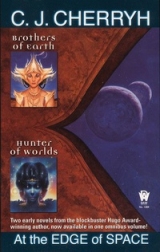

Текст книги "At the Edge of Space (Brothers of Worlds; Hunter of Worlds)"

Автор книги: C. J. Cherryh

Жанр:

Космическая фантастика

сообщить о нарушении

Текущая страница: 22 (всего у книги 36 страниц)

“I have—come a long way, a very long way from home. I don’t even know where I am or why. I know—” No, no, not accusation; soft with him, soft, don’t make him angry.“I know that you are being kind, that I—am being treated well—” Cages were in his mind; he thought them only out of sight on the other side of the wall, shrieks and hideous noise and darkness. At least he looks human,the second level ran. Looks. Looks. Seems. Isn’t. God, help me.“Aiela, I—understand. I am grateful, Aiela—”

Daniel tried desperately to screen in his fear. It was a terrible effort. Under it all, nonverbal, there was fear of a horrible kind, fear of oblivion, fear of losing his mind altogether; but he would yield, he would merge, anything, anything but lose this chance. It was dangerous. It pulled at both of them. Aiela screened briefly, stopping it.

“I don’t know how to help you,” Aiela told him gently. “But I assure you I don’t want to harm you. You are safe. Be calm.”

Information—they want—home came to mind, far distant, a world of red stone and blue skies. The memory met Aiela’s surmise, the burrows of amaut worlds, human laborers, and confused Daniel greatly. Past or future,Daniel wondered. Mine? Is this mine? Is this what I’m going to?

Aiela drew back, trying to sort the human thoughts from his own. Nausea assailed him. The human’s terrors began to seem his, sinister things, alien; and the amaut were at the center of all the nightmares.

“How did you come here, then?” Aiela asked. “Where did you come from, if not from the amaut worlds?”

And where is here and what are you?the human responded inwardly; but in the lightning-sequencing of memory, answers came, random at first, then deliberate—remembrances of that little world that had been home: poverty, other humans, anger, a displaced folk yearning toward a green and beautiful home that had no resemblance to the red desolation in which they now lived: an urge toward ships, and voyaging, homecoming and revenge.

Years reeled backward and forward again: strange suns, worlds, service in many ships, machinery appallingly primitive, backbreaking labor—but among humans, human ships, human ports, scant resources, sordid pleasures. Above all a regret for that sandy homeland, and finally a homecoming—to a home dissolved, a farm gone to dust; more port cities, more misery, a life without ties and without purpose. The thoughts ran aimlessly into places so alien they were madness.

These were not the Esliph worlds. Amaut did not belong there. Human space, then, human worlds, where kalliran and amaut trade had never gone.

Amaut.Daniel’s mind seized on the memory with hate. Horrible images of death, bodies twisted, stacked in heaps—prisoners—humans—gathered into camps, half-starved and dying, others hunted, slaughtered horribly and hung up for warnings, the hunters humankind too; but among them moved dark, large-eyed shapes with shambling gait and leering faces—amaut seen through human eyes. Events tumbled one over the other, and Aiela resisted, unknowing what terrible place he was being led next; but Daniel sent, forcefully, no random images now—hate, hate of aliens, of him, who was part of this.

Himself. A city’s dark streets, a deserted way, night, fire leaping up against the horizon, strange hulking shapes looming above the crumbling buildings—a game of hunter and hunted, himself the quarry, and those same dread shapes loping ungainly behind him.

Ambush—unconsciousness—death?—smothered and torn by a press of bodies, alien smells, the cutting discomfort of wire mesh under his naked body, echoing crashes of machinery in great vastness, cold and glaring light. Others like himself, humans, frightened, silent for days and nights of cold and misery and sinister amaut moving saucer-eyed beyond the perimeter of the lights—cold and hunger, until in increasing numbers the others ended as stiff corpses on the mesh.

More crashes of machinery, panic, spurts of memory interspersed with nightmare and strangely tranquil dreams of childhood: drugs and pain, now gabbling faces thrust close to his, shaggy, different humans incapable of speech as he knew it, overwhelming stench, dirty-nailed fingers tearing at him.

Aiela jerked back from the contact and bowed his head into his hands, nauseated; but worse seeped in after: cages, transfer to another ship, being herded into yet filthier confinement, the horror of seeing fellow beings reduced to mouthing animals, constant fear and frequent abuse—himself the victim almost always, because he was different, because he could not speak, because he did not react as they did—the cunning humor of the savages, who would wait until he slept and then spring on him, who would goad him into a rage and then press him into a corner of that cage, tormenting him for their amusement until his screams brought the attendants running to break it up.

At last, strangers, kallia; his transfer, drugged, to yet another wakening and another prison. Aiela saw himself and Chimele as alien and shadowy beings invading the cell: Daniel’s distorted memory did not even recognize him until he met the answering memory in Aiela’s mind.

Enemy. Enemy. Interrogator.Part of him, enemy. The terror boiled into the poor human’s brain and created panic, violence echoing and re-echoing in their joined mind, division that went suicidal, multiplying by the second.

Aiela broke contact, sick and trembling with reaction. Daniel was similarly affected, and for a moment neither of them moved.

No matter, no matter,came into Daniel’s mind, remembrance of kindness, reception of Aiela’s pity for him. Any conditions, anything.He realized that Aiela was receiving that thought, and hurt pride screened it in. “I am sorry,” he concentrated the words. “I don’t hate you. Aiela, help me. I want to go home.”

“From what I have seen, Daniel, I much fear there is no home for you to return to.”

Am I alone? Am I the only human here?

The thought terrified Daniel; and yet it promised no more of the human cages; held out other images, himself alone forever, victim to strangers—amaut, kallia, aliens muddled together in his mind.

“You are safe,” Aiela assured him; and was immediately conscious it was a forgetful lie. In that instant memory escaped its confinement.

They. They—Daniel snatched a thought and an image of the iduve, darkly beautiful, ancient and evil, and all the fear that was bound up in kalliran legend. He associated it with the shadowy figure he had seen in the cell, doubly panicked as Aiela tried to screen. No! What have you agreed to do for them? Aiela!

“No.” Aiela fought against the currents of tenor. “No. Quiet. I’m going to have you sedated– No!Stop that!—so that your mind can rest. I’m tired. So are you. You will be safe, and I’ll come back later when you’ve rested.”

You’re going to report to them—and to lie there—The human remembered other wakings, strangers’ hands on him, his fellow humans’ cruel humor. Nausea hit his stomach, fear so deep there was no reasoning. There were amaut on the ship: he dreaded them touching him while he was unconscious.

“You will be moved,” Aiela persisted. “You’ll wake in a comfortable place next to my rooms, and you’ll be free when you wake, completely safe, I promise it. I’ll have the amaut stay completely away from you if that will make you feel any better.”

Daniel listened, wanting to believe, but he could not. Mercifully the attendant on duty was both kalliran and gentle of manner, and soon the human was settled into bed again, sliding down the mental brink of unconsciousness. He still stretched out his thoughts to Aiela, wanting to trust him, fearing he would wake in some more incredible nightmare.

“I will be close by,” Aiela assured him, but he was not sure the human received that, for the contact went dark and numb like Isande’s.

He felt strangely amputated then, utterly on his own and—a thing he would never have credited—wishing for the touch of his asuthe, her familiar, kalliran mind, her capacity to make light of his worst fears. If he were severed from the human this moment and never needed touch that mind again, he knew that he would remember to the end of his days that he had for a few moments beenhuman.

He had harmed himself. He knew it, desperately wished it undone, and feared not even Isande’s experience could help him. She had tried to warn him. In defiance of her advice he had extended himself to the human, reckoning no dangers but the obvious, doing things his own way, with kastientoward a hurt and desolate creature.

He had chosen. He could no more bear harm to Isande than he could prefer pain for himself: iduvish as she was, he knew her to the depth of her stubborn heart, knew the elethiaof her and her loyalty, and she in no wise deserved harm from anyone.

Neither did the human. Someone meant to use him, to wring some use from him, and discard him or destroy him afterward– be rid of him,Isande had said, even she callous toward him—and there was in that alien shell a being that had not deserved either fate.

It is not reasonable to ask me to venture an opinion on something I have never experienced,Chimele had told him at the outset. She did not understand kalliran emotion and she had never felt the chiabres.Of a sudden he feared not even Chimele might have anticipated what she was creating of them, and that she would deal ruthlessly with the result—a kameth whose loyalty was half-human.

He was kallia, kallia!—and of a sudden he felt his hold on that claim becoming tenuous. It was not right, what he had done—even to the human.

Isande,he pleaded, hoping against all knowledge to the contrary for a response from that other, that blessedly kalliran mind. Isande, Isande.

But his senses perceived only darkness from that quarter.

In the next moment he felt a mild pulse from the idoikkhe,the coded flutter that meant paredre.

Chimele was sending for him.

There was the matter of an accounting.

4

Chimele was perturbed. It was evident in her brooding expression and her attitude as she leaned in the corner of her chair; she was not pleased; and she was not alone for this audience: four other iduve were with her, and with that curious sense of déjà vuIsande’s instruction imparted, Aiela knew them. They were Chimele’s nasithi-katasakke,her half-brothers and -sister by common-mating.

The woman Chaikhe was youngest: an Artist, a singer of songs; by kalliran standards Chaikhe was too thin to be beautiful, but she was gentle and thoughtful toward the kamethi. She had also thought of him with interest: Isande had warned him of it; but Chimele had said no, and that ended it. Chaikhe was becoming interested in katasakke,in common-mating, the presumable cause of restlessness; but an iduve with that urge would rapidly lose all interest in m’metanei.

Beside Chaikhe, eyeing him fixedly, sat her full brother Ashakh, a long-faced man, exceedingly tall and thin. Ashakh was renowned for intelligence and coldness to emotion even among iduve. He was Ashanome’s Chief Navigator and master of much of the ship’s actual operation, from its terrible armament to the computers that were the heart of the ship’s machinery and memory. He did not impress one as a man who made mistakes, nor as one to be crossed with impunity. And next to Ashakh, leaning on one arm of the chair, sat Rakhi, the brother that Chimele most regarded. Rakhi was of no great beauty, and for an iduve he was a little plump. Also he had a shameful bent toward kutikkase—a taste for physical comfort too great to be honorable among iduve. But he was devoted to Chimele, and he was extraordinarily kind to the noi kame and even to the seldom-noticed amaut, who adored him as their personal patron. Besides, at the heart of this soft, often-smiling fellow was a heart of greater bravery than most suspected.

The third of the brothers was eldest: Khasif, a giant of a man, strikingly handsome, sullen-eyed—older than Chimele, but under her authority. He was of the order of Scientists, a xenoarchaeologist. He had a keen m’melakhia—an impelling hunger for new experience—and noi kame made themselves scarce when he was about, for he had killed on two occasions. This was the man Isande so feared, although—she had admitted—she did not think he was consciously cruel. Khasif was impatient and energetic in his solutions, a trait much honored among iduve, as long as it was tempered with refinement, with chanokhia.He had the reputation of being a very dangerous man, but in Isande’s memory he had never been a petty one.

“How fares Daniel?” asked Chimele. “Why did you ask sedation so early? Who gave you leave for this?”

“We were tiring,” said Aiela. “You gave me leave to order what I thought best, and we were tired, we—”

“Aiela-kameth,” Chaikhe intervened gently. “Is there progress?”

“Yes.”

“Will complete asuthithekkhebe possible with this being? Can you reach that state with him, that you can be one with him?”

“I don’t—I don’t think it is safe. No. I don’t want that.”

“Is this yours to decide?” Ashakh’s tones were like icewater on the silken voice of Chaikhe. “Kameth—you were instructed.”

He wanted to tell them. The memory of that contact was still vivid in his mind, such that he still shuddered. But there was no patience in Ashakh’s thin-lipped face, neither patience nor mercy nor understanding of weakness. “We are different,” he found himself saying, to fill the silence. Ashakh only stared. “Give me time,” he said again.

“We are on a schedule,” Ashakh said. “This should have been made clear to you.”

“Yes, sir.”

“Specify the points of difference.”

“Ethics, experience. He isn’t hostile, not yet. He mistrusts—he mistrusts me, this place, all things alien.”

“Is it not your burden to reconcile these differences?”

“Sir.” Aiela’s hands sweated and he folded his arms, pressing his palms against his sides. He did not like to look Ashakh in the face, but the iduve stared at him unblinkingly. “Sir, we are able to communicate. But he is not gullible, and I’m running out of answers that will satisfy him. That was why I resorted to the sedative. He’s beginning to ask questions. I had no more easy answers. What am I supposed to tell him?”

“Aiela.” Khasif drew his attention to the left. “What is your personal reaction to the being?”

“I don’t know.” His mouth was dry. He looked into Khasif’s face, that was the substance of Isande’s nightmares, perfect and cold. “I try—I try to avoid offending him—”

“What is the ethical pattern, the social structure? Does he recognize kalliran patterns?”

“Close to kallia. But not the same. I can’t tell you: not the same at all.”

“Be more precise.”

“Am I supposed to have learned something in particular?” Aiela burst out, harried and regretting his tone at once. The idoikkhepulsed painlessly, once, twice: he looked from one to the other of them, not knowing who had done it, knowing it for a warning. “I’m sorry, but I don’t understand. I was primed to study this man, but no one will tell me just what I was looking for. Now you’ve taken Isande away from me too. How am I to know what questions to start with?”

His answer caused a little ruffling among the iduve, and merry Rakhi laughed outright and looked sidelong at Chimele. “ Au,this one has a sting, Chimele.” He looked back at Aiela. “And what have you learned, thus ignorant of your purpose, o m’metane?”

“That the amaut have intruded into human space, which they swore in a treaty with the Halliran Idaithey would never do. This man came from human space. They lost most of his shipment because these humans weren’t acclimated to the kind of abuse they received. Is that what you want to hear? Until you tell me what you mean to do with him, I’m afraid I can’t do much more.”

Chimele had not been amused. She frowned and stirred in her chair, placing her hands on its arms. “Can you, Aiela, prepare this human for our own examination by tomorrow?”

“That’s impossible. No. And what kind of—?”

“By tomorrow evening.”

“If you want something, then make it clear what it is and maybe I can learn it. But he wants answers. He has questions, and I can’t keep putting him off, not without creating you an enemy—or do you care?”

“You will have to—put him off, as you express it.”

“I’m not going to lie to him, even by omission. What are you going to do with him?”

“I prefer that this human not be admitted to our presence with the promise of anything. Do you understand me, Aiela? If you promise this being anything, it will be the burden of your honor to pay for it; make sure your resources are adequate. I will not consider myself or the nasulbound by your ignorant and unauthorized generosity. Go back to your quarters.”

“I will not lie to him for you.”

“Go back to your quarters. You are not noticed.” This time there was no softness at all in her tone, and he knew he dared not dispute with her further. Even Rakhi took the smile from his face and straightened in his chair. Aiela omitted the bow of courtesy, turned on his heel and walked out.

He had ruined matters. When he was stressed his voice rose, and he had let it happen, had lost his case for it. He had felt when he walked in that Chimele was not in a mood for patience; and he realized in hindsight that the nasithihad tried to avert disaster: Rakhi, he thought, Rakhi, who had always been kind to Isande, had wished to stop him.

He returned to the kamethi level in utmost dejection, realized the late hour and considered returning to the lab and requesting to have a sedative for himself. His nerves could bear no more. But he had never liked such things, liked less to deal with Ghiavre, the iduve first Surgeon; and it occurred to him that Daniel might wake prematurely and need him. He decided against it.

He went to his quarters and prepared for bed, settled in with notebook and pen and diverted his thoughts to record-keeping on Daniel, then, upon the sudden cold thought that the iduve might not respect the sanctity of his belongings, he tore up everything and threw it into the disposal. The suspicion distressed him. As a kallia he had never thought of such things; he had never needed to suspect such ikastienon the part of his superiors.

Daniel had learned such suspicion. It was human.

With that distressing thought he turned out the lights and lay still until his muddled thoughts drifted into sleep.

The idoikkhejolted him, brutally, so that he woke with an outcry and clawed his way up to the nearest chair.

Isande,he had cast, the reflex of two days of dependency; and to his surprised relief there was a response, albeit a muzzy one.

Aiela,she responded, remembered Daniel, instantly tried to learn his health and began to pick up the immediate present: Chimele, summoning him, angry; and Daniel– What have you done?she sent back, shivering with fear; but he prodded her toward the moment, thrusting through the gutter of her drug-hazed thoughts.

“This is Chimele’s sleep cycle too,” he sent. “Does she always exercise her tempers in the middle of the night?”

The idoikkhestung him again, momentarily disrupting their communication. Aiela reached for his clothes and pulled them on, while Isande’s thoughts threaded back into his mind. She scanned enough to blame him for matters, and she was distressed enough to let it seep through; but she had the grace to keep that feeling down. Now was important. He was important. He had to take her advice now; he could be hurt, badly.

“Chimele’s hours are seldom predictable,” she informed him, her outermost thoughts calm and ordered. But what lay under it was a peculiar physical fear that unstrung his nerves.

He looked at the time: it was well past midnight, and Chimele, like Ashakh, did not impress him as one who took the leisure for whimsy. He pulled his sweater over his head, started for the door, but he paused to hurl at Isande the demand that she drop her screening, guide him. He felt her reticence; when it melted, he almost wished otherwise.

Fear came, nightmares of Khasif, chilling and sexual at once. Few things could cause an iduve to act irrationally, but there was one outstanding exception, and iduve when irritated with kamethi were prone to it.

He stopped square in the doorway, blood leaving his face and returning in a hot rush. Her urgency prodded him into motion again, her anger and her terror like ice in his belly. No,he insisted again and again. Isande had been terrified once and long ago: she was scarred by the experience and dwelled on it excessively—it embarrassed him, that he had to express that thought: he knew it for truth. He wished her still.

“It happens,” Isande insisted, with such firmness that it shook his conviction. “It is katasukke—pleasure-mating.” And quickly, without preface, apology, or overmuch delicacy, she fed across what she knew or guessed of the iduve’s intimate habits—alienness only remotely communicated in katasukkewith noi kame, a union between iduve in katasakkethat was fraught with violence and shielded in ritual and secrecy. Katasukkewas gentler: sensible noi kame were treated with casual indulgence or casual negligence according to the mood of the iduve in question; but cruelty was e-chanokhia,highly improper, whatever unknown and violent things they did among themselves. But both katasakkeand katasukketriggered dangerous emotions in the ordinarily dispassionate iduve. Vaikkawas somehow involved in mating, and it was not uncommon that someone was killed. In Isande’s mind any irrationality in the iduve emanated from that one urge: it was the one thing that could undo their common sense, and when it was undone, it was a madness as alien as their normal calm.

He shook off these things, hurried through the corridors while Isande’s anxious presence thrust into his mind behaviors and apologies, fawning kameth graces meant to appease Chimele. Vaikkawith a nas kame had this for an expected result, and if he provoked her further now he would be lucky to escape with his life.

He rejected Isande and her opinions, prideful and offended, and knew that Isande was crying, and frustrated with him and furious. Her anger grew so desperate that he had to screen against her, and bade her leave him alone. He was ashamed enough at this disgraceful situation without having her lodged as resident observer in his mind. He knew her hysterical upon the subject, and even so could not help fearing he was walking into something he did not want to contemplate.

With Isande aware, mind-bound to him.

Leave me alone!he raged at her.

She went; and then he was sorry for the silence.

Chimele was waiting for him, seated in her accustomed chair as a tape unreeled on the wall screen with dizzying rapidity: the day’s reports, quite probably. She cut it off, using a manual control instead of the mental ones of which the iduve were capable—a choice, he had learned, which betokened an iduve with mind already occupied.

“You took an unseemly amount of time responding,” she said.

“I was asleep.” Fear added, shaming him: “I’m sorry.”

“You did not expect, then, to be called?”

“No,” he said; and doubled over as the idoikkhehit him with overwhelming pain. He was surprised into an outcry, but bit it off and straightened, furious.

“Well, consider it settled, then,” she said, “and cheaply so. Be wiser in the future. Return to your quarters.”

“All of you are demented,” he cried, and it struck, this time enough to gray the senses, and the pain quite washed his mind of everything. When it stopped he was on his face on the floor, and to his horror he felt Isande’s hurt presence in him, holding to him, trying to absorb the pain and reason with him to stay down.

“Aiela,” said Chimele, “you clearly fail to understand me.”

“I don’t want—” the idoikkhestung him again, a gentle reproof compared with what had touched him a moment before. It jolted raw nerves and made him cringe physically in dread: the cowardice it instilled made him both ashamed and angry; and there was Isande’s anxious intrusion again. The two-sided assault was too much. He clutched his head and begged his asuthe to leave him, even while he stumbled to his feet, unwilling to be treated so.

She can destroy you,Isande sent him hysterically. She has her honor to think of.Vaikka, Aiela,vaikka!

“Is it Isande?” asked Chimele. “Is it she that troubles you?”

“She’s being hurt. She won’t go away. Please stop it.”

And then he knew that Isande’s idoikkhehad pained her, once, twice, with increasing severity, and the mournful and loyal presence fled.

“Aiela,” said Chimele, “all my life I have dealt gently with my kamethi. Why will you persist in provoking me? Is it ignorance or is it design?”

“It’s my nature,” he said, which further offended her; but this time she only scowled and regarded him with deep dissatisfaction.

“Your ignorance of us has not been noticed: the nearest equivalent is ‘forgiven.’ It will be a serious error on your part to assume this will continue without limit.”

“I honestly,” he insisted, “do not understand you.”

“We are not in the habit of patience with metane-tekasuphre.Nor do we make evident our discomforts. Au, m’metane,I should have the hide from you.” There was self-control; and under it there was a rage that made his skin cold: run now, he thought, and become like the others—no. She would deal with him, explaining matters; he would stand there until she did so.

For a long moment he stood still, expected the touch of the idoikkhefor it; she did not move either.

“Aiela,” she said then, in a greatly controlled voice, “I was disadvantaged before my nasithi-katasakke.” And when he only stared at her, helplessly unenlightened: “For three thousand years Ashanomehas taken no outsider– m’metaneaboard,” she said. “I have never dealt with the likes of you.”

“What am I supposed to say?”

“You disputed with my nasithi.Then you turned the same discourtesy on me. Had you no perception?”

“I had cause,” he declared in temper too deep-running to reckon of her anger, and his hand went to the idoikkheon reflex. “ Thisdoesn’t turn off my mind or my conscience, and I still want to know what you intend with the man Daniel.”

Chimele literally trembled with rage. He had never seen so dangerous a look on any sane and sentient face, but the pain he expected did not come. She stilled her anger with an evident effort.

“ Nas-suphres,” she said in a tone of cosmic contempt. “You are hopeless, m’metane.”

“How so?” he responded. “How so– ignorant?”

“Because you provoke me and trust my forbearance. This is the act of a stupid or an ignorant being. And did I truly believe you capable of vaikka,you would find yourself woefully out-matched. You are not irreplaceable, m’metane,and you are perilously close to extinction at this moment.”

“I have no confidence at all in your forbearance, and I well know you mean your threats.”

“The clumsiness of your language makes rational conversation impossible. You are nothing, and I could wipe you out with a thought. I should think the reputedly ordered processes of the kalliran mind would dictate caution. I fail to perceive why you attack me.”

Mad, he thought in panic, remembering at the same time that she had mental control of the idoikkhe.He wanted to leave. He could not think how. “I have not attacked you,” he said in a quiet, reasoning voice, as one would talk to the insane. “I know better.”

She arose and moved away from him in great vexation, then looked back with some semblance of control restored. “I warned you once, Aiela, do not play at vaikkawith us. You are incredibly ignorant, but you have a courage which I respect above all metane-traits. Do you not understand I must maintain sorithias—that I have the dignity of my office to consider?”

“I’m afraid I don’t understand.”

“ Au,this is impossible. Perhaps Isande can make it clear.”

“ No!No, let her alone. I want none of her explanations. I have my mind clear enough without need of her rationalizations.”

“You are incredible,” Chimele exclaimed indignantly, and returned to him, seized both his hands, and made him sit down opposite her, a contact he hated, and she seemed to realize it. “Aiela. Do not press me. I mustretaliate. We delight to be generous to our kamethi, but we will not have gifts demanded of us. We will not be pressed and not retaliate, we will not be affronted and do nothing. It is physically impossible. Can you not comprehend that?”

Her hands trembled. He felt it and remembered Isande’s warning of iduve violence, the irrational and uncontrollable rages of which these cold beings were capable. But Chimele seemed yet in control, and her amethyst eyes locked with his in deep earnest, so plain a look it was almost like the touch of his asuthi. She let him go.

“I cannot protect you, poor m’metane,if you will persist in playing games of anger with us, if you persist in incurring punishment and fighting back when you receive the consequences of your impudence. You do not want to live under our law; you are not capable of it. And if you were wise, you would have left when I told you to go.”

“I do not understand,” he said. “I simply do not understand.”

“Aiela—” Her indigo face showed stress. His hand still rested across his knee as he leaned forward, too tense to move. Now she took it back into hers, her slim fingers moving lightly across the back of it as if she found its color or the texture of his skin something remarkably fascinating. Pride and anger notwithstanding, he sensed nothing insulting in that touch, rather that Chimele drew a certain calm from that contact, that her mood shifted back to reason, and that it would be a perilous move if he jerked his hand away. He sweated with fear, not of iduve science or power—his rational faculty feared that; but something else worked in him, something subconscious that recognized Chimele and shuddered instinctively. He wished himself out that door with many doors between them; but her hand still moved over his, and her violet eyes stared into him.

“If you had been born among the kamethi,” said Chimele softly, “you would never have run afoul of me, for no nas kame would ever have provoked me so far. He would have had the sense to run away and wait until I had called him again. You are different, and I have allowed for that—this far. And so that you will understand, ignorant kameth: you were impertinent with others and impertinent exceedingly with me—and being Orithain, I dispense judgments to the nasithi.How then shall I descend to publicly chastise a nas kame? They wished to persuade me to be patient; and I chose to be patient, remembering what you are; but then, au,after trading words with my nasithi,you must ignore my direct order and debate me what disposition I am to make of this human.” She drew breath: when she went on it was in a calmer voice. “Rakhi could not reprimand my kameth in my presence; I could not do so in theirs. And there you stood, gambling with five of us in the mistaken confidence that your life was too valuable for me to waste. Were you iduve, I should say that were an extremely hazardous form of vaikka.Were you iduve, you would have lost that game. But because you are m’metane,you were allowed to do what an iduve would have died for doing.”