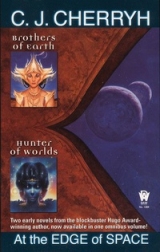

Текст книги "At the Edge of Space (Brothers of Worlds; Hunter of Worlds)"

Автор книги: C. J. Cherryh

Жанр:

Космическая фантастика

сообщить о нарушении

Текущая страница: 3 (всего у книги 36 страниц)

Yr, earth-snake, mother of all beasts.

The council of gods in heaven made Aem and Ti to die,

and dying, they brought forth children, man and woman.

“I have never tried to think it in human terms,” said Kta, frowning. “It is very hard.”

But with a gesture Kurt urged him, and Kta touched the strings again, trying, greatly frustrated.

“The first beings that were mortal were Nem and Panet, man and woman, twins. They sinned the great sin too. The council of gods rejected them for immortality because of it, and made their lives short. Phan especially hated them, and he mated with Yr the snake, and brought beasts and terrible things into the world to hunt man.

The Phan’s sister Qas defied his anger,

stole fire, rained down lightning on the earth.

Men took fire and killed Yr’s beasts, built cities.

Ten times a thousand years came and passed away.

Men grew many and kings grew proud,

sons of men and Yr the earth-snake,

sons of men and inim that ride the winds.

Men worshiped these half-men, the godkings.

Men did them honor, built them cities.

Men forgot the first gods,

and men’s works were foul.

“Then a prophecy came,” said Kta, “and Phan chose Isoi, a mortal woman, and gave her a half-god son: Qavur, who carried the weapons of Phan to destroy the world by burning. Qavur destroyed the godkings, but Isoi his mother begged him not to kill the rest of man, and he didn’t. Then Phan with his sword of plague came down and destroyed all men, but when he came to Isoi she ran to her hearthfire and sat down beside it, so that she claimed the gods’ protection. Her tears made Phan pity her. He gave her another son, Isem, who was husband of Nae the seagoddess and father of all men that sail on the sea. But Phan took Qavur to be immortal; he is the star that shines in morning, the messenger of the sun.

“But to keep Nae’s children from doing wrong, Phan gave Qavur the yhiato take to men. All law comes from it. From it we know our place in the universe. Anything higher is gods’ law; but that is beyond the words of the song. The song is the Ind.It is sacred to us. My father taught it to me, and the seven verses of it that are only for Elas. So it has come to us in each generation.”

“You said once,” said Kurt, “that you didn’t know whether I was man or not. Have you decided yet?”

Kta thoughtfully laid aside the aos,stilled its strings. “Perhaps,” said Kta, “some of the children of Nem escaped the plague; but you are not nemet. Perhaps instead you are descended of Yr, and you were set out among the stars on some world of Thael’s kindred. From what I have heard among humans, the earth seems to have had many brothers. But I don’t think you think so.”

“I said nothing.”

“Your look did not agree.”

“I wouldn’t distress you,” said Kurt, “by saying I consider you human.”

The nemet’s lips opened instantly, his eyes mirroring shock. Then he looked as if he suspected Kurt of some levity, and again, as if he feared he were serious. Slowly his expression took on a certain thoughtfulness, and he made a gesture of rejection.

“Please,” said Kta, “don’t say that freely.”

Kurt bowed his head then in respect to Kta, for the nemet truly looked frightened.

“I have spoken to the Guardians of Elas for you,” said Kta. “You are a disturbance here, but I do not feel that you are unwelcome with our Ancestors.”

Kurt dressed carefully upon the last morning. He would have worn the clothes in which he had come, but Mim had taken those away, unworthy, she had said, of the guest of Elas. Instead he had an array of fine clothing he thought must be Kta’s, and on this morning he chose the warmest and most durable, for he did not know what the day might bring him, and the night winds were chill. So it was cold in the rooms of the Afen, and he feared he would not leave it once he entered.

Elas again began to seem distant to him, and the sterile modernity of the center of the Afen increasingly crowded upon his thoughts, the remembrance that, whatever had happened in Elas, his business was with Djan and not with the nemet.

He had chosen his option at the beginning of the two weeks, in the form of a small dragon-hilted blade from among Kta’s papers, where it had been gathering dust and would not be missed.

He drew it now from its hiding place and considered it, apt either for Djan or for himself.

And fatally traceable to the house of Elas.

It did not go within his clothing, as he had always meant to carry it. Instead he laid it aside on the dressing table. It would go back to Kta. The nemet would be angry at the theft, but it would make amends, all the same.

Kurt finished dressing, fastening the ctan,the outer cloak, upon his shoulder, and chose a bronze pin with which to do it, for his debts to Elas were enough, he would not use the ones of silver and gold which he had been provided.

A light tapping came at the door, Mim’s knock.

“Come in,” he bade her, and she quietly did so. Linens were changed daily throughout the house. She carried fresh ones, for bed and for bath, and she bowed to him before she set them down to begin her work. Of late there was no longer hate in Mim’s look: he understood that she had had cause, having been prisoner of the Tamurlin; but she had ceased her war with him of her own accord, and in consideration of that he always tried especially to please Mim.

“At least,” he observed, “you will have less washing in the house hereafter.”

She did not appreciate the poor humor. She looked at him, then lowered her eyes and turned around to tend her business.

And froze, with her back to him, facing the dresser. Hesitantly she reached for the knife, snatched at it and faced about again as if uncertain that he would not pounce on her. Her dark eyes were large with terror; her attitude was that of one determined to resist if he attempted to take it from her.

“Lord Kta did not give you this,” she said.

“No,” he said, “but you may give it back to him.”

She clasped it in both hands and continued to stare at him. “If you bring a weapon into the Afen you kill us, Kurt-ifhan. All Elas would die.”

“I have given it back,” he said. “I am not armed, Mim. That is the truth.”

She slipped it into the belt beneath her overskirt, through one of the four slits that exposed the filmy pelanfrom waist to toe, patted it flat. She was so small a woman: she had a tiny waist, a slender neck accentuated by the way she wore her hair in many tiny braids coiled and clustered above the ears. So little a creature, so soft-spoken, and yet he was continually in awe of Mim, feeling her disapproval of him in every line of her stiff little back.

For once, as in the rhmeithat night, there was something like distress, even tenderness in the way she looked at him.

“Kta wishes you come back to Elas,” she said.

“I doubt I will be allowed to,” he said.

“Then why would the Methi send you here?”

“I don’t know. Perhaps to satisfy Kta for a time. Perhaps so I’ll find the Afen the worse by comparison.”

“Kta will not let harm come to you.”

“Kta had better stay out of it. Tell him so, Mim. He could make the Methi his enemy that way. He had better forget it.”

He was afraid. He had lived with that nagging fear from the beginning, and now that Mim touched nerves, he found it difficult to speak with the calm that the nemet called dignity. The unsteadiness of his voice made him greatly ashamed.

And Mim’s eyes inexplicably filled with tears—fierce little Mim, unhuman Mim, that he could have thought interestingly female to Kurt but for her alien face. He did not know if any other being would ever care enough to cry over him, and suddenly leaving Elas was unbearable.

He took her slim golden hands in his, knew at once he should not have, for she was nemet and she shivered at the very touch of him. But she looked up at him and did not show offense. Her hands pressed his very gently in return.

“Kurt-ifhan,” she said, “I will tell lord Kta what you say, because it is good advice. But I don’t think he will listen to me. Elas will speak for you. I am sure of it. The Methi has listened before to Elas. She knows that we speak with the power of the Families. Please go to breakfast. I have made you late. I am sorry.”

He nodded and started to the door, looked back again. “Mim,” he said, because he wanted her to look up. He wanted her face to think of, as he wanted everything in Elas fixed in his mind. But then he was embarrassed, for he could think of nothing to say.

“Thank you,” he murmured, and quickly left.

4

All the way to Afen, Kurt had balanced his chances of rounding on his three nemet guards and making good his escape. The streets of Nephane were twisting and torturous, and if he could remain free until dark, he thought, he might possibly find a way out into the fields and forests.

But Nym himself had given him into the hands of the guards and evidently charged them to treat him well, for they showed him the greatest courtesy. Elas continued to support him, and for the sake of Elas, he dared not do what his own instincts screamed to do: to run,—to kill if need be.

They passed into the cold halls of the Afen itself and it was too late. The stairs led them up to the third level, that of the Methi.

Djan waited for him alone in the modern hall, wearing the modest chatemand pelanof a nemet lady, her auburn hair braided at the crown of her head, laced with gold.

She dismissed the guards, then turned to him. It was strange, as she had foretold,—to see a human face after so long among the nemet. He began to understand what it had been for her, alone, slipping gradually from human reality into nemet. He noticed things about human faces he had never seen before, how curiously level the planes of the face, how pale her eyes, how metal-bright her hair. The war, the enmity between them—even these seemed for the moment welcome, part of a familiar frame of reference. Elas faded in this place of metal and synthetics.

He fought it back into focus.

“Welcome back,” she bade him, and sank into the nearest chair, gestured him welcome to the other. “Elas wants you,” she advised him then. “I am impressed.”

“And I,” he said, “would like to go back to Elas.”

“I did not promise that,” she said. “But your presence there has not proved particularly troublesome.” She rose again abruptly, went to the cabinet against the near wall, opened it. “Care for a drink, Mr. Morgan?”

“Anything,” he said, “thank you.”

She poured them each a little glass and brought one to him. It was telise.She sat down again, leaned back and sipped at her own. “Let me make a few points clear to you,” she said. “First: this is my city; I intend it should remain so. Second: this is a nemet city, and that will remain so too. Our species has had its chance. It’s finished. We’ve done it. Pylos, my world Aeolus—both cinders. It’s insane. I spend these last months waiting to die for not following orders, wondering what would become of the nemet when the probe ship returned with the authority and the firepower to deal with me. So I don’t mourn them much. I—regret Aeolus. But your intervention was timely, for the nemet. That does not mean,” she added, “that I have overwhelming gratitude to you.”

“It does not make sense,” he said, “that we two should carry on the war here. There’s nothing either of us has to win.”

“Is it required,” she asked, “that a war make sense? Consider ours: we’ve been at it two thousand years. Probably everything your side and mine says about its beginning is a lie. That hardly matters. There’s only the now,and the war feeds on its own casualties. And we approach our natural limits. We started out destroying ships in one little system, now we destroy worlds. Worlds. We leave dead space behind us. We count casualties by zones. We Hanan—we never were as numerous or as prolific as you; we can’t produce soldiers fast enough to replace the dead. Embryonics, lab-born soldiers, engineered officers, engineered followers—our last hope. And you killed it. I will tell you, my friend, something I would be willing to wager your Alliance never told you: you just stepped up the war by what you did at Aeolus. I think you made a great miscalculation.”

“Meaning what?”

“Aeolus was the center, the great center of the embryonics projects. Billions died in its laboratories. The workers, the facilities, the records—irreplaceable. You have hurt us too much. The Hanan will cease to restrict targets altogether now. The final insanity, that is what I fear you have loosed on humanity. I do much fear. And we richly deserve it, the whole human race.”

“I don’t think,” he said, for she disturbed his peace of mind, “that you enjoy isolation half as much as you pretend.”

“I am Aeolid,” she said. “Think about it.”

It took a moment. Then the realization set in, and revulsion, gut-deep: of all things Hanan that he loathed, the labs were the most hateful.

Djan smiled. “Oh, I’m human, of human cells. And superior—I would have been destroyed otherwise; efficiently engineered—for intelligence, and trained to serve the state. My intelligence then advised me that I was being used, and I disliked that. So I found my moment and turned on the state.” She finished the drink and set it aside. “But you wouldn’t like separation from humanity. Good. That may keep you from trying to cut my throat.”

“Am I free to leave, then?”

“Not so easily, not so easily. I had considered perhaps giving you quarters in the Afen. There are rooms upstairs, only accessible from here. In such isolation you could do no possible harm. Instinct—something—says that would be the best way to dispose of you.”

“Please,” he said, rationally, shamelessly, for he had long since made up his mind that he had nothing to gain in Nephane by antagonizing Djan. “If Elas will have me, let me go back there.”

“In a few days I will consider that. I only want you to know your alternatives.”

“And what until then?”

“You’re going to learn the nemet language. I have things all ready for you.”

“No,” he said instantly. “No. I don’t need any mechanical helps.”

“I am a medic, among other things. I’ve never known the teaching apparatus abused without it doing permanent damage. No. Ruining the mind of the only other human accessible would be a waste. I shall merely allow you access to the apparatus and you may choose your own rate.”

“Then why do you insist?”

“Because your objection creates an unnecessary problem for you, which I insist be solved. I am giving you a chance to live outside. So I make it a fair chance, an honest chance; I wish you success. I no longer serve the purposes of the Hanan; I refuse to be programmed into a course of action I do not choose. And likewise, if it becomes clear to me that you are becoming a nuisance to me, don’t think you can plead ignorance and evade the consequences. I am removing your excuses, you see. And if I must, I will call you in or kill you. Don’t doubt it for a moment.”

“It is,” he said, “a fairer attitude than I would have expected of you. I would be easier in my mind if I understood you.”

“All my motives are selfish,” she said. “At least in the sense that all I do serves my own purposes. If I once perceive you are working against those purposes, you are done. If I perceive that you are compatible with them, you will find no difficulty. I think that is as clear as I can make it, Mr. Morgan.”

5

Kta was not in the rhmeias Kurt had expected him to be when he reached the safety of Elas. Hef was, and Mim. Mim scurried upstairs ahead of him to open the window and air the room, and she spun about again when she had done so, her dark eyes shining.

“We are so happy,” she said, in human speech. The machine’s reflex pained him, punishing understanding.

It was all Mim had time to say, for there was Kta’s step upon the landing, and Mim bowed and slipped out as Kta came in.

“Much crying in our house these days,” said Kta, casting a look after Mim’s retreat down the stairs. Then he looked at Kurt, smiled a little. “But no more. EiKurt, sit, sit, please. You look like a man three days drowned.”

Kurt ran his hand through his hair and fell into a chair. His limbs were shaking. His hands were white. “Speak Nechai,” he said. “It’s easier.”

Kta blinked, looked him over. “How is this?” he asked, and there was unwelcome suspicion in his voice.

“Trust me,” Kurt said hoarsely. “The Methi has machines that can do this. I would not lie to you.”

“You are pale,” said Kta. “You are shaking. Are you hurt?”

“Tired,” he said. “Kta,—thank you, thank you for taking me back.”

Kta bowed a little. “Even my honored father came and spoke for you, and never in all the years of our house has Elas done such a thing. But you are of Elas. We are glad to receive you.”

“Thank you.”

He rose and attempted a bow. He had to catch at the table to avoid losing his balance. He made it to the bed and sprawled. His memory ceased before he had stopped moving.

Something tugged at his ankle. He thought he had fallen into the sea and something was pulling him down. But he could not summon the strength to move.

Then the ankle came free and cold air hit his foot. He opened his eyes on Mim, who began to remove the other sandal. He was lying on his own bed, fully clothed, and cold. Outside the window it was night. His legs were like ice, his arms likewise.

Mim’s dark eyes looked up, realized that he was awake. “Kta takes bad care for you,” she said, “leaving you so. You have not moved. You sleep like the dead.”

“Speak Nechai,” he asked of her. “I have been taught.”

Her look was briefly startled. Then she accepted human strangeness with a little bow, wiped her hands on her chatemand dragged at the bedding to cover him, pulling the bedclothes from beneath him, half-asleep as he was.

“I am sorry,” she said. “I tried not to wake you, but the night was cold and my lord Kta had left the window open and the light burning.”

He sighed deeply and reached for her hand as it drew the coverlet across him. “Mim,—”

“Please.” She evaded his hand, slipped the pin from his shoulder and hauled the tangled ctanfrom beneath him, jerked the catch of his wide belt free, then drew the covers up to his chin.

“You will sleep easier now,” she said.

He reached for her hand again, preventing her going. “Mim, what time is it?”

“Late,—late.” She pulled, but he did not let her go, and she glanced down, her lashes dark against her bronze cheeks. “Please, please let me go, lord Kurt.”

“I asked Djan, asked her to send you word—so you would not worry.”

“Word came. We did not know how to understand it. It was only that you were safe. Only that.” She pulled again. “Please.”

Her lips trembled, and eyes were terrified, and when he let her hand go she spun around and fled to the door. She hardly paused to close it, her slippered feet pattering away down the stairs at breakneck speed.

If he had had the strength he would have risen and gone after her, for he had not meant to hurt Mim on the very night of his return. He lay awake and was angry, at nemet custom and at himself, but his head hurt abominably and made him dizzy. He sank into the soft down and slipped away. There was tomorrow. Mim would have gone to bed too, and he would scandalize the house by trying to speak to her tonight.

The morning began with tea, but there was no Mim, cheerily bustling in with morning linens and disarranging things. She did appear in the rhmeito serve, but she kept her eyes down when she poured for him.

“Mim,” he whispered at her, and she spilled a few drops, which burned, and moved quickly to pour for Kta. She spilled even his, at which the dignified nemet shook his burned hand and looked up wonderingly at the girl, but said nothing.

There had been the usual round of formalities, and Kurt had bowed deeply before Nym and Ptas and Aimu, and thanked the lord of Elas in his own language for his intercession with Djan.

“You speak very well,” Nym observed by way of acknowledging him; and Kurt realized he should have explained through Kta. An elder nemet cherished his dignity, and Kurt saw that he must have mightily offended lord Nym with his human sense of the dramatic.

“Sir,” said Kurt, “you honor me. By machines I do this. I speak slowly yet and not well, but I do recognize what is said to me. When I have listened a few days, I will be a better speaker. Forgive me if I have offended you. I was so tired yesterday I had no sense left to explain where I have been or why.”

The honorable Nym considered, and then the faintest of smiles touched his face, growing to an expression of positive amusement. He touched his laced fingers to his breast and inclined his head, apology for laughter.

“Welcome a second time to Elas, friend of my son. You bring gladness with you. There are smiles on faces this morning, and there were few the days we were in fear for you. Just when we thought we had comprehended humans, here are more wonders,—and what a relief to be able to talk without waiting for translations!”

So they were settled together, the ritual of tea begun. Lady Ptas sat enthroned in their center, a comfortable woman. Somehow when Kurt thought of Elas, Ptas always came first to mind,—a gentle and dignified lady with graying hair, the very heart of the family, which among nemet a mother was: Nym’s lady, source of life and love, protectress of his ancestral religion. Into a wife’s hands a man committed his hearth, and into a daughter-in-law’s hands—his hope of a continuing eternity. Kurt began to understand why fathers chose their sons’ mates; and considering the affection that was evident between Nym and Ptas, he could no longer think such marriages were loveless. It was right, it was proper, and he sat cross-legged upon a fleece rug, equal to Kta, a son of the house, drinking the strong sweetened tea and feeling that he had come home indeed.

And after tea lady Ptas rose and bowed formally before the hearthfire, lifting her palms to it. Everyone stood in respect, and her sweet voice called upon the Guardians.

“Ancestors of Elas, upon this shore and the other of the Dividing Sea, look kindly upon us. Kurt t’Morgan has come back to us. Peace be between the guest of our home and the Guardians of Elas. Peace be among us.”

Kurt was greatly touched, and bowed deeply to lady Ptas when she was done.

“Lady Ptas,” he said, “I honor you very much.” He would have said—like a son, but he would not inflict that doubtful compliment on the nemet lady.

She smiled at him with the affection she gave her children; and from that moment, Ptas had his heart.

“Kurt,” said Kta when they were alone in the hall after breakfast, “my father bids you stay as long as it pleases you. This he asked me to tell you. He would not burden you with giving answer on the instant, but he would have you know this.”

“He is very kind,” said Kurt. “You have never owed me all of the things you have done for me. Your oath never bound you this far.”

“Those who share the hearth of EIas,” said Kta, “have been few, but we never forget them. We call this guest-friendship. It binds your house and mine for all time. It can never be broken.”

He spent the days much in Kta’s company within Elas, talking, resting, enjoying the sun in the inner court of the house where there was a small garden.

One thing remained to trouble him: Mim was usually absent. She no longer came to his rooms when he was there. No matter how he varied his schedule, she would not come; he only found his bed changed about when he would return after some absence. When he hovered about the places where she usually worked, she was simply not to be found.

“She is at market,” Hef informed him on a morning that he finally gathered his courage to ask.

“She has not been much about lately,” Kurt observed.

Hef shrugged. “No, lord Kurt. She has not.”

And the old man looked at him strangely, as if Kurt’s anxiety had undermined the peace of his morning too.

He became the more determined. When he heard the front door close at noon, he sprang up to run downstairs but he had only a glimpse of her hurrying by the opposite hall into the ladies’ quarters behind the rhmei.That was Ptas’ territory, and no man but Nym could set foot there.

He walked disconsolately back to the garden and sat in the sun, staring at nothing in particular and tracing idle patterns in the pale dust.

He had hurt her. Mim had not told the matter to anyone, he was sure, for if she had he had no doubt he would have had Kta to deal with.

He wished desperately that he could ask someone how to apologize to her, but it was not something he could ask of Kta, or of Hef; and certainly he dared ask no one else.

She served at dinner that night, as at every meal, and still avoided his eyes. He dared not say anything to her. Kta was sitting beside him.

Late that night he set himself in the hall and doggedly waited, far past the hour when the family was decently in bed, for the chanof Elas had as her last duties to set out things for breakfast tea and to extinguish the hall lights as she retired to bed.

She saw him there, blocking her way to her rooms. For a moment he feared she would cry out; her hand flew to her lips. But she stood her ground, still looking poised to run.

“Mim. Please. I want to talk with you.”

“I do not want to talk with you. Let me pass.”

“Please.”

“Do not touch me. Let me pass. Do you want to wake all the house?”

“Do that, if you like. But I will not let you go until you talk with me.”

Her eyes widened slightly. “Kta will not permit this.”

“There are no windows on the garden and we cannot be heard there. Come outside, Mim. I swear I want only to talk.”

She considered, her lovely face looking so frightened he hurt for her; but she yielded and walked ahead of him to the garden. The world’s moon cast dim shadows here. She stopped where the light was brightest, clasping her arms against the chill of the night.

“Mim,” he said, “I did not mean to frighten you that night. I meant no harm by it.”

“I should never have been there alone. It was my fault.—Please, lord Kurt, do not look at me that way. Let me go.”

“Because I am not nemet,—you felt free to come in and out of my room and not be ashamed with me. Was that it, Mim?”

“No.” Her teeth chattered so she could hardly talk, and the cold was not enough for that. He slipped the pin off his ctan,but she would not take it from him, flinching from the offered garment.

“Why can I not talk to you?” he asked. “How does a man ever talk to a nemet woman? I refrain from this, I refrain from that, I must not touch, must not look, must not think. How am I to—?”

“Please.”

“How am I to talk with you?”

“Lord Kurt, I have made you think I am a loose woman. I am chanto this house; I cannot dishonor it. Please let me go inside.”

A thought came to him. “Are you his?Are you Kta’s?”

“No,” she said.

Against her preference he took the ctanand draped it about her shoulders. She hugged it to her. He was near enough to have touched her. He did not, nor did she move back; he did not take that for invitation. He thought that whatever he did, she would not protest or raise the house. It would be trouble between her lord Kta and his guest, and he understood enough of nemet dignity to know that Mim would choose silence. She would yield, hating him.

He had no argument against that.

In sad defeat, he bowed a formal courtesy to her and turned away.

“Lord Kurt,” she whispered after him, distress in her voice.

He paused, looking back.

“My lord,—you do not understand.”

“I understand,” he said, “that I am human. I have offended you. I am sorry.”

“Nemet do not—” She broke off in great embarrassment, opened her hands, pleading. “My lord, seek a wife. My lord Nym will advise you. You have connections with the Methi and with Elas. You could marry,—easily you could marry, if Nym approached the right house—”

“And if it was you I wanted?”

She stood there, without words, until he came back to her and reached for her. Then she prevented him with her slim hands on his. “Please,” she said. “I have done wrong with you already.”

He ignored the protest of her hands and took her face between his palms ever so gently, fearing at each moment she would tear from him in horror. She did not. He bent and touched his lips to hers, delicately, almost chastely, for he thought the human custom might disgust or frighten her.

Her smooth hands still rested on his arms. The moon glistened on tears in her eyes when he drew back from her. “Lord,” she said, “I honor you. I would do what you wish, but it would shame Kta and it would shame my father and I cannot.”

“What can you?” He found his own breathing difficult. “Mim, what if some day I did decide to talk with your father? Is that the way things are done?”

“To marry?”

“Some day it might seem a good thing to do.”

She shivered in his hands. Tears spilled freely down her cheeks.

“Mim, will you give me yes or no? Is a human hard for you to look at? If you had rather not say, then just say ‘let me be’ and I will do my best after this not to bother you.”

“Lord Kurt, you do not know me.”

“Are you determined I will never know you?”

“You do not understand. I am not the daughter of Hef. If you ask him for me he must tell you, and then you will not want me.”

“It is nothing to me whose daughter you are.”

“My lord,—Elas knows. Elas knows. But you must listen to me now, listen. You know about the Tamurlin. I was taken when I was thirteen. For three years I was slave to them. Hef only calls me his daughter, and all Nephane thinks I am of this country. But I am not, Kurt. I am Indras, of Indresul. And they would kill me if they knew. Elas has kept this to itself. But you—you cannot bear such a trouble. People must not look at you and think Tamurlin: it would hurt you in this city; and when they see me, that is what they must think.”

“Do you believe,” he asked, “that what they think matters with me? I am human. They can see that.”

“Do you not understand, my lord? I have been property of every man in that village. Kta must tell you this if you ask Hef for me. I am not honorable. No one would marry Mim h’Elas. Do not shame yourself and Kta by making Kta say this to you.”

“After he had said it,” said Kurt, “would he give his consent?”