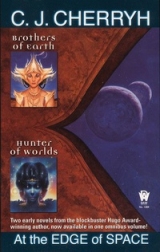

Текст книги "At the Edge of Space (Brothers of Worlds; Hunter of Worlds)"

Автор книги: C. J. Cherryh

Жанр:

Космическая фантастика

сообщить о нарушении

Текущая страница: 9 (всего у книги 36 страниц)

14

Daylight was finally beginning to break through the mists, lightening everything to gray, and there was the first stirring of wind that would disperse the fog.

Kurt skirted the outermost defense wall of Nephane, the rocking, skeletal outlines of ships ghostly in the gray dawn. No one watched this end of the harbor, where the ancient walls curved against Haichema-tleke’s downslope, where the hill finally reached the water, where the walls towered sixty feet or more into the mist.

Here the city ended and the countryside began. A dirt track ran south, rutted with the wheels of hand-pulled carts, mired, thanks to the recent rains. Kurt ran beside the road and left it, heading across country.

He could not think clearly yet where he was bound. Elas was closed to him. If he set eyes on Djan or t’Tefur now he would kill them, with ruin to Elas. He ran, hoping only that it was t’Tefur who would pursue him, out beyond witnesses and law.

It would not bring back Mim. Mim was buried by now, cold in the earth. He could not imagine it, could not accept it, but it was true.

He was weary of tears. He ran, pushing himself to the point of collapse, until that pain was more than the pain for Mim, and exhaustion tumbled him into the wet grass all but senseless.

When he began to think again, his mind was curiously clear. He realized for the first time that he was bleeding from an open wound—had been all night, since the assassin’s blade had passed his ribs. It began to hurt. He found it not deep, but as long as his hand. He had no means to bandage it. The bleeding was not something he would die of. His bruises were more painful: his cord-cut wrists and ankles hurt to bend. He was almost relieved to feel these things, to exchange these miseries for the deep one of Mim’s loss, which had no limit. He put Mim away in his mind, rose up and began to walk again, steps weaving at first, steadier as he chose his direction.

He wanted nothing to do with the villages. He avoided the dirt track that sometimes crossed his way. As the day wore on and the warmth increased he walked more surely, choosing his southerly course by the sun.

Sometimes he crossed cultivated fields, where the crops were only now sprouting, and the earliest trees were in bloom and not yet fruited. Root-crops like staswere stored away in the safety of barns, not to be had in the fields.

By twilight he was feeling faint with hunger, for he had not eaten—he reckoned back to breakfast a day ago. He did not know the land, dared not try the wild plants. He knew then that he must think of stealing or starve to death, and he was sorry for that, because the country folk were generally both decent and poor.

The bitter thought occurred to him that among the innocent of this world his presence had brought nothing but grief. It was only his enemies that he could never harm.

Mim stayed with him. He could not so much as look at the stars overhead without hearing the names she gave them: Ysime the pole star, mother of the north wind; blue Lineth, the star that heralded the spring, sister of Phan. His grief had settled into a quieter misery, one with everything.

In the dark, there came to his nostrils the scent of wood-smoke, borne on the northwest wind.

He turned toward it, smelled other things as he drew nearer, animal scents and the delicious aroma of cooking. He crept silently, carefully toward the fold of hills that concealed the place.

There was no house, but a campfire tended by two men and a youth, country folk, keepers of flocks, cachiren.He heard the soft calling of their wool-bearing animals from somewhere beyond a brush barricade on the other side of the fire.

A snarled warning cut the night. The shaggy tilofthat guarded the cachinlifted its head, his hackles rising, alerting the cachiren,they who scrambled up, weapons in hand, and the beast raced for the intruder.

Kurt fled, seeking a pile of rock that had tumbled from the hillside, and tried to find a place of refuge. The beast’s teeth seized his ankle, tore as he jerked free and scrambled higher.

“Come down!” shouted the youth, spear poised for throwing. “Come down from there.”

“Hold the creature off,” Kurt shouted back. “I will gladly come down if you will only call him off.”

Two of them kept spears aimed at him, while the youth went higher and dragged the snarling and spitting guard-beast down again by his shaggy ruff.

Kurt clambered down gingerly and spoke to them gently and courteously, for they prodded him with their spears, forcing him in the direction of the firelight, and he feared what they would do when they saw his human face.

When he reached the light he kept his head down, and knelt by the fireside and sat back on his heels in an at-home posture. The keen point of a spearblade touched beneath his shoulder. The other two men circled to the front to look him over.

“Human,” one exclaimed, and point the point pressed deeper and made him wince.

“Where are the rest of you?” the white-haired elder asked.

“I am not Tamurlin,” said Kurt, “and I am alone. I beg you, I need food. I am of the Methi’s people.”

“He is lying,” said the boy behind him.

“He might be,” said the elder, “but he talks manlike.”

“You do not need to give me hospitality,” said Kurt, for the sharing of bread and fire created a religious bond forever unless otherwise agreed upon from the beginning. “But I do ask you for food and drink. It is the second day since I have eaten.”

“Where did you come from?” asked the elder.

“From Nephane.”

“He is lying,” the boy insisted. “The Methi killed the others.”

“Unless one escaped.”

“Or more than one,” said the elder.

“May the light of Phan fall gently on thee,” Kurt said, the common blessing. “I swear I have not lied to you, and I am no enemy.”

“It is, at least, no Tamurlin,” said the second man. “Are you house-friend to the Methi, stranger?”

“To Elas,” said Kurt.

“To Elas,” echoed the elder in amazement. “To the sons of storm,—a human for a house-friend? This is hard to believe. The Indras-descended are too proud for that.”

“If you honor the name of Elas,” said Kurt, “or of Osanef, which is our friend,—give me something to eat. I am about to faint from hunger.”

The elder considered again and finally extended an arm in invitation to the meal they had left cooking beside their fire. “Not in hospitality, stranger, since we do not know you, but there is food and drink. We are poor men. Take sparingly, but be free of it, if you are as hungry as you say. May the light of Phan fall upon thee in blessing or in curse according to what you deserve.”

Kurt moved carefully, for the spear was surely still at his back. He knelt down by the rock where the food was warming and took one of the three meal cakes, breaking off half; and a little crumb of the soft cheese that lay on a greasy leather wrap beside them. But he used the fine manners of Elas, not daring to do otherwise with their critical eyes on him and the spear ready.

When he was done he rose up and bowed his thanks. “I will go my way now,” he said.

“No, stranger,” said the second man. “I think you ought to stay with us and go to our village in the morning. In this district we see few travelers from Nephane, and I think you would be safer with us. Someone might take you for Tamurlin and put a spear through you before he realized his mistake. That would be sad for both of you.”

“I have business elsewhere,” said Kurt, playing out the farce with the rules they set and bowing politely. “And I thank you for your concern, but I will go on now.”

The elder man brought his spear crosswise in both hands. “I think my son is right. You have run from somewhere, that much is certain, and I am not sure that you are house-friend to Elas. No, it is more likely the Methi simply missed killing you with the others, and we well know in the country what humans are.”

“If I do come from Djan-methi, you will not win her thanks by delaying me on my mission.”

“What, does the Methi send out her servants without provisions?”

“I had an accident,” he said. “My mission is urgent; I had no time to go back. I counted on the hospitality of the country folk to help me on my way.”

“Stranger, you are not only a liar, you are a bad liar. We will take you to our village and see what the Afen has to say about you.”

Kurt ran, plunged in a wild vault over the brush barricade and in among the startled cachin,creating panic as their woolly bodies scattered and herded first to the rocks and then back toward the barricade, breaking it down in their mad rush to escape. The tilof’s sharp cries resounded in the rocks. The beast and the men had work enough at the moment.

Kurt climbed, fingers and sandaled toes seeking purchase in the crevices of the rocks, sending stones cascading down the hillside. He cleared the crest, found a level, brushy ground and ran, desperate, trusting pursuit would be at least delayed.

But word would go back to Nephane and to Djan, and she would be sure now the way he had fled. Ships could outrace him down the coast.

If he did not reach his own abandoned ship and secure the means to live, he was finished in this land. Djan would have guessed it already, and now she could lay her ambush with assurance.

If she knew the precise location of his ship, he could not hope to avoid it.

The sun rose over the same grassy rangeland that had surrounded him for the last several days, dry grass and wind and dust.

Kurt leaned on his staff, a twisted branch from which he had stripped the twigs, and looked toward the south. There was not a sign of the ship. Nothing. Another day of walking, of the tormenting heat and the infection’s throbbing fever in his wound. He started moving again, relying on the staff, every step a jarring and constant pain, his mouth so dry that swallowing hurt.

Sometimes he rested, and thought of lying down and ceasing to struggle against the thirst; sometimes he would do that, but eventually misery and the habit of life would bring him to his feet and set him walking.

Phan was a terrible presence in these lands, wrathfully blinding in the day, deserting the land at night to a biting cold. Kurt rubbed blistered skin from his nose, his hands. His bare legs and especially his knees were swollen with sunburn, tiny blisters which many times formed and burst, making a crack-line that oozed and bled.

The thirst was beyond bearing as the sun reached its zenith. There was no water, had been none since the small stream the day before—or the day before that. Time blurred since he had entered this land. He began to wonder if he had already missed the ship, bypassing it over one of the gently rolling hills. That would be irony: to live by the skills of pinpointing a ship from one star to another and to die by missing a point over a hill.

He turned west finally, toward the sea, thinking that he could not fail at least to find that, hoping that the lower country would have fresh water. The changing of the seasons had confused him. He remembered green around the ship, green in winter. Had it been so far south? The sailing—he could not remember how many days it had taken.

By afternoon he ceased to care what direction he was moving in and knew that he was killing himself, and did not care. He started down a hillside, too tired to take the safer slope, and slipped on the dusty grass. He slid, opening the lacerations on his hands and knees, grass and stone stripping sunburned skin and blisters from his exposed flesh as he rolled down the slope.

The pain grew less finally, or he adjusted to it, he knew not which. He found himself walking and did not remember getting to his feet. It was not important any more, the ship, the sea, life or death. He moved and so lived, and therefore moved.

The sun dipped horizonward into dusk, a beacon that lit the sky with red, and Kurt locked onto it, a reference point, a guidance star in this void of grass. It led him downcountry, where there were trees and the land looked more familiar.

Night fell, and he stood on the broad shoulder of a hill, leaning on his staff, fearing if he sat down now he would not have the strength in his burn-swollen legs to get up again. He started the long descent toward the dark of the woods.

A light gleamed off across the wide valley, a light like a campfire. Kurt paused, rubbed his eyes to be sure it was there. It was a pinpoint like a very faint star, that flickered, but stayed discernible in all that distance and desolation.

He headed for it, driven now by feverish hope, nerved to kill if need be to obtain food and water.

It gleamed nearer, just when he feared he had lost it in his descent. He saw it through the brush. Men’s voices—nemet voices—were audible, soft, quiet in conversation.

Then silence. Brush moved. The fire continued to gleam. He hesitated, feeling momentary panic, a sense of being stalked in turn.

Brush crashed near him and strong arm took him from behind about the throat, bent him back. He fell, pulled down by two mean, weighted with a knee on his right arm, another hand pinning his left. A knife whispered from its sheath and rested across his throat.

The man on his left checked the other hand on his wrist. Kurt ceased to struggle, trying only to breathe.

“It is t’Morgan,” said a whisper. Gentle hands searched his belt for weapons, found nothing, tugged his arms free of those who held him and drew him up, those who had been lately threatening him handling him carefully, lifting him to his feet, aiding him to stand.

“Are you alone?” one asked of him.

“Yes,” Kurt tried to say. They almost had to carry him, bringing him into the circle of firelight. Other nemet joined them from the shadows.

Kta was among them. Kurt saw his face among the others and felt his sanity had left him. He tried to go toward him, shaking free of the others.

He fell. When he managed to get his arms beneath him and tried again to sit up, Kta was beside him. The nemet washed his burning face from a waterskin, offered it to his lips and took it away before he could make himself sick with it.

“How did you come here?” Kurt found his own voice unrecognizable.

“Looking for you,” said Kta. “I thought you might understand a beacon fire, which drew me once to you. And you did see it, thank the gods. I planned to reach your ship and wait for you there, but I have not been able to find it. But gods, no one walks cross-country. You are mad.”

“It was a hard walk,” Kurt agreed. Kta smoothed his filthy hair aside, woman-tender, his fingers careful of burned skin, pouring water to cool his face.

“Your skin,” said Kta, “is cooked. Merciful spirits of heaven, look at you.”

Kurt rubbed at the stubble that protected his lower face, aware how bestial he must be in the eyes of the nemet, for the nemet had very little facial hair, very little elsewhere. He struggled to sit, and bending his legs made it feel like the sunburned skin of his knees would split. “Food,” he pleaded, and someone gave him a bit of cheese. He could not eat much of it, but he washed it down with a welcome swallow of telisefrom Kta’s flask.

Then it was as if the strength that was left poured out of him. He lay down again and the nemet made him as comfortable as they could with their cloaks, washed the ugly wound across his ribs with water and then—which made him cry aloud—with fiery telise.

“Forgive me, forgive me,” Kta murmured through the haze of his delirium. “My poor friend, it is done, it will mend.”

He slept then, conscious of nothing.

The camp began to stir again toward dawn, and Kurt wakened as one of the men added wood to the fire. Kta was already sitting up, watching him anxiously.

Kurt groaned and sat up, dragging himself to a cross-legged posture despite his knees. “A drink, please, Kta.”

Kta nodded to the boy Pan, who hastened to bring Kurt a waterskin and stas,which had been baked last night. It was cold, but with salt it went very well, washed down with telise.He ate it to the last, but dared not force the second one offered on his shrunken stomach.

“Are you feeling better?” asked Kta.

“I am all right,” he said. “You should not have come after me.”

And then a second, terrible thought hit him: “Or did Djan send you to bring me back?”

Kta’s face went thin-lipped, a killing anger that turned Kurt cold. “No,” he said. “I am outlawed. The Methi has killed my father and mother.”

“No.” Kurt shook his head furiously, as if that could unsay the truth of it. “Oh, no, Kta.” But it was true. The nemet’s face was calm and terrible. “ Icaused it,” Kurt said. “ Icaused it.”

“She killed them,” said Kta, “as she killed Mim. We know Mim’s tale from Djan-methi’s own lips, spoken to my father. My people will not live without honor, and so my parents died. My father confronted the Methi in the Upei for Mim’s death and for the Methi’s other crimes—and she cast him from the Upei, which was her right. My father and my mother chose death, which was their right. And Hef with them. He would not let them go unattended into the shadows.”

“Aimu?” Kurt asked, dreading to know.

“I gave her to Bel as his wife. What else could I do, what other hope for her? Elas is no more in Nephane. Its fire is extinguished. I am in exile. I will not serve the Methi any longer, but I live to honor my father and my mother and Hef and Mim. They are my charges now. I am all that is left, now that Aimu can no longer invoke the Guardians of Elas.”

Kta’s lips trembled. Kurt ached for him no less than for his family, for it was unbecoming for a man of the Indras to shed tears. It would shame him terribly to break.

“If,” said Kurt, “you want to discharge your debt to me you have discharged it. I can live in this green land if you only give me weapons and food and water. Kta, I would not blame you if you never wanted to look at me again; I would not blame you if you killed me.”

“I came for you,” said Kta. “You are also of Elas, though you cannot continue our rites or perpetuate our blood. When the Methi struck at you, she struck at us. We are of one house, you and I. Until one or the other of us is dead, we are left hand and right. You have no leave to go your way. I do not give it.”

He spoke as lord of Elas, which was his right now. The bond Mim had forged reasserted itself. Kurt bowed his head in respect.

“Where shall we go now?” Kurt asked. “And what shall we do?”

“We go north,” said Kta. “Light of heaven, I knew at once where you must go, and I am sure the Methi does; but it would have been more convenient if you had brought your ship to earth in the far north. The Ome Sin is a closed bottle in which the Methi’s ships can hunt us at their pleasure. If we cannot escape its neck and reach the northern seas, you and I are done, my friend, and all these brave friends who have come with me.”

“Is Bel here?” Kurt asked, for about him he saw many familiar faces, but he feared greatly for t’Osanef and Aimu if they had elected to stay in Nephane. T’Tefur might carry revenge even to them.

“No,” said Kta. “Bel is Sufaki, and his father needs him desperately just now. For all of us that have come, there is no way back, not as long as Djan rules. But she has no heir, and being human—there is no dynasty. We are prepared to wait.”

Kurt hoped silently that he had not given her one. That would be the ultimate bitterness, to ruin these good men by that, when he had brought them all to this pass.

“Break camp,” said Kta. “We start—”

Something hissed and struck against flesh, and all the camp exploded into chaos.

“Kta!” a man cried warning, and went down with a feathered shaft in his throat. About them in the dawn-dim clearing poured a horde of howling creatures that Kurt knew for his own kind. One of the nemet pitched to the ground almost at his feet with his face a bloody smear, and in the next moment a crushing blow across the back brought Kurt down across him.

Rough hands jerked him up, and his shock-dazed eyes looked at a bearded human face. The man seemed no less surprised, stayed the blow of his ax, then bellowed an order to his men.

The killing stopped, the noise faded.

The human put out his bloody hand and touched Kurt’s face, his hair-shrouded eyes dull and mused with confusion. “What band?” he asked.

“I came by ship,” Kurt answered him. “By starship.”

The Tamurlin’s blue eyes clouded, and with a snarl he took the front of Kurt’s nemet garb and ripped it off his shoulder, as though the nemet dress gave the lie to his claim. But then there was a cry of awe from the humans gathered around. One took his sun-browned arm and held it up against Kurt’s pale shoulder and turned to his comrades, seeking their opinion.

“A man from shelters,” he cried, “a ship-dweller.”

“He came in the ship,” another shouted, “in the ship, the ship.”

They all shouted the ship, the ship, over and over again, and danced around and flashed their weapons. Kurt looked around at the carnage they had made in the clearing, his heart pounding with dread at seeing one and another man he knew lying there. He prayed Kta had escaped: some had dived for the brush.

He had not. Kta lay on his face by the fire, unconscious—his breathing was visible.

“Kill the others,” said the leader of the Tamurlin. “We keep the human.”

“ No!” Kurt cried, and jerked ineffectually to free his arms. His mind snatched at the first argument he could find. “One of them is a nemet lord. He can bring you something of value.”

“Point him out.”

“There,” Kurt said, jerking his head to show him. “Nearest the fire.”

“Let’s take all the live ones,” said another of the Tamurlin, with a look in his eyes that boded no good for the nemet. “Let’s deal with them tonight at the camp—”

“ Ya!” howled the others, agreeing, and the chief snarled a reluctant order, for it had not been his idea. He took command of the situation with a sweep of his arm. “Pick them all up, all the live ones, and bring them. We’ll see if this man really is from the ship. If he isn’t, we’ll find out what he really is.”

The others shouted agreement and turned their attention to the fallen nemet, Kta first. Him they shook and slapped until he began to fight them again, and then they twisted his hands behind him and tied him.

Two other nemet they found not seriously hurt and treated in similar fashion. A third man they made walk a few paces, but he could not do so, for his leg was pierced with a shaft. One of them kicked his good leg from under him and smashed his skull with an ax.

Kurt twisted away, chanced to look on Kta’s face, and the look in the nemet’s eyes was terrible. Two more of his men they killed in the same way, and at each fall of the ax Kta winced, but his gaze remained fixed. By his look they could as well have killed him.