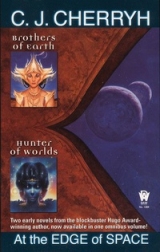

Текст книги "At the Edge of Space (Brothers of Worlds; Hunter of Worlds)"

Автор книги: C. J. Cherryh

Жанр:

Космическая фантастика

сообщить о нарушении

Текущая страница: 31 (всего у книги 36 страниц)

But reversing the proposition, to allow another to assume he had what he did not, that was chanokhia,a vaikkawith humor indeed, if it worked. It it did not—the loss must be reckoned proportional to the failure of gain.

Her eyes strayed to the clock. As another figure turned over, the last hour of the night had begun. Soon the morning hour would begin the last day of Tejef’s life, or of her own.

“Chimele,” said the voice from control: Raxomeqh, fourth of the Navigators. “Projection from Mijanothe.”

Predictable, if not predicted, Chimele sighed wearily and rose. “Accepted,” she said, and saw herself and her desk suddenly surrounded by the paredreof Mijanothe.She bowed respectfully before aged Thiane.

“Hail Thiane, venerable and honored among us.”

“Hail Ashanome,” said Thiane, leaning upon her staff, her eyes full of fire. “But do I hail you reckless or simply forgetful?”

“I am aware of the time, eldest of us all.”

“And I trust memory also has not failed you.”

“I am aware of your displeasure, reverend Thiane. So am I aware that the Orithanhe has given me this one more day, so despite your expressed wish, you have no power to order me otherwise.”

Thiane’s staff thudded against the carpeting. “You are risking somewhat more than my displeasure, Chimele. Destroy Priamos!”

“I have kamethi and nasithiwho must be evacuated. I estimate that as possible within the limit prescribed by the Orithanhe. I will comply with the terms of the original and proper decree at all deliberate speed.”

“There is no time for equivocation. Standing off to moonward is Tashavodh,if you have forgotten. I have restrained Kharxanen with difficulty from seeking a meeting with you at this moment.”

“I honor you for your wisdom, Thiane.”

“Destroy Priamos.”

“I will pursue my own course to the limit of the allotted time. Priamos will be destroyed or Tejef will be in our hands.”

“If,” said Thiane, “if you do this so that it seems vaikkaupon Tashavodh,then, Ashanome,run far, for I will either outlaw you, Chimele, and see you hunted to Tejef’s fate, or I will see the nasul Ashanomeitself hunted from star to star to all time. This I will do.”

“Neither will you do, Thiane, for if I am declared exile, I will seek out Tashavodhand kill Kharxanen and as many of his sraas I can reach when they take me aboard. I am sure he will oblige me.”

“Simplest of all to hear me and destroy Priamos. I am of many years and much travel, Chimele. I have seen the treasures of many worlds, and I know the value of life. But Priamos itself is not unique, not the sole repository of this species nor essential to the continuance of human culture. Our reports indicate even the human authorities abandoned it as unworthy of great risk in its defense. Need I remind you how far a conflict between Tashavodhand Ashanomecould spread, through how many star systems and at what hazard to our own species and life in general?”

“It is not solely in consideration of life on Priamos that I delay. It is my arastietheat stake. I have begun a vaikkaand I will finish it on my own terms.”

“Your m’melakhiais beyond limit. If your arastiethecan support such ambition, well; and if not, you will perish miserably, and your dynasty will perish with you. Ashanomewill become a whisper among the nasuli,a breath, a nothing.”

“I have told you my choice.”

“And I have told you mine. Hail Ashanome.I give you honor now. When next we meet, it may well be otherwise.”

“Hail Mijanothe,” said Chimele, and sank into her chair as the projection flicked out.

For a moment she remained so. Then with a steady voice she contacted Raxomeqh.

“Transmission to Weissmouth base two,” she directed, and the paredreof the lesser ship in Weissmouth came into being about her. Ashakh greeted her with a polite nod.

“Chaikhe is landing,” said Chimele, “but I forbid you to wait to meet her or to seek any contact with her.”

“Am I to know the reason?”

“In this matter, no. What is Aiela’s status?”

“Indeterminate. The amaut are searching street by street with considerable commotion. I have awaited your orders in this matter.”

“Arm yourself, locate Aiela, and go to him. Follow his advice.”

“Indeed,” Ashakh looked offended, as well he might. His arastiethehad grown troublesome in its intensity in the nasul:it had suffered considerably in her service already. She chose not to react to his recalcitrance now and his expression became instead bewildered.

“For this there is clear reason,” she told him. “Aiela’s thinking will not be predictable to an iduve, and yet there is chanokhiain that person. In what things honor permits, seek and follow this kameth’s advice.”

“I have never failed you in an order, Chimele-Orithain, even at disadvantage. But I protest Chaikhe’s being—”

She ignored him. “Can you sense whether Khasif or Mejakh is alive?”

“Regarding Mejakh, I—feel otherwise. Regarding Khasif, I think so; but I sense also a great wrongness. I am annoyed that I cannot be more specific. Something is amiss, either with Tejef or with Khasif. I cannot be sure with them.”

“They are both violent men. Their takkhenesis always perturbing. It will be strange to think of Mejakh as dead. She was always a great force in the nasul.”

“Have you regret?”

“No,” said Chimele. “But for Khasif, great regret. Hail Ashakh. May your eye be keen and your mind ours.”

“Hail Chimele. May the nasullive.”

He had given her, she knew as the projection went out, the salutation of one who might not return. A kameth would think it ill-omened. The iduve were not fatalists.

11

Isande came awake slowly, aware of aching limbs and the general disorientation caused by drugs in her system. Upon reflex she felt for Aiela, and knew at once that she did not lie upon the concrete at the port. She was concerned to know if she had all her limbs, for it had been a terrible explosion.

Isande.Aiela’s thoughts burst into hers with an outpouring of joy. Pain came, cold, darkness, and the chill of earth, but above all relief. He read her confusion and fired multilevel into her mind that she must be aboard Tejef’s ship, and that amaut treachery and human help had put her there. A shell had exploded near them. He was whole. Was she? And the others?

Under Aiela’s barrage of questions and information she brought her blurred vision to focus and acknowledged that indeed she did seem to be aboard a ship. Khasif and Mejakh—she did not know. No. Mejakh—dead, dead—a nightmare memory of the inside of an aircraft, Mejakh’s corpse a torn and bloody thing, the explosion nearest her.

Are you all right?Aiela persisted, trying to feel what she felt.

I believe so.She was numb. There was plasmic restruct on her right hand. The flesh was dark there. And hard upon that assessment came the realization that she, like Daniel, like Tejef, was trapped on the surface of Priamos. Aiela could be lifted offworld. She could not. Aiela would live. At least she had that to comfort her.

No!and with Aiela’s furious denial came a vision of sky with a horizon of jagged masonry, the cold cloudy light of stars overhead. He hurt, pain from cracking his head on the pavement, bruises and cuts beyond counting from clambering through the ruins to escape– Escape what? The ship inaccessible?Isande began to panic indeed; and he pleaded with her to stop, for her fear came to him, and he was so overwhelmingly tired.

Another presence filtered through his mind—Daniel. Although his thoughts reached to Weissmouth and back, he stood in a room not far away. A pale child—Arle, her image never before so clear—slept under sedation: he worried for her. And in that room was a woman whose name was Margaret, a poor, broken thing kept alive with tubings and life support. A dark man sat beside the woman, talking to her softly, and this was Tejef.

Rage burned through Isande, rejected instantly by Daniel: Murderer!she thought; but Daniel returned: At least this one cares for his people, and that is more than Chimele can do.

Blind!Isande cried at him, but Daniel would not believe it.

Chimele would be a target I would regret less.

And that disloyalty so upset Isande that she threw herself off the bed and staggered across the little room to try the door, cursing at the human the while in such thoughts as she did not use when her mind was whole.

I cannot reason with Daniel,said Aiela; but he knows the choice this world has and he will remember it when he must. Humans are like that.

Kill him,Isande raged at Daniel. You have the chance now: kill him, kill him, kill him!

Daniel foreknew defeat, weaponless as he was; and Isande grew more reasoning then and was sorry, for Daniel was as frightened as she and nearly as helpless. Yet Aiela was right: when the time came he would make one well-calculated effort. It was the reasonable thing to do, and that, he had learned of the iduve—to weigh things. But he resented it: Chimele had more power to choose alternatives than Tejef, and stubbornly refused to negotiate anything.

Iduve do not negotiate when they are winning or when they are losing.Isande flared back, hating that selective human blindness of his, that persistence in reckoning everyone as human; and that Tejef you honor so has already killed millions by his actions; by iduve reckoning, his was the action that began this. He knew what would happen when he sheltered here among humans.

Tejef has given us our lives,Daniel returned, with that reverence upon the word lifethat a kallia would spend upon giyre.Tejef was fighting for his own life, and that struck a response from the human at a primal level. Still Daniel would kill him. The contradictions so shocked Isande that she withdrew from that tangle of human logic and fiercely agreed that it would certainly be his proper giyreto his asuthi and Ashanometo do so.

The thought that echoed back almost wept. For Arle’s life, for this woman Margaret’s, for yours, for Aiela’s, I will try to kill him. I am afraid that I will kill him for my own—I am ashamed of that. And it is futile anyway.

You are not going to die,Aiela cast at them both, and the stars lurched in his vision and loose brick rattled underfoot as he hurled himself to his feet. I am going to do something. I don’t know what, but I’m going to try, if I can only get back to the civilized part of town.

Through his memory she read that he had been trying to do that for most of the night, and that he had been driven to earth by human searchers armed with lights, hovercraft thundering about the ruined streets, occasional shots streaking the dark. He was exhausted. His knees were torn from falling and felt unsure of his own weight. If called upon to run again he simply could not do it.

Try the ship,she pleaded with him. Chimele will want you back. Aiela, please—as long as you can hold open any communication between Daniel and myself—the revulsion crept through even at such a moment– we are a threat to Tejef.

Forget it. I can’t reach the port. They’re between me and there right now. But even if I do get help, all I want is an airship and a few of theokkitani-as. I’m going to come after you.

Simplest of all for me to tell Tejef where you are,she sent indignantly, and I’m sure he’d send a ship especially to transport you here. Oh, you are mad, Aiela!

One of Tejef’s ships is an option I’m prepared to take if all else fails.That was the cold stubbornness that was always his, world-born kallia, ignorant and smugly self-righteous; but she recognized a touch of humanity in it too, and blamed Daniel.

Aiela did not cut off that thought in time: it flowed to his asuthe. No,said Daniel, I’m afraid that trait must be kalliran, because I’ve already told him he’s insane. I can’t really blame him. He loves you. But I suppose you know that.

Daniel was not welcome in their privacy. She said so and then was sorry, for the human simply withdrew in sadness. In his way he loved her too, he sent, retreating, probably because he saw her with Aiela’s eyes, and Aiela’s was not capable of real malice, only of blindness.

Oh, blast you,she cried at the human, and hated herself.

Stop it,Aiela sent them both. You’re hurting me and you know it. Behave yourselves or I’ll shut you both out. And it’s lonely without you.

“Your asuthi,” asked Tejef, coming through Daniel’s contact. He had risen from Margaret’s side, for she slept again, and now the iduve looked on Daniel with a calculating frown. “Does that look of concentration mean you are receiving?”

“Aiela comes and goes in my mind,” said Daniel. Idiot,Aiela sent him: Don’t be clever with him.

“And I think that if Isande were conscious, you might know that too. Is she conscious, Daniel? She ought to be.”

“Yes, sir,” Daniel replied, feeling like a traitor. But Isande controlled the panic she felt and urged him to yield any truth he must: Daniel’s freedom and Tejef’s confidence that he would raise no hand to resist him were important. Iduve were unaccustomed to regard m’metaneias a threat: they were simply appropriated where found, and used.

Through Daniel’s eyes she saw Tejef leave the infirmary, his back receding down the corridor; she felt Daniel’s alarm, wishing the amaut were not watching him. Potential weapons surrounded him in the infirmary, but a human against an amaut’s strength was helpless. He dared go as far as the hall, closed the infirmary door behind him, watching Tejef.

Then came the audible give of the door lock and seal. Isande backed dizzily from the door, knocking into a table as she did so. Tejef was with her: his harachiafilled the little room, an indigo shadow over all her hazed vision. The force of him impressed a sense of helplessness she felt even more than Aiela’s frantic pleading in her mind.

“Isande,” said Tejef, and touched her. She cringed from his hand. His tone was friendly, as when last they had spoken, before Reha’s death. Tejef had always been the most unassuming of iduve, a gentle one, who had never harmed any kameth—save only Reha. Perhaps it did not even occur to him that a kameth could carry an anger so long. She hated him, not least of all for his not realizing he was hated.

“Are you in contact with your asuthi?” he asked her. “Which is yours? Daniel? Aiela?”

Admit the truth,Aiela sent. Admit to anything he asks.And when she still resisted: I’m staying with you, and if you make him resort to theidoikkhe, I’ll feel it too.

“Only to Aiela,” she replied.

“This kameth is not familiar to me.”

“I will not help you find him.”

A slight smile jerked at his mouth. “Your attitude is understandable. Probably I shall not have to ask you.”

“Where is Khasif?” Aiela prompted that question. She asked it.

The room winked out, and they were projected into the room that held Khasif. The iduve was abed, half-clothed. A distraught look touched his face; he sprang from his bed and retreated. It frightened Isande, that this man she had feared so many years looked so vulnerable. She shuddered as Tejef took her hand in his, grinning at his half-brother the while.

“ Au, nasith sra-Mejakh,” said Tejef, “the m’metane-takdid inquire after you. I remember your feeling for her: Chimele forbade you, but any other nashas come near her at his peril, so she has been left quite alone in the matter of katasukke.I commend your taste, nasith.She is of great chanokhia.”

Knowing Khasif’s temper, Isande trembled; but the tall iduve simply bowed his head and turned away, sinking down on the edge of his cot. Pity touched her for Khasif: she would never have expected it in herself—but this man was hurt for her sake.

The room shrank again to the dimensions of Isande’s own quarters, and she wrenched herself from Tejef a loose grip with a cry of rage. Aiela fought to tell her something: she would not hear. She only saw Tejef laughing at her, and in that moment she was willing to kill or to die. She seized the metal table by its legs and swung at him, spilling its contents.

The metal numbed her hands with the force of the blow she had struck, and Tejef staggered back in surprise and flung up an arm to shield his face. She swung it again with a force reckless of strained arms and metal-scored hands, but this time he ripped the wreckage aside and sprang at her.

The impact literally jolted her senseless, and when she could see and breathe again she was on the floor under Tejef’s crushing weight. He gathered himself back, jerked her up with him. She screamed, and he bent both her arms behind her and drew her against him with such force that she felt her spine would be crushed. Her feet were almost off the floor and she dared not struggle. His heart pounded, the hard muscles of his belly jerked in his breathing, his lips snarled to show his teeth, a weapon the iduve did not scorn to use in quarrels among themselves. His eyes dilated all the way to black, and they had a dangerous madness in them now. She cried out, recognizing it.

The rubble gave, repaying recklessness, and Aiela went down the full length of the slide, stripping skin from his hands as he tried to stop himself, going down in a clatter of brick that could have roused the whole street had it been occupied. He hit bottom in choking dust, coughed and stumbled to his feet again, able to take himself only as far as the shattered steps before his knees gave under him. In his other consciousness he lurched along a hallway—Isande’s contact so heavily screened by shame he could not read it: guards at the door—Daniel crashed into them with a savagery unsuspected in the human, battered them left and right and hit the door switch, unlocking it, struggling to guard it for that vital instant as the recovering guards sought to tear him away.

“Khasif!” Daniel pleaded.

One of the guards tore his hand down and hit the close-switch, and Daniel interposed his own body in the doorway. Aiela flinched and screamed, anticipating the crushing of bones and the severing of flesh—but the door jammed, reversed under Khasif’s mind-touch. The big iduve exploded through the door and the human guards scrambled up to stop him—madness. One of them hit the wall, the echo booming up and down the corridor, the other went down under a single blow, bones broken; and Daniel flung himself out of Khasif’s way, shouting at him Isande’s danger, the third door down.

Khasif reached it, Daniel running after, Aiela urging him to get Isande out of the way—clenching his sweating hands, trying to penetrate Isande’s screening to warn her.

She gave way: Tejef’s face blurred in double vision over Daniel’s sight of the door. Khasif’s ominous tall form outlined in insane face and back overlay, receding and advancing at once. Isande cried out in pain as Khasif tore her from Tejef and hurled her out the door into Daniel’s arms: Daniel’s face superimposed over Khasif’s back, and then nothing, for Isande buried her face against the being that had lately been so loathsome to her, and clung to him; and Daniel, shaken, held to her with the same drowning desperation.

Metal crashed, and little by little Khasif was giving ground, until he was battling only to hold Tejef within the room.

Ship’s controls!Aiela screamed at his asuthi.

They tried. Section doors prevented them, and amaut guards and humans converged from all sides, forcing them into retreat. Khasif stood as helpless as they under the threat of a dozen weapons.

Tejef occupied the hallway, a dark smear of blood on his temple. He gave curt orders to the armed humans to hold the nasithfor him at the end of the hall. Aiela shuddered as he found that look resting next on Isande and on Daniel.

“Go to your quarters,” Tejef said very quietly. But when Daniel started to obey, too, Tejef tilted his head back and looked at him from eyes that had gone to mere slits. “No,” he said, “not you.”

Aiela,Isande appealed, Aiela, help him, oh help him!For she knew what Daniel had done for her.

Do as Tejef tells you,said Aiela. Daniel—give in, whatever happens: no temper. No resistance. They react to resistance. They lose interest otherwise.

“Sir,” said Daniel in a voice that needed no dissembling to carry a tremor, “sir—I acted not against you. For Isande, for her. Please.”

The iduve stared at him for a long cold moment. Then he let go a hissing breath. “Get out of my sight. Go to your quarters, and stay there or I will kill you.”

Go!Aiela hurled at Daniel: Bow your head and don’t look him in the eyes! Go!And blessedly the human ignored his own instincts, took the advice, and edged away carefully. He’s all right, he’s all right,Aiela said then to Isande, who collapsed in the wreckage of her quarters, crying. He probed gently to know if she were much hurt.

No,she flung back. No.Fear leaked through, shame, the ultimate certainty of defeat. Go away, go away,she kept thinking, o go away, reach the ship and leave. I learned to survive after losing Reha. It’s your turn. We’ve lost whatever chance we had because of me, because I started it, I did, I did, nothing gained.

It’s all right,came Daniel’s unbidden intervention. He shook all over, he was so afraid, alone in his quarters. It was a terrible thing for a man of his kind to yield down screens at such a moment: but along with the fear another process was taking place: he was gathering his mental forces to replot another attack. Of a sudden this humanish stubbornness, so different from kalliran methodical process, came to Isande as a thing of elethia.She wept, knowing his blind determination; and she appealed to Aiela to reason with him.

Luck,said Aiela, is what humans wish each other when they are in that frame of mind. I do not believe in luck:kastien forbids. But trust him, Isande. You’re going to be all right.

And that was a hope as irrational as Daniel’s, and as little honest. He did not want to tear his mind away, but the triple flood of thoughts distorted his perceptions and tore at his emotions. At last he had to let them both go, for he, like Daniel, was determined to try; and he knew what they would both say to that.

He had come at last near the streets of the occupied quarter. The sounds and smells of a habishtold him so, and guided him down the alley. It lacked some few hours until daylight, but by now even most of the night-loving amaut had given up and gone home. The place was quiet.

Thus, at the most one other street lay between him and the safety of headquarters, but far more effort would be needed to thread the maze of Weissmouth’s alleys, with their turnings often running into the impassable rubble of a ruined building. Aiela had no stomach for recklessness at this stage; but neither had he much more strength to spend on needless effort. He tried the handle of the habish’salley door, jerked it open, and walked through, to the startled outcries of the few drunken patrons remaining.

He closed the front door after him and found to his dismay that it was not the headquarters street after all: but at least it was clear and in the right section of town. He knew his way from here. The headquarters lay uphill and he set out in that direction, walking rapidly, hating the spots of light thrown by the occasional streetlamps.

A dark cross-street presented itself. He took it, hurrying yet faster. Footsteps sounded behind him, silent men, running. He gasped for air and gathered himself to run too, racing for what he hoped was the security of the main thoroughfare.

He rounded the corner and had sight of the bulk of the headquarters budding to his left, but those behind him were closing. He jerked out his gun as he ran, almost dropping it, whirled to fire.

A hurtling body threw him skidding to the pavement. Human bodies wrestled with him, beat the gun from his hand and pounded his head against the pavement until he was half-conscious. Then the several of them hauled him up and forced him to the side of the street where the shadows were thick.

He went where they made him go, not attempting further resistance until his head should clear. They held him by both arms and for half a block he walked unsteadily, loose-jointed. They were going toward the headquarters.

Then they headed him for a dark stairs into the basement door of some shop.

He had hoped in spite of everything that they were mercenaries in the employ of the amaut authorities that had muddled their instructions or simply seized the opportunity to vent their hate on an alien of any species at all. He could not blame them for that. But this put a grimmer face on matters.

He lunged forward, spilling them all, fought his way out of the tangle at the bottom of the steps, kneed in the belly the man quickest to try to hold him. Other hands caught at him: he hit another man in the throat and scrambled up the stairs running for his life, expecting a shot between the shoulders at any moment.

The headquarters steps were ahead. For that awful moment he was under the floodlights that illumined the front of the building, and rattling and pounding at the glass doors.

An amaut sentry waddled into the foyer and blinked at him, then hastened to open. Aiela pushed his way past, cleared the exposed position of the doors, leaned against the wall to catch his breath, staggered left again toward bnesychGerlach’s darkened office door, blazoned with the symbols of karshGomek authority.

“Most honorable sir,” the sentry protested, scurrying along at his side, “the bnesychwill be called.” He searched among his keys for that of the office and opened it. “Please sit down, sir. I will make the call myself.”

Aiela sank down gratefully upon the soft-cushioned low bench in the outer office while the sentry used the secretary’s phone to call the bnesych.He shook in reaction, and shivered in the lack of heating.

“Sir,” said the sentry, “the bnesychhas expressed his profound joy at your safe return. He is on his way. He begs your patience.”

Aiela thrust himself to his feet and leaned upon the desk, took the receiver and pushed the call button. The operator’s amaut-language response rasped in his ear.

“Get me contact with the iduve ship in the port,” he ordered in that language, and when the operator protested in alarm: “I am nas kame and I am asking you to contact my ship or answer to them.”

Again the operator protested a lack of clearance, and Aiela swore in frustration, paused open-mouthed as an amaut appeared in the doorway and bowed three times in respect. It was Toshi.

“Lord Aiela,” said the young woman, bowing again. “Thank you, Aphash. Resume your post. May I offer you help, most honorable lord nas kame?”

“Put me in contact with my ship. The operator refuses to recognize me.”

Toshi bowed, her long hands folded at her breast. “Our profound apologies. But this is not a secure contact. Please come with me to my own duty station next door and I will be honored to authorize the port operator to make that contact for you with no delay. Also I will provide you an excellent flask of marithe.You seem in need of it.”

Her procedures seemed improbable and he stood still, not liking any of it; but Toshi kept her hands placidly folded and her gray-green eyes utterly innocent. Of a sudden he welcomed the excuse to get past her and into the lighted lobby; but if he should move violently she would likely prove only a very startled young woman. He took a firmer grip on his nerves.

“I should be honored,” he said, and she bowed herself aside to let him precede her. She indicated the left-hand corridor as he paused in the lobby, and he could see that the second office was open with the light on. It seemed then credible, and he yielded to the offering motion of her hand and walked on with her, she waddling half a pace behind.

It was a communications station. He breathed a sigh of relief and returned the bow of the technician who arose from his post to greet them.

And a hard object in Toshi’s hand bore into his side. He did not need her whispered threat to stand still. The technician unhurriedly produced a length of wire from his coveralls and waddled around behind him, drawing his wrists back.

Aiela made no resistance, enduring in bitter silence, for if Toshi were willing to use that gun, he would be forever useless to his asuthi. He was surely going to join Isande and Daniel, and all that he could do now was take care that he arrived in condition to be of use to them. It was by no means necessary to Tejef that he survive.

They faced him about and took him out the door, down a stairs and to a side exit. Toshi produced a key and unlocked it, locked it again behind them when they stood on the steps of some dark side of the building.

Fire erupted out of the dark. The technician fell, bubbling in agony. Toshi crumpled with a whimper and scuttled off the steps against the building, while Aiela flung himself off, fell, struggled to his feet and sprinted in blind desperation for the lights of the main street.

Faster steps sounded behind him and a blow in the back threw him down, helpless to save himself. His shoulder hit the pavement as he twisted to shield his head, and humans surrounded him, hauled him up, and dragged him away with them. Aiela knew one of them by his cropped hair: they were the same men.

They took him far down the side street away from the lights and pulled him into an alley. Here Aiela balked, but a knee doubled him over, repaying a debt, and they forced him down into the basement of a darkened building. When they came to the bottom of the steps, he began to struggle, using knee and shoulders where he could; and all it won him was to be beaten down and kicked.

A dim light swung in the damp-breathing dark, a globe-lamp at the wrist of an amaut, casting hideous leaping shadows about them. Aiela heaved to gain his feet and scrambled for the stairs, but they kicked him down again. He saw the amaut thrust papers into the hands of one of the humans, snatching the stolen kalliran pistol from the man’s belt before he expected it and putting it into his own capacious pocket.

“Ffife ppasss,” the amaut said in human speech. “All ffree, all run country, go goodbpye.”

“How do we know what they say what you promised?” one made bold to ask.

“Go goodbpye,” the amaut repeated. “Go upplandss, ffree, no more amautss, goodbpye.”