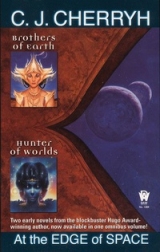

Текст книги "At the Edge of Space (Brothers of Worlds; Hunter of Worlds)"

Автор книги: C. J. Cherryh

Жанр:

Космическая фантастика

сообщить о нарушении

Текущая страница: 14 (всего у книги 36 страниц)

19

Keys rattled. Kurt stirred out of the torpor of long waiting. Suddenly he realized it was not breakfast. Too many people were in the hall: he heard their moving, the insertion of the key. Another of the moods of Ylith-methi, he reckoned.

Or it was an execution detail, and he was about to learn what had become of Kta.

Lhe led them, Lhe with fatigue-marks under his eyes and his normally impeccable hair disarranged. A tai,a short sword, was through his belt.

“Wait down the hall,” he said to the others.

They did not want to go. He repeated the order, this time with wildness in his voice, and they almost fled his presence.

No!Kurt started to protest, rising off his cot, but they were gone. Lhe closed the door and stood with his hand clenched on the hilt of the tai.

“I am t’Nethim,” said Lhe. “My father’s business is with Vel t’Elas. Mine is with you. Mim t’Nethim was my cousin.”

Kurt recovered his dignity and bowed slightly, ignoring the threat of the fury that trembled in Lhe’s nostrils. After such a point, there was little else to do. “I honored her,” he said, “very much.”

“No,” said Lhe. “That you did not.”

“Please. Say the rites for her.”

“We have said rites, with many prayers for the welfare of her soul. Because of Mim t’Nethim we have spoken well of Elas to our Guardians for the first time in centuries: even in ignorance, they sheltered her. But other things we will not forgive. There is no peace between the Guardians of Nethim and you, human. They do not accept this disgrace.”

“Mim thought them in harmony with her choice,” said Kurt. “There was peace in Mim. She loved Nethim and she loved Elas.”

It did not greatly please Lhe, but it affected him greatly. His lips became a hard line. His brows came as near to meeting as a nemet’s might.

“She was consenting?” he asked. “Elas did not command this of her, giving her to you?”

“At first they opposed it, but I asked Mim’s consent before I asked Elas. I wished her happy, t’Nethim. If you are not offended to hear it,—I loved her.”

A vein beat ceaselessly at Lhe’s temple. He was silent a moment, as if gathering the self-control to speak. “We are offended. But it is clear she trusted you, since she gave you her true name in the house of her enemies. She trusted you more than Elas.”

“No. She knew I would keep that to myself; but it was not fear of Elas. She honored Elas too much to burden their honor with knowing the name of her house.”

“I thank you, that you confessed her true name to the Methi so we could comfort her soul. It is a great deal,” he added coldly, “that we thanka human.”

“I know it is,” said Kurt, and bowed, courtesy second nature by now. He lifted his eyes cautiously to Lhe’s face; there was no yielding there.

Scurrying footsteps approached the door. With a timid knock, a lesser guardsman cracked the door and awkwardly bowed his apology. “Sir. Sir. The Methi is waiting for this human. Please, sir, she has sent t’Iren to ask about the delay.”

“Out,” Lhe snapped. The head vanished out of the doorway. Lhe stood for a moment, fingers white on the hilt of the tai.Then he gestured abruptly to the door. “Human. You are not mine to deal with. Out.”

The summons this time was to the fortress rhmei,into a gathering of the lords of Indresul, shadowy figures in the firelit hall of state. Ylith waited beside the hearthfire itself, wearing again the wide-winged crown, a slender form of color and light in the dim hall, her gown the color of flame and the light glancing from the metal around her face.

Kurt went down to his knees and on his face without being forced, despite that a guard held him there with the butt of a spear in his back.

“Let him sit,” said Ylith. “He may look at me.”

Kurt sat back on his heels, amid a great murmuring of the Indras lords, and he realized to his hurt that they murmured against that permission. He was not fit to meet their Methi as even a humble chanmight, making a quick and dignified obeisance and rising. He laced his hands in his lap, proper for a man who had been given no courtesy of welcome, and kept his head bowed despite the permission. He did not want to stir their anger. There was nowhere to begin with them, to whom he was an animal; there was no protest and no action that would make any difference to them.

“T’Morgan,” Ylith insisted softly.

He would not, even for her. She let him alone after that, and quietly asked someone to fetch Kta.

It did not take long. Kta came of his own volition, as far as the place where Kurt knelt, and there he too went to his knees and bowed his head, but he did not make the full prostration and no one insisted on it. He was at least without the humiliation of the iron band that Kurt still wore on his ankle.

If they were to die, Kurt thought wildly, irrationally, he would ask them to remove it. He did not know why it mattered, but it did: it offended his pride more than the other indignities, to have something locked on his person against which he had no power. He loathed it.

“T’Elas,” said the Methi, “you have had a full day to reconsider your decision.”

“Great Methi,” said Kta in a voice faint but steady, “I have given you the only answer I will ever give.”

“For love of Nephane?”

“Yes.”

“And for love of the one who destroyed your hearth?”

“No. But for Nephane.”

“Kta t’Elas,” said the Methi, “I have spoken at length with Vel t’Elas. They would take you to the hearth of your Ancestors, and I would permit that, if you would remember that you are Indras.”

He hesitated long over that. Kurt felt the anxiety in him; but he would not offend Kta’s dignity by turning to urge him one way or the other.

“I belong to Nephane,” said Kta.

“Will you then refuse me, will you directly refuse me,t’Elas, knowing the meaning of that refusal?”

“Methi,” pleaded Kta, “let me be, let me alone in peace. Do not make me answer you.”

“Then you were brought up in reverence of Indras law and the Ind.”

“Yes, Methi.”

“And you admit that I have the authority to require your obedience? That I can curse you from hearth and from city, from all holy rites, even that of burial? That I have the power to consign your undying soul to perdition to all eternity?”

“Yes,” said Kta, and his voice was no more than a whisper in that deathly silence.

“Then, t’Elas,—I am sending you and the human t’Morgan to the priests. Consider, consider well the answers you will give them.”

The temple lay across a wide courtyard, still within the walls of the Indume, a cube of white marble, vast beyond all expectation. The very base of its door was as high as the shoulder of a man, and within the triangular rhmeiof the temple blazed the phusmehaof the greatest of all shrines, the hearthfire of all mankind.

Kta stopped at the threshold of the inner shrine, that awful golden light bathing his sweating face and reflecting in his eyes. He had an expression of terror on his face such as Kurt had never seen in him. He faltered and would not go on, and the guards took him by the arms and led him forward into the shrine, where the roar of the fire drowned the sound of their steps.

Kurt started to follow him, in haste. A spearshaft slammed across his belly, doubling him over with a cry of pain, swallowed in the noise.

When he straightened in the hands of the guards, barred from that holy place, he saw Kta at the side of the hearthfire fall to his face on the stone floor. The guards with him bowed and touched hands to lips in reverence, bowed again and withdrew as white-robed priests entered the hall from beyond the fire.

One was the elderly priest who had defended him to the Methi, the only one of all of them in whom Kurt had hope.

He jerked free, cried out to the priest, the shout also swallowed in the roar; Kta had risen and vanished with the priests into the light.

His guards recovered Kurt, snatching him back with violence he was almost beyond feeling.

“The priest,” he kept telling them. “That priest, the white-haired one,—I want to speak with him. Can I not speak with him?”

“Observe silence here,” one said harshly. “We do not know the priest you mean.”

“That priest!” Kurt cried, and jerked loose, threw a man skidding on the polished floor and ran into the rhmei,flinging himself facedown so close to the great fire bowl that the heat scorched his skin.

How long he lay there was not certain. He almost fainted, and for a long time everything was red-hazed and the air was too hot to breathe; but he had claimed sanctuary, as Mother Isoi had claimed it first in the Song of the Ind, when Phan came to kill mankind.

White-robed priests stood around him, and finally an aged and blue-veined hand reached down to him, and he looked up into the face he had hoped to find.

He wept, unashamed. “Priest,” he said, not knowing how to address the man with honor, “please help us.”

“A human,” said the priest, “ought not to claim sanctuary. It is not lawful. You are a pollution on these holy stones. Are you of our religion?”

“No, sir,” Kurt said.

The old man’s lips trembled. It might have been the effect of age, but his watery eyes were frightened.

“We must purify this place,” he said, and one of the younger priests said, “Who will go and tell this thing to the Methi?”

“Please,” Kurt pleaded, “please give us refuge here.”

“He means Kta t’Elas,” said one of the others, as if it was a matter of great wonder to them.

“He is house-friend to Elas,” said the old man.

“Light of heaven,” breathed the younger. “Elas—with this?”

“Nethim,” said the old man, “is also involved.”

“ Ai,” another murmured.

And together they gathered Kurt up and brought him with them, talking together, their steps beginning to echo now that they were away from the noise of the fire.

Ylith turned slowly, the fine chains of her headdress gently swaying and sparkling against her hair, and the light of the hearthfire of the fortress leaped flickering across her face. With a glance at the priest she settled into her chair and sat leaning back, looking down at Kurt.

“Priest,” she said at last, “you have reached some conclusion, surely, after holding them both so long a time.”

“Great Methi, the College is divided in its opinion.”

“Which is to say it has reached no conclusion, after three days of questioning and deliberation.”

“It has reached several conclusions, however—”

“Priest,” exclaimed the Methi in irritation, “yea or nay?”

The old priest bowed very low. “Methi, some think that the humans are what we once called the godkings, the children of the great earth-snake Yr and of the wrath of Phan when he was the enemy of mankind, begetting monsters to destroy the world.”

“This is an old, old theory, and the godkings were long ago, and capable of mixing blood with man. Has there ever been a mixing of human blood and nemet?”

“None proved, great Methi. But we do not know the origin of the Tamurlin, and he is most evidently of their kind; now you are asking us to resolve, as it were, the Tamurlin question immediately, and we do not have sufficient knowledge to do so, great Methi.”

“You have him.I sent him to you for you to examine. Does he tell you nothing?”

“What he tells us is unacceptable.”

“Does he lie? Surely if he lies, you can trap him.”

“We have tried, great Methi, and he will not be moved from what he says. He speaks of another world and another sun. I think he believes these things.”

“And do you believe them, priest?”

The old man bowed his head, clenching his aged hands. “Let the Methi be gracious: these matters are difficult or you would not have consulted the College. We wonder this: if he is not nemet, what could be his origin? Our ships have ranged far over all the seas, and never found his like. When humans will to do it, they come to us, bringing machines and forces our knowledge does not understand. If he is not from somewhere within our knowledge, then,—forgive my simplicity—he must still be from somewhere. He calls it another earth. Perhaps it is a failure of language, a misunderstanding,—but where in all the lands we know could have been his home?”

“What if there was another? How would our religion encompass it?”

The priest turned his watery eyes on Kurt, kneeling beside him. “I do not know,” he said.

“Give me an answer, priest. I will make you commit yourself. Give me an answer.”

“I—had rather believe him mortal than immortal, and I cannot quite accept that he is an animal. Forgive me, great Methi, what may be heresy to wonder,—but Phan was not the eldest born of Ib. There were other beings, whose nature is unclear. Perhaps there were others of Phan’s kind. And were there a thousand others, it makes the yhiano less true.”

“This is heresy, priest.”

“It is,” confessed the priest. “But I do not know an answer otherwise.”

“Priest, when I look at him, I see neither reason nor logic. I question what should not be questioned. If this is Phan’s world, and there is another,—then what does this foretell, this—intrusion—of humans into ours? There is power above Phan’s, yes; but what can have made it necessary that nature be so upset, so inside-out? Where are these events tending, priest?”

“I do not know. But if it is Fate against which we struggle, then our struggle will ruin us.”

“Does not the yhiabid us accept things only within the limits of our own natures?”

“It is impossible to do otherwise, Methi.”

“And therefore does not nature sometimes command us to resist?”

“It has been so reasoned, Methi, although not all the College is in agreement on that.”

“And if we resist fate, we must perish?”

“That is doubtless so, Methi.”

“And someday it might be our fate to perish?”

“That is possible, Methi.”

She slammed her hand down on the arm of her chair. “I refuse to bow to such a possibility. I refuse to perish, priest, or to lead men to perish. In sum, the College does not know the answer.”

“No, Methi, we must admit we do not.”

“I have a certain spiritual authority myself.”

“You are the viceroy of Phan on earth.”

“Will the priests respect that?”

“The priests,” said the old man, “are not anxious to have this matter cast back into their hands. They will welcome your intervention in the matter of the origin of humans, Methi.”

“It is,” she said, “dangerous to the people that such thoughts as these be heard outside this room. You will not repeat the reasoning we have made together. On your life, priest, and on your soul, you will not repeat what I have said to you.”

The old priest turned his head and gave Kurt a furtive, troubled look. “Let the Methi be gracious: this being is not deserving of punishment for any wrong.”

“He invaded the Rhmeiof Man.”

“He sought sanctuary.”

“Did you give it?”

“No,” the priest admitted.

“That is well,” said Ylith. “You are dismissed, priest.”

The old man made a deeper bow and withdrew, backing away. The heavy tread and metal clash of armed men accompanied the opening of the door: and the armed men remained after it was closed. Kurt heard and knew they were there, but he must not turn to look: time was short. He did not want to hasten it. The Methi still looked down on him, the tiny chains swaying, her dark face soberly thoughtful.

“You create difficulties wherever you go,” she said softly.

“Where is Kta, Methi? They would not tell me. Where is he?”

“They returned him to us a day ago.”

“Is he—?”

“I have not given sentence.” She said it with a shrug, then bent those dark eyes full upon him. “I do not really wish to kill him. He could be valuable to me. He knows it. I could hold him up to the other Indras-descended of Nephane and say: look, we are merciful, we are forgiving, we are your people. Do not fight against us.”

Kurt looked up at her, for a moment lost in that dark gaze, believing as many a hearer would believe Ylith t’Erinas: hope rose irrationally in him, on the tone of her gentle voice, her skill to reach for the greatest hopes. And good or evil, he did not know clearly which she was.

She was not like Djan, familiar and human and wielding power like a general. Ylith was a Methi as the office must have been: a goddess-on-earth, doing things for a goddess’ reasons and with amoral morality, creating truth.

Rewriting things as they should be.

He felt an awe of her that he had felt of nothing mortal, believed indeed that she could erase the both of them as if they had never been. He had been within the Rhmeiof Man, had been beside the fire: the skin on his arms was still painful. When Ylith spoke to him he felt the roaring silence of that fire drowning him.

He was fevered. He was fatigued. He saw the signs in himself, and feared instead his own weakness.

“Kta would be valuable to you,” he said, “even unwilling.” He felt guilty, knowing Kta’s stubborn pride. “Elas was the victim of one Methi; it would impress Nephane’s families if another Methi showed him mercy.”

“You have a certain logic on your side. And what of you? What shall I do with you?”

“I am willing to live,” he said.

She smiled that goddess-smile at him, her eyes alone alive. “You existence is a trouble; but if I am rid of you, it will not solve matters. You would still have existed. What should I write at your death? That this day we destroyed a creature which could not possibly exist, and so restored order to the universe?”

“Some,” he said, “are urging you to do that.”

She leaned back, curling her bejeweled fingers about the carved fishes of the chair arms. “If, on the other hand, we admit you exist, then where do you exist? We have always despised the Sufaki for accepting humans and nemet as one state: herein began the heresies with which they pervert pure religion, heresies which we will not tolerate.”

“Will you kill them? That will not change them.”

“Heresy may not live. If we believed otherwise, we should deny our own religion.”

“They have not crossed the sea to trouble you.”

Ylith’s hand came down sharply on the chair arm. “You are treading near the brink, human.”

Kurt bowed his head.

“You are ignorant,” she said. “This is understandable. I know of report that Djan-methi is—highly approachable. I have warned you before. I am not as she is.”

“I ask you—to listen. Just for a moment,—to listen.”

“First convince me that you are wise in nemet affairs.”

He bowed his head once more, unwilling to dispute with her to no advantage.

“What,” she said after a moment, “would you have to say that is worth my time? You have my attention, briefly. Speak.”

“Methi,” he said quietly, “what I would have said, were answers to questions your priests did not know how to ask me. My people are very old now, thousands and thousands of years of mistakes behind us that you do not have to make. But maybe I am wrong, maybe it is—what you call yhia,that I have intruded where I have no business to be and you will not listen because you cannot listen. But I could tell you more than you want to hear, I could tell you the future, where your precious little war with Nephane could lead you. I could tell you that my native world does not exist any longer, that Djan’s does not,—all for a war grown so large and so long that it ruins whole worlds as yours sinks ships.”

“You blaspheme!”

He had begun; she wished him silent. He poured out what he had to say in a rush, though guards ran for him.

“If you kill every last Sufaki you will still find differences to fight over. You will run out of people on this earth before you run out of differences.—Methi, listen to me! You know—if you have any sense you know what I am telling you. You can listen to me or you can do the whole thing over again, and your descendants will be sitting where I am.”

Lhe had him, dragged him backward, trying to force him to stand. Ylith was on her feet, beside her chair.

“Be silent!” Lhe hissed at him, his hard fingers clamped into Kurt’s arm.

“Take him from here,” said Ylith. “Put him with t’Elas. They are both mad. Let them comfort one another in their madness.”

“Methi,” Kurt cried.

Lhe had help now: they brought him to his feet, forced him from the hall and into the corridor, and there, finally, clear sense returned to him and he ceased to fight them.

“You were so near to life,” Lhe said.

“It is all right, t’Nethim,” Kurt said. “You will not be cheated.”

They went back to the upper prisons. Kurt knew the way, and, when they had come to the proper door, Lhe dismissed the reluctant guards out of earshot. “You are truly mad,” he said, fitting the key in the lock. “Both of you. She would give t’Elas honor, which he refuses. He has attempted suicide: we had to prevent him. It was our duty to do this. He was being taken from the temple: he meant to cast himself to the pavement, but we pushed him back, so that he fell instead on the steps. We have provided comforts, which he will not use.”

He dared look Lhe in the eyes, saw both anger and trouble there. Lhe t’Nethim was asking something of him: for a moment he was not sure what, and then he thought that the Methi would not be pleased if Kta evaded her justice. Elas had once hazarded its honor and its existence on receiving a prisoner in trust: and had lost. Methi’s law. Elas had risked it because of a promise unwittingly false.

Nethim was involved: the priest had said it. The honor of Nethim was in grave danger. Both Elas and the Methi had touched it.

The door opened. Lhe gestured him to go in, and locked the door behind him.

There were two cots within, a table, beneath a high barred window. Kta lay fully clothed, covered with dust and dried blood. They had brought him back the day before; in all that time, they had not cared for him, nor he for himself. Kurt exploded inwardly with fury at all nemet, even with Kta.

“Kta.” Kurt bent over him, and saw Kta blink and stare chillingly nothingward. There was vacancy there. Kurt did not ask consent: he went to the table where there was the usual washing bowl and urn. Clean clothes were laid there, and cloths, and a flask of telise.Lhe had not lied. It was Kta’s choice.

Kurt spread everything on the floor beside Kta’s cot, unstopped the teliseand slipped his arm beneath Kta’s head, putting the flask to his lips.

Kta swallowed a little of the potent liquid, choked over it and swallowed again. Kurt stopped the flask and set it aside, then soaked a cloth in water and began to wipe the mingled sweat and blood and dirt off the nemet’s face. Kta shivered when the cloth touched his neck; the water was cold.

“Kta,” said Kurt, “what happened?”

“Nothing,” said the nemet, not even looking at him. “They brought—they brought me back—”

Kurt regarded him sorrowfully. “Listen, friend, I am trying as best I know. But if you need better care, if there are things broken, tell me. They will send for it. I will ask them for it.”

“They are only scratches.” The threat of outsiders seemed to lend Kta strength. He struggled to rise, leaning on an elbow that was painfully torn. Kurt helped him. The telisewas having effect, although the sense of well-being would be brief, Kta did not move as if he was seriously hurt. Kurt put a pillow into place at the corner of the wall, and Kta leaned back on it with a grimace and a sigh,—looked down at his badly lacerated knee and shin, flexed the knee experimentally.

“I fell,” Kta said.

“So I heard.” Kurt refolded the stained cloth and started blotting at the dirt on the injured knee.

It needed some time to clean the day-old injuries, and necessarily it hurt. From time to time Kurt insisted Kta take a sip of telise,though it was only toward the end that Kta evidenced any great discomfort. Through it all Kta spoke little. When the injuries were clean and there was nothing more to be done, Kurt sat and looked at him helplessly. In Kta’s face the fatigue was evident. It seemed far more than sleeplessness or wounds,—something inward and deadly.

Kurt settled him flat again with a pillow under his head. Considering that he himself had been without sleep the better part of three days, he thought that weariness might be a major part of it: but Kta’s eyes were fixed again on infinity.

“Kta.”

The nemet did not respond and Kurt shook him. Kta did no more than blink.

“Kta, you heard me and I know it. Stop this and look at me. Who are you punishing? Me?”

There was no response, and Kurt struck Kta’s face lightly, then enough that it would sting. Kta’s lips trembled and Kurt looked at him in instant remorse, for it was as if he had added the little burden more than the nemet could bear. The threatened collapse terrified him.

Tired beyond endurance, Kurt sank down on his heels and looked at Kta helplessly. He wanted to go over to his own cot and sleep, he could not think any longer, except that Kta wanted to die and that he did not know what to do.

“Kurt.” The voice was weak, so distant Kta’s lips hardly seemed to move.

“Tell me how to help you.”

Kta blinked, turned his head, seeming for the moment to have his mind focused. “Kurt,—my friend, they—”

“What have they done, Kta? What did they do?”

“They want my help and—if I will not,—I lose my life, my soul. She will curse me from the earth,—to the old gods—the—” He choked, shut his eyes and forced a calm over himself that was more like Kta. “I am afraid, my friend, mortally afraid. For all eternity,—But how can I do what she asks?”

“What difference can your help make against Nephane?” Kurt asked. “Man, what pitiful little difference can it make one way or the other? Djan has weapons enough; Ylith has ships enough. Let others settle it. What are you? She has offered you life and your freedom, and that is better than you had of Djan.”

“I could not accept Djan-methi’s conditions either.”

“Is it worth this, Kta? Look at you! Look at you, and tell me it is worth it. Listen, I would not blame you; all Nephane knows how you were treated there. Who in Nephane would blame you if you turned to Indresul?”

“I will not hear your arguments,” Kta cried.

“They are sensible.” Kurt seized his arm and kept him from turning his face to the wall again. “They are sensible arguments, Kta, and you know it.”

“I do not understand reason any longer. The temple and the Methi will condemn my soul for doing what I know is right. Kurt, I could understand dying, but this—this is not justice. How can a reasonable heaven put a man to a choice like this?”

“Just do what they want, Kta. It doesn’t cost anyone much, and if you are only alive, you can worry about the right and the wrong of it later.”

“I should have died with my ship,” the nemet murmured. “That is where I was wrong. Heaven gave me the chance to die—in Nephane, in the camp of the Tamurlin, with Tavi.I would have peace and honor then. But there was always you. You are the disruption in my fate. Or its agent. You are always there—to make the difference.”

Kurt found his hand trembling as he adjusted the blanket over the raving nemet, trying to soothe him, taking for nothing the words that hurt. “Please,” he said. “Rest, Kta.”

“Not your fault. It is possible to reason—One must always reason—to know—”

“Be still.”

“If,” Kta persisted with fevered intensity, “if—I had died in Nephane with my father, then my friends, my crew—would have avenged me. Is that not so?”

“Yes,” Kurt conceded, reckoning the temper of men like Val and Tkel and their company. “Yes, they would have killed Shan t’Tefur.”

“And that,” said Kta, “would have cast Nephane into chaos, and they would have died, and come to join Elas in the shadows. Now they are dead,—as they would have died—but I am alive. Now I, Elas—”

“Rest. Stop this.”

“—Elas was shaped to the ruin of Nephane—to bring down the city in its fall. I am the last of Elas. If I had died before this I would have died innocent of my city’s blood. The crime would have been on Djan-methi’s hands. Then my soul would have had rest with theirs, whatever became of Nephane. Instead, I lived,—and for that I deserve to be where I am.”

“Kta,—hush. Sleep. You have a belly full of teliseand no food to settle it. It has unbalanced your mind. Please. Rest.”

“It is true,” said Kta, “I was born to ruin my people. It is just—what they try to make me do—”

“Blame me for it,” said Kurt. “I had rather hear that than this sick rambling. Answer me what I am, or admit that you cannot foretell the future.”

“It is logical,” said Kta, “that human fate brought you here to deal with human fate.”

“You are drunk, Kta.”

“You came for Djan-methi,” said Kta. “You are for her.”

Kta’s dark eyes closed—rolled back, helplessly. Kurt moved at last, realizing the knot at his belly, the sickly gathering of fear, dread of Guardians and Ancestors and the nemets reasoning.

Kta at last slept. For a long time Kurt stood staring down at him, then went to his own side of the room and lay down upon the cot, not to sleep, not daring to, only to rest his aching back. He feared to leave Kta unwatched, but at some time his eyes grew heavy, and he closed them only for a moment.

He jerked awake, panicked by a sound and simultaneously by the realization that he had slept.

The room was almost in darkness, but the faintest light came from the barred window over the table. Kta was on his feet, naked despite the chill, and had set the water bucket on the table, standing where a channel in the stone floor made a drain beneath the wall, beginning to wash himself.

Kurt looked to the window, amazed to find the light was that of dawn. That Kta had become concerned about his appearance seemed a good sign. Methodically Kta dipped up water and washed, and when he had done what he could by that means, he took the bucket and poured water slowly over himself, letting it complete the task.

Then he returned to his cot and wrapped in the blanket. He leaned against the wall, eyes closed, lips moving silently. Gradually he slipped into the state of meditation and rested unmoving, the morning sun beginning to bring detail to his face. He looked at peace, and remained so for about half an hour.

The day broke full, a shaft of light finding its way through the barred window. Kurt bestirred himself and straightened his clothing that his restless sleeping had twisted in knots.

Kta rose and dressed also, in his own hard-used clothing, refusing the Methi’s gifts. He looked in Kurt’s direction with a bleak and yet reassuring smile.