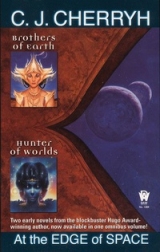

Текст книги "At the Edge of Space (Brothers of Worlds; Hunter of Worlds)"

Автор книги: C. J. Cherryh

Жанр:

Космическая фантастика

сообщить о нарушении

Текущая страница: 18 (всего у книги 36 страниц)

“Gods, are you leaving this moment? What am I to tell her?”

“I have said to her what I need to say.” Bel delayed a moment more, his hand upon the door, and looked back. “She was your best argument; I remain grateful you did not stoop to that. I will omit to wish you success, Kta. Do not be surprised if some of my people choose to die rather than agree with you. I will not even pray for t’Tefur’s death, when it may be the last the world will see of the nation we were. The name, my Indras friends, was Chtelek, not Sufak. But that probably will not matter hereafter.”

“Bel,” said Kta, “at least arm yourself.”

“Against whom? Yours—or mine? Thank you, no, Kta. I will see you at the harbor—or be in it tomorrow morning, whichever fortune brings me.”

The heavy door closed behind him, echoing through the empty halls, and Kta looked at Ian with a troubled expression.

“Do you trust him that far?” Ian t’Ilev asked.

“Begin no action against the Sufaki beyond Imas. I insist on that, Ian.”

“Is everything still according to original plan?”

“I will be there at nightfall. But one thing you can do: take Aimu with you and put her safely in a defended house. Elas will be no protection to her tonight.”

“She will be safe in Ilev. There will be men left to guard it, as many as we can spare: Uset’s women will be there too.”

“That will ease my mind greatly,” said Kta.

Aimu wept at the parting, as she had already been crying and trying not to. Before she did leave the house, she went to the phusmehaand cast into the holy fire her silken scarf. It exploded into brief flame, and she held out her hands in prayer. Then she came and put herself in the charge of Ian t’Ilev.

Kurt felt deeply sorry for her and found it hard to think Kta would not make some special farewell, but he bowed to her and she to him with the same formality that had always been between them.

“Heaven guard you, my brother,” she said softly.

“The Guardians of Elas watch over thee, my little sister, once of this house.”

It was all. Ian opened the door for her and shepherded her out into the street, casting an anxious eye across and up where the guards still stood on the rooftops, a reassuring presence. Kta closed the door again.

“How much longer?” Kurt asked. “It’s near dark. Shan t’Tefur undoubtedly has ideas of his own.”

“We are about to leave.”—T’Nethim appeared silently among the shadows of the further hall. Kta gave a jerk of his head and t’Nethim came forward to join them. “Stay by the threshold,” he ordered t’Nethim. “And be still. What I have yet to do does not involve you. I forbid you to invoke your Guardians in this house.”

T’Nethim looked uneasy, but bowed and assumed his accustomed place by the door, laying his sword on the floor before him.

Kta with Kurt walked into the firelit rhmei,and Kurt realized then the nature of Kta’s warning to t’Nethim, for he walked to the left wall of the rhmei,where hung the Sword of Elas, Isthain. The ypan-sulhad hung undisturbed for nine generations, untouched since the expulsion of the humans from Nephane, but for the sometime attention that kept its metal bright and its leather-wrapped hilt in good repair. The ypai-sulim,the Great Weapons, were unique to their houses and full of the history of them. Isthain, forged in Indresul when Nephane was still a colony, nearly a thousand years before, had been dedicated in the blood of a Sufaki captive in the barbaric past, carved into battle by eleven men before.

Kta’s hand hesitated at taking the age-dark hilt of it, but then he lifted it down, sheath and all, and went to the hearthfire. There he knelt and laid the great Sword on the floor, hands outstretched over it.

“Guardians of Elas,” he said, “waken, waken and hear me, all ye spirits who have ever known me or wielded this blade. I, Kta t’Elas u Nym, last of this house, invoke ye; know my presence and that of Kurt Liam t’Morgan u Patrick Edward, friend to this house. Know that at our threshold sits Lhe t’Nethim u Kma. Let your powers shield my friend and myself, and do no harm to him at our door. We take Isthain against Shan t’Tefur u Tlekef, and the cause of it you well know.—And you, Isthain, you shall have t’Tefur’s blood or mine. Against t’Tefur direct your anger and against no others. Long have you slept undisturbed, my dread sister, and I know the tribute due you when you are wakened. It will be paid by morning’s light, and after that time you will sleep again. Judge me, ye Guardians, and if my cause is just, give me strength. Bring peace again to Elas, by t’Tefur’s death or mine.”

So saying he took up the sheathed blade and drew it, the holy light running up and down the length of it as it came forth in his hand. Etched in its shining surface was the lightning emblem of the house, seeming to flash to life in the darkness of the rhmei.In both hands he lifted the blade to the light and rose, lifted it heavenward and brought it down again, then recovered the sheath and made it fast in his belt.

“It is done,” he said to Kurt. “Have a care of me now, though your human soul has its doubts of such powers. Isthain last drank of human life, and she is an evil creature, hard to put to sleep once wakened. She is eldest of the Sulimin Nephane, and self-willed.”

Kurt nodded and answered nothing. Whatever the temper of the spirit that lived in the metal, he knew the one which lived in Kta t’Elas. Gentle Kta had prepared himself to kill and, in truth, he did not want to stand too near, or to find any friend in Kta’s path.

And when they came to the threshold where t’Nethim waited, Lhe t’Nethim bowed his face to the stone floor and let Kta pass the door before he would rise; but when Kurt delayed to close the door of Elas and secure it, t’Nethim gathered himself up and crept out into the gathering dark, the look on his perspiring face that of a man who had indeed been brushed by something that sought his life.

“He has prayed your safety,” Kurt ventured to tell him.

“Sometimes,” said Lhe t’Nethim, “that is not enough. Go ahead, t’Morgan, but be careful of him. It is the dead of Elas who live in that thing. Mim my cousin—”

He ceased with a shiver, and Kurt put the nemet superstition out of mind with a horror that Mim’s name could be entangled in the bloody history of Isthain.

He ran to overtake Kta, and knew that Lhe t’Nethim, at a safe distance, was still behind them.

23

“There” said Ian t’Ilev,nodding at the iron gate of the Afen. “They have several archers stationed inside. We are bound to take a few arrows. You and Kurt must have most care: they will be directly facing you for a few moments.”

Kta studied the situation from the vantage point in the door of Irain. It was dark, and there were only ill-defined shapes to be seen, the wall and the Afen a hulking mass. “We cannot help that. Let us go. Now.”

Ian t’Ilev bowed shortly, then broke from cover, darting across the street.

In an instant came a heart-stopping shriek, and from the main street poured a force of men bearing torches and weapons: the Indras-descended came in direct attack against the iron gate of the Afen, bearing a ram with them.

White light illuminated the court of the Afen, blinding, and there was an answering Sufak ululation from inside the wall. The blows of the ram began to resound against the iron bars.

Kurt and Kta held a moment, while men from Isulan poured around them. Then Kta broke forth and they followed him to the shadow of the wall. Scaling-poles went up.

The first man took with him the line that would aid their descent on the other side. He gained the top and rolled over, the line jerking taut in the hands of those who secured it on the hitherside.

The next man swarmed up to the top and then it was Kurt’s turn. Floodlights swung over to them now, spotting them, arrows beginning to fly in their direction. One hissed over Kurt’s head. He hooked a leg over the wall, flung himself over and slid for the bottom, stripping skin from his hands on the knotted line.

The man behind him made it, but the next came plummeting to earth, knocking the other man to the ground. There was no time to help either. Kta landed on his feet beside him, broke the securing thong and ripped Isthain from its sheath. Kurt drew his own ypanas they ran, trying to dodge clear of the tracking floodlight.

The wall of the Afen itself provided them shelter, and there they regrouped. Of the twenty-four who had begun, at least six were missing.

T’Nethim was the last into shelter. They were nineteen.

Kta gestured toward the door of the Afen itself, and they slipped along the wall toward it, the place where the Methi’s guard had taken their stand. Men, they knew those, but there was no mercy in the arrows which had already taken toll of them, and none in the plans they had laid. The door must be forced.

With a crash of iron the wall-gate gave way and the Indras under Ian t’Ilev surged forward in a frontal assault on the door to the Afen,—the Sufaki archers, standing and kneeling, firing as rapidly as they could; and Kta’s small force hit the bowmen from the flank, creating precious seconds of diversion. Isthain struck without mercy, and Kurt wielded his own blade with less skill but no less determination.

The swordless archers gave up the bows at such unexpected short range and resorted to long daggers, but they had no chance against the ypai,cut down and overrushed. The charge of the Indras carried to the very door, over the bodies of the Methi’s valiant guard, bringing the ram’s metal-spiked weight to bear with slow and shattering force against the bronze-plated wood.

From inside, over all the booming and shouting, came a brief piercing whine. Kurt knew it, froze inside, caught Kta by the shoulder and pulled him back, shouting for the others to drop, but few heard him.

The Afen door dissolved in a sheet of flame and the ram and the men who wielded it were slag and ashes in the same instant. The Indras still standing were paralyzed with shock or they might have fled; and there came the click and whine as the alien field-piece in the inner hall built up power for the next burst of fire.

Kurt flung himself through the smoking doorway, to the wall inside and out of the line of fire. The gunners swung the barrel about on its tripod to aim at him against the wall, and he dropped, sliding as it moved, the beam passing over his head with a crackle of energy and a breath of heat.

The wall shattered, the support beams turning to ash in that instant; and Kurt scrambled up now with a shout as wild as that of the Indras, several seconds his before the weapon could fire again.

He took the gunner with a sweep of his blade, his ears hurting as the unmanned gun gathered force again, a wild scream of energy. A second man tried to turn it on the Indras who were pouring through the door.

Kurt ran him through, ignoring the man who was thrusting a pike at his own side. The hot edge of metal raked his back and he fell, rolled for protection. The Sufaki above him was aiming the next thrust for his heart. Desperately he parried with his blade crosswise and deflected the point up—the iron head raked his shoulder and grated on the stone floor.

In the next instant the Sufaki went down with Isthain through his ribs, and Kta paused amid the rush to give Kurt his hand and help him up.

“Get back to safety,” Kta advised him.

“I am all right,– No!” he cried as he saw the Indras preparing to topple the live gun to the flooring. He staggered to the weapon that still hummed with readiness and swung it to where the Indras were pressing forward against the next barred doorway, trying vainly to batter it with shoulders and blades. Behind him the shattered wall and dust and chips of stone sifting down from the ceiling warned how close the area was to collapse. There was need of caution. He controlled the mishandled weapon to a tighter, less powerful beam.

“Have a care,” Kta said. “I do not trust that thing.”

“Clear your men back,” said Kurt, and Kta shouted at them. When they realized what he was about, they scrambled to obey.

The doorway dissolved, the edges of the blasted wood charred and blackened, and Kurt powered down while the Indras surged forward again and opened the ruined doors.

The inner Afen stood open to them now, the lower halls vacant of defenders. For a moment there was silence. There were the stairs leading up to the Methi’s apartments, to the human section, which other weapons would guard.

“She has given her weapons to the Sufaki,” Kurt said. “There is no knowing what the situation is up there. We have to take the upper level. Help me. We need this weapon.”

“Here,” said Ben t’Irain, a heavyset man who was housefriend to Elas. He took the thing on his broad shoulder and gestured for one of his cousins to take its base as Kurt kicked the tripod and collapsed it.

“If we meet trouble,” Kurt told him, “drop to your knee and hold this end straight toward the target. Leave the rest to me.”

“I understand,” said the man calmly, which was bravery for a nemet, much as they hated machines. Kurt gave the man a nod of respect and motioned the men to try the stairway.

They went quickly and carefully now, ready for ambush at any turn. Kurt privately feared a mine, but that was something he did not tell them: they had no other way.

The door at the top of the stairs was closed, as Kurt had known it must be; and with Ben to steady the gun, he blasted the wood to cinders, etching the outline of the stone arch on the wall across the hall. The weapon started to gather power again, beginning that sinister whine, and Kurt let it, dangerous as it was to move it when charged: it had to be ready.

They entered the hall leading to the human section of the Afen. There remained only the door of Djan’s apartments.

Kurt held up a hand signaling caution, for there must be opposition here as nowhere else.

He waited. Kta caught his eye and looked impatient, out of breath as he was.

With Djan to reckon with, underestimation could be fatal to all of them. “Ben,” he said, “this may be worth your life and mine.”

“What will you?” Ben t’Irain asked him calmly enough, though he was panting from the exertion of the climb. Kurt nodded toward the door.

T’Irain went with him and took up position, kneeling. Kurt threw the beam dead center, fired.

The door ceased to exist, and in the reeking opening was framed a heap of twisted metal, the shapes of two men in pale silhouette against the cindered wall beyond, where their bodies and the gun they had manned had absorbed the energy.

A movement to the right drew Kurt’s attention. There was a burst of light as he turned and Ben t’Irain gasped in pain and collapsed beneath the gun.

T’Tefur. The Sufaki swung the pistol left at Kurt and Kurt dropped, the beam raking the wall where he had been. In that instant two of the Indras rushed the Sufaki leader, one shot down, and Kta, the other one, grazed by the bolt.

Kta vaulted the table between them and Isthain swept in an invisible downstroke that cleaved the Sufaki’s skull. The pistol discharged undirected and Kta staggered, raked across the leg as t’Tefur’s dying hands caught at him and missed. Then Kta pulled himself erect and leaned on Isthain as he turned and looked back at the others.

Kurt edged over to the whining gun and shut it down, then touched t’Irain’s neck to find that there was no heartbeat. T’Tefur’s first shot had been true.

He gathered his shaking limbs under him and rose, leaning on the charred doorframe; the heat made him jerk back, and he staggered over to join Kta, past Ian t’Ilev’s sprawled body, for he was the other man t’Tefur had shot down before dying.

Kta had not moved. He still stood by t’Tefur, both his hands on Isthain’s pommel. Then Kurt bent down and took the gun from Shan t’Tefur’s dead fingers, with no sense of triumph in the action, no satisfaction in the name of Mim or the other dead the man had sent before him.

It was a way of life they had killed, the last of a great house. He had died well. The Indras themselves were silent, Kta most of all.

A small silken form burst from cover behind the couch and fled for the open door. T’Ranek stopped her, swept her struggling off her feet and set her down again.

“It is the chanof the Methi,” said Kta, for it was indeed the girl Pai t’Erefe, Sufaki, Djan’s companion. Released, she fell sobbing to her knees, a small, and shaken figure in that gathering of warlike men: but she was also of the Afen, so when she had made the necessary obeisance to her conquerors, she sat back with her little back stiff and her head erect.

“Where is the Methi?” Kta asked her, and Pai set her lips and would not answer. One of the men reached down and gripped her arm cruelly.

“No,” Kurt asked of him, and dropped to one knee, fronting Pai. “Pai, Pai, speak quickly. There is a chance she may live if you tell me.”

Pai’s large eyes reckoned him, inside and out. “Do not harm her,” she pleaded.

“Where is she?”

“The temple—” When he rose she sprang to her feet, holding him, compelling his attention. “My lord, t’Tefur wanted her greater weapons. She would not give them. She refused him. My lord Kurt, my lord, do not kill her.”

“The chanis probably lying,” said t’Ranek, “to gain time for the Methi to prepare worse than this welcome.”

“I am not lying,” Pai sobbed, gripping Kurt’s arm shamelessly rather than be ignored. “Lord Kurt, you know her. I am not lying.”

“Come on.” Kurt took her by the arm and looked at the rest of them, at Kta most particularly, whose face was pale and drawn with the shock of his wound. “Hold here,” he told Kta. “I am going to the temple.”

“It is suicide,” said Kta. “Kurt, you cannot enter there. Even we dare not come after her there, no Indras—”

“Pai is Sufaki and I am human,” said Kurt, “and no worse pollution there than Djan herself. Hold the Afen. You have won, if only you do not throw it away now.”

“Then take men with you,” Kta pleaded with him, and when he ignored the plea: “Kurt, Elas wants you back.”

“I will remember it.”

He hurried Pai with him, past t’Irain’s corpse at the door and down the hall to the inner stairs. He kept one hand on her arm and held the pistol in the other, forcing the chanalong at a breathless pace.

Pai sobbed, pattering along with small resisting steps, tripping in her skirts on the stairs, though she tried to hold them with her free hand. He shook her as they came to the landing, not caring that he hurt.

“If they reach her first,” he said, “they will kill her, Pai. As you love her, move.”

And after that, Pai’s slippered feet hurried with more sureness, and she had swallowed down her tears, for the brave little chanhad not needed to trip so often. She hurried now under her own power.

They came into the main hall, through the rest of the Indras, and men stared, but they did not challenge him; everyone knew Elas’ human. Pai stared about her with fear-mad eyes, but he hastened her through, beneath the threatening ceiling at the main gate and to the outside, past the carnage that littered the entrance. Pai gave a startled gasp and stopped. He drew her past quickly, not much blaming the girl.

The night wind touched them, cold and clean after the stench of burning flesh in the Afen. Across the floodlit courtyard rose the dark side of Haichema-tleke, and beneath it the wall and the small gate that led out into the temple courtyard.

They raced across the lighted area, fearful of some last archer, and reached the gate out of breath.

“You,” Kurt told Pai, “had better be telling the truth.”

“I am,” said Pai, and her large eyes widened, fixed over his shoulder. “Lord! Someone comes!”

“Come,” he said, and, blasting the lock, shouldered the heavy gate open. “Hurry.”

The temple doors stood ajar, far up the steps past the three triangular pylons. The golden light of Nephane’s hearthfire threw light over all the square and hazed the sky above the roof-opening.

Kurt drew a deep breath and raced upward, dragging Pai with him, she stumbling now from exhaustion. He put his arm about her and half-carried her, for he would not leave her alone to face whatever pursued them. Behind them he could hear shouting rise anew from the main gate, renewed resistance—cheers for victory—he did not pause to know.

Within, the great hearthfire came in view, roaring up from its circular pit to the gelos,the aperture in the ceiling, the smoke boiling darkly up toward the black stones.

Kurt kept his grip on Pai and entered cautiously, keeping near the wall, edging his way around it, surveying all the shadowed recesses. The fire’s burning drowned his own footsteps and its glare hid whatever might lie directly across it. The first he might know of Djan’s presence could be a darting bolt of fire deadlier than the fire that burned for Phan.

“Human.”

Pai shrieked even as he whirled, throwing her aside, and he held his finger still on the trigger. The aged priest, the one who had so nearly consigned him to die, stood in a side hall, staff in hand, and behind him appeared other priests.

Kurt backed away uneasily, darted a nervous glance further left, right again toward the fire.

“Kurt,” said Djan’s voice from the shadows at his far right.

He turned slowly, knowing she would be armed.

She waited, her coppery hair bright in the shadows, bright as the bronze of the helmeted men who waited behind her; and the weapon he had expected was in her hand. She wore her own uniform now, that he had never seen her wear, green that shimmered with synthetic unreality in this time and place.

“I knew,” she said, “when you ran, that you would be back.”

He cast the gun to the ground, demonstrating both hands empty. “I’ll get you out. It’s too late to save anything, Djan. Give up. Come with me.”

“What, have you forgiven, and has Elas? They sent you here because they won’t come here. They fear this place. And Pai, for shame, Pai,—”

“Methi,” wailed Pai, who had fallen on her face in misery, “Methi, I am sorry.”

“I do not blame you. I have expected him for days.” She spoke now in Nechai. “And Shan t’Tefur?”

“He is dead,” said Kurt.

There was no grief, only a slight flicker of the eyes. “I could no longer reason with him. He saw things that could not exist, that never had existed. So others found their own solutions, they tell me. They say the Families have gone over to Ylith of Indresul.”

“To save their city.”

“And will it?”

“I think it has a chance at least.”

“I thought,” she said, “of making them listen. I had the firepower to do it—to show them where we came from.”

“I am thankful,” he said, “that you didn’t.”

“You made this attack calculating that I wouldn’t.”

“You know the object lesson would be pointless. And you have too keen a sense of responsibility to get these men killed defending you. I’ll help you get out, into the hills. There are people in the villages who would help you. You can make your peace with Ylith-methi later.”

She smiled sadly. “With a world between us, how did we manage to do it? Ylith will not let it rest. And neither will Kta t’Elas.”

“Let me help you.”

Djan moved the gun she had held steadily on him, killed the power with a pressure of her thumb. “Go,” she told her two companions. “Take Pai to safety.”

“Methi,” one protested. It was t’Senife. “We will not leave you with him.”

“Go,” she said, but when they would not, she simply held out her hand to Kurt and started with him to the door, the white-robed priests melting back before them to clear the way.

Then a shadow rose up before them.

T’Nethim.

A blade flashed. Kurt froze, foreseeing the move of Djan’s hand, whipping up the pistol. “Don’t!” he cried out to them both.

The ypanarced down.

A cry of outrage roared in his ears. He seized t’Nethim’s arm, thrown sprawling as the Sufaki guards went for the man. Blades lifted, fell almost simultaneously. T’Nethim sprawled down the steps, over the edge, leaving a dark trail behind him.

Kurt struggled to his knees, saw the awful ruin of Djan’s shoulder and knew, though she still breathed, that she was finished. His stomach knotted in panic. He thought that her eyes pitied him.

Then they lost the look of life, the firelight from the doorway flickering across their surface. When he gathered her up against him she was loose, lifeless.

“Let her go,” someone ordered.

He ignored the command, though it was in his mind that in the next moment a Sufak dagger could be through his back. He cradled Djan against him, aware of Pai sobbing nearby. He did not shed tears. They were stopped up in him, one with the terror that rested in his belly. He wished they would end it.

A deafening vibration filled the air, moaning deeply with a sighing voice of bronze, the striking of the Inta,the notes shaking and chilling the night. It went on and on, time brought to a halt, and Kurt knelt and held her dead weight against his shoulder until at last one of the younger priests came and knelt, holding out his hands in entreaty.

“Human,” said the priest, “please, for decency’s sake,—let us take her from this holy place.”

“Does she pollute your shrine?” he asked, suddenly trembling with outrage. “She could have killed every living thing on the shores of the Ome Sin. She could not even kill one man.”

“Human,” said t’Senife, half kneeling beside him. “Human, let them have her. They will treat her honorably.”

He looked up into the narrow Sufaki eyes and saw grief there. The priests pulled Djan from him gently, and he made the effort to rise, his clothes soaked with her blood. He shook so that he almost fell, and turned dazed eyes upon the temple square, where a line of Indras guards had ranged themselves. Still the Intasounded, numbing the very air and in small groups men came moving slowly toward the shrine.

They were Sufaki.

He was suddenly aware that all around him were Sufaki, save for the distant line of Indras swordsmen who stood screening the approach to the temple.

He looked back, realizing they had taken Djan. She was gone, the last human face of his own universe that he would ever see. He heard Pai crying desolately, and almost absently bent and drew her to her feet, passing her into t’Senife’s care.

“Come with me,” he bade t’Senife. “Please. The Indras will not attack. I will get you both to safety. There should be no more killing in this place.”

T’Senife yielded, nodded to his companion, tired men, both of them, with tired, sorrowful faces.

They came down the long steps. Indras turned, ready to take the three Sufaki, the men and the chanPai, in charge, but Kurt put himself between.

“No,” he said. “There is no need. We have lost t’Nethim; they have lost a Methi. She is dead. Let them be.”

One was t’Nechis, who heard that news soberly and bowed and prevented his men. “If you look for Kta t’Elas,” said t’Nechis, “seek him toward the wall.”

“Go your way,” Kurt bade the Sufaki, “or stay with me if you will.”

“I will stay with you,” said t’Senife, “until I know what the Indras plan to do with Nephane.” There was cynicism in his voice, but it surely masked a certain fear, and the Methi’s guards walked with him as he walked behind the Indras line in search of Kta.

He found Kta among the men of Isulan, with his leg bandaged and with Isthain now secure at his belt. Kta looked up in shock—joy damped by fear. Kurt looked down at his bloody hand and found it trembling and his knees likely to give out.

“Djan is dead,” said Kurt.

“Are you all right?” Kta asked.

Kurt nodded, and jerked his head toward the Sufaki. “They were her guards. They deserve honor of that.”

Kta considered them, inclined his head in respect. “T’Senife,—help us. Stand by us for a time, so that your people may see that we mean them no harm. We want the fighting stopped.”

The rumor was spreading among the people that the Methi was dead. The Intahad not ceased to sound. The crowd in the square increased steadily.

“It is Bel t’Osanef,” said Toj t’Isulan.

It was in truth Bel, coming slowly through the crowd, pausing to speak a word, exchange a glance with one he knew. Among some his presence evoked hard looks and muttering, but he was not alone. Men came with him, men whose years made the crowd part for them, murmuring in wonder: the elders of the Sufaki.

Kta raised a hand to draw his attention, Kurt beside him, though it occurred to him what vulnerable targets they both were.

“Kta,” Bel said, “Kta, is it true,—the Methi is dead?”

“Yes,” said Kta, and to the elders, who expressed their grief in soft murmurings: “That was not planned. I beg you, come into the Afen. I will swear on my life you will be safe.”

“I have already sworn on mine,” said Bel. “They will hear you. We Sufaki are accustomed to listen, and you Indras to making laws. This time the decision will favor us both, my friend, or we will not listen.”

“We could please some in Indresul,” said Kta, “by disavowing you. But we will not do that. We will meet Ylith-methi as one city.”

“If we can unite to surrender,” said one elder, “we can to fight.”

Then it came to Kurt, like an incredibly bad dream: the human weapons in the citadel.

He fled, startling Kta, startling the Indras, so that the guard at the gate nearly ran him through before he recognized him in the dark.

But Elas’ human had leave to go where he would.

Heart near to bursting, Kurt raced through the battlefield of the court, up the stairs, into the heights of the Afen.

Even those on watch in the Methi’s hall did not challenge him until he ordered them sharply from the room and drew his ypanand threatened them. They yielded before his wild frenzy, hysterical as he was, and fled out.

“Call t’Elas,” a young son of Ilev urged the others. “He can deal with this madman.”

Kurt slammed the door and locked it, overturned the table and wrestled it into position against the door, working with both hands now, barring it with yet more furniture. They struck it from the outside, but it was secure. Then they went away.

He sank down, trembling, too weary to move. In time he heard the voice of Kta, of Bel, even Pai pleading with him.

“What are you doing?” Kta cried through the door. “My friend, what do you plan to do?”