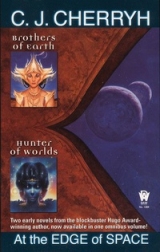

Текст книги "At the Edge of Space (Brothers of Worlds; Hunter of Worlds)"

Автор книги: C. J. Cherryh

Жанр:

Космическая фантастика

сообщить о нарушении

Текущая страница: 27 (всего у книги 36 страниц)

Aiela.Isande’s presence drew at him from the other side, worried. He struggled back toward it, felt the physical touch of her hand on his shoulder. The warmth of the paredreclosed about him again. Too long in contact,she sent him. Aiela, Aiela, think of here. Let go of him, let go.

“I am all right,” he insisted, pushing aside her fear. But she continued to look at him concernedly for a little time more before she accepted his word for it. Then she reached for the computer contact.

The paredredoor shot open, startling them both, and Mejakh’s angry presence stopped Isande’s hand in mid-move. The woman was brusque and rude and utterly tangible. Almost Isande called out to Chimele a frightened appeal, but Chimele looked up from her own desk a distance away and fixed Mejakh with a frown.

“You were not called,” Chimele said.

Mejakh swept a wide gesture toward Aiela and Isande. “Get them out. I have a thing to say to you, Chimele-Orithain, and it is not for the ears of m’metanei.”

“They are aiding me,” said Chimele, bending her head to resume her writing. “You are not. You may leave, Mejakh.”

“You are offended because I quit the meeting. But you had no answer when Kharxanen baited me. You enjoyed it.”

“Your incredible behavior left me little choice.” Chimele looked up in extreme displeasure as Mejakh in her argument came to the front of the desk. Chimele laid aside her pen and came up from her chair with a slow, smooth motion. “You are not noticed, Mejakh. Your presence is ignored, your words forgotten. Go.”

“ Ashanomehas no honor when it will not defend its own.”

Chimele’s head went back and her face was cold. “You are not of my s ra,Mejakh. Once you had honor and Chaxal was compelled to notice you, but in his wisdom he did not take you for kataberihe.You are a troublemaker, Mejakh. You threw away your honor when you let yourself be taken into Tashavodhby Tejef. There was the beginning of our present troubles; and what it has cost us to recover you to the nasulwas hardly worth it, o Mejakh, trouble-bringer.”

“You would not say so if Khasif were here to hear it.”

“For Khasif’s sake I have tolerated you. I am done.”

Mejakh struggled for breath. Could iduve have wept she might have done so. Instead she struck the desk top with a crash like an explosion. “Bring them all up! Bring up Khasif, yes, and this human nas kame, all of them! Wipe clean the surface of this world and be done! It is clear, Orithain, that you have more m’melakhiathan sorithias.It is your own vaikkayou pursue, a vaikkafor the insult he did you personally, not for the honor of Ashanome.”

Chimele came around the side of the desk and Isande’s thoughts went white with fear: Rakhi, get Rakhi in here,she flashed to Aiela, and reached for the desk intercom; Aiela launched himself toward the two iduve.

His knees went. Unbelievable pain shot up his arm to his chest and he was on his face on the floor, blood in his mouth, hearing Isande’s sobs only a few feet away. The pain was a dull throb now, but he could not reach Isande. His limbs could not function; he could not summon the strength to move.

After a dark moment Chimele bent beside him and lifted his head, urging him to move. “Up,” she said. “Up, kameth.”

He made the effort, hauled himself up by the side of a chair and levered himself into it, searching desperately with his thoughts for Isande. Her contact was active, faint, stunned, but she was all right. He looked about when his vision had cleared and saw her sitting in a chair, head in her hands, and Rakhi standing behind her.

“Both of them seem all right,” said Rakhi. “What instructions about Mejakh?”

“She is forbidden the paredre,” Chimele said, and looked toward her kamethi. “Mejakh willed your death, but I overrode the impulse. It is a sadness; she had arastietheonce, but her loss of it at Tejef’s hands has disturbed her reason and her sense of chanokhia.”

“She has had misfortune with her young,” said Rakhi. “Against one she seeks vaikka,and for his sake she lost her honor. Her third was taken from her by the Orithanhe. Only in Khasif has she honorable sra,and he is absent from her. Could it be, Chimele, that she is growing dhisais?”

“Make it clear to the dhis-guardians that she must not have access there. You are right. She may be conceiving an impulse in that direction, and with no child in the dhis,there is no predicting what she may do. Her temper is out of all normal bounds. She has been disturbed ever since the Orithanhe returned her to us without her child, and this long waiting with Priamos in view– au,it could happen. Isande, Aiela, I must consider that you are both in mortal danger. Your loss would disturb my plans; that would occur to her, and kamethi have no defense against her.”

“If we were armed—” Aiela began.

“ Au,” Chimele exclaimed, “no, m’metane,your attitude is quite understandable, but you hardly appreciate your limitations. You almost died a moment ago, have you not realized that? The idoikkheican kill. Chanokhiainsists kamethi are exempt from such extreme vaikka,but Mejakh’s sense of chanokhiaseems regrettably lacking.”

“But a dhisais,” Aiela objected, “can be years recovering.”

“Yes, and you see the difficulty your attempt to interfere has created. Well, we will untangle the matter somehow, and, I hope, without further vaikka.”

“Chimele,” said Rakhi, “the kameth has a valid point. Mejakh has proved an embarrassment many times in the matter of Tejef. Barring her from the paredremay not prove sufficient restraint.”

“Nevertheless,” said Chimele, “my decision stands.”

“The Orithain cannot make mistakes.”

“But even so,” Chimele observed, “I prefer to proceed toward infallibility at my own unhurried pace, Rakhi. Have you heard from Ashakh yet?”

“He acknowledged. He has left Priamos by now, and he will be here with all possible speed.”

“Good. Go back to your station. Aiela, Isande, if we are to salvage Daniel, you must find him a suitable unit and dispose of that child by some means. I trust you are still keeping your actions shielded from him. His mind is already burdened with too much knowledge. And when I do give you leave to contact him, you may tell him that I am ill pleased.”

“I have already made that clear to him.”

“She is not his,” Chimele objected, still worrying at that thought.

“She attached herself to him for protection. She became his.”

“There is no nasith-tak,no female, no katasathe,no dhisais.Is it reasonable that a male would do this, alone?”

“I am sure it is. An iduve would not?”

That was a presumptuous question. Isande reproved his asking, but Chimele lowered her eyes to show decent shame and then looked up at him.

“A female would be moved to do what he has done as if she were katasatheand near her time. A male could not, not without the presence of a female with whom he had recently mated. But is not this child-female close to adulthood? Perhaps it is the impulse to katasakkethat has taken him.”

“No,” said Aiela, “no, when he thinks of her, it is as a child. That—unworthy thought did cross his mind; he drove it away. He was deeply ashamed.”

He wished he had not said that private thing to Chimele. Had he not been so tired he would have withheld it. But it had given her much to ponder. Bewilderment sat in her eyes.

“She is chanokhiato him,” Aiela said further. “To him she is the whole human race. You and I would not think so, but to him she is infinitely beautiful.”

And he rejoined Isande at the desk, where with trembling hands she began to ply the keyboard again and to call forth the geography of Priamos on the viewer, marking it with the sites of occupied areas, receiving reports from the command center, updating the map. There were red zones for amaut occupation, green for human, and the white pinpricks that were iduve: one at Weissmouth in a red zone, that was Khasif; and one in the continental highlands a hundred lioifrom Daniel, which was Tejef at best reckoning.

When Aiela chanced at last to notice Chimele again she was standing by her desk in the front of the paredre,which had expanded to a dizzying perspective of Ashanome’s hangar deck, talking urgently with Ashakh.

It was fast coming up dawn in the Weiss valley. The divergent rhythms of ship and planetary daylight systems were not least among the things that had kept Aiela’s mind off-balance for fifteen days. He thought surely that Daniel would have been compelled by exhaustion to lie down and sleep. He could not possibly have the strength to go much further. But even wondering about Daniel could let information through the screening. Aiela turned his mind away toward the task at hand, sealing against any further contact.

The light was beginning to rise, chasing Priamos’ belt of stars from the sky, and by now Daniel’s steps wandered. Oftentimes he would stop and stare down the long still-descending road, dazed. Aiela’s thoughts were silent in him. He had felt one terrible pain, and then a long silence, so that he had forgotten the importance of his rebellion against Aiela and hurled anxious inquiry at him, whether he were well, what had happened. The silence continued, only an occasional communication of desperation seeping through. It was Chimele’s doing, then, vaikkaagainst Aiela, thoroughly iduve, but against him, against all Priamos, her retaliation would not be so slight.

In cold daylight Daniel knew what he had done, that a world might die because he had not had the stomach to commit one more murder; but he refused steadfastly to think that far ahead, or to believe that even Chimele could carry out a threat so brutally—that he and the little girl would become only two among a million corpses to litter the surface of a dead world.

His ankle turned. He caught himself and the child’s thin arms tightened about his neck. “Please,” she said. “Let me try to walk again.”

His legs and shoulders and back were almost numb, and the absence of her weight was inexpressible relief. Now that the light had come she looked pitifully naked in her thin yellow gown, very small, very dislocated, walking this wilderness all dressed for bed, as if she were the victim of a nightmare that had failed to go away with the dawn. At times she looked as if she feared him most of all, and he could not blame her for that. That same dawn showed her a disreputable man, face stubbled with beard, a man who carried an ugly black gun and an assassin’s gear that must be strange indeed to the eyes of the country child. If her parents had ever warned her of rough men, or men in general—was she old enough to understand such things?—he conformed to every description of what to avoid. He wished that he could assure her he was not to be feared, but he thought that he would stumble hopelessly over any assurances that he might try to give her, and perhaps might frighten her the more.

“What’s your name?” she asked him for the first time.

“Daniel Fitzhugh,” he said. “I come from Konig.”

That was close enough she would have heard of it, and the mention of familiar places seemed to reassure her. “My name is Arle Mar,” she said, and added tremulously: “That was my mother and father’s farm.”

“How old are you?” He wanted to guide the questioning away from recent memory. “Twelve?”

“Ten.” Her nether lip quivered. “I don’t want to go this way. Please take me back home.”

“You know better than that.”

“They might have gotten away.” He thought she must have treasured that hope a long time before she brought it out into the daylight. “Maybe they hid like I did and they’ll be looking for me to come back.”

“No chance. I’m telling you—no.”

She wiped back the tears. “Have you got an idea where we should go? We ought to call the Patrol, find a radio at some house—”

“There’s no more law on Priamos—no soldiers, no police, nothing. We’re all there is—men like me.”

She looked as if she were about to be sick, as if finally all of it had caught up with her. Her face was white and she stood still in the middle of the road looking as if she might faint.

“I’ll carry you,” he offered, about to do so.

“ No!” If her size had been equal to her anger she would have been fearsome. As it was she simply plumped down in the middle of the road and rested her elbows on her knees and her face in her hands. He did not press her further. He sat down cross-legged not far away and rested, fingers laced on the back of his neck, waiting, allowing her the dignity of gathering her courage again. He wanted to touch her, to hug her and let her cry and make her feel protected. He could not make the move. A human could touch, he thought; but he was no longer wholly human. Perhaps she could feel the strangeness in him; if that were so, he did not want to learn it.

Finally she wiped her eyes a last time, arose stiffly, and delicately lifted the hem of her tattered nightgown to examine her skinned knees.

“It looks sore,” he offered. He gathered himself to his feet.

“It’s all right.” She let fall the hem and gave the choked end of a sob, wiping at her eyes as she surveyed the valley that lay before them in the sun, the gently winding Weiss, the black and burned fields. “All this used to be green,” she said.

“Yes,” he said, accepting the implied blame.

She looked up at him, squinting against the sun. “Why?” she asked with terrible simplicity. “Why did you need to do that?”

He shrugged. It was beyond his capacity to explain. The truth led worse places than a lie. Instead he offered her his hand. “Come on. We’ve got a long way to walk.”

She ignored his hand and walked ahead of him. The road was soft and sandy with a grassy center, and she kept to the sand; but the sun heated the ground, and by the time they had descended to the Weiss plain the child was walking on the edges of her feet and wincing.

“Come on,” he said, picking her up willing or not with a sweep of his arm behind her knees. “Maybe I—”

He stopped, hearing a sound very far away, a droning totally unlike the occasional hum of the insects. Arle heard it too and followed his gaze, scanning the blue-white sky for some sign of an aircraft. It passed, a high gleam of light, then circled at the end of the vast plain and came back.

“All right,” he said, keeping his voice casual. Aiela, Aiela, please hear me.“That’s trouble. If they land, Arle, I want you to dive for the high weeds and get down in that ditch.” Aiela! give me some help!

“Who are they?” Arle asked.

“Probably friends of mine. Amaut, maybe. Remember, I worked for the other side. I may be picked up as a deserter. You may see some things you won’t like.” O heaven, Aiela, Aiela, listen to me!“I can lie my way out of my own troubles. You, I can’t explain. They’ll skin me alive if they see you, so do me a favor: take care of your own self, whatever you see happen, and stay absolutely still. You can’t do a thing but make matters worse for me, and they have sensors that can find you in a minute if they choose to use them. Once they suspect I’m not alone, you haven’t got a chance to hide from them. You understand me? Stay flat to the ground.”

It was coming lower. Engines beating, it settled, a great silver elongated disc that was of no human make. A jet noise started as they whined to a landing athwart the road, and the sand kicked up in a blinding cloud. Under its cover Daniel set Arle down and trusted her to run, turned his face away and flung up his arms to shield his eyes from the sand until the engines had died away to a lazy throb. The ship shone blinding bright in the sun. A darkness broke its surface, a hatch opened and a ramp touched the ground.

Aiela!Daniel screamed inwardly; and this time there was an answer, a quick probe, an apology.

Amaut,Daniel answered, and cast him the whole picture in an eyeblink, the ship, the amaut on the ramp, the humans descending after. Parker: Anderson’s second in command.Daniel cast in bursts and snatches, abjectly pleading with his asuthe, forgive his insubordination, tell Chimele, promise her anything, do something.

Aiela was doing that; Daniel realized it, was subconsciously aware of the kallia’s fright and Chimele’s rage. It cut away at his courage. He sweated, his hand impelled toward the gun at his hip, his brain telling it no.

Parker stepped off the end of the ramp, joined by two more of the ugly, waddling amaut, and by another mercenary, Quinn.

“Far afield, aren’t you?” Parker asked of him. It was not friendliness.

“I got separated last night, didn’t have any supplies. I decided to hike back riverward, maybe pick up with some other unit. I didn’t think I rated that much excitement from the captain.” It was the best and only lie he could think of under the circumstances. Parker did not believe any of it, and spat expressively into the dust at his feet.

“Search the area,” the amaut said to his fellows. “We had a double reading. There’s another one.”

Daniel went for his pistol. No!Aiela ordered, throwing him off-time, making the movement clumsy.

The amaut fired first. The shot took his left leg from under him and pitched him onto his face in the sand. Arle’s thin scream sounded in his ears—the wrist of his right hand was ground under a booted heel and he lost his gun, had it torn from his fingers. Aiela, driven back by the pain, was trying to hold onto him, babbling nonsense. Daniel could only see sideways– Arle, struggling in the grip of the other human, kicking and crying. He was hurting her.

Daniel lurched for his feet, screamed hoarsely as a streak of fire hit him in the other leg. When he collapsed writhing on the sand Parker set his foot on his wrist and took deliberate aim at his right arm. The shot hit. Aiela left him, every hope of help left him.

Methodically, as if it were some absorbing problem, Parker took aim for the other arm. The amaut stood by in a group, curiosity on their broad faces. Arle’s shrill scream made Parker’s hand jerk.

“No!” Daniel cried to the amaut, and he had spoken the kalliran word, broken cover. The shot hit.

But the amaut’s interest was pricked. He pulled Parker’s arm down; and no loyalty to the ruthless iduve was worth preserving cover all the way to a miserable death. Daniel gathered his breath and poured forth a stream of oaths, native and kalliran, until he saw the mottled face darken in anger. Then he looked the amaut straight in his froggish eyes, conscious of the fear and anger at war there.

“I am in the service of the iduve,” he said, and repeated it in the iduve language should the amaut have any doubt of it. “You lay another hand on me or her and there will be cinders where your ship was, and you know it, you gray horror.”

“ Hhhunghh.” It was a grunt no human throat could have made. And then he spoke to Parker and Quinn in human language. “No. We take thiss—thiss.” He indicated first Daniel and then Arle. “You, you, walk, report Anderson. Go. Goodbye.”

He was turning the two mercenaries out to walk to their camp. Daniel felt a satisfaction for that which warmed even through the pain: Vaikka?he thought, wondering if it were human to be pleased at that. A hazy bit of yellow hovered near him, and he felt Arle’s small dusty hand on his cheek. The remembrance of her among the amaut brought a fresh effort from him. He tried to think.

Daniel.Aiela’s voice was back, cold, efficient, comforting. Convince them to take you to Weissmouth. Admit you serve the iduve there; that’s all you can do now.Chimele was furious. That leaked through, frightening in its implications. The screen went up again.

“That ship overhead,” Daniel began, eyeing the amaut, drunk with pain, “there’s no place on this world you can hide from that. They have their eye on you this instant.”

The other amaut looked up as if they expected to see destruction raining down on them any second; but the captain rolled his thin lips inward, the amaut method of moistening them, like a human licking his lips.

“We are small folk,” he said, mouth popping on all the explosive consonants, but he spoke the kalliran language with a fair fluency. “One iduve-lord we know. One only we serve. There is safety for us only in being consistent.”

“Listen, you—listen! They’ll destroy this world under you. Get me to the port at Weissmouth. That’s your chance to live.”

“No. And I have finished talking. See to him,” he instructed his subordinates as he began to walk toward the ramp, speaking now in the harsh amaut language. “He must live until the lord in the high plains can question him. The female too.”

“He had no choice,” said Aiela.

Chimele kept her back turned, her arms folded before her. The idoikkhetingled spasmodically. When she faced him again the tingling had stopped and her whiteless eyes stared at him with some degree of calm. Aiela hurt; even now he hurt, muscles of his limbs sensitive with remembered pain, stomach heaving with shock. Curiously the only thing clear in his mind was that he must not be sick: Chimele would be outraged. He had to sit down. He did so uninvited.

“Is he still unconscious?”

Chimele’s breathing was rapid again, her lip trembling, not the nether lip as a kalliran reaction would have it: Attack!his subconscious read it; but this was Chimele, and she was civilized and to the limit of her capacity she cared for her kamethi. He did not let himself flinch.

“We have a problem,” she said by way of understatement, and hissed softly and sank into the chair behind her desk. “Is the pain leaving?”

“Yes.” Isande—Isande!

His asuthe stood behind him, took his hand, seized upon his mind as well, comforting, interfering between memory and reality. Be still,she told him, be still. I will not let go.

“Could you not have prevented him talking?” Chimele asked.

“He was beyond reason,” Aiela insisted. “He only reacted. He thought he was lost to us.”

“And duty. Where was that?”

“He thought of the child, that she would be alone with them. And he believed you would intervene for him if only he could survive long enough.”

“The m’metanehas an extraordinary confidence in his own value.”

“It was not a conscious choice.”

“Explain.”

“Among his kind, life is valued above everything. I know, I know your objections, but grant me for a moment that this is so. It was a confidence so deep he didn’t think it, that if he served beings of arastiethe,they would consider saving his life and the child’s of more value than taking that of Tejef.”

“He is demented,” Chimele said.

Careful,Isande whispered into his mind. Soft, be careful.

“You gave me a human asuthe,” Aiela persisted, “and told me to learn his mind. I’m kallia. I believe kastienis more important than life—but Daniel served you to the limit of his moral endurance.”

“Then he is of no further use,” said Chimele. “I shall have to take steps of my own.”

His heart lurched. “You’ll kill him.”

Chimele sat back, lifted her brows at this protest from her kameth, but her hand paused at the console. “Do you care to stay asuthithekkhewith him while he is questioned by Tejef? Do not be distressed. It will be sudden; but those who harmed him and interfered with Ashanomewill wish they had been stillborn.”

“If you can intervene to kill him, you can intervene to save him.”

“To what purpose?”

Aiela swallowed hard, screened against Isande’s interference. He sweated; the idoikkhehad taught its lesson. “It is not chanokhiato destroy him, any more than it was to use him as you did.”

The pain did not come. Chimele stared into the trembling heart of him. “Are you saying that I have erred?”

“Yes.”

“To correctly assess his abilities was your burden. To assign him was mine. His misuse has no relevance to the fact that his destruction is proper now. Your misguided giyrewill cost him needless pain and lessen the arastietheof Ashanome.If he comes living into the hands of Tejef he may well ask you why you did not let him die; and every moment we delay, intervention becomes that much more difficult.”

“He is kameth. He has that protection. It would not be honorable for Tejef to harm him.”

“Tejef is arrhei-nasuli,an outcast. It would not be wise to assume he will be observant of nasul-chanokhia.He is not so bound, nor am I with him. He may well choose to harm him. We are wasting time.”

“Then contact that amaut aircraft and demand Daniel and the child.”

“To what purpose?”

The question disarmed him. He snatched at some logic the iduve might recognize. “He is not useless.”

“How not? Secrecy is impossible now. Tejef will be alerted to the fact that I have a human nas kame; besides, the amaut in the aircraft would probably refuse my order. Tejef is their lord; they said so quite plainly, and amaut are nothing if not consistent. To demand and to be refused would mean that we had suffered vaikka,and I would still have to destroy a kameth of mine, having gained nothing. To risk this to save what I am bound to lose seems a pointless exercise; the odds are too high. I am not sure what you expect of me.”

“Bring him back to Ashanome.Surely you have the power to do it.”

“There is no longer time to consider that alternative. Shall I commit more personnel at Tejef s boundaries? The risk involved is not reasonable.”

“No!” Aiela cried as she started to turn from him. He rose from his chair and leaned upon her desk, and Chimele looked up at him with that bland patience swiftly evaporating.

“What are you going to do with Priamos when you’ve destroyed him?” Aiela asked. “With three days left, what are you going to do? Blast it to cinders?”

“Contrary to myth, such actions are not pleasurable to us. I perceive you have suffered extreme stress in my service and I have extended you a great deal of patience, Aiela; I also realize you are trying to give me the benefit of our knowledge. But there will be a limit to my patience. Does your experience suggest a solution?”

“Call on Tejef to surrender.”

Chimele gave a startled laugh. “Perhaps I shall. He would be outraged. But there is no time for a m’metane’shumor. Give me something workable. Quickly.”

“Let me keep working with Daniel. You wanted him within reach of Tejef. Now he is, and whatever else, Tejef has no hold over him with the idoikkhe.”

“You m’metaneiare fragile people. I know that you have giyreto your asuthe, but to whose advantage is this? Surely not to his.”

“Give me something to bargain with. Daniel will fight if he has something to fight for. Let me assure him you’ll get the amaut off Priamos and give it back to his people. That’s what he wants of you.”

Chimele leaned back once more and hissed softly. “Am I at disadvantage, to need to bargain with this insolent creature?”

“He is human. Deal with him as he understands. Is that not reasonable? Giyreis nothing to him; he doesn’t understand arastiethe.Only one thing makes a difference to him: convince him you care what—”

A probing touch found his consciousness and his stomach turned over at foreknowledge of the pain. He tried to screen against it, but his sympathy made him vulnerable.

“Daniel is conscious.” Isande spoke, for at the moment he had not yet measured the extent of the pain and his mind was busy with that. “He is hearing the amaut talk. The child Arle is beside him. He is concerned for her.”

“Dispense with his concern for her. Tell him you want a report.”

Aiela tried. Tears welled in his eyes, an excess of misery and weariness; the pain of the wounds blurred his senses. Daniel was half-conscious, sending nonsense, babble mixed with vague impressions of his surroundings. He was back on the amaut freighter. There was wire all about. Aiela, Aiela, Aiela,the single thread of consciousness ran, begging help.

I’m here,he sent furiously. So is Chimele. Report.

“‘I,’” Aiela heard and said aloud for Chimele, “ ‘I’m afraid I have—penetrated Tejef’s defenses—in a somewhat different way than she had planned. We’re coming down, I think. Stay with me—please, stay with me, if you can stand it. I’ll send you what I—what I can learn.’ ”

“And he will tell Tejef what Tejef asks, and promise him anything. A creature that so values his own life is dangerous.” Chimele laced her fingers and stared at the backs of them as if she had forgotten the kamethi or dismissed the problem for another. Then she looked up. “ Vaikka.Tejef has won a small victory. I have regarded your arguments. Now I cannot intervene without using Ashanome’s heavy armament to pierce his defenses—a quick death to Tejef, ruin to Priamos, and damage to my honor. This is a bitterness to me.”

“Daniel still has resources left,” Aiela insisted. “I can advise him.”

“You are not being reasonable. You are fatigued: your limbs shake, your voice is not natural. Your judgment is becoming highly suspect. I have indeed erred to listen to you.” Chimele gathered the now-useless position report together and put it aside, pushed a button on the desk console, and frowned. “Ashakh: come to the paredreat once. Rakhi: contact Ghiavre is the lab and have him prepare to receive two kamethi for enforced rest.”

Rakhi acknowledged instantly, to Aiela’s intense dismay. He leaned upon the desk, holding himself up. “No,” he said, “no, I am not going to accept this.”

Chimele pressed her lips together. “If you were rational, you would recognize that you are exceeding your limit in several regards. Since you are not—”

“Send me down to Priamos, if you’re afraid I’ll leak information to Daniel. Set me out down there. I’ll take my chances with the deadline.”

Chimele considered, looked him up and down, estimating. “Break contact with Daniel,” she said. “Shut him out completely.”

He did so. The effort it needed was a great one. Daniel screamed into the back of his mind, his distrust of Chimele finding echo in Aiela’s own thoughts.

“Very well, you may have your chance,” said Chimele. “But you will sleep first, and you will be transported to Priamos under sedation—both of you. Isande is likewise a risk now.”

He opened his mouth again to protest: but Isande’s strong will otherwise silenced him. She was afraid, but she was willing to do this for him. No harm will come to us,she insisted. Chimele will not permit it. Kallia can hardly operate in secrecy on a human world, so we shall go underAshanome’ s protection. Besides, you have already pressed her to the limit of her patience.