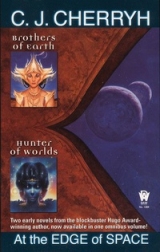

Текст книги "At the Edge of Space (Brothers of Worlds; Hunter of Worlds)"

Автор книги: C. J. Cherryh

Жанр:

Космическая фантастика

сообщить о нарушении

Текущая страница: 28 (всего у книги 36 страниц)

He silently acknowledged the force of that argument, and to Chimele he bowed in respect. “Thank you,” he said, meaning it.

Chimele waved a hand in dismissal. “I know this kalliran insanity of joy in being disadvantaged. But it would be improper to let you assume I do this solely to give you pleasure. Do not begin to act rashly or carelessly, as if I were freeing you of bond to Ashanomeor responsibility to me. Be circumspect. Maintain our honor.”

“Will we receive orders from you?”

“No.” Again her violet nail touched the button, this time forcefully, “Ashakh! Wherever you are, acknowledge and report to the paredreat once.” She was becoming annoyed; and for Ashakh to be dilatory in a response was not usual.

The door from the corridor opened and Ashakh joined them; he closed the door manually, and looked to have been running.

“There was a problem,” he said, when Chimele’s expression commanded an explanation. “Mejakh is in an argumentative mood.”

“Indeed.”

“Rakhi has now made it clear to her that she is also barred from the control center. What was it you wanted of me?”

“Take Aiela and Isande to their quarters and let them collect what they need for their comfort on Priamos. Then escort them to the lab; I will give Ghiavre his instructions while you are at that. Then arrange their transport down to Priamos; and it would not be amiss to provide them arms.”

“I have my own weapon,” said Aiela, “if I have your leave to collect it from storage.”

“Armament can provide you one more effective, I am sure.”

“I am kallia. I’m afraid if I had a lethal weapon in my hands I couldn’t fire it. Give me my own. Otherwise I can’t defend myself as I may need to.”

“Your logic is peculiar to your people, I know, but I perceive your reasoning. Take it, then. And as for instruction, kamethi—I provide you none. I am sure your knowledge of Priamos and of Daniel is thorough, and I trust you to remember your responsibility to Ashanome.One thing I forbid you: do not go to Khasif and do not expect him to compromise himself to aid you. You are dismissed.”

Aiela bowed a final thanks, waited for Isande, and walked as steadily as he could after Ashakh. Isande held his arm. Her mind tried to occupy his, washing it clean of the pain and the weakness. He forbade that furiously, for it hurt her as well.

In his other consciousness he was being handled roughly down a ramp, provided a dizzying view of a daylit sky: he dreaded to think what could happen to Daniel while he was helpless to advise him, and he imagined what Daniel must think, abandoned as he had been without explanation. We’ll be there,Aiela sent, defying orders; hold on, we’re coming;but Daniel was fainting. He stumbled, and Isande hauled up against him with all her strength.

“Ashakh!”

The tall iduve stopped abruptly at the corridor intersection a pace ahead of them and roughly shoved them back. Mejakh confronted them, disheveled and with a look of wildness in her eyes.

“They are killing me!” she cried hoarsely and lurched at Ashakh. “O nas,they are killing me—”

“Put yourself to order, nasith,” said Ashakh coldly, thrusting off her hands. “There are witnesses.”

Mejakh’s violet eyes rolled aside to Aiela and back again, showing whites at the corners, her lips parted upon her serrate teeth. “What is Chimele up to?” she demanded. “What insanity is she plotting, that she keeps me from controls? Why will no one realize what she is doing to the nasul? O nas,do you not see why she has sent Khasif away? She has attacked me; Khasif is gone. And you have opposed her—do you not see? All that dispute her—all that protest against her intentions—die.”

“Get back,” Ashakh hissed, barring the corridor to her with his arm.

Aiela felt the idoikkheand doubled; but Ashakh’s will held that off too, and he shouted at the both of them to run for their lives.

Aiela stumbled aside, Isande’s hand in his, Mejakh’s harsh voice pursuing them. He saw only closed doors ahead, a monitor panel at the corner such as there was at every turning. He reached it and hit the emergency button.

“Security!” he cried, dispensing with location: the board told them that. “Mejakh—!”

Through Isande’s backturned eyes he saw Ashakh recoil in surprise as Mejakh threatened him with a pistol. It burned the wall where Ashakh had been and had he not gone sprawling he would have been a dead man. His control of the idoikkheifaltered. Isande’s scream was half Aiela’s.

The weapon in Mejakh’s hand swung left, drawn from Ashakh by the sound. Down!Aiela shrieked at Isande and they separated by mutual impulse, low. The smell of scorched plastics and ozone attended the shot that missed them.

Ashakh heaved upward, hit Mejakh with his shoulder, sending her into the back wall of the corridor with a thunderous crash; but she did not fall, and locked in a struggle with him, he seeking to wrest the gun from her hand, she seeking to use it. Aiela scrambled across the intervening distance, Isande’s mind wailing terror into his, telling him it was suicide; but Ashakh maintained a tight hold on the idoikkheinow so that Mejakh could not send. Aiela seized Mejakh’s other arm to keep her from using her hand on Ashakh’s throat.

It was like grappling with a machine. Muscles like steel cables dragged irresistibly away from his grip, and when he persisted she struck at him, denting the wall instead and hurting her hand. She swung Ashakh into the way, trying to batter them both against the wall, and Aiela realized to his horror that Isande had thrown herself into the struggle too, trying vainly to distract Mejakh.

Suddenly Mejakh ceased fighting, and so did Ashakh. About them had gathered a number of iduve, male and female, a dhisaisin her red robes, three dhis-guardians in their scarlet-bordered black and bearing their antique ghiakai.Mejakh disengaged, backed from them. Ashakh with offended dignity straightened his torn clothing and turned upon her a deliberate stare. It was all that any of them did.

The door of the paredreopened at the other end of the corridor and Chimele was with them. Mejakh had been going in that direction. Now she stopped. She seemed almost to shrink in stature. Her movements hesitated in one direction and the other.

Then with a hiss rising to a shriek she whirled upon Ashakh. The ghiakaiof the dhis-guardians whispered from their sheaths, and Aiela seized Isande and pulled her as flat against the wall as they could get, for they were between Mejakh and the others. From the dhisaiscame a strange keening, a moan that stirred the hair at the napes of their necks.

“Mejakh,” said Chimele, causing her to turn. For a moment there was absolute silence. Then Mejakh crumpled into a knot of limbs, her two arms locked across her face. She began to sway and to moan as if is pain.

The others started forward. Chimele hissed a strong negative, and they paused.

“You have chosen,” said Chimele to Mejakh.

Mejakh twisted her body aside, gathered herself so that her back was to them, and began to retreat. The retreat became a sidling as she passed the others. Then she ran a few paces, bent over, pausing to look back. There was a terrible stillness in the ship, only Mejakh’s footsteps hurrying more and more quickly, racing away into distant silence.

The others waited still in great solemnity. Ashakh took Aiela and Isande each by an arm and escorted them back to Chimele.

“Are you injured?” Chimele asked in a cold voice.

“No,” said Aiela, finding it difficult to speak in all that silence. He could scarcely hear his own voice. Isande’s contact was almost imperceptible.

“Then pass from this hall as quickly as you may. Do you not see the dhisais?You are in mortal danger. Keep by Ashakh’s side and walk out of here very quietly.”

8

It was done at last. From his vantage point behind the glass Tejef watched the human grow still under the anesthetic and trusted him to the workmanlike mercies of the amaut physician—not an auspicious prospect if the wounds were much worse, if there were shattered joints or pieces missing. Then it would need the artistry of an iduve of the Physicians’ order. Tejef himself had only a passing acquaintance with the apparatus that equipped his ship’s surgery, a patch-and-hope adequacy that had been able to save a few human lives on Priamos. He had not sought them out, of course, but occasionally the okkitani-asbrought them in, and a few rash humans had actually come begging asylum, desperate and thirsty in the grasslands that surrounded the ship. Most injured that Tejef had treated lived, and acknowledged themselves mortally disadvantaged, and, in the curious custom of their kind, bound themselves earnestly to serve him. He was proud of this. He had gathered twenty-three humans in this way. They were not kamethi in the usual sense, for he had no access to chiabresor idoikkhei;still he reasoned that their service gave him a certain arastiethe,and although it was improper to hold m’metaneiby no honorable bond of loyalty, but only their own acknowledged disadvantage, that was the way of these beings, and he accepted the offering. He had also a hundred of the amaut attending him as okkitani-as,and had others dispersed into every center of amaut authority on Priamos. The amaut knew indeed that there was an iduve among them and they took him into account when they made their plans. In fact, he had directly applied pressure on their high command to give him this surgeon, for it was not proper that he practice publicly what was to him only an amateurish skill. He had been of the order of Science, and although it was his doom to perish world-bound, he still had some pride left in his order, not to soil his hands with work inexpertly done.

As his glance swept the small surgery his attention came again to the small yellow person who had defended the man so bravely. He remembered her hovering on this side and on that of the wounded man as he was borne across the field to the ship, darting one way and the other among the irritated amaut to keep sight of him while they brought him in, actually attacking one—a mottled, thick-necked fellow—who tried to keep her out of the surgery. She had gone for him with her teeth, that being all she had for weapons, and being batted aside, she darted under his reach and ensconced herself on a cabinet top in the corner, defying them all. Tejef had laughed to see it, although he laughed but seldom these days.

Now the wretched little creature sat watching the surgeon work, her face gone a sickly color even for a human. Her hand clutched her rag of a garment to her flat chest; her feet and knees were bloody and incredibly filthy—by no means proper for the surgery. She had not stopped fighting. She fairly bristled each time one of the amaut came near her in his ministrations, and then her eyes would dart again mistrustfully to see what the surgeon was doing with the man.

Tejef opened the door, signed the amaut not to notice him. Her eyes took him in too, seeming to debate whether he needed to be fought also.

“It’s all right,” he told her, exercising his scant command of her language. She looked at him doubtfully, then unwound her thin legs and came off the countertop, her lips trembling. When he beckoned her she ran to him, and to his dismay she flung her thin dirty arms about him and pressed her damp face against his ribs: he recoiled slightly, ashamed to be so treated before the amaut, who wisely pretended not to notice. The child poured at him a veritable flood of words, much more rapidly than he could comprehend, but she seemed by her actions to expect his protection.

“Much slower,” he said. “I can’t understand you.”

“Will he be all right?” she asked of him. “Please, please help us.”

Perhaps, he thought, it was because there was a certain physical similarity between iduve and human: perhaps to her desperate need he looked to be of her kind. He had schooled himself to a certain patience with humans. She was very young and it was doubtless a great shock to her to be hurled out of the security of the dhisinto this frightening profusion of faces and events. Even young iduve had been known to behave with less chanokhia.

“Hush,” he said, setting her back and making her straighten her shoulders. “They make him live. You—come with me.”

“No. I don’t want to.”

His hand moved to strike; he would have done so had a youngish iduve been insubordinate. But the shock and incomprehension on her face stopped him, and he quickly disguised the gesture, twice embarrassed before the okkitani-as.Instead he seized her arm—carefully, for m’metaneiwere inclined to fragility and she was as insubstantial as a stem of grass. He marched her irresistibly from the infirmary and down the corridor.

A human attendant was just outside the section. The child looked up at the being of her own species in tearful appeal, but she made no attempt to flee to him.

“Call Margaret to the dhis,” Tejef ordered the man, and continued on his way, slowing his step when he realized how the child was having to hurry to keep up with him.

“Where are we going?” she asked him.

“I will find proper—a proper—place for you. What is your name, m’metane?”

“Arle. Please let go my arm. I’ll come.”

He did so, giving her a little nod of approval. “Arle. I am Tejef. Who is your companion? Is he—a relative?”

“No.” She shook her head violently. “But he’s my friend. I want him to be all right—please—I don’t want him to be alone with them.”

“With the amaut? He is safe. Friend:I understand this idea. I have learned it.”

“What are you?” she asked him plainly. “And what are the amaut and why did they treat Daniel like that?”

The questions were overwhelming. He struggled to think in her language and abandoned the effort. “I am iduve,” he said. “Ask your kind. I don’t know enough words.” He paused at the entrance of the lift and set his hand on her shoulder, causing her to look up. It was a fine face, an impossibly delicate body. A creature of air and light, he thought in his own language, and rejected it as an expression more appropriate to Chaikhe than to one of his order. As an iduve this little creature would scarcely have survived the dhis,where the strength to take meant the right to eat and a nasof small stature or nameless birth needed extraordinary wit and will to live. He had survived despite the active persecution of the dhisaiseiand of Mejakh, and he had done so by a determination out of proportion to his origins. He prized such a trait wherever he found it.

“Are you going to help us?” she asked him.

He took her into the lift and started it moving downward.

“You are mine, you, your friend. You must obey and I must take care for you. You stand straight, have no fear for amaut or human. I take care for you.” The door opened and let them out on the level of what had been the dhis,sealed and dark until now.

There was Margaret, whom he had not seen in two days. He did not smile at her, being put off by her instant attachment to the child, for she exclaimed aloud and opened her arms to the child, petting her and making much of her with all the protective tenderness of a dhisaistoward young.

In some measure Tejef was relieved, for he had not been sure how Margaret would react. In another way he was troubled, for her accepting the child made her inappropriate as a mate and made final a parting he still was not sure he wanted. Margaret was the most handsome of the human females, with a glorious mane of fire-colored hair that made her at once the most alien and the most attractive. He had taken her many times in katasukke,but she troubled him by her insistence on touching him when they were not alone, and in her display of feelings when they were. She had wept when he admitted at last at great disadvantage that he did not understand the emotions of her kind in this regard, and did not know what she expected of him. He had been compelled to dismiss her from the khara-dhisafter that, troubled by the heat and violence she evoked in him, by the emotions she expected of him. She certainly could not hold her own if he forgot himself and treated her as nas.He would surely kill her, and when he came to himself he would regret it bitterly, for her irritating concern was well-meant, and he had a deep regard for her, almost as if she were indeed one of his own kind. That was the closest he dared come to what she wanted of him.

“Margaret,” he said with great dignity, “she is Arle.”

“The poor child.” She had her arms about the bedraggled girl and petted her solicitously. “How did she come here?”

“Ask her. I want to know. She is a child, yes? No?”

“Yes.”

He looked upon the pair of them, women that had been his first mate and this immature being of her own species, and was deeply disturbed. He knew it was very wrong to have brought this pale creature to the dhisinstead of assigning her among the kamethi, but now that it was done it was good to know that the dhisheld at least one life, and that Margaret, whom he must put away, had the child he could not give her. It was an honorable solution for Margaret. It was hard to give her up. Desire still stirred in him when he looked at her, nor could she understand why he suddenly rejected her. Hurt pleaded with him out of her eyes.

“She is yours,” he told her. “I give her. You will transfer your belongings here. She is your responsibility—yes?”

“All right,” she said.

He turned away abruptly, not to be troubled more by the harachiaof them. He knew that the door opened and closed, that the dhis,where no male and no nas kame or amaut might ever go, had been possessed by humans at his own bidding. He was ashamed of what he had done, but it was done now, and a strange furtive elation overrode the sense of shame. He had acquired a certain small vaikka,not alone in the disadvantaging of Chimele, but in the acquisition of the arastietheshe had decided to take from him. The dhisthat had remained dark and desolate now held light, life, and takei—females; his little ship had a comfort for him now it had lacked before those lights went on and that door sealed.

The sensible part of him insisted that he had plumbed the depths of disgrace in letting this happen; but those who decreed the traditions of honor could not understand the loneliness of an arrhei-nasuliand the sweetness there was in knowing he had worth in the sight of his kamethi. It lightened his spirit, and he told himself knowingly a great lie: that he had arastietheand a takkhenoisadequate to all events. He clutched to himself what he knew was a greater lie: that he might yet outwit Ashanomeand live. Like a gust of wind he stepped from the lift, grinned cheerfully at some of his startled kamethi and went on to the paredre.There were plans to make, resources to inventory.

“My lord.” Halph, assistant to the surgeon, came waddling after, operating gown and all. He bobbed his head many times in nervous respect.

“Report, Halph.”

“The chiabresis indeed present, lord Tejef. The honorable surgeon Dlechish will attempt to remove it if you wish, but removing it intact is beyond his knowledge.”

“No,” he said, for the human prisoner would be irreparably damaged by amaut probing at the chiabresif he allowed it. The human was a danger, but properly used, he could be of advantage. Kameth though he was, Chimele had most likely intended him as a spy or an assassin: against an arrhei-nasulithe neutrality of kamethi did not apply, and Chimele was not one to ignore an opportunity; the intricacy of the attempt against him that had failed delighted him. “You have not exposed it, have you?”

“No, no, my lord. We would not presume.”

“Of course. You are always very conscientious to consult me. Go back to Dlechish and tell him to leave the chiabresalone, and to take special care of the human. Remember that he can understand all that you say. If it can be done safely in his weakened condition, hold him under sedation.”

“Yes, sir.”

The little amaut went away, and Tejef spied another of the okkitani-as,a young female whom her kind honored as extraordinarily attractive. This was not apparent to iduve eyes, but he trusted her for especial discretion and intelligence.

“Toshi, collect your belongings. You are going to perform an errand for me in Weissmouth.”

“The kamethi have now been sent to Priamos,” said Ashakh. “They will know nothing until they wake onworld. The shuttle crew will deliver them to local authorities for safekeeping.”

“I did somewhat regret sending them.” Chimele arose, activating as she did so the immense wall-screen that ran ten meters down the wall behind her desk. It lit up with the blue and green of Priamos, a sphere in the far view, with the pallor of its out-sized moon—the world’s redeeming beauty—to its left. She sighed seeing it, loving as she did the stark contrasts of the depths of space, lightless beauties unseen until a ship’s questing beam illumined them, the dazzling splendors of stars, the uncompromising patterns of dark-light upon stone or machinery. Yet she had a curiosity, a m’melakhia,to set foot on this dusty place of unappealing grasslands and deserts, to know what lives m’metaneilived or why they chose such a place.

“What manner of people are they?” she asked of Ashakh. “You have seen them close at hand. Would we truly be destroying something unique?”

Ashakh shrugged. “Impossible to estimate what they were. That is a question for Khasif. I am of the order of Navigators.”

“You have eyes, Ashakh.”

“Then—inexpertly—I should say that it is what one might expect of a civilization in dying: victims and victimizers, pointless destruction, a sort of mass urge to serach.They know they have no future. They have no real idea what we are; and they fear the amaut out of all proportion, not knowing how to deal with them.’

“Tejef’s serachwill be great beyond his merits if he causes us to destroy this little world.”

“It has already been great beyond his merits,” said Ashakh. “ Chaganokhruined this small civilization by guiding Tejef among them. It is ironic. If these humans had only known to let them escort Tejef in and depart unopposed, they would not have lost fleets to Chaganokh,the amaut would not have been attracted, and they might have had a fleet left to maintain their territories against the amaut if the invasion occurred. Likely then it would have been impossible for us to have traced Tejef before the time expired, and they would not now be in danger from us.”

“If the humans are wise, they will learn from this disaster; they will not fight us again, but let us pass where we will. Still, knowing what I do of Daniel, I wonder if they are that rational.”

“They have a certain elethia,” said Ashakh quietly.

“ Au,then you have been studying them after all. What have you observed?”

“They are rather like kallia,” said Ashakh, “and have no viable nasul-bond; consequently they find difficulty settling differences of opinion—rather more than kallia. Humans actually seem to consider divergence of opinion a positive value, but attach negative value to the taking of life. The combination poses interesting ethical problems. They also have a capacity to appreciate arrhei-akita,which amaut and kallia do not; and yet they have deep tendency toward permanent bond to person and place—hopelessly at odds with freedom such as we understand the word. Like world-born kallia, they ideally mate-bond for life; they also spend much of their energy in providing for the weaker members of their society, which activity has a very positive value in their culture. Surprisingly, it does not seem to have debilitated them; it seems to provide a nasul-substitute, binding them together. Their protective reaction toward weaker beings seems instinctive, extending even to lower life forms; but I am not sure what kind of feeling the harachiaof weakness evokes in them. I tend to think this behavior was basic to the civilization, and that what we see now is the work of humans in whom this response has broken down. Their other behavior consequently lacks human rationality.”

“In my own experience,” Chimele said ruefully, “behavior with this protective reaction also seems highly irrational.”

The door opened and there was Rakhi. A little behind him stood Chaikhe, the green robes of a katasatheproclaiming her condition to all about her; and when she saw Chimele she folded her hands and bowed her head very low, trembling visibly.

“Chaikhe,” said Chimele; and Ashakh, who was of Chaikhe’s sra,quickly moved between them; Rakhi did the same, facing Ashakh. This was proper: a protection for Chaikhe, a respect for Chimele.

“I am ashamed,” said Chaikhe, “to be so when you need me most, I am ashamed.”

This was ritual and truth at the same time, for it was proper for a katasatheto show shame before an orithain-tak,and Chimele had made clear to her a more than casual irritation. (“You are a person of kutikkase,” Chimele remembered saying to her: it had bitterly embarrassed the gentle Chaikhe, who prided herself on her chanokhia,but it was truly an unfortunate time for the nas-katasakketo go off on an emotional bent.)

“Later might have been more appropriate,” said Chimele. “But come, Chaikhe. I did not call you here to harm you.”

And while Chaikhe still maintained that posture of submission, Chimele came to her and took her by the hands. Then only did Chaikhe straighten and venture to look her in the eyes.

“We are sra,” said Chimele to her and to the others, “and we have always been close.” With a gesture she offered them to sit and herself assumed a plain chair among them. They looked confused; she did not find that surprising.

“Mejakh has been given a ship,” she said softly. “You know that she wanted it so. She had honor once. I debated it much, considering the present situation, but it seemed right to do. She is e-takkheand henceforth arrhei-nasul.”

“Hail Mejakh,” said Ashakh in a low voice, “for she truly meant to kill you, Chimele, and her takkhenoiswas almost strong enough to try it.”

“I perceive your disapproval.”

“I am takkhe.I agree to your decisions in this matter. At least there is no probability that she will seek union with either Tashavodhor Tejef.”

“I hope that she will approach Mijanotheand that they will see fit to take her. I am relieved to be rid of her, and anxious at once that she may attempt some private vaikkaon Tejef. But to destroy her without Khasif’s consent would have provoked difficulty with him and weakened the nasul.My alternatives were limited. She made herself e-takkhe.What else could I have done?”

Of course there was nothing else. The nasithiwere both uncomfortable and unhappy, but they put forward no opposition.

“ Mijanotheand Tashavodhhave been advised of Mejakh’s irresponsible condition,” Chimele continued, “and I have warned Khasif. Rakhi, I want her position constantly monitored. Apply what encouragement you may toward her joining Mijanotheor departing this star altogether.”

“Be assured I shall,” said Rakhi.

“We have bitter choices ahead in the matter of Tejef. You know that Daniel has been lost. Against the arastietheof Ashanome,Khasif himself has now become expendable.”

“Have you something in mind, Chimele,” asked Ashakh, frowning, “or are you finally asking advice?”

“I have something in mind, but it is not a pleasant choice. You are all, like Khasif, expendable.”

“And shall we die?” asked Rakhi somewhat wryly. “Chimele, I am a lazy fellow, I admit it. I have little m’melakhiaand the pursuit of vaikkais too much excitement for my tastes—”

The nasithismiled gently, for it was high exaggeration, and Rakhi was exceedingly takkhe.

“—so, well, but if we are doomed,” Rakhi said, “need we be uncomfortable in the process? Perhaps a transfer earthward at the moment of oblivion would suffice. Or if not, perhaps Chimele will honor us with her confidence.”

“No,” said Chimele, “no, Rakhi, a warning is all you are due at the moment. But”—her face became quite earnest—“I regret it. What I must do, I will do, even to the last of you.”

“Then I will go down first,” said Ashakh, “because I know that Rakhi would indeed be miserable; and because I do not want Chaikhe to go at all. Omit her from your reckoning, Chimele. She is katasatheand carries a life; Ashanomehas single lives enough for you to spend.”

“Inconvenient as this condition is,” said Chimele, “still Chaikhe will serve me when I require; but your request to go first I will gladly honor, and I will not treat Chaikhe recklessly.”

“It is not my wish,” said poor Chaikhe, “but I will give up my child to the dhisthis day if it will advantage Ashanome.”

Chimele leaned over to take the nasith’shand and pressed it gently. “Hail Chaikhe, brave Chaikhe. I am not of a disposition ever to become dhisais.I shall bear my children for Ashanome’s sake as I do other things, of sorithias.Yet I know how strong must be your m’melakhiafor the child: you are born for it, your nature yearns for it as mine does toward Ashanomeitself. I am disadvantaged before the enormity of your gift, and I mean to refuse it. I think you may serve me best as you are.”

“The sight of me is not abhorrent to you?”

“Chaikhe,” said Chimele with gentle laughter, “you are a great artist and your perception of chanokhiais usually unerring; but I find nothing abhorrent in your happiness, nor in your person. Now it is a bittersweet honor I pay you,” she added soberly, “but Tejef has always honored you greatly, and so, katasathe,once desired of him, you now become a weapon in my hands. How is your heart, Chaikhe? How far can you serve me?”

“Chimele,” Ashakh began to protest, but her displeasure silenced him and Chaikhe’s rejection of his defense finished the matter. He stretched his long legs out before him and studied the floor in grim silence.

“Once,” said Chaikhe, “indeed I was drawn to Tejef, but I am takkhewith Ashanomeand I would see him die by any means at all rather than see him take our arastiethefrom us.”

“Where Chaikhe is,” murmured Chimele, “I trust that all Ashanome’s affairs will be managed with chanokhia.”