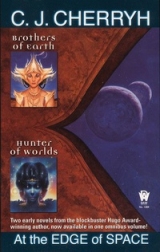

Текст книги "At the Edge of Space (Brothers of Worlds; Hunter of Worlds)"

Автор книги: C. J. Cherryh

Жанр:

Космическая фантастика

сообщить о нарушении

Текущая страница: 5 (всего у книги 36 страниц)

“Your friends of Elas are Indras. Did you know?”

“I had heard so, yes.”

“So are most of the Great Families of Nephane. The Indras established this as a colony once, when they conquered the inland fortress of Chteftikan and began to build this fortress with Sufaki slaves taken in that war. Indresul has no love of the Nephanite Indras, but she has never forgotten that through them she has a claim on this city. She wants it. I am walking a narrow line, Kurt Morgan, and your Indras friends in Elas and your own meddling in nemet affairs are an embarrassment to me at a time when I can least afford embarrassment. I need quiet in this city. I will do what is necessary to secure that.”

“I’ve done nothing,” he said, “except inside Elas.”

“Unfortunately,” said Djan, “Elas does nothing without consequence in Nephane. That is the misfortune of wealth and power.—That ship out there—is bound for Indresul. The Methi of Indresul has eluded my every attempt to talk. You cannot imagine how they despise Sufaki and humans. Well, at last they are going to send an ambassador,—one Mor t’Uset ul Orm, a councilor who has high status in Indresul. He will come at the return of that ship. And this betrothal of yours, publicized in the market today, had better not come to the attention of t’Uset when he arrives.”

“I have no desire to be noticed by anyone,” he said.

The glance she gave him was ice. But at that moment Pailechan and another girl pattered into the hall cat-footed and brought tea and teliseand a light supper, setting it on the low table by the ledge.

Djan dismissed them both, although strict formality dictated someone serve. The chanibowed themselves out.

“Join me,” she said, “in tea or telise,if nothing else.”

His appetite had returned somewhat. He picked at the food and then found himself hungry. He ate fully enough for his share, and demurred when she poured him telise,but she set the cup beside him. She carried the dishes out herself, returned and settled upon the ledge beside him. The ship had long since cleared the harbor, leaving its surface to the wind and the moon.

“It is late,” he said. “I would like to go back to Elas.”

“This nemet girl. What is her name?”

All at once the meal lay like lead at his stomach.

“What is her name?”

“Mim,” he said, and reached for the telise,swallowed some of its vaporous fire.

“Did you compromise the girl? Is that the reason for this sudden marriage?”

The cup froze in his hand. He looked at her, and all at once he knew she had meant it just as he had heard it, and flushed with heat, not the telise.

“I am in love with her.”

Djan’s cool eyes rested on him, estimating. “The nemet are a beautiful people. They have a certain attraction. And I suppose nemet women have a certain—flattering appeal to a man of our kind. They always let their men be right.”

“It will not trouble you,” he said.

“I am sure it will not.” She let the implied threat hang in the air a moment and then shrugged lightly. “I have nothing personal against the child. I don’t expect I’ll ever have to consider the problem. I trust your good sense for that. Marry her. Occasionally you will find, as I do, that nemet thoughts and looks and manners—and nemet prejudices—are too much for you. That fact moved me, I admit it, or you would be keeping company with the Tamurlin—or the fishes. I had rather think we were companions,—human and reasonably civilized. This person Mim, she is only chan;she does at least provide a certain respectability if you are careful. I suppose it is not such a bad choice, so I do not think this marriage will be such an inconvenience to me. And I think you understand me, Kurt.”

The cup shook in his hand. He put it aside, lest his fingers crush the fragile crystal.

“You are gambling your neck, Djan. I won’t be pushed.”

“I do not push,” she said, “more than will make me understood. And I think we understand each other plainly.”

7

The gray light of dawn was over Nephane, spreading through a mist that overlay all but the upper walls of the Afen. The cobbled street running down from the Afen gate was wet, and the few people who had business on the streets at that hour went muffled in cloaks.

Kurt stepped up to the front door of Elas, tried the handle in the quickly dashed hope that it would be unlocked, then knocked softly, not wanting to wake the whole house.

More quickly than he had expected, soft footsteps approached the door inside, hesitated. He stood squarely before the door to be surveyed from the peephole.

The bar flew back, the door was snatched inward, and Mim was there in her nightrobe. With a sob of relief she flung herself into his arms and hugged him tightly.

“Hush,” he said, “it’s all right; it’s all right, Mim.”

They were framed in the doorway. He brought her inside and closed and barred the heavy door. Mim stood wiping at her eyes with her wide sleeve.

“Is the house awake?” he whispered.

“Everyone finally went to bed. I came out again and waited in the rhmei.I hoped—I hoped you would come back. Are you all right, my lord?”

“I am well enough.” He took her in his arm and walked with her to the warmth of the rhmei.There in the light her large eyes stared up at him and her hands pressed his, gentle as the touch of wind.

“You are shaking,” she said. “Is it the cold?”

“It’s cold and I’m tired.” It was hard to slip back into Nechai after hours of human language. His accent crept out again.

“What did she want?”

“She asked me some questions. They held me all night—Mim, I just want to go upstairs and get some sleep. Don’t worry. I am well, Mim.”

“My lord,” she said in a tear-choked voice, “before the phusmehait is a great wrong to lie. Forgive me, but I know that you are lying.”

“Leave me alone, Mim, please.”

“It was not about the questions. If it was, look at me plainly and say that it was so.”

He tried, and could not. Mim’s dark eyes flooded with sadness.

“I am sorry,” was all that he could say.

Her hands tightened on his. That terrible dark-eyed look would not let him go. “Do you wish to break the contract, or do you wish to keep it?”

“Do you?”

“If it is your wish.”

With his chilled hand he smoothed the hair from her cheek and wiped at a streak of tears. “I do not love her,” he said; and then, tribute to the honesty Mim herself used: “But I know how she feels, Mim. Sometimes I feel that way too. Sometimes all Elas is strange to me and I want to be human just for a little time. It is like that with her.”

“She might give you children and you would be lord over all Nephane.”

He crushed her against him, the faint perfume of aluelleaves about her clothing, a freshness about her skin, and remembered the synthetics-and-alcohol scent of Djan, human and, for the moment, pleasing. There was kindness in Djan; it made her dangerous, for it threatened her pride.

It threatened Elas.

“If it were in Djan’s nature to marry, which it is not, I would still feel no differently, Mim. But I cannot say that this will be the last time I go to the Afen. If you cannot bear that, then tell me so now.”

“I would be concubine and not first wife, if it was your wish.”

“No,” he said, realizing how she had heard it. “No, the only reason I would ever put you aside would be to protect you.”

She leaned up on tiptoe and took his face between her two silken hands, kissed him with great tenderness. Then she drew back, hands still uplifted, as if unsure how he would react. She looked frightened.

“My lord husband,” she said, which she was entitled to call him, being betrothed. The words had a strange sound between them. And she took liberties with him which he understood no honorable nemet lady would take with her betrothed, even in being alone with him. But she put all her manners aside to please him,—perhaps, he feared, to fight for him in her own desperate fashion.

He pressed her to him tightly and set her back again. “Mim, please. Go before someone wakes and sees you. I have to talk to Kta.”

“Will you tell him what has happened?”

“I intend to.”

“Please do not bring violence into this house.”

“Go on, Mim.”

She gave him an agonized look, but she did as he asked her.

He did not knock at Kta’s door. There had already been too much noise in the sleeping house. Instead he opened it and slipped inside, crossed the floor and parted the curtain that screened the sleeping area before he spoke Kta’s name.

The nemet came awake with a start and an oath, looked at Kurt with dazed eyes, then rolled out of bed and wrapped a kilt around himself. “Gods,” he said, “you look deathly, friend. What happened? Are you all right? Is there some—?”

“I’ve just been put to explaining a situation to Mim,” Kurt said, and found his limbs shaking under him, the delayed reaction to all that he had been through. “Kta, I need advice.”

Kta showed him a chair. “Sit down, my friend. Compose your heart and I will help you if you can make me understand. Shall I find you something to drink?”

Kurt sat down and bowed his head, locked his fingers behind his neck until he made himself remember the calm that belonged in Elas. The scent of incense, the dim light of the phusa,the sense of stillness, all this comforted him, and the panic left him though the fear did not.

“I am all right,” he said. “No, do not bother about the drink.”

“You only now came in?” Kta asked him, for the morning showed through the window.

Kurt nodded, looked him in the eyes, and Kta let the breath hiss slowly between his teeth.

“A personal matter?” Kta asked with admirable delicacy.

“The whole of Elas seemed to have read matters better than I did when I went up to the Afen. Was it that obvious? Does the whole of Nephane know by now, or is there any privacy in this city?”

“Mim knew, at least. Kurt, Kurt, light of heaven, there was no need to guess. When the Methi’s men came back to assure us of your safety, it was clear enough, coupled with the Methi’s reaction to the betrothal. My friend, do not be ashamed. We always knew that your life would be bound to that of the Methi. Nephane has taken it for granted from the day you came. It was the betrothal to Mim that shocked everyone—I am speaking plainly. I think the truth has its moment, even if it is bitter. Yes, the whole of Nephane knows, and is by no means surprised.”

Kurt swore, a raw and human oath, and gazed off at the window, unable to look at the nemet.

“Have you,” said Kta, “love for the Methi?”

“No,” he said harshly.

“You chose to go,” Kta reminded him, “when Elas would have fought for you.”

“Elas has no place in this.”

“We have no honor if we let you protect us in this way. But it is not clear to us what your wishes are in this matter. Do you wish us to intervene?”

“I do not wish it,” he answered.

“Is this the wish of your heart? Or do you still think to shield us? You owe us the plain truth, Kurt. Tell us yes or no and we will believe your word and do as you wish.”

“I do not love the Methi,” he said in a still voice, “but I do not want Elas involved between us.”

“That tells me nothing.”

“I expect,” he said, finding it difficult to meet Kta’s dark-eyed and gentle sympathy, “that it will not be the last time. I owe her, Kta. If my behavior offends the honor of Elas or of Mim, tell me. I have no wish to bring misery on this house, and least of all on Mim. Tell me what to do.”

“Life,” said Kta, “is a powerful urge. You protest you hate the Methi, and perhaps she hates you, but the urge to survive and perpetuate your kind—may be a sense of honor above every other honor. Mim has spoken to me of this.”

He felt a deep sickness, thinking of that. At the moment he himself did not even wish to survive.

“Mim honors you,” said Kta, “very much. If your heart toward her changed, still,—you are bound, my friend. I feared this; and Mim foreknew it. I beg you do not think of breaking this vow with Mim; it would dishonor her. Ai,my friend, my friend, we are a people that does not believe in sudden marriage, yet for once we were led by the heart, we were moved by the desire to make you and Mim happy. Now I hope that we have not been cruel instead. You cannot undo what you have done with Mim.”

“I would not,” Kurt said. “I would not change that.”

“Then,” said Kta, “all is well.”

“I have to live in this city,” said Kurt, “and how will people see this and how will it be for Mim?”

Kta shrugged. “This is the Methi’s problem. It is common for a man to have obligations to more than one woman. One cannot, of course, have the Methi of Nephane for a common concubine. But it is for the woman’s house to see to the proprieties and to obtain respectability. An honorable woman does so, as we have done for Mim. If a woman will not, or her family will not, matters are on her head, not yours. Though,” he added, “a Methi can do rather well as he or she pleases, and this has been a common difficulty with Methis, particularly with human ones,—and the late Tehal-methi of Indresul was notorious. Djan-Methi is efficient. She is a good Methi. The people have bread and peace, and as long as that lasts, you can only obtain honor by your association with her. I am only concerned that your feelings may turn again to human things, and Mim be only of a strange people that for a time entertained you.”

“No.”

“I beg your forgiveness if this would never happen.”

“It would never happen.”

“I have offended my friend,” said Kta. “I know you have grown nemet, and this part of you I trust; but forgive me: I do not know how to understand the other.”

“I would do anything to protect Mim—or Elas.”

“Then,” said Kta in great earnestness, “think as nemet, not as human. Do nothing without your family. Keep nothing from your family. The Families are sacred. Even the Methi is powerless to do you harm when you stand with us and we with you.”

“Then you do not know Djan.”

“There is the law, Kurt. So long as you have not taken arms against her or directly defied her, the law binds her. She must go through the Upei, and a dispute—forgive me—with her lover—is hardly the kind of matter she could lay before the Upei.”

“She could simply assign you and Tavito sail to the end of the known world. She has alternatives, Kta.”

“If the Methi chooses a quarrel with Elas,” said Kta, “she will have chosen unwisely. Elas was here before the Methi came, and before the first human set foot on this soil. We know our city and our people, our voice is heard in councils on both sides of the Dividing Sea. When Elas speaks in the Upei, the Great Families listen; and now of all times the Methi dares not have the Great Families at odds with her. Her position is not as secure as it seems, which she knows full well, my friend.”

8

The ship from Indresul came into port late on the day scheduled, a bireme with a red sail—the international emblem, Kta explained as he stood with Kurt on the dock, of a ship claiming immunity from attack. It would be blasphemy against the gods either to attack a ship bearing that color or to claim immunity without just cause.

The Nephanite crowds were ominously silent as the ambassador left his ship and came ashore. Characteristic of the nemet, there was no wild outburst of hatred, but people took just long enough moving back to clear a path for the ambassador’s escort to carry the point that he was not welcome in Nephane.

Mor t’Uset ul Orm, white-haired and grim of face, made his way on foot up the hill to the height of the Afen and paid no heed to the soft curses that followed at his back.

“The house of Uset,” said Kta as he and Kurt made their way uphill in the crowd, “that house on this side of the Dividing Sea, will not stir out of doors this day. They will not go into the Upei for very shame.”

“Shame before Mor t’Uset or before the people of Nephane?”

“Both. It is a terrible thing when a house is divided. The Guardians of Uset on both sides of the sea are in conflict. Ei, ei,fighting the Tamurlin is joyless enough; it is worse that two races have warred against each other over this land; but when one thinks of war against one’s own family, where gods and Ancestors are shared, whose hearth once burned with a common flame,– ai,heaven keep us from such a day.”

“I do not think Djan will take this city to war. She knows too well where it leads.”

“Neither side wants it,” said Kta, “and the Indras-descended of Nephane want it least of all. Our quarrel with—”

Kta fell silent as they came to the place where the street narrowed to pass the gate in the lower defense wall. A man reaching the gate from the opposite direction was staring at them—tall, powerful, wearing the braid and striped robe that was not uncommon in the lower town and among the Methi’s guard.

All at once Kurt knew him. Shan t’Tefur. Hate seemed in permanent residence in t’Tefur’s narrow eyes. For a moment Kurt’s heart pounded and his muscles tensed, for t’Tefur had stopped in the gate and seemed about to bar their way.

Kta jostled against Kurt, purposefully, clamped his arm in a hard grip unseen beneath the fold of the ctanand edged him through the gate, making it clear he should not stop.

“That man,” said Kurt, resisting the urge to look back, for Kta’s grip remained hard, warning him. “That man is from the Afen.”

“Keep moving,” Kta said.

They did not stop until they reached the high street, that area near the Afen which belonged to the mansions of the Families, great, rambling things, among which Elas was one of the most prominent. Here Kta seemed easier, and slowed his pace as they headed toward the door of Elas.

“That man,” Kurt said then, “came where I was being held in the Afen. He brought me into the Methi’s rooms. His name is t’Tefur.”

“I know his name.”

“He seems to have a dislike for humans.”

“Hardly,” said Kta. “It is a personal dislike. He has no fondness for either of us. He is Sufaki.”

“I noticed—the braid, the robes,—that is not the dress of the Methi’s guard, then?”

“No. It is Sufak.”

“Osanef—Osanef is Sufaki. Han t’Osanef and Bel do not wear—”

“No. Osanef is Sufaki, but the jafikn,that long hair braided in the back, that is an ancient custom: the warrior’s braid. No one has done it since the Conquest. It was forbidden the Sufaki then. But in recent years the rebel spirits have revived the custom—and the Robes of Color, which distinguish their houses. There are three Sufak houses of the ancient aristocracy surviving, and t’Tefur is of one. He is a dangerous man. His name is Shan t’Tefur u Tlekef, or as he prefers to be known—Tlekefu Shan Tefur. He is Elas’ bitter enemy, and he is yours, not alone for the sake of Elas.”

“Because I’m human? But I understood Sufaki had no particular hate for—” And it dawned on him, with a sudden heat of the face.

“Yes,” said Kta, “he has been the Methi’s lover for many months.”

“What—does your custom say he and I should do about it?”

“Sufak custom says he may try to make you fight him. And you must not. Absolutely you must not.”

“Kta, I may be helpless in most things nemet, but if he wants to press a fight, that is something I can understand. Do you mean a fight, or do you mean a fight to the death? I am not that anxious to kill him over her, but neither am I going to be—”

“Listen. Hear what I am saying to you. You must avoid a fight with him. I do not question your courage or your ability. I am asking this for the sake of Elas. Shan t’Tefur is dangerous.”

“Do you expect me to allow myself to be killed? Is he dangerous in that sense, or how?”

“He is a power among the Sufaki. He sought more power, which the Methi could give him. You have made him lose honor and you have threatened his position of leadership. You are resident with Elas, and we are of the Indras-descended. Until now, the Methi has inclined toward the Sufaki, ever since she dispensed with me as an interpreter. She has been surrounded by Sufaki, chosen friends of Shan t’Tefur, and has drawn much of her power from them, so much so that the Great Families are uneasy. But of a sudden Shan t’Tefur finds his footing unsteady.”

They walked in silence for a moment. Increasingly bitter and embarrassed thoughts reared up. Kurt glanced at the nemet. “You pulled me from the harbor. You saved my life. You gave me everything I have—by Djan’s leave. You went to her and asked for me, and if not for that—I would be—I would certainly not be walking the streets free. So do not misunderstand what I ask you. But you said that from the time I arrived in Nephane, people knew that I would become involved with the Methi. Was I pushed toward that, Kta? Was I aimed at her,—an Indras weapon—against Shan t’Tefur?”

And to his distress, Kta did not answer at once.

“Is it the truth, then?” Kurt asked.

“Kurt, you have married within my house.”

“Is it true?” he insisted.

“I do not know how a human hears things,” Kta protested. “Or whether you attribute to me motives no nemet would have, or fail to think what would be obvious to a nemet. Gods, Kurt—”

“Answer me.”

“When I first saw you—I thought—He is the Methi’s kind. Is that not most obvious? Is there offense in that? And I thought: He ought to be treated kindly, since he is a gentle being, and since one day he may be more than he seems now. And then an unworthy thought came to me: It would be profitable to your house, Kta t’Elas. And there is offense in that. At the time you were only human to me; and to a nemet, that does not oblige one to deal morally. I do offend you. I cause you pain. But that is the way it was. I think differently now. I am ashamed.”

“So Elas took me in,—to use.”

“No,” said Kta quickly. “We would never have opened—”

His words died as Kurt kept staring at him. “Go ahead,” said Kurt. “Or do I already understand?”

Kta met his eyes directly, contrition in a nemet. “Elas is holy to us. I owe you a truth. We would never have opened our doors to you—to anyone—Very well, I will say it: it is unthinkable that I would have exposed my hearth to human influence, whatever the advantage is promised with the Methi. Our hospitality is sacred, and not for sale for any favor. But I made a mistake—in my anxiousness to win your favor, I gave you my word; and the word of Elas is sacred too. So I accepted you. My friend, let our friendship survive this truth: when the other Families reproached Elas for taking a human into its rhmei,we argued simply that it was better for a human to be within an Indras house than that you be sent to the Sufaki instead, for the influence of the Sufaki is already dangerously powerful. And I think another consideration influenced Djan-methi in hearing me: that your life would have been in constant danger in a Sufak house, because of the honor of Shan t’Tefur,—although I dared not say it in words. So she sent you to Elas. I think she feared t’Tefur’s reaction even if you remained in the Afen.”

“I understand,” said Kurt, because it seemed proper to say something. The words hurt. He did not trust himself to say much.

“Elas loves and honors you,” said Kta, and when Kurt still failed to answer him he looked down, and with what appeared much thought, he cautiously extended his hand to take his arm, touching like Mim, with feather-softness. It was an unnatural gesture for the nemet; it was one studied, copied, offered now on the public street as an act of desperation.

Kurt stopped perforce, set his jaw against the tears which threatened.

“Avoid t’Tefur,” Kta pleaded. “If the housefriend of Elas kills the heir of Tefur,—or if he kills you—killing will not stop there. He will provoke you if he can. Be wise. Do not let him do this.”

“I understand. I have told you that.”

Kta glanced down, gave the sketch of a bow. The hand dropped. They walked on, near to Elas.

“Have I a soul?” Kurt asked him suddenly, and looked at him.

The nemet’s face was shocked, frightened.

“Have I a soul?” Kurt asked again.

“Yes,” said Kta, which seemed difficult for him to say.

It was, Kurt thought, an admission which had already cost Kta some of his peace of mind.

The Upei, the council, met that day in the Afen and adjourned, as by law it must, as the sun set, to convene again at dawn.

Nym returned to the house at dusk, greeted lady Ptas and Hef at the door. When he came into the rhmeiwhere the light was, the senator looked exhausted, utterly drained. Aimu hastened to bring water for washing, while Ptas prepared the tea.

There was no discussion of business during the meal. Such matters as Nym had on his mind were reserved for the rounds of tea that followed. Instead Nym asked politely after Mim’s preparation for her wedding, and for Aimu’s, for both were spending their days sewing, planning, discussing the coming weddings, keeping the house astir with their happy excitement and sometimes tears, and Aimu glanced down prettily and said that she had almost completed her own trousseau and that they were working together on Mim’s things, for, Aimu thought, their beloved human was not likely to choose the long formal engagement such as she had had with Bel.

“I met our friend the elder t’Osanef,” said Nym in answer to that, “and it is not unlikely, little Aimu, that we will advance the date of your own wedding.”

“ Ei,” murmured Aimu, her dark eyes suddenly wide. “How far, honored Father?”

“Perhaps within a month.”

“Beloved husband,” exclaimed Ptas in dismay, “such haste?”

“There speaks a mother,” Nym said tenderly. “Aimu, child, do you and Mim go fetch another pot of tea. And then go to your sewing. There is business afoot hereafter.”

“Shall I—?” asked Kurt, offering by gesture to depart.

“No, no, our guest. Please sit with us. This business concerns the house, and you are soon to be one of us.”

The tea was brought and served with all formality. Then Mim and Aimu withdrew, leaving the men of the house and Ptas. Nym took a slow sip of tea and looked at his wife.

“You had a question, Ptas?”

“Who asked the date advanced? Osanef? Or was it you?”

“Ptas, I fear we are going to war.” And in the stillness that awful word made in the room he continued very softly: “If we wish this marriage I think we must hurry it on with all decent speed; a wedding between Sufaki and Indras may serve to heal the division between the Families and the sons of the east; that is still our hope. But it must be soon.”

The lady of Elas wept quiet tears and blotted them with the edge of her scarf. “What will they do? It is not right, Nym, it is not right that they should have to bear such a weight on themselves.”

“What would you? Break the engagement? That is impossible. For us to ask that—no. No. And if the marriage is to be, then there must be haste. With war threatening,—Bel would surely wish to leave a son to safeguard the name of Osanef. He is the last of his name. As you are, Kta, my son. I am above sixty years of age, and today it has occurred to me that I am not immortal. You should have laid a grandson at my feet years ago.”

“Yes, sir,” said Kta quietly.

“You cannot mourn the dead forever; and I wish you would make some choice for yourself, so that I would know how to please you. If there is any young woman of the Families who has touched your heart—”

Kta shrugged, looking at the floor.

“Perhaps,” his father suggested gently, “the daughters of Rasim or of Irain ...”

“Tai t’Isulan,—” said Kta.

“A lovely child,” said Ptas, “and she will be a fine lady.”

Again Kta shrugged. “A child, indeed. But I do at least know her, and I think I would not be unpleasing to her.”

“She is—what?—seventeen?” asked Nym, and when Kta agreed: “Isulan is a fine religious house. I will think on it and perhaps I will talk with Ban t’Isulan, if in several days you still think the same.—My son, I am sorry to bring this matter upon you so suddenly, but you are my only son, and these are sudden times. Ptas, pour some telise.”

She did so. The first few sips were drunk in silence. This was proper. Then Nym sighed softly.

“Home is very sweet, wife. May we abide as we are tonight.”

“May it be so,” reverently echoed Ptas, and Kta did the same.

“The matter in council,” said Ptas then. “What was decided?”

Nym frowned and stared at nothing in particular. “T’Uset is not here to bring peace, only more demands of the Methi Ylith. Djan-methi was not in the Upei today; it did not seem wise. And I suspect—” His eyes wandered to Kurt, estimating; and Kurt’s face went hot. Suddenly he gathered himself to leave, but Nym forbade that with a move of his hand, and he settled again, bowing low and not meeting Nym’s eyes.

“Our words could offend you,” said Nym. “I pray not.”

“I have learned,” said Kurt, “how little welcome my people have made for themselves among you.”

“Friend of my son,” said Nym gently, “your wise and peaceful attitude is an ornament to this house. I will not affront you by repeating t’Uset’s words. Reason with him proved impossible: the Indras of the mother city hate humans, and they will not negotiate with Djan-methi. And that is not the end of our troubles.” His eyes sought Ptas. “T’Tefur created bitter discussion, even before t’Uset was seated, demanding we not permit him to be present during the Invocation.”

“Light of heaven,” murmured Ptas. “In t’Uset’s hearing?”

“He was at the door.”

“We met the younger t’Tefur today,” said Kta. “There were no words, but his manner was deliberate and provocative, aimed at Kurt.”

“Is it so?” said Nym, concerned, and with a glance at Kurt: “Do not fall into his hands. Do not place yourself where you can become a cause, our friend.”

“I am warned,” said Kurt.

“Today,” said Nym, “there was a curse spoken between the house of Tefur and the house of Elas, before the Upei, and we must all be on our guard. T’Tefur blasphemed, shouting down the Invocation, and I answered him as his behavior deserved. He calls it treason, that when we pray we still call on the name of Indresul the shining. This he said in t’Uset’s hearing.”

“And for the likes of this,” said lady Ptas, “we must endure to be cursed from the hearthfire of Elas-in-Indresul, and have our name pronounced annually in infamy at the Shrine of Man.”

“Mother,” said Kta, bowing low, “not all Sufaki feel so. Bel would not feel this way. He would not.”

“T’Tefur’s number is growing,” said Ptas, “that he dares to stand in the Upei and say such a thing.”