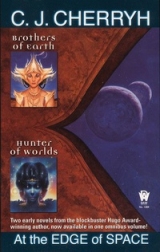

Текст книги "At the Edge of Space (Brothers of Worlds; Hunter of Worlds)"

Автор книги: C. J. Cherryh

Жанр:

Космическая фантастика

сообщить о нарушении

Текущая страница: 26 (всего у книги 36 страниц)

There had been smoke on the horizon two days ago. All the sentries had reported it, and the children had thronged the big dome rock in the throat of the pass to see it. But then her father had chased them all back into the yard and told them that the strangers would get them if they did not stay where they belonged. So Arle reasoned that it was like the dog, something for them to be afraid of while the grownups understood what it really was and knew how to deal with it. They would take care of matters, and the crops would go in come fall, and be harvested next spring, and life would go on quite normally.

She curled up again in her bed and pulled the sheet up to her chin. It made it feel like bed, and protection. Soon she shut her eyes and drifted back to sleep.

Something boomed, shook the very floor and the bottles on the dresser and lit the branches in red relief on the wall. Arle scrambled for the view at the window, too sleepy and too stunned to have cried out at that overwhelming noise. Men were running everywhere. The gate was down with fire beyond and dark shapes against it, and people ran up and down the hall outside her room. Her oldest brother came bursting in with a flashlight, exclaimed that she should get out of the window and seized her by the wrist, not even waiting for her to get her feet under her. He pulled her with him at a run, taking her, she knew, to the cellar, where the children had always been told to go in an emergency. She began to cry as they hit the outside stairs, for she did not want to go down into that dark place and wait.

Suddenly light broke about them, awful heat and noise, stone chips and powder showering down upon them. Arle sprawled, hurting her hands and ribs and knees upon the steps, crawling back from the source of that light even before her mind had awakened to the fact that something had exploded. Then she saw her brother’s face, odd-tilted on the steps, his eyes with the glazed look of a dead animal’s. His hand when she took it was loose. Light flashed. Stone showered down again, choking her with dust.

What she did then she only remembered later—tumbling off the side of the steps, landing in the soft earth of the flowerbed, running, lost among the dark shapes that hurtled this way and that.

She found herself crouching in the rubble at the gate, while dark bodies moved against the light a little beyond her. The yard was like that cellar, a horrible dead-end place where one could be trapped. She broke and ran away from the house, trying to go down the pass a little way to that forbidden path up the cliffs, to hide and wait above until she could come back and find her family.

It was dark among the rocks for a moment, the light of the fire cut off by the bending of the road; and then as she rounded the bend toward the narrowing of the cliffs a dark man-shape stood by the dome rock in the very narrowest part of the pass, outlined against the moon and the downslope of the road toward the valley fields. Arle saw him too late, tried to scramble aside into the rocks, but the man seized her, drew her against him with his arm, and silenced her with a hand that covered her mouth and nose and threatened to break her neck as well.

He released her when her struggles grew weak, seized the collar of her thin gown, and raised his other hand to hit her, but she whimpered and flinched down as small as she could. Instead he raised her back by both arms and shook her until her head snapped back. His shadowed face stared into hers in the moonlight. She stood still and suffered him to cup her small face between his rough hands, to smooth her tangled hair, to use his thumbs to wipe the tears from her cheeks.

“Help us,” she said then, thinking this was one of the neighbor men come to aid them. “Please come and help us.”

His hands on her shoulders hurt her. He stood there for a moment, while she trembled on the verge of tears, and then he gripped her arm in one cruel hand and began to walk down the road away from the house, dragging her with him, making her legs keep his long strides.

She stumbled on the rocks as they descended from the road to the orchard and turned her ankle in the soft ground among the apple and peach trees; and there were thorns and cutting stubble on the slopes of the irrigation ditch. He strode across the water, hauling her up the other side by one arm as a careless child might handle a doll, and waited only an instant to let her gain her feet before he walked on, dragging her at a near run, until at last she did stumble and fell to her knees sobbing.

Then he drew her aside, into the shadow of the trees, set her against the low limb of an aged apple tree, and looked at her, still holding her by a firm grip on her arm. “Where were you going?” he asked her.

She did not want to tell him. The scant light there was filtering through the apple leaves showed the outline of boots, loose trousers, leather harness, clothing such as no farmer wore, and his lean, hard face was strange to her. But he shook her and repeated the question, and her lips trembled and clear sense left her.

“I was going to hide and come back.”

“Is there any help you can get to?”

She jerked her head in the direction of the Berney farm, where Rachel Berney lived, and her brother Johann and the Sullivans, who had a daughter her age.

“You mean that house five kilometers west of here?” he asked. “Forget it. Is there anywhere else?”

“I don’t know,” she said. “I—could hide in the rocks.”

He took her hand again, a dry, strong grip that frightened her, for he could crush the bones if he closed down harder. “And where would you go after? There’s not going to be anything left back there.”

“I want to go home.”

“You can’t. Think. Think of some place safe I could leave you.”

“I don’t know any.”

“If I left you right here, could you walk down from the heights to the river? Could you walk that far?”

She looked at him in dismay. The river was visible from the heights, far, far down in the valley. When they went, it meant taking the truck and going a long distance down the road. She could not imagine how long it would take to walk it, and it was hot in the daytime—and there were men like him on the roads. She began to cry, not alone for that, for everything, and she cried so hard she was about to be sick. But he shook her roughly and slapped her face. The hurt was already so much inside that she hardly knew the pain, except that she was afraid of them and she was going to be sick at her stomach. Out of fear she swallowed down the tears and the sickness with them.

“You have to think of somewhere I can put you. Stop that sniffing and think.”

“I want to go home,” she cried, at which he looked at her strangely and his grip lessened on her arm. He smoothed her hair and touched her face.

“I know you do. I know. You can’t.”

“Let me go.”

“They’re dead back there, can’t you understand that? If they catch either one of us now they’ll skin us alive. I have to get rid of you.”

“I don’t know what to do. I don’t know. I don’t know.”

Then she thought he would hit her. She screamed and flinched back. But instead he put his arms about her, picked her up, hugged her head down into his shoulder, rocking her in his arms as if she had been an infant. “All right,” he said. “I’ll see what I can do.”

Aiela took the corridor to the paredre,his mind boiling with frustration and smothered kalliran and human obscenities, and raged at Isande’s gentle presence in his thoughts until she let him alone. For fifteen precious days he had monitored Daniel’s every movement. The human language began to come more readily than the kalliran: human filth and human images poured constantly through his senses, blurring his own perception of what passed about him, cannibalizing his own life, his own separate thoughts.

Now, confronted by an iduve at the door of the paredre,he could scarcely gather enough fluency to explain his presence in any civilized language. The iduve looked at him sharply, for his behavior showed a mental disorder that was suspect, but Chimele had given standing orders and the man relented.

“Aiela?” Chimele arose from her desk across the room, her brows lifted in the iduve approximation of alarm. Aiela bowed very low. Courtesy demanded it, considering the news he bore.

“Daniel has encountered a difficulty,” he said.

“Be precise.” Chimele took a chair with a mate opposite and gestured him to sit.

“The Upweiss raid,” Aiela began hoarsely: Chimele insisted upon the chronological essentials of a thing. He forced his mind into order, screened against the random impulses that fed from Daniel’s mind and the anxious sympathy from Isande’s. “It went as scheduled. Anderson’s unit hit the Mar estate. Daniel hung back—”

“He was not to do so,” Chimele said.

“I warned him; I warned him strongly. He knows Anderson’s suspicions of him. But Daniel can’t do the things these men do. His conscience—his honor,” he amended, trying to choose words that had clear meaning for Chimele—“is offended over the killings. He had to kill a man in the last raid.”

Chimele made a dismissing move of her hand. “He was attacked.”

“I could explain the human ethical—”

“Explain what is at hand.”

“There was a child—a girl. It was a crisis. I tried to reason with him. He shut me out and took her away. He is still going, deserting Anderson—and us.”

There were no curses in the iduve language. Possibly that contributed to their fierceness. Chimele said nothing.

“I’m trying to reason with him,” Aiela said. “He’s exhausted—drained. He hasn’t slept in twenty hours. He lay awake last night, sick over the prospect of this raid. He’s going on little sleep, no water, no food. He can’t expect to find water as he’s heading, not until the river. They can’t make it.”

“This is not a rational human response.” That was a question. Chimele’s voice had an utter calm, not a good sign in an iduve.

“It is a human response, but it is not rational.”

Chimele hissed and rose, hands on her hips. “Is it not your duty to anticipate such responses and deal with them?”

“I don’t blame him,” he said. Then, from his heart: “I’m only afraid I might have done otherwise.” And that thought so depressed him he felt tears rise. Chimele looked down on him in incredulity.

“ Au,by what am I served? Explain. I am patient. Is this a predictable response?”

Aiela could have screamed aloud. The paredrefaded. He shivered in the cold of a Priamid night, the glory of spiraling ribbons of stars overhead, the fragile sweet warmth of another being in his arms. Tears filled his eyes; his breath caught.

“Aiela,” Chimele said. The iduve could not cry; they lacked the reflex. The remembrance of that made him ashamed in her sight.

“The reaction,” he said, “is probably instinct. I—have grown so much into him I—cannot tell. I cannot judge what he does any longer. It seems right to me.”

“Is it dhis-instinct, a response to this child?”

“Something like that,” he said, grateful for her attempt at equation. Chimele considered that for a moment, her eyes more perplexed now than angry.

“It is difficult to rely on such unknown quantities. I offer my regret for what you must be feeling, though I am not sure I can comprehend it. Other humans—like Anderson—are immune to this emotion where the young are concerned. Why does Daniel succumb?”

“I don’t live inside Anderson. I don’t know what goes on in his twisted mind. I only know Daniel—this night—could not have done otherwise.”

“Kindly explain to Daniel that we have approximately three days left, his time. That Priamos itself has scarcely that long to live, and that he and the child will be among a million beings perishing if we have to resort to massive attack on this world.”

“I’ve tried. He knows these things, intellectually, but he shuts me out. He refuses to think of that.”

“Then we have wasted fifteen valuable days.”

“Is that all?”

There was hysteria in his voice; and it elicited from Chimele a curious look, the embarrassment of an observer who had no impulse to what he felt.

“You are exhausted,” she judged “You can be sedated for the rest of the world’s night. You can do nothing more with this person and I know how long you have worked without true rest.”

“No.” He assumed a taut control of his voice and slowed his breathing. “I know Daniel. Good sense will come back to him after he has run awhile. That area is swarming with trouble in all forms. He will need me.”

“I honor your persistence. Stay in the paredre.If you are going to attempt to advise him I should prefer to know how you are faring. If you change your mind about the sedation, tell me; if we are to lose Daniel, your own knowledge of humans becomes twice valuable. I do not want to risk your health. I leave matters in your hands; rest, if you can.”

“Thank you.” He drew himself to his feet, bowed, and moved away.

“Aiela.”

He looked back.

“When you have found an explanation for his behavior, give it to me. I shall be interested.”

He bowed once more, struggling between loathing and love for the iduve, and decided for the moment on love. She did try. She tried with her mind where her heart was inadequate, but she wanted to know.

In the shadows of the paredrea comfortable bowl chair, such as the iduve chose when they would relax, provided a retreat. He curled into its deep embrace and leaned his head back upon the edge, slipping again into the mental rhythms of Daniel’s body, becoming human, feeling again what he felt.

In the small corner of his mind still himself, Aiela knew the answer. It had been likely from Daniel’s first step onto the surface of Priamos.

Years and a world ago, when Aiela was a boy, the staff had brought into the lodge one of the hunting birds that nested in the cliffs of the mountains, wing-broken. He had nursed it, he had been proud of it, thought it his. But the first time it felt the winds of Ryi under its wings, it was gone.

7

Aiela was back. Daniel clamped down a silence against him, shifted the child’s slight weight in his arms, and felt her arms tighten reflexively about his neck. Above them a star burned, a blaze of white brighter than any star that had ever shown in Priamid skies. When people saw it they thought amautand shuddered at the presence, aware it was large, but yet having no concept what it was. They might never know. If it swung into tighter orbit it would be the final spectacle in Priamos’ skies, that had of late seen so many comings and goings, the baleful red of amaut ships, the winking white of human craft deploying troops, mercenaries serving the amaut. When Ashanomecame it would be one last great sunset over the world at once, the last option of the iduve in a petty quarrel that threatened the existence of his species, that counted one man or one minor civilization nothing against the games that occupied them.

You know better,Aiela sent him. Simultaneous with the words came rage, concern for them, fear of Chimele. Daniel seized wrathfully upon the latter, which Aiela vehemently denied.

Daniel. Think. You don’t know where you’re going or what you’re going to do with that girl.All right. Defeat. Aiela recognized the loathing Daniel felt for what they had asked him to do. Human as he was, he had been able to cross the face of Priamos unremarked, one of the countless mercenaries that looted and killed in small bands at the amaut’s bidding. He was a rough man, was Daniel: he could use that heavy-barreled primitive gun that hung from his belt. His slender frame could endure the marches, the tent-camps, the appallingly primitive conditions under which the human force operated. But he had no heart for this. He had been rackingly sick after the only killing he had done, and Anderson, the mercenary captain, had put him on the notice he would be made an example if he failed in any order. This threat was nothing. If Daniel could ignore the orders of Chimele of Ashanome,nothing the brutish Anderson could invent was enough; but Anderson fortunately had not realized that.

I can’t help you,Aiela said. That child cried for home, and you lost all your senses, every other bond. Now I suppose I’m the enemy.

No,Daniel thought, irritated by Aiela’s analysis. You aren’t.And: I wish you were—for it was his humanity that was pained.

Listen to me, Daniel. Accept my advice and let me guide you out of this incredible situation.

The word choice might have been Chimele’s. Daniel recognized it. “Kill the girl.” Why don’t you just come out with the idea. “Kill her, one life for the many.” Say it, Aiela. Isn’t that what Chimele wants of me?He hugged the sleeping child so tightly it wakened her, and she cried out in memory and fought.

“Hush,” he told her. “Do you want to walk awhile?”

“I’ll try,” she said, and he chose a smooth place on the dirt road to set her down, she tugging in nervous modesty at the hem of her tattered gown. Her feet were cut with stubble and bruised with stones. She limped so it hurt to watch her, and held out her hands to balance on the edges of her feet. He swore and reached out to take her up again, but she resisted and looked at him, her elfin face pale in the moonlight.

“No, I can walk. It’s just sore at first.”

“We’re going to cut west when we reach the other road. Maybe we’ll find a refugee family—there’s got to be somebody left.”

“Are you going to leave those men and not go back?”

The question disturbed him. Aiela pressed him with an echo of the same, and Daniel screened. “They’ll have my hide if they find me now. Maybe I’ll head northwest and pick up with some other band.” That for Aiela. A night’s delay, a day at the most. I can manage it. I’ll think of something.“Or maybe I’ll go west too. I’ll see you safe before I do anything.”

A man alone can’t make it across that country,Aiela insisted. Get rid of her, let her go. No! listen, don’t shut me out. I’ll help you. Your terms. Give me information and I’ll take your part with Chimele.

Daniel swore at him and closed down. Even suggesting harm to the girl tore at Aiela’s heart; but he was afraid. His people had had awe of the iduve fed into them with their mothers’ milk, and he was not human; Daniel knew the kallia so well, and yet there were still dark corners, reactions he could not predict, things that had to do with being kallia and being human. Aiela’s people had no capacity to fight: it was not in the kalliran nature to produce a tyranny, not in a culture where there was no supreme executive, but a hierarchy of councils. One kallia simply lacked the feeling of adequacy to be either tyrant or rebel. Giyrewas supposed to be mutual, and he had no idea how to react when trust was betrayed. Kallia were easy prey for the iduve: they always yielded to greater authority. In the kalliran mind it just did not occur that it could be morally wrong, or that the Order in which they believed did not exist off Aus Qao.

Daniel.The quiet touch was back in his mind, offended, as angry as Daniel had ever felt him. The things you do not know about kallia are considerable. You lack any sense aboutgiyre yourself, so I suppose it does not occur to you that I have it for all beings with whom I deal—even for you. I am not human. I do not lie to my friends, destroy what is useless, or break what is whole. I can also accept defeat when I meet it. Abandon the child there. I will get her to safety, I will be responsible, even if I must come to Priamos myself. Just get out of the area. You’ve already created enough trouble for yourself. Don’t finish ruining your cover.

No,Daniel sent. One look at that kalliran face of yours and you would never catch her. Send your ship. But you’ll do things on my terms.

There was no answer. Daniel looked up again at the star that was Ashanome.A second brilliant light had appeared not far from it; and a third, unmoving to the eye. They were simply there, and they had not been.

Aiela,he flung out toward the first star.

But this time Aiela shut him out.

The paredreblazed with light. The farthest side of it, bare of furniture, was suddenly occupied by consoles and screens and panels rippling with color. In the midst of it stood Chimele with her nas-katasakkeRakhi, and they spoke urgently of the startling appearance of two of the akitomei.The image of them hung three-dimensional in the cube of darkness on the table, projection within projection, mirror into mirror.

Suddenly there was only Chimele and the darker reality of the paredre.Aiela met her quick glance uneasily, for kamethi were not admitted to control stations.

“Isande has been summoned,” said Chimele. “Cast her the details of the situation here. Keep screening against Daniel. Are you strong enough to maintain that barrier?”

“Yes. Are we under attack?”

The thought seemed to surprise Chimele. “Attack? No. The nasuliare not prone to such inconsiderate action. This is harathos,the Observance. Tashavodhhas come to see vaikkadone, and Mijanotheis the neutral Observer, who will declare to all the nasulithat things were done rightly. This is expected, and unexpected. It might have been omitted. It would have pleased me if it had been.”

In his mind, Isande had already started for the door of her apartment, pulled her tousled head through the sweater; the sweater was tugged to rights, her thin-soled boots pattering quickly down the corridor. He fired her what information he could, coherent, condensed, as he had learned to do.

And Daniel?she asked in return. What has happened to him?

Her question almost disrupted his screening. He clamped down against it, too incoherent to screen against Daniel and explain about him at once. Isande understood, and he was about to reply again when he was startled by a projection appearing not a pace from him.

Mejakh!He jerked back even as he flashed the warning to Isande. His dealings with the mother of Khasif and Tejef had been blessedly few, but she came into the paredremore frequently now that other duties had stripped Chimele of the aid of her nasithi-katasakke—for Chaikhe’s pursuit of an iduve mate had rendered her katasatheand barred her from the paredre,Khasif and Ashakh were on Priamos, and poor Rakhi was on watch in the control room trying to manage all the duties of his missing nasithito Chimele’s demanding satisfaction. Mejakh accordingly asserted her rank as next closest, of an indirectly related sra,for Chimele had no other. Seeing that she had children now adult, she might be forty or more in age, but she had not the apologetic bearing of an aging female. She moved with the insolent grace of a much younger woman, for iduve lived long if they did not die by violence. She was slim and coldly handsome, commanding in her manner, although her attractiveness was spoiled by a rasping voice.

“Chimele,” said Mejakh, “I heard.”

Chimele might have acknowledged the offered support by some courtesy: iduve were normally full of compliments. All Mejakh received was a stare a presumptuous nas kame might have received, and that silence found ominous echo in the failure of Mejakh to lower her eyes. It was not an exchange an outsider would have noted; but Aiela had been long enough among iduve to feel the chill in the air.

“Chimele,” Rakhi said by intercom, “projections incoming from Tashavodhand Mijanothe.”

“Nine and ten clear, Rakhi.”

The projections took instant shape, edges blurred together, red background warring against violet. On the left stood a tall, wide-shouldered man, square-faced with frowning brows and a sullen mouth: Kharxanen,Isande read him through Aiela’s eyes, hate flooding with the name, memories of dead Reha, of Tejef, of Mejakh’s dishonor; he was Sogdrieni’s full brother, Tejef’s presumed uncle. The other visitor was a woman seated in a wooden chair, an iduve so old her hair had silvered and her indigo skin had turned fair—a little woman whose high cheek-bones, strong nose, and large, brilliant eyes gave her a look of ferocity and immense dignity. She was robed in black; a chromium staff lay across her lap. Somehow it did not seem incongruous that Chimele paid her deference in this her own ship.

“Thiane,” Isande voiced him in a tone of awe. “O be careful not to be noticed, Aiela. This is the president of the Orithanhe.”

“Hail Ashanome,” said Thiane in a soft voice. “Forgive an old woman her suddenness, but I have too few years left to waste long moments in hailings and well-wishing. There is no vaikkabetween us.”

“No,” said Chimele, “no, there is not. Thiane, be welcome. And for Thiane’s sake, welcome Kharxanen.”

“Hail Ashanome,” the big man said, bowing stiffly, “Honor to the Orithanhe, whose decrees are to be obeyed. And hail Mejakh, once of Tashavodh,less honored.”

Mejakh hissed delicately and Kharxanen smiled, directing himself back to Chimele.

“The infant the sraof Mejakh prospers,” he said. “‘The honor of us both has benefited by our agreement. I give you farewell, Ashanome:the call was courtesy. Now you know that I am here.”

“Hail Tashavodh,” Chimele said flatly, while Mejakh also flicked out, vanished with a shriek of rage, leaving Chimele, and Thiane, and Aiela, who stood in the shadows.

“ Au,” said Thiane, evidently distressed by this display, and Chimele bowed very low.

“I am ashamed,” said Chimele.

“So am I,” said Thiane.

“You are of course most welcome. We are greatly honored that you have made the harathosin person.”

“Chimele, Chimele—you and Kharxanen between you can bring three-quarters of the iduve species face to face in anger, and does that not merit my concern?”

“Eldest of us all, I am overwhelmed by the knowledge of our responsibility.”

“It would be an incalculable disaster. Should something go amiss here, I could bear the dishonor of it for all time.”

“Thiane,” said Chimele, “can you believe I would violate the terms? If I had wished vaikkawith Tashavodhto lead to catastrophe, would I have convoked the Orithanhe in the first place?”

“I see only this: that with less than three days remaining, I find you delaying further, I find you with this person Tejef within scan and untouched, and I suspect the presence of Ashanomepersonnel onworld. Am I incorrect, Chimele s ra-Chaxal?”

“You are quite correct, Thiane.”

“Indeed.” Her brows drew down fiercely and her old voice shook with the words. “Simple vaikkawill not do, then; and if you do miscalculate, Chimele, what then?”

“I shall take vaikkaall the same,” she answered, her face taut with restraint. “Even to the destruction of Priamos. The risk I run is to mine alone, and to do so is my choice, Thiane.”

“ Au,you are rash, Chimele. To destroy this world would have sufficed, although it is a faceless vaikka.You have committed yourself too far this time. You will lose everything.”

“That is mine to judge.”

“It is,” Thiane conceded, “until it comes to this point: that there be a day remaining, and you have not yet acted upon your necessities. Then I will blame you, that with Tashavodhstanding by in harathos,you would seem deliberately to provoke them to the last, threatening the deadline. There will be no infringement upon that, Chimele, not even in appearance. Any and all of your interference on Priamos will have ceased well ahead of that last instant, so that Tashavodhwill know that things were rightly done. I have responsibility to the Orithanhe, to see that this ends without further offense; and should offense occur, with great regret, Chimele, with great regret, I should have to declare that you had violated the decrees of the Orithanhe that forbade you vaikkaupon Tashavodhitself. Ashanomewould be compelled to surrender its Orithain into exile or be cast from the kindred into outlawry. You are without issue, Chimele. I need not tell you that if Ashanomeloses you, a dynasty more than twelve thousand years old ceases; that Ashanomefrom being first among the kindred becomes nothing. Is vaikkaupon this man Tejef of such importance to you, that you risk so much?”

“This matter has had Ashanomein turmoil from before I left the dhis,o Thiane; and if my methods hazard much, bear in mind that our primacy has been challenged. Does not great gain justify such risk?”

Thiane lowered her eyes and inclined her head respectfully. “Hail Ashanome.May your dhisincrease with offspring of your spirit, and may your sracontinue in honor. You have my admiration, Chimele. I hope that it may be so at our next meeting.”

“Honor to Mijanothe.May your dhisincrease forever.”

The projection vanished, and Chimele surrounded herself with the control room a brief instant, eyes flashing though her face was calm.

“Rakhi. Summon Ashakh up to Ashanomeand have him report to me the instant he arrives.”

Rakhi was still in the midst of his acknowledgment when Chimele cut him out and stood once more in the paredre.Isande, who had waited outside rather than break in upon Thiane, was timidly venturing into the room, and Chimele’s sweeping glance included both the kamethi.

“Take over the desk to the rear of the paredre.Review the status and positions of every amaut and mercenary unit on Priamos relative to Tejef’s estimated location. Daniel must be reassigned.”

Had it been any other iduve, even Ashakh, that so ordered him, Aiela would have cried out a reminder that he had been almost a night and a day without sleep, that he could not possibly do anything requiring any wit at all; but it was Chimele and it was for Daniel’s sake, and Aiela bowed respectfully and went off to do as he was told.

Isande touched his mind, sympathizing. “I can do most of it,” she offered. “Only you sit by me and help a little.”

He sat down at the desk and leaned his head against his hands. He thought again of Daniel, the anger, the hate of the being for him over that child. He could not persuade them apart; he had tried, and probably Daniel would not forgive him. Reason insisted, reason insisted: Daniel’s company itself was supremely dangerous to the child. They were each safer apart. Priamos was safer for it, he and the child hopeless of survival otherwise; leaving her was a risk, but it was a productive one. It was the reasonable, the orderly thing to do; and the human called him murderer, and shut him out, mind locked obstinately into some human logic that sealed him out and hated. His senses blurred. He shivered in a cool wind, realized the slip too late.