones, cheeks, and forehead. The older one has earth-mother tie-dyed clothes, a floppy white sun hat, unruly black hair, and sunglasses chosen for maximum coverage. The younger one leaps up—she’s still a teenager—and says, “Wow. Hi. You’re Crispin Hershey.” She speaks in estuary English.

“I am.” It’s been a while since I was recognized out of context.

“Hi. My name’s Aoife, and, uh … Mum here’s actually met you.”

The older woman stands and removes her sunglasses. “Hello, Mr. Hershey. There’s no reason in the world you’d remember, but—”

“Holly Sykes. Yes. We met at Cartagena, last year.”

“ Wow, Mum!” says Aoife. “ TheCrispin Hershey actually knows who you are. Aunt Sharon’s going to be, like, ‘Whaaa?’ ”

She reminds me so much of Juno that I ache, a little.

“Aoife.”There’s a note of maternal reprimand; the megaselling Angel Authoress is uneasy with her fame. “Mr. Hershey deserves some peace and quiet after the festival. Let’s get back to town, hey?”

The young woman swats away a fly. “We only just gothere, Mum. It’ll look rude. You don’t mind sharing a lighthouse, do you?”

“No need to rush off on my account,” I hear myself saying.

“Cool,” says Aoife. “Then have a seat. Or a step. We saw you on the ferry to Rottnest, actually, but Mum said not to disturb you ’cause you looked dead beat.”

Angel Authoress seems keen to avoid me. How rude was I to her at the president’s villa? “Jet lag won’t take ‘please’ for an answer.”

“You’re not wrong.” Aoife fans herself with her cap. “That’s why Australia and New Zealand’re, like, invasion-proof. Any foreign army’d only get halfway up the beach before the time difference’d kick in, and they’d just like whoa, and col lapsein the sand and that’d be it, invasion over. Sorry we missed your event earlier.”

I think of Aphra Booth. “Don’t be. So,” this is to her mother, “you’re appearing at the Writers Festival too?”

Holly Sykes nods, sipping from a bottle of water. “Aoife’s doing a sort of gap year in Sydney, so this trip tied in nicely.”

“My flatmate in Sydney’s from Perth,” adds Aoife, “and she’s always saying, ‘If you go to Perth, you got to go to Rotto.’ ”

Teenagers make me feel so sodding old. “ ‘Rotto’?”

“Here. Rotto is Rottnest Island. Fremantle’s ‘Freo’; ‘afternoon’ is ‘arvo.’ Isn’t it cool how Australians do that?”

No, I’d ordinarily reply, it’s baby talk for grown-ups. But, then, whither humanity sans youth? Whither language sans neologisms? We’d all be Struldbrugs speaking Chaucerian.

“Fancy a fresh apricot?” Aoife offers me a brown paper bag.

MY TONGUE CRUSHES another perfumed fruit against the roof of my mouth. I throw away the apricot stones, thinking of Jack’s mother throwing away the beans that’ll turn into the beanstalk in the morning. “Ripe apricots taste exactly of their color.”

“You talk like a realwriter, Crispin,” says Aoife. “My uncle Brendan’s always teasing Mum, saying now she’s this famous author she ought to talk posher, not all, ‘Watch yer bleedin’ marf or I’ll clock yer one, innit.’ ”

Holly Sykes protests, “I do nottalk like that!”

I miss Juno and Anaпs teasing me. “So what’s this ‘sort of’ gap year of yours about then, Aoife?”

“I’ll be studying archaeology at Manchester from September, but Mum’s Australian editor knows a professor of archaeology at Sydney, so this semester I’m sitting in on the lectures in return for helping with a project at Parramatta. There was a factory there for convict women. It’s been amazing, piecing their lives together.”

“Sounds worthy,” I tell Aoife. “Is your dad an archaeologist?”

“Dad was a journalist, actually. A foreign correspondent.”

“What does he”—too late I spot the “was”—“do now?”

“Unfortunately a missile hit his hotel. In Homs, in Syria.”

I nod. “Excuse my tactlessness. Both of you.”

“It’s eight years ago,” Holly Sykes reassures me, “and …”

“… and I’m lucky,” now Aoife reassures me, “ ’cause there’s, like, a gazillion interviews with Dad on YouTube, so I can go online and there he is, chattering away, large as life. Next best thing to hanging out.”

My dad’s on YouTube too, but I find watching him makes him deader than ever. I ask Aoife, “What was his name, your dad?”

“Ed Brubeck. I’ve got his name, too. Aoife Brubeck.”

“Not theEd Brubeck? Wrote for Spyglassmagazine?”

“That’s him,” says Holly Sykes. “Did you know Ed’s writing?”

“We met! When was it? Washington, about 2002? My former wife’s brother-in-law was on the panel for the Sheehan-Dower Prize. They awarded it to Ed that year, and I’d done a reading in town that day, so we shared a table at dinner that evening.”

Aoife asks, “What did you and Dad talk about?”

“Oh, a hundred things. His job. 9/11. Fear. Politics. The pram in the writer’s hallway. He had a four-year-old back in London, I recall.” Aoife smiles with her whole wide face. “I was working on a journalist character, so Ed let me quiz him. Then we emailed from time to time, after that. When I heard the news, about Syria …” I exhale. “My very belated condolences, to both of you. For whatever they’re worth. He was a bloody good journalist.”

“Thank you,” says one; and “Thanks,” the other.

We gaze out across eleven miles of ferry-plowed sea.

Perth’s dark skyscrapers stand against the light sky.

Twenty paces away, a medium-sized mammal I cannot identify lollops out of the scrub and down the slope. Chubby as a wallaby, reddish-brown, kangaroo forepaws, and a foxy wombat face. A tongue like a finger slurps the apricot stones. “Good God. Whatis that?”

“That charming devil is a quokka,” says Aoife.

“What’s a quokka? Besides a hell of a Scrabble score.”

“An endangered marsupial. The first Dutch who landed here thought they were giant rats, so they called the place Rat’s Nest Island: Rottnest, in Dutch. Most mainland quokkas got killed by dogs and rats, but they’ve managed to survive here.”