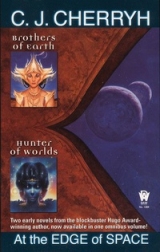

Текст книги "At the Edge of Space (Brothers of Worlds; Hunter of Worlds)"

Автор книги: C. J. Cherryh

Жанр:

Космическая фантастика

сообщить о нарушении

Текущая страница: 21 (всего у книги 36 страниц)

To wait.

There was an Order of things, and it was reasonable and productive. For one nas kame to defy the Orithain and die would accomplish nothing. An unproductive action was not a reasonable action, and an unreasonable action was not virtue, was not kastien.

Should he have died for nothing?

But all reasonable action on Ashanomeoperated in favor of the Orithain, who understood nothing of kastien.

Until the idoikkhehad locked upon his wrist, he had been a person of some elethia.He had been a man able to walk calmly through Kartos Station under the witness of others. He had even imagined the moment he had just passed, in a hundred different manners. But he had expected oblivion, a canceling of self—a state in which he was innocent.

He had accepted it. He would continue to accept it, every day of his life, and by its weight, that metal now warmed to the temperature of his own body, he would remember what it cost to say no.

He had despised the noi kame. But doubtless their ancestors had resolved the same as he, to live, to wait their chance, which only hid their fear; waiting, they had served the Orithain, and they died, and their children’s children knew nothing else.

Something stabbed at him behind his eyes. He caught at his face and reached for the support of the viewport. Waking. Conscious.

Isande.

It stopped. His vision cleared.

But it was coming. He stood still, waiting—impulses to flight, even to suicide beat along his nerves; but these things were futile, ikas.It was possible—he thought blasphemously—that kastiendemanded this patience of kallia because they were otherwise defenseless.

Slowly, slowly, something touched him, became pressure in that zone of his mind that had been opened. He shut his eyes tightly, feeling more secure as long as outside stimuli were limited. This was a being of his own kind, he reminded himself, a being who surely was in no happier state than himself.

It built in strength.

Different:that was the overwhelming impression, a force that ran over his nerves without his willing it, callous and unfamiliar. It invaded the various centers of his brain, probing one and another with painful rapidity. Light blazed and faded, equilibrium wavered, sounds roared in his ears, hot and cold affected his skin.

Then it invaded his thoughts, his memories, his inmost privacy.

O God!he thought he cried, like a man dying. There was a silence so dark and sudden it was like falling. He was leaning against the viewport, chilled by it. People were staring at him. Some even looked concerned. He straightened and shifted his eyes from the reflection to the stars beyond, to the dark.

“I am Isande.” There grew a voice in his mind that had tone without sound, as a man could imagine the sound of his own voice when it was silent. A flawed dim image of the concourse filled his eyes. He saw the viewport at a distance, marked a slender man who seemed tiny against it—all this overlaid upon his own view of space. He recognized the man for himself, and turned, seeing things from two sides at once. Imposed on his own self now was a distant figure he knew for Isande: he felt her exhaustion, her impatience.

“I’ll meet you in your quarters,” she sent.

Her turning shifted his vision, causing him to stagger off-balance; reflex stopped the image, screened her out. He suddenly realized he had that defense, tried it again—he could not cope with the double vision while either of them was moving. He shut it down, an irregular flutter of on-off. It was hard to will a thing that decisively, that strongly, but it could be done.

And he began to suspect Chimele had been honest when she told him that kamethi found the chiabresno terror. It was a power, a compensation for the idoikkhe,a door one could fling wide or close at will.

Only what territory lay beyond depended entirely on the conscience of another being—on two asuthi, one of whom might be little removed from madness.

He did not touch her mind again until he had opened the door of his quarters: she was seated in his preferred chair in a relaxed attitude as if she had a perfect right to his things. When he realized she was speculating on the pictures on the bureau she pirated the knowledge of his family from his mind, ripped forth a flood of memories that in his disorganization he could not prevent. He reacted with fury, felt her retreat.

“I’m sorry,” she said smoothly, shielding her own thoughts with an expertise his most concentrated effort could not penetrate. She gestured toward the other chair and wished him seated.

“These are my quarters,” he said, still standing. “Or do they move you in with me? Do they assume that too?”

Her mind closed utterly when she felt that, and he could not reach her. He had thought her beautiful when he first saw her asleep; but now that her body moved, now that those blue eyes met his, it was with an arrogance that disturbed him even through the turmoil of his other thoughts. There was a mind behind that pretty façade, strong-willed and powerful, and that was not an impression beautiful women usually chose to send him. He was not sure he liked it.

He was less sure he liked her, despite her physical attractions.

“I have my own quarters,” she said aloud. “And don’t be self-centered. Your choices are limited, and Iam not one of them.”

She ruffled through his thoughts with skill against which he had no defense, and met his temper with contempt. He thrust her out, but the least wavering of his determination let her slip through again; it was a continuing battle. He took the other chair, exhausted, beginning to panic, feeling that he was going to lose everything. He would even have struck her—he would have been shamed by that.

And she received that, and mentally backed off in great haste. “Well,” she conceded then, “I am sorry. I am rude. I admit that.”

“You resent me.” He spoke aloud. He was not comfortable with the chiabres.And what she radiated confirmed his impression: she tried to suppress it, succeeded after a moment.

“I wanted what you are assigned to do,” she said, “very badly.”

“I’ll yield you the honor.”

Her mind slammed shut, her lips set. But something escaped her barriers, some deep and private grief that touched him and damped his anger.

“Neither you nor I have that choice,” she said. “Chimele decides. There is no appeal.”

Chimele.He recalled the Orithain’s image with hate in his mind, expected sympathy from Isande’s, and did not receive it. Other images took shape, sendings from Isande, different feelings: he flinched from them.

For nine thousand years Isande’s ancestors had served the Orithain. She took pride in that.

Iduve,she sent, correcting him. Chimele isthe Orithain; the people are iduve.

The words were toneless this time, but different from his own knowledge. He tried to push them out.

The ship isAshanome, she continued, ignoring his awkward attempt to cast her back. WE areAshanome: five thousand iduve, seven thousand noi kame, and fifteen hundred amaut. The iduve call it a nasul, a clan. Thenasul Ashanome is above twelve thousand years old; the shipAshanome is nine thousand years from her launching, seven thousand years old in this present form. Chimele rules here. That is the law in this world of ours.

He flung himself to his feet, finding in movement, in any distraction, the power to push back Isande’s insistent thoughts. He began to panic: Isande retreated.

“You do not believe,” she said aloud, “that you can stop me. You could, if you believed you could.”

She pitiedhim. It was a mortification as great as any the iduve had set upon him. He rounded on her with anger ready to pour forth, met a frightened, defensive flutter of her hand, a sealing of her mind he could not penetrate.

“No,” she said. “Aiela—no. You will hurt us both.”

“I have had enough,” he said, “from the iduve—from noi kame in general. They are doing this to me—”

“—to us.”

“Why?”

“Sit down. Please.”

He leaned a moment against the bureau, stubborn and intractable; but she was prepared to wait. Eventually he yielded and settled on the arm of his chair, knowing well enough that she could perceive the distress that burned along his nerves, that threatened the remnant of his self control.

You fear the iduve,she observed. Sensible. But they do not hate; they do not love. I am Chimele’s friend. But Chimele’s language hasn’t a single word for any of those things. Don’t attribute to them motives they can’t have. There is something you must do in Chimele’s service: when you have done it, you will be let alone. Not thanked: let alone. That is the way of things.

“Is it?” he asked bitterly. “Is that all you get from them—to be left alone?”

Memory, swift and involuntary: a dark hall, an iduve face, terror. Thought caught it up, unraveled, explained. Khasif: Chimele’s half-brother. Yes, they feel. But if you are wise, you avoid causing it.Isande had escaped that hall; Chimele had intervened for her. It haunted her nightmares, that encounter, sent tremors over her whenever she must face that man.

To be let alone: Isande sought that diligently.

And something else had been implicit in that instant’s memory, another being’s outrage, another man’s fear for her—as close and as real as his own.

Another asuthe.

Isande shut that off from him, firmly, grieving. “Reha,” she said. “His name was Reha. You could not know me a moment without perceiving him.”

“Where is he?”

“Dead.” Screening fell, mind unfolding, willfully.

Dark, and cold, and pain: a mind dying and still sending, horrified, wide open. Instruments about him, blinding light. Isande had held to him until there was an end, hurting, refusing to let go until the incredible fact of his own death swallowed him up. Aiela felt it with her, her fierce loyalty, Reha’s terror—knew vicariously what it was to die, and sat shivering and sane in his own person afterward.

It was a time before things were solid again, before his fingers found the texture of the chair, his eyes accepted the color of the room, the sober face of Isande. She had given him something so much of herself, so intensely self, that he found his own body strange to him.

Did they kill him?he asked her: He trembled with anger, sharing with her: it was his loss too. But she refused to assign the blame to Chimele. Her enemies were not the iduve of Ashanome.His were.

He drew back from her, knowing with fading panic that it was less and less possible for him to dislike her, to find evil in any woman that had loved with such a strength.

It was, perhaps, the impression she meant to project. But the very suspicion embarrassed him, and became quickly impossible. She unfolded further, admitting him to her most treasured privacy, to things that she and Reha had shared once upon a time: her asuthe from childhood, Reha. They had played, conspired, shared their loves and their griefs, their total selves, closer by far than the confusion of kinswomen and kinsmen that had little meaning to a nas kame. For Isande there was only Reha: they had been the same individual compartmentalized into two discrete personalities, and half of it still wakened at night reaching for the other. They had not been lovers. It was something far closer.

Something to which Aiela had been rudely, forcibly admitted.

And he was an outsider, who hated the things she and Reha had loved most deeply. Bear with me,she asked of him. Bear with me. Do not attack me. I have not accepted this entirely, but I will. There is no choice. And you are not unlike him. You are honest, whatever else. You are stubborn. I think he would have liked you. I must begin to.

“Isande,” he began, unaccountably distressed for her. “Could I possibly be worse than the human? And you insist you wanted that.”

I could shield myself from that—far more skillfully than you can possibly learn to do to two days. And then I would be rid of him. But you—

Rid?He tried to penetrate her meaning in that, shocked and alarmed at once; and encountered defenses, winced under her rejection, heart speeding, breath tight. She turned off her conscience where the human was concerned. He was nothing to her, this creature. Anger, revenge, Reha—the human was not the object of her intentions: he simply stood in the way, and he was alien– alien!—and therefore nothing. Aiela would not draw her into sympathy with that creature. She would not permit it. NO!She had died with one asuthe, and she was not willing to die with another.

Why is he here?Aiela insisted. What do the iduve want with him?

Her screening went up again, hard. The rebuff was almost physical in its strength.

He was not going to obtain that answer. He had to admit it finally. He rose from his place and walked to the bureau, came back and sprawled into the chair, shaking with anger.

There was something astir among iduve, something which he was well sure Isande knew: something that could well cost him his life, and which she chose to withhold from him. And as long as that was so there would be no peace between them, however close the bond.

In that event she would not win any help from him, nor would the iduve.

No, she urged him. Do not be stubborn in this.

“You are Chimele’s servant. You say what you have to say. I still have a choice.”

Liar,she judged sadly, which stung like a slap, the worse because it was true.

Images of Chimele: ancestry more ancient than civilization among iduve, founded in days of tower-holds and warriors; a companion, a child, playing at draughts, elbows-down upon an izhkhcarpet, laughing at a m’metane’scleverness; Orithain—

–isolate, powerful: Ashanome’s influence could move full half the nasuliof the iduve species to Chimele’s bidding—a power so vast there could be no occasion to invoke it.

Sole heir-descendant of a line more than twelve thousand years old. Vaikka:revenge; honor; dynasty.

Involving this human,Aiela gleaned on another level.

But that was all Isande gave him, and that by way of making peace with him. She was terrified, to have given him only that much.

“Aiela,” she said, “you are involved too, because heis, and you were chosen for him. Even iduve die when they stand between an Orithain and necessity. So did Reha.”

I thought they didn’t kill him.

“Listen to me. I have lived closer to the iduve than most kamethi ever do. If Reha had been asuthe to anyone else but me, he might be alive now, and now you are here, you are Chimele’s because of me; and I am warning you, you will need a great deal of good sense to survive that honor.”

“And you lovea being like that.” He could not understand. He refused to understand. That in itself was a victory.

“Listen. Chimele doesn’t ask that you love her. She couldn’t understand it if you did. But she scanned your records and decided you have great chanokhia,great—fineness—for a m’metane.Being admired by any iduve is dangerous; but an Orithain does not make mistakes, Do you understand me, Aiela?”

Fear and love: noi kame lived by carefully prescribed rules and were never harmed—as long as they remembered their place, as long as they remained faceless and obscure to the iduve. The iduve did not insist they do so: on the contrary the iduve admired greatly a m’metanewho tried to be more than m’metane.

And killed him.

“There is no reason to be afraid on that score,” Isande assured him. “They do not harm us. That is the reason of the idoikkhei.You will learn what I mean.”

His backlash of resentment was so strong she visibly winced. She simply could not understand his reaction, and though he offered her his thoughts on the matter, she drew back and would not take them. Her world was enough for her.

“I have things to teach you,” he said, and felt her fear like a wall between them.

“You are welcome to your opinions,” she said at last.

“Thank you,” he said bitterly enough; but when she opened that wall for a moment he found behind it the sort of gentle being he had seen through Reha’s thoughts, terribly, painfully alone.

Dismayed, she slammed her screening shut with a vengeance, assumed a cynical façade and kept her mind taut, more burning than an oath. “And I will maintain my own,” she said.

3

Two days could not prepare him, not for this.

He looked on the sleeping human and still, despite the hours he had spent with Isande, observing this being by monitor, a feeling of revulsion went through him. The attendants had done their aesthetic best for the human, but the sheeted form on the bed still looked alien—pale coloring, earth-brown hair trimmed to the skull-fitting style of the noi kame, beard removed. He never shuddered at amaut: they were cheerful, comic fellows, whose peculiarities never mattered because they never competed with kallia; but this– this—was bound to his own mind.

And there was no Isande.

He had assumed—they had both assumed in their plans—that she would be with him. He had come to rely on her in a strange fashion that had nothing to do with duty: with her, he knew Ashanome,he knew the folk he met, and people deferred to his orders as if Isande had given them. She had been with him, a voice continually in his mind, a presence at his side; at times they had argued; at others they had even found reason to be awed by each other’s worlds. With her, he had begun to believe that he could succeed, that he could afterward settle into obscurity among the kamethi and survive.

He had in two days almost forgotten the weight of the bracelet upon his wrist, had absorbed images enough of the iduve that they became for him individual, and less terrible. He knew his way, which iduve to avoid most zealously, and which were reckoned safe and almost gentle. He knew the places open to him, and those forbidden; and if he was a prisoner, at least he owned a fellow-being who cared very much for his comfort—it was her own.

They were two: Ashanomewas vast: and it was true that kamethi were not troubled by iduve in their daily lives. He saw no cruelty, no evident fear—himself a curiosity among Isande’s acquaintances because of his origins: and no one forbade him, whatever he wished to say. But sometimes he saw in others’ eyes that they pitied him, as if some mark were on him that they could read.

It was the human.

As this went, he would live or die; and at the last moment, Chimele had recalled Isande, ordering her sedated for her own protection. I value you,Chimele had said. No. The risk is considerable. I do not permit it.

Isande had protested, furiously; and that in a kameth was great bravery and desperation. But Chimele had not used the idoikkhe;she had simply stared at Isande with that terrible fixed expression, until the wretched nas kame had gone, weeping, to surrender herself to the laboratory, there to sleep until it was clear whether he would survive. The iduve would destroy a kameth that was beyond help; she feared to wake to silence, such a silence as Reha had left. She tried to hide this from him, fearing that she would destroy him with her own fear; she feared the human, such that it would have taxed all her courage to have been in his place now—but she would have done it, for her own reasons. She would have stood by him too—that was the nature of Isande: honor impelled her to loyalty. It had touched him beyond anything she could say or do, that she had argued with Chimele for his sake; that she had lost was only expected: it was the law of her world.

“Take no chances,” she had wished him as she sank into dark. “Touch the language centers only, until I am with you again. Do not let the iduve urge you otherwise. And do not sympathize with that creature. You trust too much; it’s a disease with you. Feelings such as we understand do not reside in all sentient life. The iduve are proof enough of that. And who understands the amaut?”

What do they want of him?he had tried to ask. But she had left him then, and in that place that was hers there was quiet.

Now something else stirred.

He felt it beginning, harshly ordered medical attendants out: they obeyed. He closed the door. There was only the rush of air whispering in the ducts, all other sound muffled.

The darkness spotted across his vision, dimming senses. The human stirred, and light hazed where the dark had been. Then he discovered the restraints and panicked.

Aiela flung up barriers quickly. His heart was pounding against his ribs from the mere touch of that communication. He bent over the human, seized his straining shoulders and held him.

“Be still! Daniel, Daniel—be still.”

The human’s gasps for breath ebbed down to a series of panting sobs. The dark eyes cleared and focused on his. Because touch was the only safe communication he had, Aiela relaxed his grip and patted the human’s shoulder. The human endured it: he reminded Aiela of an animal soothed against its will, a wild thing that would kill, given the chance.

Aiela settled on the edge of the cot, feeling the human flinch. He spoke softly, tried amautish and kalliran words with him without success, and when he at last thought the human calm again, he ventured a mind-touch.

A miasma of undefined feeling came back: pain-panic-confusion. The human whimpered in fright and moved, and Aiela snatched his mind hack. His own hands were trembling. It was several moments before the human’s breathing rate returned to normal.

He tried talking to him once more, for a long time nothing more than that. The human’s eyes continually locked on his, animal and intense; at times emotion went through them visibly—a look of anxiety, of perplexity.

At last the being seemed calmer, closed his eyes for a few moments and seemed to slip away, exhausted. Aiela let him. In a little time more the brown eyes opened again, fixed upon his: the human’s face contracted a little in pain—his hand tensed against the restraints. Then he grew quiet again, breathing almost normally; he suffered the situation with a tranquility that tempted Aiela to try mind-touch again, but he refrained, instead left the bedside and returned with a cup of water.

The human lifted his head, trusted himself to Aiela’s arm for support while he drained the cup, and then sank back with a shortness of breath that had no connection with the effort. He wanted something. His lips contracted to a white line. He babbled something that had to do with amaut.

He did speak, then. Aiela set the cup down and looked down on him with some relief. “Is there pain?” he asked in the amautish tongue, as nearly as kalliran lips could shape the sounds. There was no evidence of comprehension. He sat down again on the edge.

The human stared at him, still breathing hard. Then a glance flicked down to the restraints, up again, pleading—repeated the gesture. When Aiela did nothing, the human’s eyes slid away from him, toward the wall. That was clear enough too.

It was madness to take such a chance. He knew that it was. The human could injure himself and kill him, quite easily.

He grew like Isande, who hated the creature, who would deal with him harshly; like the iduve, who created the idoikkheiand maintained matters on their terms, who could see something suffer and remain unmoved.

Better to die than yield to such logic. Better to admit that there was little difference between this wretched creature that at least tried to maintain its dignity, and a kalliran officer who walked about carrying iduve ownership locked upon his wrist.

“Come,” he said, loosed one restraint and the others in quick succession, dismissing iduve, dismissing Isande’s distress for his sake. Hechose, hechose for himself what he would do, and if he would die it was easier than carrying out iduve orders, terrifying this unhappy being. He lifted the human to sit, steadied him on the edge, found those pale strong hands locked on his arms and the human staring into his face in confusion.

Terror.

Daniel winced, grimaced and clutched at his head, discovered the incision and panicked. He hurled himself up, sprawled on the tiles, and lay there clutching his head and moaning, sobbing words of nonsense.

“Daniel.” Aiela caught his own breath, screening heavily: he knew well enough what the human was experiencing, that first horrible realization of the chiabres,the knowledge that his very self had been tampered with, that there was something else with him in his skull. Aiela felt pressure at his defenses, a dark force that clawed blindly at the edges of his mind, helpless and monstrous and utterly vulnerable at this moment, like something newborn.

He let the human explore that for himself, measure it, discover at last that it was partially responsive to his will. Aiela sat still, tautly screened, sweat coursing over his ribs; he would not admit it, he would not admit it—it was dangerous, unformed as it was. It moved all about the walls of his mind sensing something, seeking, aggressive and frightened at once. It acquired nightmare shape. Aiela snapped his vision back to nowand destroyed the image, refusing it admittance, saw the human wince and collapse.

He was not unconscious. Aiela knew it as he knew his own waking. He simply lay still, waiting, waiting—perhaps gathering his abused senses into some kind of order. Perhaps he was wishing to die. Aiela understood such a reaction.

Several times more the ugliness activated itself to prowl the edges of his mind. Each time it fled back, as if it had learned caution.

“Are you all right?” Aiela asked aloud. He used the tone, not the words. He put concern into it. “I will not touch you. Are you all right?”

The human made a sound like a sob, rolled onto an arm, and then, as if he suddenly realized his lack of elethiabefore a man who was still calmly seated and waiting for him, he made several awkward moves and dragged himself to a seated posture, dropped his head onto his arms for a moment, and then gathered himself to try to rise.

Aiela moved to help him. It was a mistake. The human flinched and stumbled into the wall, into the corner, very like the attitude he had maintained in the cell.

“I am sorry.” Aiela bowed and retreated back to his seat on the edge of the bed.

The human straightened then, stood upright, released a shaken breath. He reached again for the scar on his temple: Aiela felt the pressure at once, felt it stop as Daniel pulled his mind back.

“Daniel,” he said; and when Daniel looked at him curiously, suspiciously, he turned his head to the side and let Daniel see the scar that faintly showed on his own temple.

Then he opened a contact from his own direction, intending the slightest touch.

Daniel’s eyes widened. The ugliness reared up, terrible in its shape. Vision went. He screamed, battered himself against the door, then hurled himself at Aiela, mad with fear. Aiela seized him by the wrists, pressing at his mind, trying to ignore the terror that was feeding back into him. One of them knew how to control the chiabres:uncontrolled, it could do unthinkable harm. Aiela fought, losing contact with his own body: sweat poured over him, making his grip slide; his muscles began to shake, so that he could not maintain his hold at all; he knew himself in physical danger, but that inside was worse. He hurled sense after sense into play, seeking what he wanted, reading the result in pain that fed back into him, nightmare shapes.

And suddenly the necessary barrier crashed between them, so painful that he cried out: in instinctive reaction, the human had screened. There was separation. There was self-distinction.

He slowly disengaged himself from the human’s grip; the human, capable of attack, did not move, only stared at him, as injured as he. Perhaps the outcry had shocked him. Aiela felt after the human’s wrist, gripped it not threateningly, but as a gesture of comfort.

He forced a smile, a nod of satisfaction, and uncertainly Daniel’s hand closed—of a sudden the human gave a puzzled look, a half-laugh, half-sob.

He understood.

“Yes,” Aiela answered, almost laughed himself from sheer relief. It opened barriers, that sharing.

And he cried out in pain from what force the human sent. He caught at his head, signed that he was hurt.

Daniel tried to stop. The mental pressure came in spurts and silences, flashes of light and floods of emotion. The darkness sorted itself into less horrid form. It was not an attack. The human wanted;so long alone, so long helpless to tell—he wanted.He wept hysterically and held his hands back, trembling in dread and desire to touch, to lay hold on anyone who offered help.

Barriers tumbled.

Aiela ceased trying to resist. Exhaustion claimed him. Like a man rushing downhill against his will he dared not risk trying to stop; he concentrated only on preserving his balance, threading his way through half-explored contacts, unfamiliar patterns at too great a speed. Contacts multiplied, wove into pattern; sensations began to sort themselves into order, perceptions to arrange themselves into comprehensible form: body-sense, touch, equilibrium, vision—the room writhed out of darkness and took form about them.

Suddenly deeper senses were seeking structure. Aiela surrendered himself to Daniel’s frame of reference, where right was human-hued and wrong was different, where morality and normality took shapes he could hardly bear without a shudder. He reached desperately for the speech centers for wider patterns, establishing a contact desperately needed.

“I,” he said silently in human speech. “Aiela—I. Stop. Stop. Think slowly. Think of now. Hold back your thoughts to the pace of your words. Think the words, Daniel: my language, yours, no difference.”

“What—” the first response attempted. Apart from Aiela’s mind the sound had no meaning for the human.

“Go on. You understand me. You can use my language as I use yours. Our symbolizing facility is merged.”

“What—” Death was in his mind, gnawing doubt that almost forced them apart. “What is going to happen to me? What are you?”

His communication was a babble of kalliran and human language, amaut mixed in, voiced and thought, echoes upon echoes. He was sending on at least three levels at once and unaware which was dominant. Home, help, homekept running beneath everything.

“Be calm,” Aiela said. “You’re all right. You’re not hurt.”