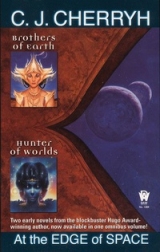

Текст книги "At the Edge of Space (Brothers of Worlds; Hunter of Worlds)"

Автор книги: C. J. Cherryh

Жанр:

Космическая фантастика

сообщить о нарушении

Текущая страница: 10 (всего у книги 36 страниц)

15

The ship rested as Kurt remembered it, tilted, the port still open. About it now were camped a hundred of the Tamurlin, hide-clothed and mostly naked, their huts of grass and sticks and hides encircling the shining alloy landing struts.

They came running to see the prizes their party had brought, these savage men and women and few starveling children. They shouted obscene threats at the nemet, but shied away, murmuring together when they realized Kurt was human. One of the young men advanced cautiously—though Kurt’s hands were tied—and others ventured after him. One pushed at Kurt, then hit him across the face, but the chief snatched him back, protective of his property.

“What band is he from?” one of them asked.

“Not from us,” said the chief. “None of ours.”

“He is human,” several of the others argued the obvious.

The chief took Kurt by the collar and pulled, taking his peldown to the waist, pushed him forward into their midst. “He’s not ours, whatever he is. Not of the tribes.”

Their reaction was near to panic, babbling excitement. They put out their filthy hands, comparing themselves with him, for their hides were sun-browned and creased with premature wrinkles from weather and wind, with dirt and grease ground into the crevices. They prodded at Kurt with leathery fingers, pulled at his clothing, ran their hands over his skin and howled with amusement when he cursed and kicked at them.

It was a game, with them running in to touch him and out again when he tried to defend himself; but when he tired of it and let them, that spoiled it and angered them. They hit, and this time it was in earnest. One of them in a fit of offended arrogance pushed him down and kicked him repeatedly in the side, and the lot of them roared with laughter at that, even more so when a little boy darted in and did the same. Kurt twisted onto his knees and tried to rise, and the chief seized him by the arm and hauled him up.

“Where from?” the chief asked.

“Offworld,” said Kurt from bloodied lips. He saw the ship beyond the chief’s shoulder, a sanctuary out of his own time that he could not reach. He burned with shame for their treatment of him, and for the nemet’s eyes on these his brothers, these shaggy, mindless, onetime lords of the earth. “That ship brought me here.”

“The Ship,” the others took it up. “The holy Ship! The Starship!”

“This is notthe Ship,” the chief shouted them down and pointed at it, his hand trembling with passion. “The curse-sign on it—this man is not what the Articles say.”

The Alliance emblem. Kurt had forgotten the sunburst emblem of the Alliance that was blazoned on the ship. They were Hanan. He followed the chief’s pointing finger, wondering with a sickness at the pit of his stomach how much of the war these savages recalled.

“A starman!” one of the young men shouted defiantly. “A starman! The Ship is coming!”

And the others took up the howl with wild-eyed fervor, the same ones who had lately thrown him in the dust.

“The Ship, ya, the Ship, the Ship, the machines and the armies!”

“They are coming!”

“Indresul Indresul! The waiting is over!”

The chief backhanded Kurt to the ground, kicked him to show his contempt, and there was a cry of resentment from the people. A youth ran in—for what purpose was never known. The chief dropped the boy with a single blow of his fist and rounded on the leaders of the dissent.

“And I am still captain here,” he roared, “and I know the Articles and the Writings, and who will come and argue them with me?”

One of the men looked as if he might, but when the captain came closer to him, he ducked his head and sidled off. The rebellion died into sullen resentment.

“You’ve seen the sign,” said the captain. “Maybe the Ship is near. But this little thing isn’t what the Writings predict.” He looked down at Kurt with threat in his eyes. “Where are the machines, the Ship as large as a mountain, the armies from the star-worlds that will take us to Indresul?”

“Not far away,” said Kurt, setting his face to lie, which was never a skill of his. “I was sent out from Aeolus to find you. Is this how you welcome me? That will be the last you ever see of Ships if you kill me.”

The captain was taken aback by that answer.

“Mother Aeolus,” cried one of the men, though he called it Elus, “the great Mother. He has seen the Great Mother of All Men.”

The captain looked at Kurt from under one brow, hating, just the least part uncertain. “Then,” he said, “what did she say to you?”

The lie closed in on him, complex beyond his own understanding. Aeolus—homeworld—confounded with the nemet’s Mother Isoi, Mother of Men: nemet religion and human hopes confused into reverence for a promised Ship. “She—lost you,” he said, gathering himself to his feet. They personified her: he hoped he understood that aright. “Her messenger was lost on the way hundreds of years ago, and she was angry, blaming you. But she has decided to send again, and now the Ship is coming, if my report to her is good.”

“How can her messenger wear the mark of Phan?” the captain asked. “You are a liar.”

The sunburst emblem of the ship. Kurt resisted the impulse to lose his dignity by looking where the captain pointed. “I am not a liar,” said Kurt. “And if you don’t listen to me, you’ll never see her.”

“You come from Phan,” the captain snarled, “from Phan, to lie to us and turn us over to the nemet.”

“I am human. Are you blind?”

“You camped with the earthpeople. You were no prisoner in that camp.”

Kurt straightened his shoulders and looked the man in the eyes, lying with great offense in his tone. “We thought you men were supposed to have these nemet under control. That’s what you were left here to do, after all, and you’ve had three hundred years to do that. So I had no real fear of the nemet and they were able to surprise me some time ago and take my weapons. It took me this long to escape from Nephane and come south. They hunted me down, with orders to bring me back to Nephane alive, so naturally they did me no harm in that camp, but that doesn’t mean the relationship was friendly. I don’t particularly Iike the nemet, but I’d advise you to save these three alive. When my captain comes down here, as he will, he’s going to want to question a few of the nemet, and these will do very well for that purpose.”

The captain bit his lip and gnawed his mustache. He looked at the three nemet with burning hatred and spit out an obscenity that had not much changed in several hundred years. “We kill them.”

“No,” Kurt said. “There’s need of them live and healthy.”

“Three nemet?” the captain snarled. “One. One we keep. You choose which one.”

“All three,” Kurt insisted, though the captain brandished his ax. It took all his self-possession not to flinch as the weapon made a pass at him.

Then the captain whirled the weapon in a glittering arc at the nemet, purposely defying him. The humans murmured, eyes glittering like the metal itself. The ax passed within an inch of Kta and of the next man.

“Choose!” the captain cried. “You choose, starman. One nemet. We take the other two.”

The howling began to be a moan. One of the little boys shrieked in glee and ran in, striking all three nemet with a stick.

“Which one?” the captain asked again.

Kurt kept his sickness from his face, saw Kta look at him, saw the nemet’s eyes sending a desperate and angry message to him, which he ignored, looking at the captain.

“The one on the left,” Kurt said. “That one. Their leader.”

One of the two nemet died before nightfall. The execution was in the center of camp, and there was no way Kurt could avoid watching from beginning to end, for the captain’s narrow eyes were on him more than on the nemet, watching his least reaction. Kurt kept his own eyes unfocused as much as possible, and his arms folded, so that his trembling was not evident.

The nemet was a brave man, and his last reasoned act was a glance at Kta—not desperate, but seeking approval of him. Kta was standing, hands bound: the lord of Elas gave the man a steadfast look, as if he had given him an order on the deck of their own ship; and the nemet died with what dignity the Tamurlin afforded him. They made a butchery of it, and the Tamurlin howled with excitement until the man no longer reacted to any torment. Then they finished him with an ax. As the blade came down, Kta’s self-control came near to breaking. He wept, his face as impassive as ever, and the Tamurlin pointed at him and laughed.

After that the captain ordered Kurt taken to his own shelter. There he questioned him, threatening him with not quite the conviction to make good the threats, accusing him over and over of lying. The captain was a shrewd man. At times there would come a light of cunning into his hair-shrouded eyes, and he doggedly refused to be led off on a tangent. Constantly he dragged the questioning back to the essential points, quoting from the versified Articles and the Writings of the Founders to argue against Kurt’s claims.

His name was Renols, or something which closely resembled that common Hanan name, and he was the only educated man in the camp. His power was his knowledge, and the moment Renols ceased to believe, or ceased to fear, then Renols could dispose of Kurt with lies of his own. The captain was a pragmatist, capable of it; Kurt was well certain he was capable of it.

The tent reeked of fire, of sweat, of the curious pungent leaf the Tamurlin chewed. One of his women lay in the corner against the wall, taking the leaves one by one. Her eyes had a fevered look. Sometimes the captain reached for one of the slim gray leaves and chewed at it half-heartedly. It perfumed the breath. Sweat began to bead on his temples. He grew calmer.

He offered the bowl of leaves to Kurt, insisting. At last Kurt took one, judiciously tucked it in his cheek, whole and un-bruised. Even so, it burned his mouth and spread a numbness that began to frighten him.

If he became drunk with it, he could say something he would not say: his capacity for the drug might be far less than Renols’.

“When,” asked Renols, “will the Ship come?”

“I told you. There’s machinery in my own ship. Let me in there and I can call my captain.”

Renols chewed and stared at him with his thick brows contracted. A dangerous look smoldered in his eyes. But he took another leaf and held out the bowl to Kurt a second time. His hands were stubby-fingered, the nails broken, the knuckles ridged with cut-scars.

Kurt took a second leaf and carefully eased that to the same place as the first.

The calculating look remained in Renols’ eyes. “What sort of man is he, this captain?”

The understanding began to come through. If a ship came, if Mother Aeolus did send it and all points of his prisoner’s tale proved true, then Renols would be faced with someone of greater authority than himself. He would perhaps become a little man. Renols must dread the Ship; it was in his own, selfish interests that there not be one.

But it was also remotely possible that his prisoner would be an important man in the near future, so Renols must fear him. Kurt reckoned that too, and reckoned uneasily that familiarity might well overcome Renols’ fear, when Aeolus’ messenger turned out to be only mortal.

“My captain,” said Kurt, embroidering the tale, “is named Ason, and Aeolus has given him all the weapons that you need. He will give them to you and show you their use before he returns to Aeolus to report.”

The answer evidently pleased Renols more than Renols had expected. He grunted, half a laugh, as if he took pleasure in the anticipation.

Then he gave orders to one of the sallow-faced women who sat nearby. She laid the child she had been nursing in the lap of the nearest woman, who slept in the after-effects of the leaf, and went out and brought them food. She offered first to Renols, then to Kurt.

Kurt took the greasy joint in his fingers and hesitated, suddenly fearing the Tamurlin might not be above cannibalism. He looked it over, relieved to find no comparison between this joint and human or nemet anatomy. Starvation and Renols’ suspicious stare overcame his other scruples and he ate the unidentified meat, careful with each bite not to swallow the leaves tucked in his cheek. The meat, despite the strong medicinal taste of the leaves, had a musty, mildewed flavor that almost made him retch. He held his breath and tried not to taste it, and wiped his hands on the earthen floor when he was done.

The captain offered him a second piece, and stopped in the act.

From outside there came a disturbance. Laughter. Someone shrieked in pain.

Renols put down the platter of meat and went out to speak with the man at the entry to the shelter.

“You swore,” said Kurt when he came back.

“We’re keeping yours,” said Renols. “The other one is ours.”

The confusion outside grew louder. Renols looked torn between annoyance at the interruption and desire to see what was passing outside. Abruptly he called in the man at the entry, tersely bidding him take Kurt to confinement.

The commotion sank away into silence. Kurt listened, teeth clamped tight against the heaving of his stomach. He had spit out the leaves there in the darkness of the shelter where they had left him, hands tied around one of the two support posts. He twisted until he could dig with his fingers in the hard dirt floor and bury the rejected leaves.

There was a bitter taste in his mouth now. His vision blurred, his pulse raced, his heart crashed against his ribs. He began to be hazy-minded, and slept a time.

Footsteps in the dust outside aroused him. Shadows entered the moonlight-striped shelter, pulling a loose-limbed body with them. It was Kta. They tied the semiconscious nemet to the other post and left him.

After a time Kta lifted his head and leaned it back against the post. He did not speak or look at Kurt, only stared off into the dark, his face and body oddly patterned with moonlight through the woven-work.

“Kta,” said Kurt finally. “Are you all right?”

Kta made no reply.

“Kta,” Kurt pleaded, reading anger in the set of the nemet’s jaw.

“Is it to you,” Kta’s hoarse voice replied, “is it to you that I owe my life? Do I understand that correctly? Or do I believe instead the tale you tell to the umani?”

“I am doing all I can.”

“What is it you want from me?”

“I am trying to save our lives,” Kurt said. “I am trying to get you out of here. You know me, Kta. Can you take seriously any of the things I have told them?”

There was a long silence. “Please,” said Kta in a broken voice, “please spare me your help from now on.”

“Listen to me. There are weapons in the ship if I can convince them to let me in there. If I can fire its engines I can burn this nest out.”

“I will forgive you,” said Kta, “when you do that.”

“Are you,” Kurt asked after a moment, “much hurt?”

“I am alive,” Kta answered. “Does that not satisfy you?—Shall I tell you what they did to the boy, honored friend?”

“I could not stop it,—Kta, look at me. Listen. Is there any hope at all from Tavi?If we could get free, could we find our way there?”

There was no answer.

“Kta,—where is your ship anchored?”

“Why? So you can buy our lives with that too?”

“Do you think I mean to tell—”

“They are your kind, human. It would be possible to survive,—if you could buy your life. I will not give you Tavi.”

Against such bitterness there was no answer. Kurt swallowed at the resentment and the hurt that rose in his throat; he held his peace after that. He wanted no more truth from Kta.

The silence wore on, two-sided. At last it was Kta who turned his head. “What are you fighting for?” he asked.

“I thought you had drawn your conclusion.”

“I am asking. What are you trying to do?”

“To save your life. And mine.”

“What use is that to either of us under these terms?”

Kurt twisted toward him. “What use is it to give in to them? Is it sense to let them kill you and do nothing to help yourself?”

“Stop protecting me. I am better dead.”

“Like theydied? Like that?”

“Show me,” said Kta, his voice shaking, “show me what you can do against these creatures. Put a weapon in my hands or even get my hands free and I will die well enough. But what dignity is there in living like this? Give me a reason. Tell me something I could have told the men they killed, why I have to live, when I should have died before them.”

“Kta, tell me, is there any possible chance of reaching Tavi?”

“The coast is leagues away. They would overtake us. This ship of yours. Is it true what you said, that you could burn them out?”

“Everyone would die,—you too, Kta.”

“You know how much that means to me. Light of heaven, what manner of world is yours? Why did you have to interfere?”

“I did the best I knew to do.”

“You were wrong,” said Kta.

Kurt turned away and let the nemet alone, as he so evidently wanted to be. Kta had reason enough to hate humanity. Almost all he had ever loved was dead at the hands of humans, his home lost, his hearth dead, now even the few friends he had left slaughtered before his eyes. His parents,—Hef,—Mim,—himself. Elas was dying. To this had human friendship brought the lord of Elas, and most of it was his own friend’s doing.

In time, Kta seemed to sleep, his head sunk on his breast, his breathing heavy.

A shadow crept across the slatting outside, a ripple of darkness that bent at the door, crept inside the shelter. Kurt woke, moved, began a cry of warning. The shadow plummeted, holding him, clamping a rough, calloused hand over his mouth.

The movement wakened Kta, who jerked, and a knife flashed in the dim light as the intruder drove for Kta’s throat.

Kurt twisted, kicked furiously and threw the would-be assassin tumbling. He righted himself, and a feral human face stared at both of them, panting, the knife still clenched for use.

The human advanced the knife, demonstrating it to them, ready. “Quiet,” he hissed. “Stay quiet.”

Kurt shivered, reaction to the near-slaughter of Kta. The nemet was unharmed, breathing hard, his eyes also fixed on the wild-haired human.

“What do you want?” Kurt whispered.

The human crept close to him, tested the cords on his wrists. “I’m Garet,” said the man. “Listen. I will help you.”

“Help me?” Kurt echoed, still shuddering, for he thought the man might be mad. The leaf-smell was about him. Feverish hands sought his shoulders. The man leaned close to whisper yet more softly.

“You can’t trust Renols, he hates the thought of the Ship. He’ll find a way to kill you. He isn’t sure yet, but he’ll find a way. I could get you into your ship tonight. I could do that.”

“Cut me free,” Kurt replied, snatching at any chance.

“I coulddo that.”

“What do you want, then?”

“You’ll have the weapons in the little ship. You can kill Renols then. Iwill help you. Iwill be second and I will go on helping you.”

“You want to be captain?”

“You can make me that, if I help you.”

“It’s a deal,” said Kurt, and held his breath while the man made a final consideration. He dared not ask Kta’s freedom too. He dared not turn on Garet and take the knife. The slim chance there was in the situation kept him from risking it; in silence, once inside the ship, he could handle Garet and stand off Renols.

The knife haggled at the cords, parting the tough fiber and sending the blood excruciatingly back to his hands. He rose up carefully, for Garet held the knife ready against him if he moved suddenly.

Then Garet’s eyes swept toward Kta. He bent toward him, blade extended.

Kurt caught his arm, fronted instantly by Garet’s bewildered suspicion, and for a moment fear robbed Kurt of any sense to explain.

“He is mine,” Kurt said.

“We can catch a lot of nemet,” said Garet. “What’s this one to you?”

“I know him,” said Kurt. “And I can get cooperation out of him. He’s not about to cry out, because he knows he’d die; he knows I’m his only chance of staying alive, so eventually he’ll tell me all I ask of him.”

Kta looked up at both of them, well able to understand. Whether it was consummate acting or fear of Garet or fear of human treachery, he looked frightened. He was among aliens. Perhaps it even occurred to him that he could have been long deceived.

Garet glowered, but he thrust the knife into his belt and led the way out into the tangle of huts outside.

“Sentries?” Kurt breathed into his ear.

Garet shook his head, drew him further through the village, up to the landing struts, the extended ladder. A sentry did stand there. Garet poised to throw, knife balanced between his fingertips. He drew back—

–the hiss and chunk!of an arrow toppled him, clawing at the ground. The sentry crouched and whirled, and men poured out of the dark. Kurt went down under a triple assault, struggling and kicking as they hauled him where they would take him, up to the ladder.

Renols was there, ax in hand. He prodded Kurt in the belly with it. His ugly face contorted further in a snarl of anger.

“Why?” he asked.

“He came,” said Kurt, “threatened to kill me if I didn’t come at once. Then he told me you were planning to kill me. I didn’t know what to believe. But this one had a knife, so I kept quiet.”

“Sentries are dead,” another man reported. “Six men are dead, throats cut. One of our scouts hasn’t come back either.”

“Garet’s brothers,” Renols said, and looked at the men who surrounded him. “His folk’s doing. Find his women and his brats. Give them to the dead men’s families, whatever they like.”

“Captain,” said that man, biting his lip nervously. “Captain, the Garets are a big family. Their kin is in the Red band too. If they get to them with some story—”

“Get them,” said Renols. “Now.”

The men separated. Those who held Kurt remained. Renols looked up at the entry to the ship, thought silently, then nodded to his men, who brought Kurt away as they walked through the camp. They were quiet. Not a sound came from the encampment. Kurt walked obediently enough, although the men made it harder for him out of spite.

They came to the hut from which he had escaped. Renols stooped and looked inside, where Kta was still tied.

He straightened again. “The nemet is still alive,” he said. Then he looked at Kurt from under one brow. “Why didn’t Garet kill him?”

Kurt shrugged. “Garet hit him. I guess he was in a hurry.”

Renols’ scowl deepened. “That isn’t like Garet.”

“How should I know? Maybe Garet thought he might fail tonight and didn’t want a dead nemet for proof of his visit.”

Renols thought that over. “So. How did he know you wouldn’t raise an alarm?”

“He didn’t. But it makes sense I’d keep quiet. How am I to know whose story to believe?”

Renols snorted. “Put him inside. We’ll catch one of the Garets alive and then we’ll see about it.”

The human left. Kurt tested the strength of the new cords, which were unnecessarily tight and rapidly numbed his hands—a petty measure of their irritation with him. He sighed and leaned his head back against the post, ignoring Kta’s staring at him.

There was no chance to discuss matters. Kta seemed to sense it, for he said nothing. Someone stood not far from the hut, visible through the matting.

Quite probably, Kurt thought, the nemet had added things up for himself. Whether he had then reached the right conclusion was another matter.

Eventually first light began to bring a little detail to the hut. Kta finally slept. Kurt did not.

Then a stir was made in the camp, men running in the direction of Renols’ hut. Distant voices were discussing something urgently. The commotion spread, until people were stirring about in some alarm.

And Renols’ lieutenants came to fetch them both, handling them both harshly as they hurried them toward Renols’ shelter.

“We found Garet’s brothers,” Renols said, confronting Kurt.

Kurt stared at him, neither comforted nor alarmed by that news. “Garet’s brothers are nothing to me.”

“We found them dead. All of them. Throats cut. There were tracks of nemet—sandal-wearing.”

Kurt glanced at Kta, not needing to feign shock.

“Two of our searchers haven’t come back,” said Renols. “You say this one is a chief among the nemet. A lord. Probably they’re his. Ask him.”

“You understood,” Kurt said in Nechai. “Say something.”

Kta set his jaw. “If you think to buy time by giving them anything from me, you are mistaken.”

“He has nothing to say,” said Kurt to Renols.

Renols did not look surprised. “He will find something to say,” he promised. “Astin, get a guard doubled out there. No women to go out of camp today. Raf, bring the nemet to the main circle.”

It would be possible, Kurt realized with a cold sickness at the heart, it would be possible to play out the game to the end. Kta would not betray him any more than he would betray the men of Tavi.To let Kta die might buy him the hour or so needed to hope for rescue. Possibly Kta would not even blame him. It was always hard to know what Kta would consider a reasonable action.

He followed along after those who took Kta—Kta with his spine stiff and every line of him braced to resist, but making not a sound. Kurt himself went docilely, his eyes scanning the hostile crowd that gathered in ominous silence.

He let it continue to the very circle, where the sand was still dark-spotted with the blood of the night before. He feared he would not have the courage to commit so senseless an act, giving up both their lives. But when they tried to put Kta to the ground, he scarcely thought. He tore loose, hit one man, stooped, jerked the ax from his startled hand and swung it toward those who held Kta.

The nemet reacted with amazing agility, swung one man into the path of the ax, kneed the other, snatched a dagger and applied it with the blinding speed he could use with the ypan.The men clutched spurting wounds and went down howling and writhing.

“Archers!” Renols bellowed. There was a great clear space about the area. Kurt and Kta stood back to back, men crowding each other to get out of the way. Renols was closest.

Kurt charged him, ax swinging. Renols went down with his side open, rolling in the dust. Other men scrambled out of the way as he kept swinging. Kta stayed with him. Their area changed. People fled from them screaming.

“Shoot them!” someone else shrieked.

Then all chaos broke loose, a hoarse cry from the rear of the crowd. Some of the Tamurlin turned screaming in panic, their cries swiftly drowned in the sounds of battle in the center of the crowd.

Kta jerked at Kurt’s arm and pointed—both of them for the moment stunned by the appearance of nemet among the Tamurlin, the flash of bright-edged swords in the sunlight. No Tamurlin offered them fight anymore: the humans were trying more to escape than to fight, and soon there were only nemet around them. The humans had vanished into the brush.

Now with Kurt behind him, Kta stood in the clear, with dagger in hand and the dead at his feet, and the nemet band raised a cheer.

“Lord Kta!” they cried over and over. “Lord Kta!” And they came to him, bloody swords in hand, and knelt down in the dust before their almost-naked and much-battered lord. Kta held out his hand to them, dropping the blade, and turned palm upward to heaven, to the cleansing light of the sun.

“ Ei,my friends,” he said, “my friends, well done.”

Val t’Ran, the officer next in command after Bel t’Osanef, rose from his knees and looked as if he would gladly have embraced Kta, if such impulses belonged to nemet. Tears shone in his eyes. “I thank heaven we were in time, Kta-ifhan, and I would have reckoned we could not be.”

“It was you who killed the humans outside the camp, was it not?”

“Aye, my lord, and we feared they had spoiled our ambush. We thought we might have been discovered by that. We were very careful stalking the camp, after that.”

“It was well done,” said Kta again, with great feeling, and held out his hand to the boy Pan, who had come with the rescuers. “Pan, it was you who brought them?”

“Yes, sir,” said the youth. “I had to run, sir, I had to. I hated to leave you. Tas and I—we thought we could do more by getting to the ship—but he died of his wound on the way.”

Kta swallowed heavily. “I am sorry, Pan. May the Guardians of your house receive him kindly.—Let us go. Let us be out of this foul place.”

Kurt saw them prepare to move out, looked down at what weight was clenched in his numb hand, saw the ax and his arm bloodstained to the shoulder. He let it fall, suddenly shaking in every limb. He stumbled aside from all of them, bent over in the lee of a hut and was sick for some few minutes until everything had emptied out of his belly—drugs, Tamurlin food. But the sights that stayed in his mind were something over which he had no such power. He took dust and rubbed at the blood until his skin stung with the sandy dirt and the spots were gone. In a deserted hut he found a gourd of water and drank and washed his face. The place stank of leaf. He stumbled out again into the sunlight.

“Lord Kurt,” said one of the seamen, astonished to find him. “Kta-ifhan is frantic. Come. Hurry. Come, please.”

The nemet looked strange to him, alien, the language jarring on his ears. Human dead lay around. The nemet were leaving. He felt no urge to go among them.

“Sir.”

Fire roared near him; a wave of heat brought him to alertness. They were setting fire to the village. He stared about him like a man waking from a dream.

He had pulled a trigger, pressed a button and killed, remotely, instantly. He had helped to fire a world, though his post was noncombat. They had been minute, statistical targets.

Renols’ astonished look hung before him. It had been Mim’s.

He lay in the dust, with its taste in his mouth and his lips cut and his cheek bruised. He did not remember falling. Gentle alien hands lifted him, turned him, smoothed his face.

“He is fevered,” Pan’s clear voice said out of the blaze of the sun. “The burns, sir—the sun, the long walk—”

“Help him,” said Kta’s voice. “Carry him if you must. We must get clear of this place. There are other tribes.”

The journey was a haze of brown and green, of sometime drafts of skin-stale water. At times he walked, hardly knowing anything but to follow the man in front of him. Toward the last, as their way began to descend to the sea and the day cooled, he began to take note of his surroundings again. Losing the contents of his stomach a second time, beside the trail, made him weak, but he was free of the nausea and his head was clearer afterwards. He drank telise,the kindly seaman who offered it bidding him keep the flask; it only occurred to him later that using something a sick human had used would be repugnant to the man. It did not matter; he was touched that the man had given it up for his sake.