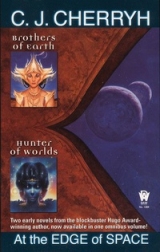

Текст книги "At the Edge of Space (Brothers of Worlds; Hunter of Worlds)"

Автор книги: C. J. Cherryh

Жанр:

Космическая фантастика

сообщить о нарушении

Текущая страница: 2 (всего у книги 36 страниц)

2

Alarge hall was on the third level. Its walls were of the same irregular stone as the outer hall, but the floor had carpets and the walls were hung with tapestries. The guards sent him beyond this point alone, toward the next door.

The room beyond the threshold was of his own world, metal and synthetics, white light. The furnishings were crystal and black, the walls were silver. Only the cabinet at his left and the door at his back did not belong: they were carved wood, convoluted dragon figures and fishes.

The door closed softly, sealing him in.

Machinery purred and he glanced leftward. A woman in nemet dress had joined him. Her gown was gold, high-collared, floor-length. Her hair was amber, curling gently. She was human.

Hanan.

She treated him with more respect than the nemet, keeping her distance. She would know his mind, as he knew hers; he made no move against her, would make none until he was sure of the odds.

“Good day, Mr. Morgan—Lieutenant Morgan.” She had a disk in her fingers, letting it slide on its chain. Suddenly he missed it. “Kurt Liam Morgan. Pylan, I read it.”

“Would you mind returning it?” It was his identity tag. He had worn it since the day of his birth, and it was unnerving to have it in her hands, as if a bit of his life dangled there. She considered a moment, then tossed it. He caught it.

“We have one name,” she said, which was common knowledge. “I’m Djan. My number—you would forget. Where are your crewmates, Kurt Morgan?”

“Dead. I’ve told the truth from the beginning. There were no other survivors.”

“Really.”

“I am alone,” he insisted, frightened, for he knew the lengths to which they could go trying to obtain information he did not have. “Our ship was destroyed in combat. The life-capsule from Communications was the only one that cleared on either side, yours or ours.”

“How did you come here?”

“Random search.”

Her lips quivered. Her eyes fixed on his with cold fury. “You did not happen here. Again.”

“We met one of your ships,” he said, and his mouth was suddenly dry; he began to surmise how she knew it was a lie, and that they would have all the truth before they were done. It was easier to yield it, hoping against expectation that these Aeolids would dispose of him without revenge.

“Aeolus was your world, wasn’t it?”

“Details,” she said. Her face was white, but the control of her voice was unfaltering. He had respect for her. The Hanan were cold, but it took more than coldness to receive such news with calm. He knew. Pylos also was a dead world. He remembered Aeolus hanging in space, the glare of fires spotting its angry surface. Even an enemy had to feel something for that, the death of a world.

“Two Alliance ISTs penetrated the Aeolid zone with thirty riders. We were with that force. One of your deepships jumped into the system after the attack, jumped out again immediately when they realized the situation there. We were nearest, saw them, locked to track—it brought us here. We—fought. You monitored that, didn’t you? You know there were no other survivors.”

“Keep going.”

“That’s all there is. We finished each other. We suffered the first hit and my station capsuled then. That’s all I know. I had no part in the combat. I looked for other capsules. There were none. You knowthere were no others.”

An object was concealed in her hand. He caught a glimpse of it as her hand moved by her many-folded skirts. He saw her fingers close, then relax. He almost took the chance against her then, but she was Hanan and trained from infancy: her reflexes would be instant, and there was the chance the weapon was set to stun. That possibility was more deterrent than any quick oblivion.

“I know,” she said, “that there are no other ships, that at least.” Her tone was low and mocking. “Welcome to my world, Kurt Morgan. We seem to be humanity’s orphans in this limb of nowhere,—there being only the Tamurlin for company otherwise, and they’re not really human any longer.”

“You’re alone?”

“Mr. Morgan. If something happens to me at your hands, I’ve given the nemet orders to turn you out naked as the day you were born on the shore of the Tamur. The other humans in this world will know how to deal with you in a way humans understand.”

“I don’t threaten you.” Hope turned him shameless. “Give me the chance to leave. You’ll never see me again.”

“Unless you’re the forerunner of others.”

“There are no others,” he insisted.

“What security do you give me for that promise?”

“We were alone. We came alone. There was no way we could have been traced. There were no ships near enough and we jumped blind, without coordinates.”

“Well,” she said, and even appeared to accept what he said, “well, it will be a long wait then. Aeolus colonized this world three hundred years ago. But the war—the war—Records were scrambled, the supply ship was lost somehow. We discovered this world in archives centuries old on Aeolus and came to reclaim it. But you seem to have intervened in a very permanent way on Aeolus. Our ship is gone: it could only have been the one you claim to have destroyed; your ship is gone—you claim you could not be traced; Aeolus and its records are cinders. Exploration in this limb ceased, a hundred years ago. What do you suppose the odds are on someone chancing across us?”

“There there is no war. Let me leave.”

“If I did,” she said, “you might die out there: the world has its dangers. Or you might come back. You might come back, and I could never be sure when you would do that. I would have to fear you for the rest of my life. I would have no more peace here.”

“I would not come back.”

“Yes, you would. You would. It’s been six months—since my crew died here. After only that long, my own face begins to look strange to me in a mirror; I begin to fear mirrors. But I look. I could want another human face to look at,—after a certain number of years. So would you.”

She had not raised the weapon he was now sure she had. She did not want to use it. Hope turned his hands damp, sent the sweat running down his sides. She knew the only safe course for her. She was mad if she did not take it. Yet she hesitated, her face greatly distressed.

“Kta t’Elas came,” she said, “and begged for your freedom. I told him you were not to be trusted.”

“I swear to you, I have no ambitions,—only to stay alive, I would go to him—I would accept any conditions, any terms you set.”

She moved her hands together, clasping the weapon casually in her slim fingers. “Suppose I listened to you.”

“There would be no trouble.”

“I hope you remember that, when you grow more comfortable. Remember that you came here with nothing, with nothing—not even the clothes on your back; and that you begged anyterms I would give you.” She gazed at him soberly for a moment, unmoving. “I am out of my mind. But I reserve the right to collect on this debt someday, in whatever manner and for however long I decide. You are here on tolerance. And I will try you. I am sending you to Kta t’Elas, putting you in his charge for two weeks. Then I will call you back, and we will review the situation.”

He understood it for a dismissal, weak-kneed with relief and now beset with new doubts. Alone, presented with an enemy, she did a thing entirely unreasonable: it was not the way he had known the Hanan, and he began to fear some subtlety, a snare laid for someone.

Or perhaps loneliness had its power even on the Hanan, destructive even of the desire to survive. And that thought was no less disquieting in itself.

3

To judge by the size of the house and its nearness to the Afen, Kta was an important man. From the street the house of Elas was a featureless cube of stone with its deeply recessed A-shaped doorway fronting directly on the walk. It was two stories high, and sprawled far back against the rock on which Nephane sat.

The guards who escorted him rang a bell that hung before the door, and in a few moments the door was opened by a white-haired and balding nemet in black.

There was a rapid exchange of words, in which Kurt caught frequently the names of Kta and Djan-methi. It ended with the old man bowing, hands to lips, and accepting Kurt within the house, and the guards bowing themselves off the step. The old man softly closed the double doors and dropped the bar.

“Hef,” the old man identified himself with a gesture. “Come.”

Hanging lamps of bronze lit their way into the depths of the house, down a dim hall that branched Y-formed past a triangular arch. Stairs at left and right led to a balcony and other rooms, but they took the right-hand branch of the Y upon the main floor. On the left the wall gave way into that same central hall which appeared through the arch at the joining of the Y. On the right was a closed door. Hef struck it with his fingers.

Kta answered the knock, his dark eyes astonished. He gave full attention to Hef’s rapid words, which sobered him greatly; then he opened the door widely and bade Kurt come in.

Kurt entered uncertainly, disoriented equally by exhaustion and by the alien geometry of the place. This time Kta offered him the honor of a chair, still lower than Kurt found natural. The carpets underfoot were rich with designs of geometric form and the furniture was fantastically carved, even the bed surrounded with embroidered hangings.

Kta settled opposite him and leaned back. He wore only a kilt and sandals in the privacy of his own chambers. He was a powerfully built man, golden skin glistening like the statue of some ancient god brought to life; and there was about him the power of wealth that had not been apparent on the ship. Kurt suddenly found himself awed of the man, and suddenly realized that “friend” was perhaps not the proper word between a wealthy nemet captain and a human refugee who had landed destitute on his doorstep.

Perhaps, he thought uneasily, “guest” was hardly the proper word either.

“Kurt-ifhan,” said Kta, “the Methi has put you in my hands.”

“I am grateful,” he answered, “that you came and spoke for me.”

“It was necessary. For honor’s sake, Elas has been opened to you. Understand: if you do wrong, punishment falls on me. If you escape, my freedom is owed. I say this so you will know. Do as you choose.”

“You took a responsibility like that,” Kurt objected, “without knowing anything about me.”

“I made an oath,” said Kta. “I didn’t know then that the oath is an error. I made an oath of safety for you. For the honor of Elas I have asked the Methi for you. It is necessary.”

“Her people and mine have been at war for more than two thousand years. You’re taking a bigger risk than you know. I don’t want to bring trouble on you.”

“I am your host fourteen days,” said Kta. “I thank you that you speak plainly; but a man who comes to the hearthfire of Elas is never a stranger at our door again. Bring peace with you and be welcome. Honor our customs and Elas will share with you.”

“I am your guest,” said Kurt. “I will do whatever you ask of me.”

Kta joined his fingertips together and inclined his head. Then he rose and struck a gong that hung beside his door, bringing forth a deep, soft note which caressed the mind like a whisper.

“I call my family to the rhmei—the heart—of Elas. Please.” He touched fingers to lips and bowed. “This is courtesy, bowing. Ei,I know humans touch to show friendliness. You must not. This is insult, especially to women. There is blood for insulting the women of a house. Lower your eyes before strangers. Extend no hand close to a man. This way you cannot give offense.”

Kurt nodded, but he grew afraid, afraid of the nemet themselves, of finding some dark side to their gentle, cultured nature—or of being despised for a savage. That would be worst of all.

He followed Kta into the great room which was framed by the branching of the entry hall. It was columned, of polished black marble. Its walls and floors reflected the fire that burned in a bronze tripod bowl at the apex of the triangular hall.

At the base wall were two wooden chairs, and there sat a woman in the left-hand one, her feet on a white fleece, as other fleeces scattered about her feet like clouds. In the right-hand chair sat an elder man, and a girl sat curled upon one of the fleece rugs. Hef stood by the fire, with a young woman at his side.

Kta knelt on the rug nearest the lady’s feet, and from that place spoke earnestly and rapidly, while Kurt stood uncomfortably by and knew that he was the subject. His heart beat faster as the man rose up and cast a forbidding look at him.

“Kurt-ifhan,” said Kta, springing anxiously to his feet, “I bring you before my honored father, Nym t’Elas u Lhai, and my mother the lady Ptas t’Lei e Met sh’Nym.”

Kurt bowed very low indeed, and Kta’s parents responded with some softening of their manner toward him. The young woman by Nym’s feet also rose up and bowed.

“My sister Aimu,” said Kta. “And you must also meet Hef and his daughter Mim, who honor Elas with their service. Ita, Hef-nechan s’Mim-lechan, imimen. Hau.”

The two came forward and bowed deeply. Kurt responded, not knowing if he should bow to servants, but he matched his obeisance to theirs.

“Hef,” said Kta, “is the Friend of Elas. His family serves us now three hundred years. Mim-lechan speaks human language. She will help you.”

Mim cast a look up at him. She was small, narrow-waisted, both stiffly proper and distractingly feminine in the close-fitting, many-buttoned bodice. Her eyes were large and dark, before a quick flash downward and the bowing of her head concealed them.

It was a look of hate, a thing of violence, that she sent him.

He stared, stricken by it, until he remembered and showed her courtesy by glancing down.

“I am much honored,” said Mim coldly, like a recital, “being help to the guest of my lord Kta. My honored father and I are anxious for your comfort.”

The guest quarters were upstairs, above what Mim explained shortly were Nym’s rooms,—with the implication that Nym expected silence of him. It was a splendid apartment, in every detail as fine as Kta’s own, with a separate, brightly tiled bath, a wood-stove for heating water, bronze vessels for the bath and a tea set. There was a round tub in the bath for bathing, and a great stack of white linens, scented with herbs.

The bed in the main triangular room was a great feather-stuffed affair spread with fine crisp sheets and the softest furs, beneath a sunny window of cloudy, bubbled glass. Kurt looked on the bed with longing, for his legs shook and his eyes burned with fatigue, and there was not a muscle in his body which did not ache; but Mim busily pattered back and forth with stacks of linens and clothing, and then cruelly insisted on stripping the bed and remaking it, turning and plumping the big brown mattress. Then, when he was sure she must have finished, she set about dusting everything.

Kurt was near to falling asleep in the corner chair when Kta arrived in the midst of the confusion. The nemet surveyed everything that had been done and then said something to Hef, who attended him.

The old servant looked distressed, then bowed and removed a small bronze lamp from a triangular niche in the west wall, handling it with the greatest care.

“It is religion,” Kta explained, though Kurt had not ventured to ask. “Please don’t touch such things—also the phusmeha,the bowl of the fire in the rhmei.Your presence is a disturbance. I ask your respect in this matter.”

“Is it because I am a stranger,” Kurt asked, already nettled by Mim’s petty persecutions, “or because I’m human?”

“You are without beginning on this earth. I asked the phusataken out not because I don’t wish Elas to protect you, but because I don’t want you to make trouble by offending against the Ancestors of Elas. I have asked my father in this matter. The eyes of Elas are closed in this one room. I think it is best. Let it not offend.”

Kurt bowed, satisfied by Kta’s evident distress.

“Do you honor your ancestors?” Kta asked.

“I don’t understand,” said Kurt, and Kta assumed a distressed look as if his fears had only been confirmed.

“Nevertheless,” said Kta, “I try. Perhaps the Ancestors of Elas will accept prayers in the name of your most distant house. Are your parents still living?”

“I have no kin at all,” said Kurt, and the nemet murmured a word that sounded regretful.

“Then,” said Kta, “I ask please your whole name, the name of your house and of your father and your mother.”

Kurt gave them, to have peace, and the nemet stumbled much over the long alien names, determined to pronounce them accurately. Kta was horrified at first to believe his parents shared a common house name, and Kurt angrily, almost tearfully, explained human customs of marriage, for he was exhausted and this interrogation was prolonging his misery.

“I shall explain to the Ancestors,” said Kta. “Don’t be afraid. Elas is a house patient with strangers and strangers’ ways.”

Kurt bowed his head, not to have any further argument. He was tolerated for the sake of Kta, a matter of Kta’s honor.

He was cold when Kta and Mim left him alone, and crawled between the cold sheets, unable to stop shivering.

He was one of a kind, save for Djan, who hated him.

And among nemet, he was not even hated. He was inconvenient.

Food arrived late that evening, brought by Hef; Kurt dragged his aching limbs out of bed and fully dressed, which would not have been his inclination, but he was determined to do nothing to lessen his esteem in the eyes of the nemet.

Then Kta arrived to share dinner with him in his room.

“It is custom to take dinner in the rhmei,all Elas together,” Kta explained, “but I teach you, here. I don’t want you to offend against my family. You learn manners first.”

Kurt had borne with much. “I have manners of my own,” he cried, “and I’m sorry if I contaminate your house. Send me back to the Afen, to Djan—it’s not too late for that.” And he turned his back on the food and on Kta, and walked over to stand looking out the dark window. It dawned on him that sending him to Elas had been Djan’s subtle cruelty; she expected him back, broken in pride.

“I meant no insult,” Kta protested.

Kurt looked back at him, met the dark, foreign eyes with more directness than Kta had ever allowed him. The nemet’s face was utterly stricken.

“Kurt-ifhan,” said Kta, “I didn’t wish to cause you shame. I wish to help you,—not putting you on display in the eyes of my father and my mother. It is your dignity I protect.”

Kurt bowed his head and came back, not gladly. Djan was in his mind, that he would not run to her for shelter, giving up what he had abjectly begged of her. And perhaps too she had meant to teach the house of Elas its place, estimating it would beg relief of the burden it had asked. He submitted. There were worse shames than sitting on the floor like a child and letting Kta mold his unskilled fingers around the strange tableware.

He quickly knew why Kta had not permitted him to go downstairs. He could scarcely feed himself and, starving as he was, he had to resist the impulse to snatch up food in disregard of the unfamiliar utensils. Drink with the left hand only, eat with the right, reach with the left, never the right. The bowl was lifted almost to the lips, but it must never touch. From the almost bowl-less spoon and thin skewer he kept dropping bites. The knife must be used only left-handed.

Kta was cautiously tactful after his outburst, but grew less so as Kurt recovered his sense of humor. They talked, between instructions and accidents, and afterward, over a cup of tea. Sometimes Kta asked him of human customs, but he approached any difference between them with the attitude that while other opinions and manners were possible, they were not so under the roof of Elas.

“If you were among humans,” Kurt dared ask him finally, “what would you do?”

Kta looked as if the idea horrified him, but covered it with a downward glance. “I don’t know. I know only Tamurlin.”

“Did not—” he had tried for a long time to work toward this question,—“did not Djan-methi come with others?”

The frightened look persisted. “Yes. Most left. Djan-methi killed the others.”

He quickly changed the subject and looked as if he wished he had not been so free of that answer, though he had given it straightly and with deliberation.

They talked of lesser things, well into the night, over many cups of tea and sometimes of telise,until from the rest of Elas there was no sound of people stirring and they must lower their voices. The light was exceedingly dim, the air heavy with the scent of oil from the lamps. The telisemade it close and warm. The late hour clothed things in unreality.

Kurt learned things, almost all simply family gossip, for Djan and Elas were all in Nephane that they both knew, and Kta, momentarily so free with the truth, seemed to have remembered that there was danger in it. They spoke instead of Elas.

Nym had the authority in the household as the lord of Elas; Kta had almost none, although he was over thirty (he hardly looked it) and commanded a warship. Kta would be under Nym’s authority as long as Nym lived; the eldest male was lord in the house. If Kta married, he must bring his bride to live under his father’s roof. The girl would become part of Elas, obedient to Kta’s father and mother as if she were born to the house. So Aimu was soon to depart, betrothed to Kta’s lieutenant Bel t’Osanef. They had been friends since childhood, Kta and Bel and Aimu.

Kta owned nothing. Nym controlled the family wealth, and would decide how and whom and when his two children must marry, since marriage determined inheritances. Property passed from father to eldest son undivided, and the eldest then assumed a father’s responsibility for all lesser brothers and cousins and unmarried women in the house. A patriarch like Nym always had his rooms to the right of the entry, a custom, Kta explained, derived from more warlike times, when a man slept at the threshold to defend his home from attack. Grown sons occupied the ground floor for the same reason. This room that Kurt now held as a guest had been Kta’s when he was a boy.

And the matriarch, in this case Kta’s mother Ptas, although it had been the paternal grandmother until quite recently, had her rooms behind the base wall of the rhmei.She was the guardian of most religious matters of the house. She tended the holy fire of the phusmeha,supervised the household and was second in authority to the patriarch.

Of obeisance and respect, Kta explained, there were complex degrees. It was gross disrespect for a grown son to come before his mother without going to his knees, but when he was a boy this difference was not paid. The reverse was true with a son and his father: a boy knelt to his father until his coming-of-age, then met him with the slight bow of almost-equals if he were eldest, necessary obeisances deepening as one went down the ranks of second son, third son, and so on. A daughter, however, was treated as a beloved guest, a visitor the house would one day lose to a husband; she gave her parents only the obeisance of second-son’s rank, and showed her brothers the same modest formality she must use with strangers.

But of Hef and Mim, who served Elas, was required only the obeisance of equals, although it was their habit to show more than that on formal occasions.

“And what of me?” Kurt asked, dreading to ask. “What must I do?”

Kta frowned. “You are guest, mine; you must be equal with me. But,” he added nervously, “it is proper in a man to show greater respect than necessary sometimes. It does not hurt your dignity; sometimes it makes it greater. Be most polite to all. Don’t—make Elas ashamed. People will watch you—thinking they will see a Tamuruin nemet dress. You must prove this is not so.”

“Kta,” Kurt asked, “—am I a man—to the nemet?”

Kta pressed his lips together and looked as if he earnestly wished that question had gone unasked.

“I am not, then,” Kurt concluded, and was robbed even of anger by the distress on Kta’s face.

“I have not decided,” Kta said. “Some—would say no. It is a religious question. I must think.—But I have a liking for you, Kurt, even if you arehuman.”

“You have been very good to me.”

There was silence between them. In the sleeping house there was no sound at all. Kta looked at him with a directness and a pity that disquieted him.

“You are afraid of us,” Kta observed.

“Did Djan make you my keeper only because you asked, or because she trusts you in some special way—to watch me?”

Kta’s head lifted slightly. “Elas is loyal to the Methi. But you are guest.”

“Are nemet who speak human language so common? You are very fluent, Kta. Mim is. Your—readiness to accept a human into your house—is that not different from the feelings of other nemet?”

“I interpreted for the umaniwhen they first came to Nephane. Before that, I learned of Mim, and Mim learned because she was prisoner of the Tamurlin. What evil do you suspect? What is the quarrel between you and Djan-methi?”

“We are of different nations, an old, old war. Don’t get involved, Kta, if you did only get into this for my sake. If I threaten the peace of your house—or your safety—tell me. I’ll go back. I mean that.”

“This is impossible,” said Kta. “No. Elas has never dismissed a guest.”

“Elas has never entertained a human.”

“No,” Kta conceded. “But the Ancestors when they lived were reckless men. This is the character of Elas. The Ancestors guide us to such choice, and Nephane and the Methi cannot be much surprised at us.”

The nemet’s lives were uniformly tranquil. Kurt endured a little more than four days of the silent dim halls and the hushed voices and the endless bowing and refraining from untouchable objects and untouchable persons before he began to feel his sanity slipping.

On that day he went upstairs and locked the door, despite Kta’s pleas to explain his behavior. He shed a few tears, fiercely and in the privacy of his room, and curtained the window so he did not have to look out upon the alien world. He sat in the dark until the night came, then he slipped quietly downstairs and sat in the empty rhmei,trying to make his peace with the house.

Mim came. She stood and watched him silently, hands twisting nervously before her.

At last she pattered on soft feet over to the chairs and gathered up one of the fleeces, and brought it to the place where he sat on the cold stone. She laid it down beside him, and chanced to meet his eyes as she straightened. Hers questioned, greatly troubled, even frightened.

He accepted the offered truce between them, edged onto the welcome softness of the fleece.

She bowed very deeply, then slipped out again, extinguishing the lights one by one as she left, save only the phusmeba,that burned the night long.

Kta also came out to him, but only looked as if to see that he was well. Then he went away, and left the door of his room open the night long.

Kurt rose up in the morning and paused in Kta’s doorway to give him an apology. The nemet was awake and arose in some concern, but Kurt did not find words adequate to explain his behavior. He only bowed in respect to the nemet, and Kta to him, and he went up to his own room to prepare for the decency of breakfast with the family.

Gentle Kta. Soft-spoken, seldom angry, he stood above six feet in height and was physically imposing; but it was uncertain whether Kta had ever laid aside his dignity to use force on anyone. It was an increasing source of amazement to Kurt that this intensely proud man had vaulted a ship’s rail in view of all Nephane to rescue a drowning human, or sat on the dock and helped him amid his retching illness. Nothing seemed to ruffle Kta for long. He met frustration by retiring to meditate on the problem until he had restored himself to what he called yhia,or balance, a philosophy evidently adequate even in dealing with humans.

Kta also played the aos,a small harp of metal strings, and sang with a not unpleasant voice, which was the particular pleasure of lady Ptas upon the quiet evenings,—sometimes light, quick songs that brought laughter to the rhmei,—sometimes very long ones that were interrupted with cups of teliseto give Kta’s voice a rest,—songs to which all the house listened in sober silence, plaintive and haunting melodies of anharmonic notes.

“What do you sing about?” Kurt asked him afterward. They sat in Kta’s room, sharing a late cup of tea. It was their habit to sit and talk late into the night. It was almost their last. The two weeks were almost spent. Tonight he wanted very much to know the nemet, not at all sure that he would have a further chance. It had been beautiful in the rhmei,the notes of the aos,the sober dignity of Nym, the rapt face of lady Ptas, Aimu and Mim with their sewing, Hef sitting to one side and listening, his old eyes dreaming.

The stillness of Elas had seeped into his bones this night, a timeless and now fleeting time which made all the world quiet. He had striven against it. Tonight, he listened.

“The song would mean nothing to you,” Kta said. “I can’t sing it in human words.”

“Try,” said Kurt.

The nemet shrugged, gave a pained smile, gathered up the aosand ran his fingers over the sensitive strings, calling forth the same melody. For a moment he seemed lost, but the melody grew, rebuilt itself in all its complexity.

“It is our beginning,” said Kta, and spoke softly, not looking at Kurt, his fingers moving on the strings like a whisper of wind, as if that was necessary for his thoughts.

There was water. From the sea came the nine spirits of the elements, and greatest were Ygr the earthly and Ib the celestial. From Ygr and Ib came a thousand years of begettings and chaos and wars of elements, until Las who was light and Mur who was darkness, persuaded their brother-gods Phan the sun and Thael the earth to part.

So formed the first order. But Thael loved Phan’s sister Ti, and took her. Phan in his anger killed Thael, and of Thael’s ribs was the earth. Ti bore dead Thael a son, Aem.

Ten times a thousand years came and passed away.

Aem came to his age, and Ti saw her son was fair.

They sinned the great sin. Of this sin came Yr,