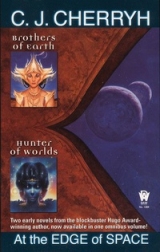

Текст книги "At the Edge of Space (Brothers of Worlds; Hunter of Worlds)"

Автор книги: C. J. Cherryh

Жанр:

Космическая фантастика

сообщить о нарушении

Текущая страница: 6 (всего у книги 36 страниц)

Kurt looked from one to the other in bewilderment. It was Nym who undertook to explain to him. “We are Indras. A thousand years ago Nai-methi of Indresul launched colonies toward the Isles, south of this shore, then laid the foundations of Nephane as a fortress to guard the coast from Sufaki pirates. He destroyed Chteftikan, the capital of the Sufaki kingdom, and Indras colonists administered the new provinces from this citadel. For most of time we ruled the Sufaki. But the coming of humans cut our ties to Indresul, and when we came out of those dark years, we wiped out all the cruel laws that kept the Sufaki subject, accepted them into the Upei. For t’Tefur, that is not enough. There is great bitterness there.”

“It is religion,” said Ptas. “Sufaki have many gods, and believe in magic and worship demons. Not all. Bel’s house is better educated. But Indras will not set foot in the precincts of the temple, the so-named Oracle of Phan. And it would be dangerous in these times even to be there in the wall-street after dark. We pray at our own hearths and invoke the Ancestors we have in common with the houses across the Dividing Sea. We do them no harm—we inflict nothing on them, but they resent this.”

“But,” said Kurt, “you do not agree with Indresul.”

“It is impossible,” said Nym. “We are of Nephane. We have lived among Sufaki; we have dealt with humans. We cannot unlearn the things we know for truth. We will fight if we must, against Indresul. The Sufaki seem not to believe that, but it is so.”

“No,” said Kurt, and with such passion that the nemet were hushed. “No. Do not go to war.”

“It is excellent advice,” said Nym after a moment. “But we may be helpless to guide our own affairs. When a man finds his affairs without resolution, his existence out of time with heaven and his very being a disturbance to the yhia,then he must choose to die for the sake of order. He does well if he does so without violence. In the eyes of heaven even nations are finally answerable to such logic, and even nations may sometimes be compelled to suicide. They have their methods,—being many minds and not one, they cannot proceed toward their fate with the dignity a single man can manage, but proceed they do.”

“ Ei,honored Father,” said Kta, “I beg you not to say such things.”

“Like Bel, do you believe in omens? I do not,—not, at least, that words, ill-thought or otherwise, have power over the future. The future already exists, in our hearts already, stored up and waiting to unfold when we reach our time and place. Our own nature is our fate. You are young, Kta. You deserve better than my age has given you.”

There was silence in the rhmei.Suddenly Kurt bowed himself a degree lower, requesting, and Nym looked at him.

“You have a Methi,” said Kurt, “who is not willing to fight a war. Please. Trust me to go speak to her, as another human.”

There was a stir of uneasiness. Kta opened his mouth as if he would protest, but Nym consented.

“Go,” he said, nothing more.

Kurt rose and adjusted his ctan,pinning it securely. He bowed to them collectively and turned to leave. Someone hurried after; he thought it was Hef, whose duty it was to tend the door. It was Kta who overtook him in the outer hall.

“Be careful,” Kta said. And when he opened the outer door into the dark: “Kurt, I will walk to the Afen with you.”

“No,” said Kurt. “Then you would have to wait there, and you would be obvious at this hour. Let us not make this more obvious than need be.”

But there was, once the door was closed and he was on the street in the dark, an uneasy feeling about the night. It was quieter than usual. A man muffled in striped robes stood in the shadows of the house opposite. Kurt turned and walked quickly uphill.

Djan put her back to the window that overlooked the sea and leaned back against the ledge, a metallic form against the dark beyond the glass. Tonight she dressed as human, in a dark blue form-fitting synthetic that shimmered like powdered glass along the lines of her figure. It was a thing she would not dare wear among the modest nemet.

“The Indras ambassador sails tomorrow,” she said. “Confound it, couldn’t you have waited? I’m trying to keep humanity out of his sight and hearing as much as possible, and you have to be walking up and down the halls—He’s staying on the floor just below. If one of his staff had come out—”

“This isn’t a social call.”

Djan expelled her breath slowly, nodded him toward a seat near her. “Elas and the business in the Upei. I heard. What did they send you to say?”

“They didn’t send me. But if you have any means of controlling the situation, you’d better exert it,—fast.”

Her cool green eyes measured him, centered soberly on his. “You’re scared. What Elas said must have been considerable.”

“Stop putting words in my mouth. There’s going to be nothing left but Indresul to pick up the pieces if this goes on. There was some kind of balance here, Djan. There was stability. You blew it to—”

“Nym’s words?”

“No. Listen to me.”

“There was a balance of power, yes,” Djan said. “A balance tilted in favor of the Indras and against the Sufaki. I have done nothing but use impartiality. The Indras are not used to that.”

“Impartiality. Do you maintain that with Shan t’Tefur?”

Her head went back. Her eyes narrowed slightly, but then she grinned. She had a beautiful smile, even when there was no humor in it. “Ah,” she said. “I should have told you. Now your feelings are ruffled.”

“I’m sure I don’t care,” he said, started to add something more cutting still, and then regretted even what he had said. He had, after a fashion, cared; perhaps she had feelings for him also. There was anger in her eyes, but she did not let it fly.

“Shan,” she said, “is a friend. His family were lords of this land once. He thinks he can bend me to his ambitions, which are probably considerable, and he is slowly learning he can’t. He is angry about your presence, which is an anger that will heal. I believe him about as much as I believe you when your own interests are at stake. I weigh all that either of you says, and try to analyze where the bias lies.”

“Being yourself perfect, of course.”

“In this government there does not have to be a Methi. Methis serve when it is useful to have one—In times of crisis, to bind civil and military authority into one swiftly-moving whole. My reason for being is somewhat different. I am Methi precisely because I am neither Sufaki nor Indras. Yes, the Sufaki support me. If I stepped down, the Indras would immediately appoint an Indras Methi. The Upei is Indras: nobility is the qualification for membership, and there are only three noble houses of the Sufaki surviving. The others were massacred a thousand years ago. Now Elas is marrying a daughter into one—so Osanef too becomes a limb of the Families. The Upei makes the laws: and the Assembly may be Sufaki, but all they can do is vote yea or nay on what the Upei deigns to hand them. The Assembly hasn’t rallied to veto anything since the day of its creation. So what else do the Sufaki have but the Methi? Oppose the Families by veto in the Assembly? Hardly likely, when the living of the Sufaki depend on big shipping companies like Irain and Ilev and Elas. A little frustration burst out today. It was regrettable. But if it makes the Families realize the seriousness of the situation, then perhaps it was well done.”

“It was not well done,” Kurt said. “Not when it was done, nor where it was done, nor against what it was done. The ambassador witnessed it. Did your informants tell you that detail? Djan, your selective blindness is going to make chaos out of this city. Listen to the Families. Call in their Fathers. Listen to them as you listen to Shan t’Tefur.”

“Ah, so it does rankle.”

He stood up. She resented his speaking to her. It had been on the edge of every word. It was in his mind to walk out, but that would let her forget everything he had said. Necessity overcame his pride. “Djan. I have nothing against you. In spite of—because of—what we did one night, I have a certain regard for you. I had some hope you might at least listen to me, for the sake of all concerned.”

“I will look into it,” she said. “I will do what I can.” And when he turned to go: “I hear little from you. Are you happy in Elas?”

He looked back, surprised by the gentleness of her asking. “I am happy,” he said.

She smiled. “In some measure I do envy you.”

“The same choices are open to you.”

“No,” she said. “Not by nemet law. Think of me and think of your little Mim, and you will know what I mean. I am Methi. I do as I please. Otherwise this world would put bonds on me that I couldn’t live with. It would make your life miserable if you had to accept such terms as this world would offer me. I refuse.”

“I understand,” he said. “I wish you well, Djan.”

She let the smile grow sad, and stared out at the lights of Nephane a moment, ignoring him.

“I am fond of few people,” she said. “In your peculiar way you have gotten into my affections,—more than Shan, more than most who have their reason for using me. Get out of here, back to Elas, discreetly. Go on.”

9

The wedding Mim chose was a small and private one. The guests and witnesses were scarcely more numerous than what the law required. Of Osanef, there was Han t’Osanef u Mur, his wife Ia t’Nefak, and Bel. Of the house of Ilev there was Ulmar t’Ilev ul Imetan and his wife Tian t’Elas e Ben, cousin to Nym, and their son Cam and their new daughter-in-law, Yanu t’Pas. They were all people Mim knew well, and Osanef and Ilev, Kurt suspected, were among a very few nemet houses that could be found reconciled to the marriage on religious grounds.

If even these had scruples about the question, they had the grace still to smile and to love Mim and to treat her chosen husband with great courtesy.

The ceremony was in the rhmei,where Kurt first knelt before old Hef and swore that the first two sons of the union, if any, would be given the name h’Elas as chanito the house, so that Hef’s line could continue.

And Kta swore also to the custom of iquun,by which Kta would see to the begetting of the promised heirs, if necessary.

Then Nym rose and with palms toward the light of the phusmehainvoked the guardian spirits of the Ancestors of Elas. The sun outside was only beginning to set. It was impossible to conduct a marriage-rite after Phan had left the land.

“Mim,” said Nym, taking her hand, “called Mim-lechan h’Elas e Hef, you are chanto this house no longer, but become as a daughter of this house, well-beloved, Mim h’Elas e Hef. Are you willing to yield your first two sons to Hef, your foster-father?”

“Yes, my lord of Elas.”

“Are you consenting to all the terms of the marriage contract?”

“Yes, my lord of Elas.”

“Are you willing now, daughter to Elas, to bind yourself by these final and irrevocable vows?”

“Yes, my lord of Elas.”

“And you, Kurt Liam t’Morgan u Patrick Edward, are you willing to bind yourself by these final and irrevocable vows, to take this free woman Mim h’Elas e Hef for your true and first wife, loving her before all others, commiting your honor into her hands and your strength and fortune to her protection?”

“Yes, my lord.”

“Hef h’Elas,” said Nym, “the blessing of this house and its Guardians upon this union.”

The old man came forward, and it was Hef who completed the ceremony, giving Mim’s hand into Kurt’s and naming for each the final vows they made. Then, according to custom, Ptas lit a torch from the great phusmehaand gave it into Kurt’s hands, and he into Mim’s.

“In purity I have given,” Kurt recited the ancient formula in High Nechai, “in reverence preserve, Mim h’Elas e Hef shu-Kurt, well-beloved, my wife.”

“In purity I have received,” she said softly, “in reverence I will keep myself to thee to the death, Kurt Liam t’Morgan u Patrick Edward, my lord, my husband.”

And with Mim beside him, and to the ritual weeping of the ladies and the congratulations of the men, Kurt left the rhmei.Mim carried the light, walking behind him up the stairs to the door of his room that now was hers.

He entered, and watched as she used the torch to light the triangular bronze lamp, the phusa,which had been replaced in its niche, and he heard her sigh softly with relief, for the omen would have been terrible if the light had not taken. The lamp of Phan burned with steady light, and she then extinguished the torch with a prayer and knelt down before the lamp as Kurt closed the door, knelt down and lifted her hands before it.

“My Ancestors, I, Mim t’Nethim e Sel shu-Kurt, called by these my beloved friends Mim h’Elas, I, Mim, beg your forgiveness for marrying under a name not my own, and swear now by my own name to honor the vows I made under another. My Ancestors, behold this man, my husband Kurt t’Morgan, and whatever distant spirits are his, be at peace with them for my sake. Peace, I pray my Fathers, and let peace be with Elas on both sides of the Dividing Sea. Ei,let thoughts of war be put aside between our two lands. May love be in this house and upon us both forever. May the terrible Guardians of Nethim hear me and receive the vow I make. And may the great Guardians of Elas receive me kindly as you have ever done, for we are of this house now, and within your keeping.”

She lowered her hands, finishing her prayer, and offered her right hand to Kurt, who drew her up.

“Mim t’Nethim,” he said. “Then I had never heard your real name.”

Her large eyes lifted to him. “Nethim has no house in Nephane, but in Indresul we are ancestral enemies to Elas. I have not burdened Kta with knowing my true name. He asked me, and I would not answer, so surely he suspects that I am of a hostile house; but if there is any harm in my silence, it is upon me only. And I have spoken your name before the Guardians of Nethim many times, and I have not felt that they are distressed at you, my lord Kurt.”

He had started to take her in his arms, but hesitated now, held his hands a little apart from her, suddenly fearing Mim and her strangeness. Her gown was beautiful and had cost days of work which he had watched; he did not know how to undo it, or if this was expected of him. And Mim herself was as complex and unknowable, wrapped in customs for which Kta’s instructions had not prepared him.

He remembered the frightened child that Kta had found among the Tamurlin, and feared that she would suddenly see him as human and loathe him, without the robes and the graces that made him—outwardly—nemet.

“Mim,” he said. “I would never see any harm come to you.”

“It is a strange thing to say, my lord.”

“I am afraid for you,” he said suddenly. “Mim, I do love you.”

She smiled a little, then laughed, down-glancing. He treasured the gentle laugh: it was Mim at her prettiest. And she slipped her hands about his waist and hugged him tightly, her strong slim arms dispelling the fear that she would break.

“Kurt,” she said, “Kta is a dear man, most honored of me. I know that you and he have spoken of me. Is this not so?”

“Yes,” he said.

“Kta has spoken to me too: he fears for me. I honor his concern. It is for both of us. But I trust your heart where I do not know your ways; I know if ever you hurt me, it would be much against your will.” She slipped her warm hands to him. “Let us have tea, my husband, a first warming of our hearth.”

That was much against his will, but it pleased her. She lit the small room-stove, which also heated, and boiled water and made them tea, which they enjoyed sitting on the bed together.

He had little to say but much on his mind; neither did Mim, but she looked often at him.

“Is it not enough tea?” he asked finally, with the same patient courtesy he always used in Elas, which Kta had taught his unwilling spirit. But this time there was great earnestness in the question, which brought a sly smile from Mim.

“What is your custom now?” she asked of him.

“What is yours?” he asked.

“I do not know,” she admitted, down-glancing and seeming distressed. Then for the first time he realized, and felt pained for his thoughtlessness: she had never been with a man of her own kind,—nor with any man of decency.

“Put up the teacups,” he said, “and come here, Mim.”

The light of morning came through the window and Kurt stirred in his sleep, his hand finding the smoothness of Mim beside him, and he opened his eyes and looked at her. Her eyes were closed, her lashes dark and heavy on her golden cheek, her full lips relaxed in dreams. A little scar marred her temple, as others not so slight marked her back and hips, and that anyone could have abused Mim was a thought he could not bear.

He moved, leaned on his arm across her and touched his lips to hers, smoothed aside the dark and shining veil of hair that flowed across her and across the pillows, and she stirred, responding sweetly to his morning kiss.

“Mim,” he said, “good morning.”

Her arms went around his neck. She pulled herself up and kissed him back. Then she blinked back tears, which he made haste to wipe away.

“Mim?” he questioned her, much troubled; but she smiled at him and even laughed.

“Dear Kurt,” she said, holding his face between her hands. And then, breaking for the side of the bed, she began to wriggle free. “ Ei, ei,my lord, I must hurry,—you must hurry—the sun is up. The guests will be waiting.”

“Guests?” he echoed, dismayed. “Mim—”

But she was already slipping into her dressing gown, then pattering away into the bath. He heard her putting wood into the stove.

“It is custom,” she said, putting her head back through the doorway of the bath. “They come back at dawn to breakfast with us.—Oh please, Kurt, please, hurry to be ready. They will be downstairs already, and if we are much past dawning, they will laugh.”

It was the custom, Kurt resolved to himself, and nerved himself to face the chill air and the cold stone floor, when he had planned a far warmer and more pleasant morning.

He joined Mim in the bath and she washed his back for him, making clouds of comfortable steam with the warm water, laughing and not at all caring that the water soaked her dressing gown.

She was content with him.

At times the warmth in her eyes or the lingering touch of her fingers said she was more than content.

The hardest thing that faced them was to go down the stairs into the rhmei,at which Mim actually trembled. Kurt took her arm and would have brought her down with his support, but the idea shocked her. She shook free of him and walked like a proper nemet lady, independently behind him down the stairs.

The guests and family met them at the foot of the steps and brought them into the rhmeiwith much laughter and with ribald jokes that Kurt would not have believed possible from the modest nemet. He was almost angry, but when Mim laughed he knew that it was proper, and forgave them.

After the round of greetings, Aimu came and served the morning tea, hot and sweet, and the elders sat in chairs while the younger people—Kurt and Mim included, and Hef, who was chan,—sat upon rugs on the floor and drank their tea and listened to the elders talk. Kta played one haunting song for them on the aos,without words, but just for listening and for being still.

Mim would be honored in the house and exempt from duties for the next few days, after which time she would again take her share with Ptas and Aimu; she sat now and accepted the attentions and the compliments and the good wishes,—Mim, who had never expected to be more than a minor concubine to the lord of Elas, accepted with private vows and scant legitimacy—now she was the center of everything.

It was her hour.

Kurt begrudged her none of it, even the nemet humor. He looked down at her and saw her face alight with pride and happiness—and love, which she would have given with lesser vows had he insisted; and he smiled back and pressed her hand, which the others kindly did not elect to make joke of at that moment.

10

Ten days passed before the outside world intruded again into the house of Elas.

It came in the person of Bel t’Osanef u Han, who arrived, escorted by Mim, in the garden at the rear of the house, where Kta was instructing Kurt in the art of the ypan,the narrow curved longsword that was the Indras’ favorite weapon and chief sport.

Kurt saw Bel come into the garden and turned his blade and held it in both hands to signal halt. Kta checked himself in mid-strike, and turned his head to see the reason of the pause. Then with the elaborate ritual that governed the friendly use of these edged weapons, Kta touched his left hand to his sword and bowed, which Kurt returned. The nemet believed such ritual was necessary to maintain balance of soul between friends who contended in sport, and distrusted the blades. In the houses of the Families resided the ypai-sulim,the Great Weapons which had been dedicated in awful ceremony to the house Guardians and bathed in blood. These were never drawn unless a man had determined to kill or to die, and could not be sheathed again until they had taken a life. Even these light foils must be handled carefully, lest the ever-watchful house spirits mistake someone’s intent and cause blood to be drawn.

And once it had been death to the Sufaki to touch these lesser weapons, or even to look at the ypai-sulimwhere they hung at rest, so that fencing was an art the Sufaki had never employed: they were skilled with the spear and the bow—distance-weapons.

Bel waited at a respectful distance until the weapons were safely sheathed and laid aside, and then came forward and bowed.

“My lords,” said Mim, “shall I bring tea?”

“Do so, Mim, please,” said Kta. “Bel, my soon-to-be brother—”

“Kta,” said Bel. “My business is somewhat urgent.”

“Sit then,” said Kta, puzzled. There were several stone benches about the garden. They took those nearest.

Then Aimu came from the house. She bowed modestly to her brother. “Bel,” she said then, “you come into Elas without at least sending me greetings? What is the matter?”

“Kta,” said Bel, “permission for your sister to sit with us.”

“Granted,” said Kta, a murmured formality, as thoughtless as “thank you.” Aimu sank down on the seat near them. There were no further words. Tea had been asked; Bel’s mood was distraught. There was no discussion proper until it had come, and it was not long. Mim brought it on a tray, a full service with extra cups.

Aimu rose up and helped her serve, and then both ladies settled on the same bench while the first several sips that courtesy demanded were drunk in silence and with appreciation.

“My friend Bel,” said Kta, when ritual was satisfied, “is it unhappiness or anger or need that has brought you to this house?”

“May the spirits of our houses be at peace,” said Bel. “I am here now because I trust you above all others save those born in Osanef. I am afraid there is going to be bloodshed in Nephane.”

“T’Tefur,” exclaimed Aimu with great bitterness.

“I beg you, Aimu, hear me to the end before you stop me.”

“We listen,” said Kta, “but, Bel, I suddenly fear this is a matter best discussed between our fathers.”

“Our fathers’ concern must be with Tlekef; Shan t’Tefur is beneath their notice—but he is the dangerous one, much more than Tlekef. Shan and I—we were friends. You know that. And you must realize how hard it is for me to come now to an Indras house and say what I am going to say. I am trusting you with my life.”

“Bel,” said Aimu in distress, “Elas will defend you.”

“She is right,” said Kta, “but Kurt—may not wish to hear this.”

Kurt gathered himself to leave: it was Bel’s willingness to have him stay that Kta questioned; he had been long enough in Elas to understand nemet subtleties. It was expected of Bel to demur.

“He must stay,” said Bel, with more feeling than courtesy demanded. “He is involved.”

Kurt settled down again, but Bel remained silent a time thereafter, staring fixedly at his own hands.

“Kta,” he said finally, “I must speak now as Sufaki. There was a time, you know, when we ruled this land from the rock of Nephane to the Tamur and inland to the heart of Chteftikan and east to the Gray Sea. Nothing can ever bring back those days; we realize that. You have taken from us our land, our gods, our language, our customs,—you accept us as brothers only when we look like you and talk like you, and you despise us for savages when we are different.—It is true, Kta: look at me. Here am I, born a prince of the Osanef, and I cut my hair and wear Indras robes and speak with the clear round tones of Indresul, like a good civilized man, and I am accepted. Shan is braver. He does what many of us would do if we did not find life so comfortable on your terms. But Elas taught him a lesson I did not learn.”

“He left us in anger. I have not forgotten the day. But you stayed.”

“I was eleven; Shan was twelve. At that time we thought it a great thing—to be friends to an Indras, to be asked beneath the roof of one of the Great Families, to mingle with the Indras. I had come many times; but this day I brought Shan with me, and Ian t’Ilev chanced to be your guest also that day. Ian made it clear enough that he thought our manners quaint. Shan left on the instant; you prevented me, and persuaded me to stay, for we were closer friends, and longer friends. And from that day Shan t’Tefur and I had in more than that sense gone our separate ways. I could not call him back. The next day when I met him I tried to convince him to go back to you and speak with you,—but he would not. He struck me in the face and cursed me from him, and said that Osanef was fit for nothing but to be servant to the Indras—he said it in cruder words—and that he would not. He has not ceased to despise me.”

“It was not well done,” said Kta. “I had bitter words with Ian over the matter, until he came to a better understanding of courtesy, and my father went to Ilev’s father. I assure you it was done. I did not tell you so; there never seemed a moment apt for it.”

“Kta,—if I had been Indras, would you have found a moment apt for it?”

Kta gave back a little, his face sobered and troubled. “Bel, if you were Indras, your father would have come to Elas in anger and I would have been dealt with by mine—most harshly. I did not think it mattered, since your customs are different. But times are changing. You will become marriage-kin to Elas. Can you doubt that you would have justice from us?”

“I do not question your friendship,” he said, and looked at Aimu. “Times change, when a Sufaki can marry an Indras, where once Sufaki were not admitted to an Indras rhmeiwhere they could meet the daughters of a Family. But there are still limitations, friend Kta. We try to be businessmen and we are constantly outmaneuvered and outbid by the combines of wealthy Indras houses; information passes from hearth to hearth along lines of communication we do not share. When we go to sea, we sail under Indras captains, as I do for you, my friend,—because we have not the wealth to maintain warships as a rule,—seldom ever merchantmen. A man like Shan, that makes himself different, who wears the jafikn,who wears the Robes of Color, who keeps his accent—you ridicule him with secret smiles, for what was once unquestioned honor to a man of our people. There is so little left to us of what we were. Do you know, Kta, after all these years,—that I am not really Sufaki? Is that a surprise to you? You have ruined us so completely that you do not even know our real name. The people of this coast are Sufaki, the ancient name of this province when we ruled it, but the house of Osanef and the house of Tefur are Chteftik, from the old capital. And my name, despite the way I have corrupted it to please Indras tongues, is not Bel t’Osanef u Han. It is Hanu Balaket Osanef, and nine hundred years ago we rivaled the Insu dynasty for power in Chteftikan. A thousand years ago, when you were struggling colonists, we were kings, and no man would dare approach us on his feet. Now I change my name to show I am civilized, and bear with you when your cultured accent mispronounces it. Kta, Kta, I am not bitter with you. I tell you these things so that you will understand, because I know that Elas is one Indras house who might listen. You Indras are not trusted. There is talk of some secret accommodation you may have made with your kinsmen of Indresul,—talk that all your vowing war is empty, that you only do this like fisherman at a market, to increase the price in your bargain with Indresul.”

“Now hold up on that point,” Kta broke in, and for the first time anger flashed in his eyes. “Since you have felt moved to honesty with me,—which I respect,—hear me, and I will return it. If Indresul attacks, we will fight. It has always been a fault in Sufaki reasoning that you assume Indresul loves us like its lost children; quite the contrary. We are yearly cursed in Indresul, by the very families you think we share. We share Ancestors up to a thousand years ago, but beyond that point we are two hearths, and two opposed sets of Ancestors, and we are Nephanite. By the very hearth-loyalty you fear so much, Nephanite, and by the light of heaven I swear to you there is no such conspiracy among the Families. We took your land, yes, and there were cruel laws, yes, but that is in the past, Bel. Would you have us abandon our ways and become Sufaki? We would die first. But I do not think we impose our ways on you. We do not force you to adopt our dress or to honor our customs save when you are under our roof. You yourselves give most honor to those who seem Indras. You hate each other too much to unite for trade as our great houses do. Shan t’Tefur himself admits that when he pleads with you to make companies and rival us for trade. By all means. It would improve the lot of your poor, who are a charge on us.”

“And why, Kta? You assume that we can rise to your level. But have you ever thought that we might not want to be like you?”

“Do you have another answer? Some urge it, like Shan,—to destroy all that is Indras. Will that solve matters?”

“No. We will never know what we might have been; our nation is gone, merged with yours. But I doubt we would like your ways, even if things were upside down and we were ruling you.”