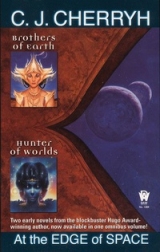

Текст книги "At the Edge of Space (Brothers of Worlds; Hunter of Worlds)"

Автор книги: C. J. Cherryh

Жанр:

Космическая фантастика

сообщить о нарушении

Текущая страница: 7 (всего у книги 36 страниц)

“Bel,” exclaimed Aimu, “you cannot think these things: you are upset. Your mind will change.”

“No, it has never been different. I have always known it is an Indras world, and that my sons and my sons’ sons will grow more and more Indras, until they will not understand the mind of the likes of me. I love you, Aimu, and I do not repent my choice, but perhaps now you do. I do not think your well-bred Indras friends would think you disgraced if you broke our engagement. Most would be rather relieved you had come to your senses, I think.”

Kta’s back stiffened. “Have a care, Bel. My sister has not deserved your spite. Anything you may care to say or do with me—that is one matter; but you go too far when you speak that way to her.”

“I beg pardon,” Bel murmured, and glanced at Aimu. “We were friends before we were betrothed, Aimu; I think you know how to understand me, and I fear you may come to regret me and our agreement. A Sufaki house will be a strange enough place for you; I would not see you hurt.”

“I hold by our agreement,” said Aimu. Her face was pale, her breathing quick. “Kta, take no offense with him.”

Kta lowered his eyes, made a sign of unwilling apology, then glanced up. “What do you want of me, Bel?”

“Your influence. Speak to your Indras friends; make them understand.”

“Understand what? That they must cease to be Indras and imitate Sufaki ways? This is not the way the world is ordered, Bel. And as for violence, if it comes, it will not come from the Indras—that is not our way and it never has been. Persuasion is something you must use on your people.”

“You have created a Shan Tefur,” said Bel, “and he finds many others like him. Now we who have been friends of the Indras do not know what to do.” Bel was trembling. He clasped his hands, elbows on his knees. “There is no more peace, Kta. But let no Indras answer violence with violence, or there will be blood flowing in the streets come the month of Nermotai and the holy days.—Your pardon, my friends.” He rose, shaking out his robes. “I know the way out of Elas. You do not have to lead me. Do what you will with what I have told you.”

“Bel,” said Aimu, “Elas will not put you off for the sake of Shan t’Tefur’s threats.”

“But Osanef has to fear those threats. Do not expect me to be seen here again in the near future. I do not cease to regard you as my friends. I have faith in your honor and your good judgment, Kta. Do not fail my hopes.”

“Let me go with him to the door,” said Aimu, though what she asked violated all custom and modesty, “Kta, please.”

“Go with him,” said Kta. “Bel, my brother, we will do what we can. Be careful for yourself.”

11

Nephane was well named the city of mists. They rolled in and lasted for days as the weather grew warmer, making the cobbled streets slick with moisture. Ships crept carefully into harbor, the lonely sound of their bells occasionally drifting up the height of Nephane through the still air. Voices distantly called out in the streets, muted.

Kurt looked back, anxious, wondering if the sudden hush of footsteps that had been with him ever since the door of Elas meant an end of pursuit.

A shadow appeared near him. He stumbled off the edge of the unseen curb and caught his balance, fronted by several others who appeared, cloaked and anonymous, out of the grayness. He backed up and halted, warned by a scrape of leather on stone: others were behind him. His belly tightened, muscles braced.

One moved closer. The whole circle narrowed. He ducked, darted between two of them and ran. Soft laughter pursued him, nothing more. He did not stop running.

The Afen gate materialized out of the fog. He pushed the heavy gate inward. He had composed himself by the time he reached the main door. The guards stayed inside on this inclement day, and only looked up from their game, letting him pass,—alert enough, but, Sufaki-wise, careless of formalities. He shrugged the ctanback to its conventional position under his right arm and mounted the stairs. Here the guards came smartly to attention: Djan’s alien sense of discipline: and they for once made to protest his entry.

He pushed past and opened the door, and one of them then hurried into the room and back into the private section of the apartments, presumably to announce his presence.

He had time enough to pace the floor, returning several times to the great window in the neighboring room. Fog-bound as the city was, he could scarcely make out anything but Haichema-tleke, Maiden Rock, the crag that rose over the harbor, against whose shoulder the Afen and the Great Families’ houses were built. Gray and ghostly in a world of pallid white, it seemed the cloud-city’s anchor to solid earth.

A door hissed upon the other room and he walked back. Djan was with him. She wore a silver-green suit, thin, body-clinging stuff. Her coppery hair was loose, silken and full of static. She had a morning look about her, satiated and full of sleep.

“It’s near noon,” he said.

“Ah,” she murmured, and looked beyond him to the window. “So we’re bound in again. Cursed fog. I hate it.—Like some breakfast?”

“No.”

Djan shrugged and from utensils in the carved wood cabinet prepared tea, instantly heated. She offered him a cup: he accepted, nemet-schooled. It gave one something to do with the hands.

“I suppose,” she said when they were seated, “that you didn’t come here in this weather and wake me out of a sound sleep to wish me good morning.”

“I almost didn’t make it here; which is the situation I came to talk to you about. The neighborhood of Elas isn’t safe even by day. There are Sufaki hanging about, who have no business there.”

“The quarantine ordinances were repealed, you know. I can’t forbid their being there.”

“Are they your men? I’d be relieved if I thought they were. That is,—if yours and Shan t’Tefur’s aren’t one and the same, and I trust that isn’t the case. For a long time it’s been at night; since the first of Nermotai, it’s been even by day.”

“Have they hurt anyone?”

“Not yet. People in the neighborhood stay off the streets. Children don’t go out. It’s an ugly atmosphere, I don’t know whether it’s aimed at me in particular or Elas in general, but it’s a matter of time before something happens.”

“You haven’t done anything to provoke this?”

“No. I assure you I haven’t. But this is the third day of it. I finally decided to chance it. Are you going to do anything?”

“I’Il have my people check it out, and if there’s cause I’ll have the people removed.”

“Well, don’t send Shan t’Tefur on the job.”

“I said I would see to it. Don’t ask favors and then turn sharp with me.”

“I beg your pardon. But that’s exactly what I’m afraid you’ll do,—trust things to him.”

“I am not blind, my friend. But you’re not the only one with complaints. Shan’s life has been threatened. I hear it from both sides.”

“By whom?”

“I don’t choose to give my sources. But you know the Indras houses and you know the hard-line conservatives. Make your own guess.”

“The Indras are not a violent people. If they said it, it was more in the sense of a sober promise than a threat, and that in consideration of the actions he’s been urging. You’ll have riots in the streets if Shan t’Tefur has his way.”

“I doubt it. See, I’m being perfectly honest with you: a bit of trust. Shan uses that apparent recklessness as a tactic; but he is an intelligent man, and his enemies would do well to reckon with that.”

“And is he responsible for the late hours you’ve been keeping?”

Her eyes flashed suddenly, amused. “This morning, you mean?”

“Either you’re naive or think he is. That is a dangerous man, Djan.”

The humor died out of her eyes. “Well, you’re one to talk about the dangers of involvement with the nemet.”

“You’re facing the danger of a foreign war and you need the goodwill of the Indras Families; but you keep company with a man who talks of killing Indras and burning the fleet.”

“Words. If the Indras are concerned, good. I didn’t create this situation: I walked into it as it is. I’m trying to hold this city together. There will be no war if it stays together. And it will stay together if the Indras come to their senses and give the Sufaki justice.”

“They might, if Shan t’Tefur were out of it. Send him on a long voyage somewhere. If he stays in Nephane and kills someone, which is likely, sooner or later, then you’re going to have to apply the law to him without mercy. And that will put you in a difficult position, won’t it?”

“Kurt.” She put down the cup. “Do you want fighting in this city? Then let’s just start dealing like that with both sides, one ultimatum to Shan to get out, one to Nym, to be fair—and there won’t be a stone standing in Nephane when the smoke clears.”

“Try closing your bedroom to Shan t’Tefur,” he said, “for a start. Your credibility among the Families is in rags as long as you’re Shan t’Tefur’s mistress.”

It hurt her. He had thought it could not, and suddenly he perceived she was less armored than he had believed.

“You’ve given your advice,” she said. “Go back to Elas.”

“Djan—”

“Out.”

“Djan, you talk about the sanctity of local culture, the balance of powers, but you seem to think you can pick and choose the rules you like. In some measure I don’t blame Shan t’Tefur. You’ll be the death of him before you’re done, playing on his ambitions and his pride and then refusing to abide by the customs he knows. You know what you’re doing to him? You know what it is to a man of the nemet that you take for a lover and then play politics with him?”

“I told him fairly that he had no claim on me. He chose.”

“Do you think a nemet is really capable of believing that? And do you think that he believes now he had no just claim on the Methi’s loyalty, whatever he does in your name? He’ll push you someday to the point where you have to choose. He’s not going to let you have your own way with him forever.”

“He knows how things are.”

“Then ask yourself why he comes running when you call him to your bed, and if you discover it’s not your considerable personal attractions, don’t say I didn’t warn you. A nemet doesn’t take that kind of treatment, not without some compelling reason. If this is your method of controlling the Sufaki, you’ve picked the wrong man.”

“Nevertheless”—her voice acquired a tremor that she tried to suppress—“my mistakes are my choice.”

“Will that undo someone’s dying?”

“My choice,” she insisted, with such intensity that it gave him pause.

“You’re not in love with him?” It was question, and plea at once. “You’re too sensible for that, Djan. You said yourself this world doesn’t give you that choice. You’d kill him or he’d be the death of you sooner or later.”

She shrugged, and the old cynical bitterness that he trusted was back. “I was conceived to serve the state. Doing so is an unbreakable habit. Other people—like you, my friend,—normal people—serve themselves. Relationships like serving self, serving—others—are outside my experience. I thought I was selfish, but I begin to see there are other dimensions to that word. I find personal relations tedious, these games of me and thee. I enjoy companionship. I—love you. I love Shan. That is not the same as: I love Nephane. This city is mine; it is mine.Spare me your appeals to personal affection. I would destroy either of you if I were clearly convinced it was necessary to the survival of this city. Remember that.”

“I am sorry for you,” he said.

“Get out.”

Tears gathered to her eyes, belying everything she had said. She struggled for dignity, lost; the tears spilled free, her lips trembling into sobs. She clenched her jaw, turned her face and gestured for him to go.

“I am sorry,” he said, this time with compassion, at which she shook her head and kept her back to him until the spasm had passed.

He took her arms, trying to comfort her, and felt guilty because of Mim; but he felt guilty because of Djan too, and feared that she would not forgive him for witnessing this. She had been here longer, a good deal longer than he. He well knew the nightmare, waking in the night, finding that reality had turned to dreams and the dream itself was as real as the stranger beside him, looking into a face that was not human, perceiving ugliness where a moment before had been beauty.

“I am tired,” she said, leaning against him. Her hair smelled of these exotic on this world, lab-born, like Djan—perfumes like home, from a thousand star-scattered worlds the nemet had never dreamed of. “Kurt, I work, I study, I try. I am tired to death.”

“I would help you,” he said, “if you would let me.”

“You have loyalties elsewhere,” she said finally. “I wish I’d never sent you to Elas, to learn to be nemet, to belong to them. You want things for your cause, he wants things for his. I know all that, and occasionally I want to forget it. It’s a human weakness. Am I not allowed just one? You came here asking favors. I knew you would, sooner or later.”

“I would never ask you deceitfully, to do you harm. I owe you, as I owe Elas.”

She pushed back from him. “And I hate you most when you do that. Your concern is touching, but I don’t trust it.”

“Nephane is killing you.”

“I can manage.”

“Probably you can,” he said. “But I would help you.”

“Ah, as Shan helps me. But you don’t like it when it’s the opposition, do you? Blast you, I gave you leave to marry and you’ve done it, you’ve made your choice, however tempting it was to—”

She did not finish. He suddenly found reason for uneasiness in that omission. Djan was not one to let words fly carelessly.

“When I came here,” he said, “whenever I come, I try to leave my relations with Elas at the door. You’ve never tried to make me go against them; and I do not use you, Djan.”

“Your little Mim,” said Djan. “What is she like? Typical nemet?”

“Not typical.”

“Elas is using you,” she said. “Whether you know it or not, that is so. I could still stop that. I could simply have you given quarters here in the Afen. No arrest decree has Upei review. Thatpower of a Methi is absolute.”

She actually considered it. He went cold inside, realizing that she could and would do it, and knew suddenly that she meant this for petty revenge, taking his peace of mind in retaliation for her humiliation of a moment ago. Pride was important to her.

“Do you want me to ask you not to do that?” he asked.

“No,” she said. “If I decide to do that, I will do it, and if I do not, I will not. What you ask has nothing to do with it. But I would advise you and Elas to remain quiet.”

12

The fog did not go out. It held the city the next morning, the faint sound of warning bells drifting up from the harbor. Kurt opened his eyes on the grayness outside the window, then looked toward the foot of the bed where Mim sat combing her long hair, black and silken and falling to her waist when unbound. She looked back at him and smiled, her alien and wonderfully lovely eyes soft with warmth.

“Good morning, my lord.”

“Good morning,” he murmured.

“The mist is still with us,” she said. “Hear the harbor bells?”

“How long can this last?”

“Sometimes many days when the seasons are turning,—especially in the spring.” She flicked several strands of hair apart and began with quick fingers to plait them into a thin braid. Then she would sweep most of her hair up to the crown of her head, fasten it with pins and combs, an intricate and fascinating ritual daily performed and nightly undone. He liked watching her. In a matter of moments she began the next braid.

“We say,” Mim commented, “that the mist is a cloak of the imiine,the sky-sprite Nue, when she comes to visit earth and walk among men. She searches for her beloved, that she lost long ago in the days when godkings ruled. He was a mortal man who offended one of the godkings, a son of Yr whose name was Knyha;—and, poor man, he was slain by Knyha, and his body scattered over all the shore of Nephane so that Nue would not know what had become of him. She still searches and walks the land and the sea and haunts the rivers, especially in the springtime.”

“Do you truly think that?” Kurt asked, not sarcastically: one could not be that with Mim. He was prepared to mark it down to be remembered with all his heart if she wished him to.

Mim smiled. “I do not, not truly. But it is a beautiful story, is it not, my lord? There are truths and there are truths, my lord Kta would say, and there is Truth itself, the yhia,—and since mortals cannot always reason all the way to Truth, we find little truths that are right enough on our own level. But you are very wise about things. I think you really might know what makes the mist come. Is it a cloud that sits down upon the sea, or is it born in some other way?”

“I think,” said Kurt, “that I like Nue best. It sounds better than water vapor.”

“You think I am silly and you cannot make me understand.”

“Would it make you wiser if you knew where fog comes from?”

“I wish that I could talk to you about all the things that matter to you.”

He frowned, realizing that she was in earnest. “You matter. This place, this world matters to me, Mim.”

“I know so very little.”

“What do you want to know?”

“Everything.”

“Well, you owe me breakfast first.”

Mim flashed a smile, put in the last combs and finished her hair with a pat. She slipped on the chatem,the overdress with the four-paneled split skirt which fitted over the gossamer drapery of the pelan,the underdress. The chatem,high-collared and long-sleeved, tight and restraining in the bodice,—rose and beige brocade, over a rose pelan.There were many buttons up either wrist and up the bodice to the collar. She patiently began the series of buttons.

“I will have tea ready by the time you can be downstairs,” she said. “I think Aimu will have been—”

There was a deep hollow boom over the city, and Kurt glanced toward the window with an involuntary oath. It was the sighing note of a distant gong.

“ Ai,” said Mim. “ Intaem-Inta.That is the great temple. It is the beginning of Cadmisan.”

The gong moaned forth again through the fog-stilled air, measured, four times more. Then it was still, the last echoes dying.

“It is the fourth of Nermotai,” said Mim, “the first of the Sufak holy days. The temple will sound the Intaevery morning and every evening for the next seven days, and the Sufaki will make prayers and invoke the Intain,the spirits of their gods.”

“What is done there?” Kurt asked.

“It is the old religion which was here before the Families. I am not really sure what is done, and I do not care to know. I have heard that they even invoke the names of godkings in Phan’s own temple; but we do not go there, ever. There were old gods in Chteftikan, old and evil gods from the First Days, and once a year the Sufaki call their names and pay them honor, to appease their anger at losing this land to Phan. These are beings we Indras do not name.”

“Bel said,” Kurt recalled, “that there could be trouble during the holy days.”

Mim frowned. “Kurt, I would that you take special care for your safety, and do not come and go at night during this time.”

It hit hard. Mim surely spoke without reference to the Methi, at least without bitterness: if Mim accused, he knew well that Mim would say so plainly. “I do not plan to come and go at night,” he said. “Last night—”

“It is always dangerous,” she said with perfect dignity, before he would finish, “to walk abroad at night during Cadmisan. The Sufak gods are earth-spirits, Yr-bred and monstrous. There is wild behavior and much drunkenness.”

“I will take your advice,” he said.

She came and touched her fingers to his lips and to his brow, but she took her hand from him when he reached for it, smiling. It was a game they played.

“I must be downstairs attending my duties,” she said. “Dear my husband, you will make me a reputation for a licentious woman in the household if you keep making us late for breakfast.—No!—dear my lord, I shall see you downstairs at morning tea.”

“Where do you think you are going?”

Mim paused in the dimly lit entry hall, her hands for a moment suspending the veil over her head as she turned. Then she settled it carefully over her hair and tossed the end over her shoulder.

“To market, my husband.”

“Alone?”

She smiled and shrugged. “Unless you wish to fast this evening. I am buying a few things for dinner. Look you, the fog has cleared, the sun is bright, and those men who were hanging about across the street have been gone since yesterday.”

“You are not going alone.”

“Kurt, Kurt, for Bel’s doom-saying? Dear light of heaven, there are children playing outside, do you not hear? And should I fear to walk my own street in bright afternoon? After dark is one thing, but I think you take our warnings much too seriously.”

“I have my reasons, Mim.”

She looked up at him in most labored patience. “And shall we starve? Or will you and my lord Kta march me to market with drawn weapons?”

“No, but I will walk you there and back again.” He opened the door for her, and Mim went out and waited for him, her basket on her arm, most obviously embarrassed.

Kurt nervously scanned the street, the recesses where of nights t’Tefur’s men were wont to linger. They were indeed gone. Indras children played at tag. There was no threat—no presence of the Methi’s guards either, but Djan never did move obviously: he had no difficulty returning to Elas late, probably, he thought with relief, she had taken measures.

“Are you sure,” he asked Mim, “that the market will be open on a holiday?”

She looked up at him curiously as they started off together. “Of course, and busy. I put off going, you see, these several days with the fog and the trouble on the streets, and I am sorry to cause you this trouble, Kurt, but we really are running out of things and there could be the fog again tomorrow, so it is really better to go today. I have some sense, after all.”

“You know I could quite easily walk down there and buy what you need for supper, and you would not need to go at all.”

“ Ai,but Cadmisan is such a grand time in the market, with all the country people coming in, and the artists, and the musicians—besides,” she added, when his face remained unhappy, “dear husband, you would not know what you were buying or what to pay. I do not think you have ever handled our coin. And the other women would laugh at me and wonder what kind of wife I am to make my husband do my work, or else they would think I am such a loose woman that my husband would not trust me out of his sight.”

“They can mind their own business,” he said, disregarding her attempt at levity; and her small face took on a determined look.

“If you go alone,” she said, “the fact is that folk will guess Elas is afraid, and this will lend courage to the enemies of Elas.”

He understood her reasoning, though it comforted him not at all. He watched carefully as their downhill walk began to take them out of the small section of aristocratic houses surrounding the Afen and the temple complex. But here in the Sufaki section of town, people were going about business as usual. There were some men in the Robes of Color, but they walked together in casual fashion and gave them not a passing glance.

“You see,” said Mim, “I would have been quite safe.”

“I wish I was that confident.”

“Look you, Kurt, I know these people. There is lady Yafes, and that little boy is Edu t’Rachik u Gyon—the Rachik house is very large. They have so many children it is a joke in Nephane. The old man on the curb is t’Pamchen. He fancies himself a scholar. He says he is reviving the old Sufak writing and that he can read the ancient stones. His brother is a priest, but he does not approve of the old man. There is no harm in these people. They are my neighbors. You let t’Tefur’s little band of pirates trouble you too much. T’Tefur would be delighted to know he upset you. That is the only victory he dares to seek as long as you give him no opportunity to challenge you.”

“I suppose,” Kurt said, unconvinced.

The street approached the lower town by a series of low steps down a winding course to the defense wall and the gate. Thereafter the road went among the poorer houses, the markets, the harborside. Several ships were in port, two broad-beamed merchant vessels and three sleek galleys, warships with oars run in or stripped from their locks, yards without sails, the sounds of carpentry coming loudly from their decks, one showing bright new wood on her hull.

Ships were being prepared against the eventuality of war. Tavi,Kta’s ship, had been there; she had had her refitting and had been withdrawn to the outer harbor, a little bay on the other side of Haichema-tleke. That reminder of international unease, the steady hammering and sawing, underlay all the gaiety of the crowds that thronged the market.

“That is a ship of Ilev, is it not?” Kurt asked, pointing to the merchantman nearest, for he saw what appeared to be the white bird that was emblematic of that house as the figurehead.

“Yes,” said Mim. “But the one beside it I do not recognize. Some houses exist only in the Isles. Lord Kta knows them all, even the houses of Indresul’s many colonies. A captain must know these things. But of course they do not come to Nephane. This one must be a trader that rarely comes, perhaps from the north, near the Yvorst Ome, where the seas are ice.”

The crowd was elbow-to-elbow among the booths. They lost sight of the harbor, and nearly of each other. Kurt seized Mim’s arm, which she protested with a shocked look: even husband and wife did not touch publicly.

“Stay with me,” he said, but he let her go. “Do not leave my sight.”

Mim walked the maze of aisles a little in front of him, occasionally pausing to admire some gimcrack display of the tinsmiths, intrigued by the little fish of jointed scales that wiggled when the wind hit their fins.

“We did not come for this,” Kurt said irritably. “Come, what would you do with such a thing?”

Mim sighed, a little piqued, and led him to that quarter of the market where the farmers were, countrymen with produce and cheeses and birds to sell, fishermen with the take from their nets, butchers with their booths decorated with whole carcasses hanging from hooks.

Mim deplored the poor quality of the fish that day, disappointed in her plans—selected from a vegetable seller some curious yellow corkscrews called lat,and some speckled orange ones called gillybai.She knew the vegetable seller’s wife, who congratulated her on her recent marriage, marveled embarrassingly over Kurt—she seemed to shudder slightly, but showed brave politeness—then became involved in a long story about a mutual acquaintance’s daughter’s child.

It was woman’s talk. Kurt stood to one side, forgotten, and then, sure that Mim was safe among people she knew and not willing to seem utterly the tyrant,—withdrew a little. He looked at some of the other tables in the next booth, somewhat interested in the alien variety of the fish and the produce—some of which, he reflected with unease, he had undoubtedly eaten without knowing its uncooked appearance. Much of the seafood was not in the least appealing to Terran senses.

From the harbor there came the steady sound of hammering, reechoing off the walls in insane counterpoint to the noise of the many colored crowds.

Someone jostled him. He looked up into the unsmiling face of a Sufaki in Robes of Color. The man said nothing. Kurt made a slight bow of apology, unanswered, and turned about to go after Mim.

Another man blocked his way. Kurt tried to step around him. The Sufaki moved in front of him with sullen threat in his narrow eyes. Another appeared to his left, crowding him back to the right.

He moved suddenly, trying to slip past them. They cut him off from Mim. He could not see her any longer. The noisy crowds surged between. He dared not start something with Mim near, where she could be hurt.

They forced him continually in one direction, toward a gap between the booths where they jammed up against a warehouse. He saw the alley and broke for it.

Others met him at the turning ahead, pursuit hot behind. He had expected it and hit the opposition without hesitation. He avoided a knife and kicked its owner, who screamed in agony,—struck another in the face and a third in the groin before those behind overhauled him.

A blow landed between his shoulders and against his head, half blinding him. He fell under a weight of struggling bodies, pinned while more than one of them wrenched his arms back and tied his wrists.

He had broken one man’s arm. He saw that with satisfaction as they hauled him to his feet and tried to aid their own injured.

Then they seized him by either arm and hurried him deeper into the alley.

The backways of Nephane were a maze of alien geometry, odd-shaped buildings jammed incredibly into the S-curve of the main street, fronting outward in decent order while their rear portions formed a labyrinthine tangle of narrow alleyways and contiguous walls. Kurt quickly lost track of the way they had come.

They reached the back door of a warehouse, thrust Kurt inside and entered the dark with him, closing the door so that all the light was from the little door aperture.

Kurt scrambled to escape into the shadows, sure now that he would be found some time later with his throat cut and no proof who his murderers had been.

They seized him before he could run more than a few steps, hurried him to the dusty floor and slipped a cord about his ankle. Finally, despite his kicking and heaving, they succeeded in lashing both his ankles together. Then they forced his jaws apart and thrust a choking wad of cloth into his mouth, tying it in place with a violence that cut his face.

“Get a light,” one said.

The door opened before that was done. Their comrades had joined them, bringing the man with the broken arm. When the light was lit they attended to the setting of the arm, with screams they tried to muffle.

Kurt wriggled over against some bales of canvas, nerves raw to every outcry from the injured man. They would repay him for that, he was sure, before they disposed of him.

It was the human thing to do. In this respect he hoped they were different.