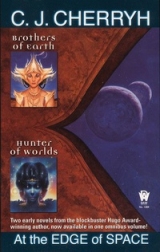

Текст книги "At the Edge of Space (Brothers of Worlds; Hunter of Worlds)"

Автор книги: C. J. Cherryh

Жанр:

Космическая фантастика

сообщить о нарушении

Текущая страница: 20 (всего у книги 36 страниц)

“Come,” said the nas kame, accepting the sheaf of documents and the case under his arm. But he looked down in some surprise as the amaut agent suddenly pushed forward, proffering a letter in his trembling hand.

“His too, lord, his too,” said the amaut.

The nas kame took the letter and put it among the documents; and Aiela looked toward the amaut reproachfully, but the amaut bowed his head and stood rocking back and forth, refusing to look up at him.

Aiela turned his face instead toward the nas kame, appalled that there was no shame there—eyes as kalliran as his that held no recognition of him and cared nothing for his misery.

The nas kame brought him to the moving ramp and preceded him up, looking back once casually at the scene below, ignoring Aiela. Then the belt set them both into the ship’s hold.

Aiela’s eyes were drawn up by the sheer echoing immensity of the place. This hold, as was usual with supply holds, was filled with frames and canisters of goods, row on row, dated, stamped to be listed in the computer’s memory. But it could have contained an entire ship the size of the one Aiela had lately commanded—without the frames and the clutter. No doubt there were other holds that did hold such things as transfer ships and shuttles available at need. It staggered the mind.

The nas kame took his case from him and handed it to an amaut, who waddled ahead of them to a counter and had it stamped and listed and thrust up a conveyor to disappear. Aiela looked after it with a sinking heart, for among his folded clothing he had put his service pistol—nonlethal, like all he weapons of the kalliran service. He had debated it; he had done it, terrified in the act and terrified to go defenseless, without it. But there were no defenses. Standing where he was now, with all Kartos so small and fragile a place beneath them, he realized it for a selfish and cowardly thing to do.

“There was a weapon in that,” he said to the nas kame.

The nas kame took notice of him directly for the fast time, regarding him with mild surprise. He had just put the documents and the tape case on the counter to be similarly stamped and sent up the conveyor. Then he shrugged. “Security will deal with it,” he said, and took Aiela’s arm and held his hand on the counter, compelling him to accept a stamp on the back of his hand, like the other baggage.

Aiela received it with so deep a confusion that he failed to protest; but afterward, with the nas kame holding his arm and guiding him rapidly through the echoing hold, a wave of such shame and outrage came over him that he was almost shaking. He should have said something; he should have done something. He worked his fingers, staring at the purple symbols that rippled across the bones of his hand, and was only gathering the words to object to the indignity when the nas kame roughly turned him and thrust him toward a personnel lift. He went, turned once inside, and expected the nas kame to step in too; but the door slid shut and he was hurtled elsewhere on his own. The controls resisted his attempt to regain the loading deck.

In an instant the lift came to a cushioned halt and opened on a cargo area adapted to the reception of live goods; there were a score or more individual cells and animal pens, some with bare flooring and some padded on all surfaces. Gray-smocked noi kame and amaut in green were waiting for him, took charge of him as he stepped out. One noted the number from his hand onto a slate, then gestured him to move.

As he walked the aisle of compartments he saw one lighted, its facing wall transparent; and his flesh crawled at the sight of the naked pink-brown tangle of limbs that crouched at the rear of it. It looked moribund, whatever it had been—the Orithain ranged far: perhaps it was only one of the forgotten humans of the Esliph; perhaps it was some more dangerous and exotic specimen from the other end of the galaxy, where no metrosiship had ever gone. He delayed, looked more closely; a nas kame pushed him between the shoulders and moved him on, and by now he was completely overwhelmed, dazed and beyond any understanding of what to do. He walked. No one spoke to him. He might have been a nonsentient they were handling.

Physicians took him—at least so he reckoned them—kallia and amaut, who ordered him to strip, and examined him until he was exhausted by their thoroughness, the cold, and the endless waiting. He was beyond shame. When at last they thrust his wadded clothing at him and put him into one of the padded cells to wait, he stood there blankly for some few moments before the cold finally urged him to dress.

He shivered convulsively afterward, walking to lean against one and another of the walls. Finally he knelt down on the floor to rest, limbs tucked up for warmth, his muscles still racked with shivers. There was no view, only white walls and a blank, padded door—cold, white light. He heard nothing to tell him what passed outside until the gentle shock of uncoupling threw him off-balance: they were moving, Kartos would be dropping astern at ever-increasing speed.

It was irrevocable.

He was dead, so far as his own species was concerned, so far as anything he had known was concerned. There were no more familiar reference points.

He was only beginning to come to grips with that, when the room vanished.

He was suddenly kneeling on a carpeted floor that still felt strangely like the padded plastics of the cell. The lights were dim, the walls expanded into an immense dark chamber of carven screens and panels of alien design. A woman in black and diaphanous violet stood before him, a woman of the Orithain, of the indigo-skinned iduve race. Her hair was black: it hung like fine silk, thick and even at the level of her shapely jaw. Her brows were dark, her eyes amethyst-hued, without whites, and rimmed with dark along the edge of the lid. Her nose was arched but delicate, her mouth sensuous, frosted with lavender, the whole of her face framed with the absolute darkness of her hair. The draperies hinted at a slim and female body; her complexion, though dusky from the kalliran view, had a lustrous sheen, as though dust of violet glistened there, as if she walked in another light than ordinary mortals, a universe where suns were violet and skies were of shadowy hue.

He rose and, because it was elethia,he gave her a proper bow for meeting despite their races: she was female, though she was an enemy. She smiled and gave a nod of her graceful head.

“Be welcome, m’metane,” she said.

“Who was it who had me brought here?” he demanded, anger springing out of his voice to cover his fear. “And why did you ask for me?”

“ Vaikka,” she said, and when he did not understand, she shrugged and seemed amused. “ Au, m’metane,you are ignorant and anoikhte,two conditions impossible to maintain aboard Ashanome.We carry no passengers. You will be in my service.”

“No.” The answer burst out of him before he even reckoned the consequences, but she shrugged again and smiled.

“We might return to Kartos,” she said. “You might be set off there to advise them of your objections.”

“And what then?”

“I would prefer otherwise.”

He drew a long breath, let it go again. “I see. So why do you come offering me choices? Noi kame can’t make any, can they?”

“I have scanned your records. I find your decision expected. And as for your assumption of noi kame—no: kamethi have considerable initiative; they would be useless otherwise.”

“Would you have destroyed Kartos?”

His angry question seemed for the first time to perplex the Orithain, whose gentle manner persisted. “When we threaten, m’metane,we do so because of another’s weakness, never of our own. It was highly likely that you would choose to come: elethiaforbids you should refuse. If you would not, surely fear would compel them to bring you. Likewise it is certain that I would have destroyed Kartos had it refused. Any other basis for making the statement would have been highly unreasonable.”

“Was it you?” he asked. “Why did you choose me?”

“ Vaikka—a matter of honor. You are of birth such that your loss will be noticed among kallia: that has a certain incidental value. And I have use for such as you: world-born, but experienced of outer worlds.”

He hated her, hated her quiet voice and her evident delight in his misery. “Well,” he said, “you’ll regret that particular choice.”

Her amethyst eyes darkened perceptibly. There was no longer a smile on her face. “ Kutikkase-metane,” she said. “At the moment you are no more than sentient raw material, and it is useless to attempt rational conversation with you.”

And with blinding swiftness the white light of the cell was about him again, yielding white plastic on all sides, narrow walls, white glare. He flinched and covered his eyes, and fell to his knees again in the loneliness of that cubicle.

Then, not for the first time in the recent hour, he thought of self-destruction; but he had no convenient means, and he had still to fear her retaliation against Kartos. He slowly realized how ridiculous he had made himself with his threat against her, and was ashamed. His entire species was powerless against the likes of her, powerless because, like Kartos, like him, they would always find the alternative unthinkably costly.

He came docilely enough when they brought him out into the laboratory, expecting that they would simply lock about his wrist the idoikkhe,such as they themselves wore—that ornate platinum band that observers long ago theorized provided the Orithain their means of control over the noi kame.

Such was not the case. They had him dress in a white wrap about his waist and lie down again on the table, after which they forcibly administered a drug that made his senses swim, dispersing his panic to a vague, all-encompassing uneasiness.

He realized by now that becoming nas kame involved more than accepting that piece of jewelry—that he was going under and that he would not wake the same man. In his drugged despair he begged, he invoked deity, he pleaded with them as fellow kallia to consider what they were doing to him.

But they ignored his raving and with an economy of effort, slipped him to a movable table and put him under restraint. From that point his perceptions underwent a rapid deterioration. He was conscious, but he could not tell what he was seeing or hearing, and eventually passed over the brink.

2

The dazed state gave way to consciousness in the same tentative manner. Aiela was aware of the limits of his own body, of a pain localized in the roof of his mouth and behind his eyes. There was a bitter chemical taste and his brow itched. He could not raise his hand to scratch it. The itch spread to his nose and was utter misery. When he grimaced to relieve it, the effort hurt his head.

He slept again, and wakened a second time enough to try to move, remembering the bracelet that ought to be locked about his wrist. There was none. He lifted his hand—free now—and saw the numbers still stamped there, but faded. His head hurt. He touched his temple and felt a thin rough seam. There was the salt of blood in his mouth toward the back of his palate; his throat was raw. He felt along the length of the incision at his temple and panic began to spread through him like ice.

He hated them. He could still hate; but the concentration it took was tiring—even fear was tiring. He wept, great tears rolling from his eyes, and even then he was fading. Drugs, he thought dimly. He shut his eyes.

A raw soreness persisted, not of the body, but of the mind, a perception, a part of him that could not sleep, like an inner eye that had no power to blink. It burned like a white light at the edge of his awareness, an unfocused field of vision where shadows and colors moved undefined. Then he knew what they had done to him, although he did not know the name of it.

“ No!” he screamed, and screamed again and again until his voice was gone. No one came. His senses slipped from him again.

At the third waking he was stronger, breathing normally, and aware of his surroundings. The sore spot was there; when he worried at it the place grew wider and brighter, but when he forced himself to move and think of other things, the color of the wall, anything at all, it ebbed down to a memory, an imagination of presence. He could control it. Whatever had been done to his brain, he remembered, he knew himself. He tested the place nervously, like probing a sore tooth; it reacted predictably, grew and diminished. It had depth, a void that drew at his senses. He pulled his mind from it, crawled from bed and leaned against a chair, fighting to clear his senses.

The room had the look of a comfortable hotel suite, all in blue tones, the lighted white doorway of a tiled bath at the rear—luxury indeed for a starship. His disreputable serviceman’s case rested on the bureau. A bench near the bed had clothing—beige—laid out across it.

His first move was for the case. He leaned on the bureau and opened it. Everything was there but the gun. In its place was a small card: We regret we cannot permit personal arms without special clearance. It is in storage. For convenience in claiming your property at some later date, please retain this card, 509-3899-345.

He read it several times, numb to what he felt must be a certain grim humor. He wiped at his blurring vision with his fingers and leaned there, absently beginning to unpack, one-handed at first, then with both. His beloved pictures went there, so, facing the chair which he thought he would prefer. He put things in the drawer, arranged clothing, going through motions familiar to a hundred unfamiliar places, years of small outstations, hardrock worlds—occupying his mind and keeping it from horrid reality. He was alive. He could remember. He could resent his situation. And this place, this room, was known, already measured, momentarily safe: it was his,so long as he opened no doors.

When he felt steady on his feet he bathed, dressed in the clothes provided him, paused at the mirror in the bath to look a second time at his reflection, when earlier he had not been able to face it. His silver hair was cropped short; his own face shocked him, marred with the finger-length scar at his temple, but the incision was sealed with plasm and would go away in a few days, traceless. He touched it, wondered, ripped his thoughts back in terror; light flashed in his mind, pain. He stumbled, and came to himself with his face pressed to the cold glass of the mirror and his hands spread on its surface to hold him up.

“Attention please.” The silken voice of the intercom startled him, “Attention. Aiela Lyailleue, you are wanted in the paredre.Kindly wait for one of the staff to guide you.”

He remembered an intercom screen in the main room, and he pushed himself square on his feet and went to it, pressed what he judged was the call button, several times, in increasing anger. A glowing dot raced from one side of the screen to the other, but there was no response.

He struck the plate to open the door, not expecting that to work for him either, but it did; and instead of an ordinary corridor, he faced a concourse as wide as a station dock.

At the far side, stars spun past a wide viewport in the stately procession of the saucer’s rotation. Kallia in beige and other colors came and went here, and but for the luxury of that incredible viewport and the alien design of the shining metal pillars that spread ornate flanged arches across the entire overhead, it might have been an immaculately modern port on Aus Qao. Amaut technicians waddled along at their rolling pace, looking prosperous and happy; a young kalliran couple walked hand in hand; children played. A man of the iduve crossed the concourse, eliciting not a ripple of notice among the noi kame—a tall slim man in black, he demanded and received no special homage. Only one amaut struggling along under the weight of several massive coils of hose brought up short and ducked his head apologetically rather than contest right of way.

At the other end of the concourse an abstract artwork of metal over metal, the pieces of which were many times the size of a man, closed off the columned expanse in high walls. At their inner base and on an upper level, corridors led off into distance so great that the inner curvature of the ship played visual havoc with the senses, door after door of what Aiela judged to be other apartments stretching away into brightly lit sameness.

The iduve was coming toward him.

Panic constricted his heart. He looked to one side and the other, finding no other cause for the iduve’s interest. And then a resolution wholly reckless settled into him. He turned and began at first simply to walk away; but when he looked back, panic won: he gathered his strength and started to run.

Noi kame stared, shocked at the disorder. He shouldered past and broke into a corridor, not knowing where it led—the ship, vast beyond belief, tempted him to believe he could lose himself, find its inward parts, at least understand the sense of things before they found him again and forced their purposes upon him.

Then the section doors sealed, at either end of the hall.

Noi kame stared at him, dismayed.

“Stand still,” one said to him.

Aiela glanced that way: hands took his arms and he twisted out and ran, but they closed and held him. The first man rash enough to come at him from the front flew backward under the impact of his thin-soled boot; but he could not free himself. An amaut took his arms, a grip he could not break, struggle as he would; and then the doors parted and the iduve arrived with a companion, frowning and businesslike. When Aiela attempted to kick at them, that iduve’s backhand exploded across his face with force enough to black him out: a hypospray against his arm finished his resistance.

He was not entirely unconscious. He tried to walk because the grip on his arms hurt less when he carried his own weight, but it was some little distance before he even cared where they were taking him. For a dizzying moment they rode a lift, and stepped off into another corridor, and then came into a hall. On the left a screen of translucent blue stone carved in scenes of reeds and birds separated a vast dim hall from this narrower chamber.

Then he remembered this place, this hall like a museum, with its beautiful fretted panels and lacquered ceiling, its cases for display, its ornate and alien furnishings. He had stood here once before from the vantage point of his cell, but this was reality. The carpets he walked gave under his boots, and the woman that awaited them was not projection, but flesh and blood.

“Aiela,” she said in her accented voice, “Aiela Lyailleue: I am Chimele, Orithain of Ashanome.And such action is hardly an auspicious introduction, nor at all wise. Takkh-ar-rhei, nasithi.”

Aiela found himself free—dizzied, bruised, thoroughly dispossessed of the recklessness to chance another chastisement at their hands. He moved a step—the iduve behind him moved him back precisely where he had stood.

She spoke to her people, frowning: they answered. Aiela waited, with such a physical terror mounting in him as he had never felt in any circumstances. He could not even shape it in his thoughts. He felt disconnected, smothered, wished at once to run and feared the least movement.

And now Chimele turned from him and returned with the wide band of an idoikkheopen in her indigo fingers—a band of three fingers’ width, with a patchwork of many colors of metal on its inner surface, a thread of black weaving through it all. She held it out for him, expecting him to offer his wrist for it, and now, now was the time if ever he would refuse anything again. He could not breathe, and he felt strongly the threat of violence at his back; his battered nerves refused to carry the right impulses. He saw himself raise an arm that seemed part of another body, heard a sharp click as the cold band locked, felt a weight that was more than he had expected as she took her hands away.

A jewel of milk and fire shone on its face. The asymmetry of iduve artistry flashed in metal worth a man’s life in the darker places of the Esliph. He stared at it, realizing beyond doubt that he had accepted its limits, that no foreign thing in his skull had compelled the lifting of his arm; there was a weakness in Aiela Lyailleue that he had never found before, a shameful, unmanning terror.

It was as if something essential in him had torn away, left behind in Kartos. He feared. For the first time he knew himself less than other beings. Without dignity he tore at the band, but of the closure no trace remained save a faint diffraction of light—no clasp and no yielding.

“No,” she said, “you cannot remove it.”

And with a gesture she dismissed the others, so that they stood alone in the hall. He was tempted then to murder, the first time he had ever felt a hate so ikas—and then he knew that it was out of fear, female that she was. He gained control of himself with that thought, gathered enough courage to plainly defy her: he spun on his heel to stalk out, to make them use force if they would. That much resolve he still possessed.

The idoikkhestung him, a dart of pain from his fingertips to his ribs. At the next step it hurt; and he paused, measuring the long distance to the door against the pain that lanced in rising pulses up his arm. A greater shock hit him, waves enough to jolt his heart and shorten his breath.

He jerked about and faced her—not to attack: if he had any thought then it was to stand absolutely still, anything, anything to stop it. The pulse vanished as he did what she wanted, and the ache faded slowly.

“Do not fear the idoikkhe,” said Chimele. “We use it primarily for coded communication, and it will not greatly inconvenience you.”

He was shamed; he jerked aside, hurt at once as the idoikkheactivated, faced her and felt it fade again.

“I do not often resort to that,” said Chimele, who had not yet appeared to do anything. “But there is a fine line between humor and impertinence with us which few m’metaneican safely tread. Come, m’metane-toj,use your intelligence.”

She allowed him time, at least: he recovered his composure and caught his breath, rebuilding the courage it took to anger her.

“So what is the law here?” he asked.

“Do not play the game of vaikkawith an iduve.” He tried to outface her with his anger, but Chimele’s whiteless eyes locked on his with an invading directness he did not like. “You are bound to find the wager higher than you are willing to pay. You have not been much harmed, and I have extended you an extraordinary courtesy.”

“I don’t think so,” he said, and knew what to expect for it, knew and waited until his nerves were drawn taut. But Chimele broke from his eyes with a shrug, gestured toward a chair.

“Sit and listen, kameth. Sit and listen. I do not notice your attitude. You are only ignorant. We are using valuable time.”

He hesitated, weighed matters; but the change in her manner was as complete as it was abrupt, almost as if she regretted her anger. He still thought of going for the door; then common sense reasserted itself, and he settled on the chair opposite the one she chose.

Pain hit him, excruciating, lancing through his eyes and the back of his skull at once. He bent over, holding his face, unable to breathe. That sensation passed quickly, leaving a throbbing ache behind his eyes.

“Be quiet,” she said. “Anger is the worst possible response.”

And she brought him a tiny glass of clear liquid. He drank, too shaken to argue, set the empty crystal vessel on the table. He missed the edge with his distorted vision: it toppled off and she imperturbably picked it up off the costly rug and set it securely on the table.

“I am not responsible,” she said when he looked hate at her.

There was something at the edge of his mind, the void now full of something dark that reached up at him, and he fought to shut it out, losing the battle as long as he panicked. Then it ceased, firmly, outside his will.

“What was done to me?” he cried. “What was it?”

“The chiabres,the implant: I would surmise, though I do not do so from experience, that you reacted on a subconscious level and triggered defenses, contacting what was not prepared to receive you. This chiabresof yours has two contacts, mind-links to your asuthi—your companions. One is probably in the process of waking, and I assure you that fighting an asuthe is not profitable.”

“I had rather be dead,” he said. “I would rather die.”

“ Tekasuphre.Do not try my patience. I called you here precisely to explain matters to you. I have great personal regard for your asuthe. Do I make myself clear?”

“Am I joined to one of you?”

“No,” she said, suddenly laughing—a merry, gentle sound, but her teeth were white and sharp. “Nature provided for us in our own fashion, m’metane.Kallia and even amaut find asuthithekkhepleasant, but we would not.”

And the walls closed about them. Aiela sprang to his feet in alarm, while Chimele arose more gracefully. The light had brightened, and beside them was a bed whereon lay a kalliran woman of great beauty. She stirred in her sleep, silvery head turning on the pillow, one azure hand coming to her breast. There was the faint seam of a new scar at her temple.

“She is Isande,” said Chimele. “Your asuthe.”

“Is it—usual—that different sexes—”

Chimele shrugged. “We have not found it of concern.”

“Was she the one I felt a moment ago?”

“It is not reasonable to ask me to venture an opinion on something I have never experienced. But it seems quite possible.”

He looked from Chimele to the sweet-faced being who lay on the bed, the worst of his fears leaving him at once. He felt even an urge to be sorry for Isande, no less than for himself; he wondered if she had consented to this unhappy situation, and was about to ask Chimele that question.

The walls blinked smaller still, and they stood in a room of padded white, a cell. At their left, leaning against the transparent face of the cell, was that same naked pink-brown creature Aiela remembered lying inert in the corner on his entry into the lab. Now it turned in the rapid dawning of terror: one of the humans of the Esliph, beyond doubt, and as stunned as he had been that day—how long ago?—that Chimele had appeared in his cell. The human stumbled back, hit the wall where there was no wall in his illusion, and pressed himself there because there was no further retreat.

“He is Daniel,” said Chimele. “We think this is a name. That is all we have been able to obtain from him.”

Aiela looked at the hair-matted face in revulsion, heart beating in panic as the human stretched out his hands. The human’s dark eyes stared, white around the edges, but when his hands could not grasp them he collapsed into a knot, arms clenched, sobbing with a very manlike sound.

“This,” said Chimele, “is your other asuthe.”

Aiela had seen it coming. When he looked at Chimele it was without the shock that would have pleased her. He hardened his face against her.

“And you know now,” she continued, unmoved, “how it feels to experience the chiabreswithout understanding what it is. This will be of use to you with him.”

“I thought,” he recalled, “that you had regard for Isande.”

“Precisely. Asuthithekkhebetween species has always failed. I am not willing to risk the honor of Ashanomeby endangering one of my most valued kamethi. You are presently expendable. Surgery will be performed on this being in two days. You had that interval to learn to handle the chiabres.Try to approach the human. Perhaps he will respond to you. Amaut are best able to quiet him, but I do not think he finds pleasure in their company or they in his. Those two species demonstrate a strong mutual aversion.”

Aiela nerved himself to take a step toward the being, and another. He went down on one knee and extended his hand.

The creature gave a shuddering sob and scrambled back from any contact, wild eyes locked on his. Of a sudden it sprang for his throat.

The cell vanished, and Aiela had sprung erect in the safety of the Orithain’s own shadowed hall. He still trembled, in his mind unconvinced that the hands that had reached for his throat were insubstantial.

“You are dismissed,” said Chimele.

The nas kame who escorted him simply abandoned him on the concourse and advised him to ask someone if he lost his way again. There was no mention of any threat, as if they judged a man who wore the idoikkheincapable of any further trouble to anyone.

In effect, he knew, they were right.

He walked away to stand by the immense viewport, watching the stars sweep past, now and again the awesome view of the afterstructure of the ship as the rotation of the saucer carried them under the holding arm, alternate oblivion and rebirth from the dark, rotation after slow rotation, the blaze of Ashanome’srunning lights, the dark beneath, the lights, the star-scattered fabric of infinity, a ceaseless rhythm.

Likely none of the thousands of kallia that came and went on the concourse knew much of Aus Qao. They had been born on the ship, would live their lives, bear their children, and die on the ship. Possibly they were even happy. Children came, their bright faces and shrill voices and the rhymes of the games they played the same as generations before had sung, the same as kalliran children everywhere. They flitted off again, their glad voices trailing away into the echoing immensities of the pillared hall. Aiela kept his face toward the viewport, struggling with the tightness in his throat.

Kartos Station would be about business as usual by now, and its people would have cleansed him from their thoughts and their conscience. Aus Qao would do the same; even his family must pick up the threads of their lives, as they would do if he were dead. His reflection stared back out of starry space, beige-clad, slender, crop-headed—indistinguishable from a thousand others that had been born to serve the ship.

He could not blame Kartos. It was a fact as old as civilization in the metrosi,a deep knowledge of helplessness. It was that which had compelled him to take the idoikkhe.Kallia were above all peaceful, patiently stubborn, and knew better how to outwait an enemy that how to fight.