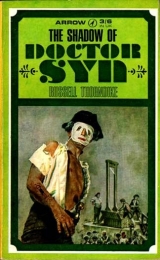

Текст книги "The Shadow of Dr Syn"

Автор книги: Russell Thorndike

Жанр:

Исторические приключения

сообщить о нарушении

Текущая страница: 9 (всего у книги 16 страниц)

The two men laughed heartily at this. Then Jimmie Bone slapped hand to knee and exclaimed: ‘Zounds – talking of finding and losing – no news I said, and here I am with some in my pocket.’ And he drew out the wallet he had taken in Quarry Hill from Captain Foulkes.

‘There’s something here that I think you ought to have,’ he said. ‘You see, I’ve had a good deal of experience with gentlemen’s wallets, and this one sort of puzzled me. “Here,” says I, “is a good one. Hand made. Beautiful stitching. Gold initial and made of Russian leather.” There it was in my hand, empty – although it didn’t feel empty. A nice exciting crackling of paper. “James,” I said, “you may have stumbled on this gentleman’s emergency note,” so I turns it over and has a good look, and there at the top was a different stitching. So, Gentleman James being curious, I ripped out the stitching and inside here was this.” He drew from behind the outer leather a thin folded paper, covered with writing, which he handed over to Doctor Syn.

‘You can read the language – I can’t. But I can read a name, even in French. And that’s why I thought you’d better have it.’

Doctor Syn turned to the name, and gave a long low whistle of astonishment. Then quickly reading the letter through he looked up at the highwayman, and his voice was grave. ‘’Tis good that you have such a sensitive touch, Jimmie. Here’s a stupendous piece of news indeed, though for a time I’ve had an inkling that something was afoot. I’ll deal with it, James. As you have gathered, it is a letter written by none other than Robespierre himself to a Monsieur Barsard. For the present I must urge you to keep even that knowledge to yourself. All I can tell you other than this is that he proposes —‘

Upon that instant the nearby hooting of an owl was heard, and the door opened. Doctor Syn quickly replaced the letter in the wallet, which he put in his pocket, as a figure entered the room. Masked and hooded, it was terrible to behold. One might have expected its voice to be sepulchral. Instead came, surprisingly enough, the plaintive, muffled voice of Mr. Mipps. ‘Oh, me mask. Don’t fit,’ he complained. ‘Give Pedro mine. This didn’t fit him neither, but it’ll give me cruel headache, sure as coffin nails. Owls is on. ’Ear ’em? Ain’t you ready? ’Orses are. Why, blow me down! Ain’t you chose your present yet? Ain’t you been lingy? Better be quiddy.’

Mr. Bone made a rush for the table and quickly sorted out some half a dozen trinkets, and turning, begged Doctor Syn to give him his advice, telling him that he meant to make a personal apology to Miss Gordon with one of them, and which did he think suitable?

With a nod of approval for his gentlemanly thought, Doctor Syn began to make his choice from the articles when Mr. Mipps, who was at the table inspecting some of the others, cried, ‘Knock me up solid – ’ere’s the very thing and you’ve been and gone and missed it!’ He held out for them to see a brooch, a dog’s head carved out of crystal, painted, and set in gold looking remarkably life-like.

‘Why, yes,’ cried Doctor Syn, ‘’tis indeed the very thing. For though it is not a poodle, it is at least a white dog and bears a faint resemblance to Mister Pitt.’

‘Poodle,’ repeated Mipps. ‘Is that what you calls ’em? A old-fangled name for a new-fangled dog. Looks more like one of them clipped yew hedges to me.’

Mr. Bone, admitting he had been dense, besought Doctor Syn to give it to her when convenient, to which Doctor Syn replied he would do so the very first thing in the morning, with her own as well. Then, as Jimmie Bone had already been out once that night and ridden hard, he bade him go to rest, adding that he would be informed of the next run, which probably, he said, would not be for a week.

The warning cries of the owl becme more insistent as Doctor Syn leapt into the dry dyke and through the secret door.

Three minutes later three wild mounted figures dashed from the stable, topped the dyke and galloped seawards, whence came the twinkle of innumerable lights as the ‘flashers’ sent their message round the Marsh.

Thus did Pedro say good-bye to his master upon the beach at Littlestone, where a lugger, divested of its cargo, signalled him to board.

The diminutive Spanish captain, mounted now upon the shoulders of an enormous fisherman waiting to carry him out waist deep to the departing vessel, was almost as tall as the gaunt figure astride Gehenna.

In this curious position the two men clasped hands and the Scarecrow whispered: ‘When you reach the Somme and hand your prisoners over to Duloge, bid him from me to watch for a certain Monsieur Barsard. And now, farewell, my little Pedro.’

Standing at the edge of the sea, horse and man motionless, one dark shadow looking bronze against the merging silver of the sea and sky, Doctor Syn watched the lugger till it was almost out of sight, and wondered if his good friend Duloge would meet with one Barsard.

Chapter 14

Concerning a Late-blooming Rose and an Early Visitor

Doctor Syn sat at his desk in the library, in a silver vase before him one late-blooming rose, its red velvet petals already opening to the heat of the room, though he had picked it but half an hour before in the frosty garden beneath his window. Beside it on the table lay a pair of gauntlet riding-gloves. He looked at them and smiled as he noted that they had taken on the shape of her slim, determined hands. The fingers slightly curved as though still mastering some unruly horse, and at the sight he felt a mighty pull at the reins of his own heart. He raised his head and, looking through the curved panes of the bow window, saw behind the sharp etching of the rookery trees the many spiralled stacks of the Court House chimneys. He smiled again, imagining the bustle inside that house, surely continuing from the night before. He wondered how she’d slept, or whether, like himself, she’d been wakeful to the dawn, and then remembered, somewhat wistfully, that her youthful health would undoubtedly have claimed the sleep which he had wooed in vain.

But in spite of his night’s activities and the fact that he had not slept, he felt alive and exhilarated, deliberately stamping from his mind any dark thoughts that might have lingered there. It was with the suspicion of a sigh, therefore, that he forced himself to return to another urgent matter. Taking from his pocket the wallet which Mr. Bone had given him the night before, he fell to an examination of its contents.

There seemed to be some points in Robespierre’s threatening letter to this Barsard that puzzled him, for he read it carefully two or three times, referring to this line or that, his eyes tightening with concentration, and his intelligent face set into lines of perplexed determination. Then like a barrister preparing his brief he wrote upon a slip of paper the questions he had asked himself during his perusal of the letter, and against each question worked out problematical answers. His writing, scholarly and small as print, easy enough to read in the ordinary course of events, assumed a different form, and his fine pen, which usually travelled rapidly, moved carefully, each letter separate, so that upon finishing a phrase it looked like a row of curious numbers or hieroglyphics. Doctor Syn was in fact writing in ancient Greek.

Having come to a satisfactory conclusion, he replaced the letter in the wallet and, putting it in his pocket, rose and went to a distant bookshelf. Here he selected a calf-bound tome, and, taking it to his desk, opened it at random, made a mental note of the page, placed his Greek notes within, and closed it, carrying the volume to its original place upon the shelf.

He then drew from his pocket a notebook which he used for jotting down parochial items – such as notes on sermons – a text here, a phrase there, so that no one upon opening it would have been surprised to see an extra jotting

– Willet on the Romans, page 123.

He was standing by the fire filling his churchwarden pipe with sweet Virginia tobacco when there came a respectful privilege-to-work-there knock upon the door, and upon his pleasant ‘Come in’, Mrs. Honeyballs’s smiling countenance appeared round the door; her rosy face, still shining from the morning soap, peeped out from underneath a large mob cap, while her ample figure, confined within a quantity of starch, bobbed dutifully, as she asked in her usual lilt: ‘How are you this morning, sir? Hope I’m not intrudin’. Mr. Mipps has told me you breakfast at the Court House. Oh dear. Here am I forgettin’. Left him on the doorstep. Such a swagger gentleman. Standing on the doorstep. Shall I ask him in, sir? Didn’t hear his name, sir. Met you in the coach, sir.’

Doctor Syn did not seem to be surprised at this early visitor, though amused at the manner in which Mrs. Honeyballs announced him. With a kindly smile he said: ‘Thank you, Mrs. Honeyballs. Will you ask Captain Foulkes to step in?’

She bobbed and went out again, unable to suppress her own opinion, which was, ‘What an hour for callin’.’

Drawing briskly at his pipe, the Vicar stood waiting, an inscrutable smile upon his face.

Captain Foulkes entered the library, and, advancing to the fire, bowed and said: ‘I trust, reverend sir, you will forgive my intrusion at this hour, but the weather being fine and the sea air most invigorating, I thought an early rise and a gallop before breakfast would benefit my health and blow away the plaguey cobwebs of London.’

His manner this morning was very different. The arrogance gone, it was almost conciliatory, though his clothes belied the statement of an early rise. Indeed, they did not have the air of a man who had recently completed a fashionable toilet and ridden but a few miles. Instead they bore signs of hard riding, and his eyes, slightly bloodshot, had the look of one who had for hours been staring into darkness. The Doctor, noting this, told himself here was no morning canter for the health. More like an all-night gallop for his purse. He had come to find the Scarecrow and was obviously not wasting any time.

But the Captain continued with his dubious apologies. ‘The tide being low, and the sands hard, I had a good gallop, and on enquiry from a fisherman I found I was at Dymchurch, opposite your house, and bethought me of your invitation.’

‘Why, Captain Foulkes, of course. You’re very welcome. Pray do not excuse yourself, for I too have been up for some considerable time.’ The Captain may have given him a doubtful look, but Doctor Syn did not appear to notice and continued: ‘Ah yes – the coach. You had a most unfortunate experience. Dear me. That highwayman. So barbaric to want to rob a fellow creature of his boots. But take comfort in the thought, sir, perhaps they pinch him. Oh, I see you have procured another pair.’ Indeed the Captain was wearing some very smart though extraordinarily muddy Hessians. ‘Then it cannot be my carpet-slippers you have come to borrow,’ continued the Vicar. ‘Now let me see, what was it you wanted? A weapon. Yes. Yes. He took your sword as well. Well, you shall have the choice of my armoury,’ and pointed towards the only corner of the library that was unoccupied by bookshelves.

Captain Foulkes, following his gesture, was surprised to see the finest collection of Toledo steel that he had ever set eyes on in all his swordsman’s career, and wondered how they came to be in the possession of this country parson. But Syn went on, explaining: ‘As I told you, in my youth I was considered not without promise in the art. I have not always been,’ and here he laughed playfully, ‘the fusty old parson you see before you now, for I must tell you, sir, that in my travels I have preached the Word in many far-flung places – from the Chinese Islands to the Red Indians in the Americas. Charming people – much more civilized than we are. I was no Quaker, sir, and thought it best to have good steel about me. So I made my little collection

– more or less as a hobby, of course. Now take your choice.’

The Captain appeared to be overwhelmed with such generosity, and told the Vicar that although he remembered his kind offer, and would be delighted to avail himself of it, he had in truth only come that morning to pay his respects and offer his apologies, for he knew he had behaved somewhat churlishly in the coach, as indeed he had also done at Crockford’s.

Doctor Syn made light of this, saying that the London air always made him too a trifle testy, for the noise and bustle, to say nothing of the late hours, were apt to fray the nerves, but that now, he hoped, the Captain was feeling more invigorated after his little rest-cure in their humble corner of the world. ‘For,’ he continued, ‘did you not say that you were visiting the coast for your health? No, no, of course, you had another reason. How foolish – my poor old brain. It all comes back to me – your wager. You were coming down to rid us of our Scarecrow. Is that not so, sir? Yes, of course, that’s why you need the weapon. That was the only reason for your visit, was it not?’

The Captain appeared to be relieved at this question, for indeed he had been wondering how to broach the subject, and having selected a sword to his liking (Doctor Syn noting with amusement that he had chosen the finest in his collection), he went on to say that in truth there was something else – that he had come to the Vicar for advice and assistance. Doctor Syn replied that it was a curious coincidence, for but yesterday morning another member of Crockford’s ahd called for the same purpose, and he understood that the young gentleman had been an acquaintance of Captain Foulkes. ‘Now what was his name?’ he said. ‘Dear me, my memory. Oh yes, Lord Cullingford. Quite a charming boy – if a trifle misguided, but I rather think I succeeded in bringing another stray lamb into the fold. It appeared that the poor youth was somewhat in debt, and,’ he continued confidentially, as though they, as older men, knew the ways of the wicked world, ‘I lent him some few hundred guineas from parochial funds. Oh, I have no fear of not getting it back, for he seemed to me the soul of honour, and told me he fully intended quitting his extravagant life to join the Colours. I had succeeded, you see, in persuading him that to try to catch this rascally Scarecrow single-handed was in my mind only asking for trouble, since the Army, the Navy, and the Revenue alike have never succeeded in catching him, and that the chance he had of winning the two thousand guineas reward was remote indeed. He then admitted that in the Captain’s case it was a different matter, as of course he had heard that Captain Foulkes was such a brilliant swordsman, if indeed he was lucky enough to meet the Scarecrow, and he wondered, having also heard of the Captain’s offer to meet the Scarecrow in open duel, whether his challenge could be accepted, adding wistfully that there was a fight he would like to see.’

Foulkes was not a little annoyed when he heard that Lord Cullingford had stolen this march upon him, and then had turned ‘so mighty pious’, and he vowed that he would attend to the young puppy at his convenience, though at the moment his own affairs were too pressing to worry further upon the subject, and the Vicar had somewhat mollified him by his flattery. So he admitted that though he had come to Doctor Syn for advice about the Scarecrow, that also was not the only reason. Then, flattering in his turn, he said that he had heard Doctor Syn was such a good man that even the miscreants of his parish were not afraid to approach him for guidance, and that in truth they even paid him their tithes. So he wondered if it would be possible for him to convey a message to that confounded highwayman who had put him to such inconvenience. ‘For,’ he went on, ‘not only did he take my sword and boots, but he deprived me of something on which I set great sentimental value, in short, my wallet, given to me by a dear friend. If he would return it I am willing to pay a large reward, as well as allowing him to keep such money as he found inside it, without complaint to the Authorities or personally seeking redress.’

To this the Vicar replied that it was a very grave matter and he could not promise Captain Foulkes an assured satisfaction, for he never knew when these naughty rogues were going to ‘bob up next’, though as a rule they were punctilious in paying their tithes. Then, looking somewhat apologetic, he said: ‘I fear I very stupidly refused to take my tithes from Mr. Bone due for his latest misdemeanour, because of his gentlemanly gesture in returning to me all the valuables which you saw him take from Miss Agatha Gordon. He told me himself that he had never been privileged to rob such an aristocratic, charming old Scots lassie, and asked me to give them back with his apology. Why, he even sent her a little personal gift, in lieu of her forgiveness. Quaint fellow,’ he chuckled, ‘romantically inclined, though I suspect ’tis the first time Gentleman James has played the gallant to a lady of her years. But there, I fear all this must be very annoying for you, having lost something of such great sentimental value. Your dear friend – passed on, no doubt?’ Then seeing that the Captain’s expression was blank, went on: ‘No? Oh, and a wallet too. Most irritating. All one’s private papers. So intimate. I feel for you most strongly and will certainly do my best.’

Once again the Captain had that curious feeling that he was being laughed at, and felt the same qualms of doubt concerning the Vicar’s sincerity. But stifling these feelings as he still hoped to make use of the Vicar, he thanked him and, summoning up an uneasy laugh, he suggested: ‘I merely thought, sir, that if this highwayman is so prompt to pay his tithes, the same thing may apply to this Scarecrow, and were you to be so – “fortunate”, shall we say?

– as to meet him, I would be exceedingly grateful if you would convey a message to him too.’

Doctor Syn once again became the Shepherd of his Flock, as without the hint of a double meaning he assured his visitor that, though he would not betray the confidences of a black sheep any more than he would of a white, at least he would do his best. ‘You see, sir,’ he went on, ‘I do not feel so uneasy about you as I did about poor young Cullingford, so if I am successful in arranging this meeting, perhaps you will do me the honour of allowing me to be your “second”.’

The Captain looked a little surprised at this last remark, but before he had time to reply the Vicar continued. ‘It is none of my business, I know,’ he said with deference, ‘but I must say I am a little perplexed, for apart from what I am sure will be an exhilarating fight, I am at a loss to know your motive in calling him out, for a gentleman of your means can surely not be in need of such a paltry sum. A personal matter, no doubt? Some slur upon your character? I quite understand. Pray forgive me for my impertinence.’

The Vicar appeared to be so understanding and so genuinely concerned about the matter that Foulkes, all suspicions swept away, was encouraged to go still further, and told the Vicar, very confidentially, that his challenge to the Scarecrow was in reality a blind; that he had no wish to kill him but to meet him, as he was entrusted with a very special proposition from a certain gentleman called Barsard. Adding that he felt sure the Scarecrow would not refuse his offer as it would be very lucrative, and came from a man who had unlimited power. ‘Indeed,’ the Captain now seemed to be playing his trump card, ‘he will not dare refuse when he learns from me certain information gleaned from the distant Caribbean Seas.’

If these words meant anything to Doctor Syn, he did not show it. Indeed he appeared not to understand, and his bewildered expression drew the Captain still further, as with a condescending smile he said: ‘I see my meaning has escaped you, sir, for your way of living and your holy mission during your travels would not have brought you into contact with the uncivilized tyrants of the Caribbean Sea, and one in particular, Clegg, the famous pirate.’

The Vicar appeared to be most amazed, as he asked, ‘But what have the mortal remains of Captain Clegg, which in truth lie buried in our churchyard, to do with what you have just been telling me about?’

‘Because,’ replied the Captain triumphantly, ‘through certain knowledge of this Clegg’s activities, and what I have since learned about the Scarecrow, I would stake my last card that they are one and the same. You look astounded, sir, but I had no difficulty in convincing a gentleman I met last night. A very disgruntled gentleman, who had just been put to great indignity and shame by the Scarecrow and his gang, and when I had expounded my theory to this officer of the Dragoons he told me that his brother many years ago had had the same suspicions, but nothing came of it. Nothing may come of this, if the rogue does what I ask him.’

The Captain appeared to have every confidence of success, so Doctor Syn did not protest, but anyone seeing his look of bland astonishment would never have guessed what was really in his mind. But the Captain may have felt something of this, for he rose and sought to take his leave, not without some astonishment that the parson made no effort to detain him or question him further. So, again thanking him for the loan of the sword, he was about to take it up when he noticed on the table where it lay a book. Absentmindedly he turned the leaves as though he was engrossed in his own thoughts. Then closing it with a snap he remarked that it was a very fine translation of the Æniad. Doctor Syn’s left eyebrow rose as he said, ‘Ah, amongst your other accomplishments, I see you are a scholar. I was indeed fortunate to come by so good a copy. Since you are interested, pray borrow it. I will remove my bookmarks. I have an unfortunate habit of making little notes and leaving them all over the place.’

The Captain accepted the book graciously enough and took his leave, riding back to Hythe with his trophies: a useful sword that he wanted and a French translation of a classic for which he had no use.

The family was already at breakfast when Doctor Syn reached the Court House. The meal was very nearly over, but as he was considered one of them only the briefest apology was necessary to Lady Caroline, who insisted on serving him herself. In fact, this morning she seemed very bright and attentive to everyone, in contrast to her usual querulous self. To Sir Antony she behaved with the utmost affection, fussing round him with many a ‘There, my love’, and “A little more, my pet’. She anticipated his every want, which called forth from the Squire when her back was turned at the hot-plate a mighty wink directed towards Doctor Syn, whose obvious meaning was that his yesterday’s rebellion had brought her to heel. The Squire was in excellent humour but for one thing: that those confounded smugglers had had the audacity to use his horses again, and that now when he had got the chance of a good day’s sport there wasn’t an animal fit to ride, with the exception of Cicely’s mare, Stardust, whose stall had been marked with a chalked cross, and she was going to ride herself – selfish girl! Even this was said in jest, for today the Squire could not bring himself to be cross with anyone. Since Doctor Syn’s arrival Cicely had appeared to be intent upon her cup of chocolate, so busily stirring that it was in danger of making all who watched it dizzy, and not daring to look up she had stared at it herself, but knew it was not only that which made her head and heart both spin. Upon her father’s remark, however, about Stardust she glanced up. Doctor Syn was looking at her with a faint twinkle in his eyes, and she returned it boldly, one delicate eyebrow raised. It was lucky that at that moment all the Cobtree family were engrossed upon their breakfast, for the look in Cicely’s eye would not have deceived anyone. It said, triumphantly, ‘So it was you. Thank you.’ Then, as it softened, just, ‘I love you.’

One person at the table, however, was not so busy with her breakfast, nor was she deceived. Aunt Agatha had caught that interchanging glance and knew what it meant. She was delighted, and intended to find out more, wishing that that naughty highwayman had not taken all her jewellery as she would have liked to present Cicely with the diamonds there and then for being intelligent enough to find out what she already had suspected. That behind those great spectacles and air of slow, scholarly charm was an ever-youthful spirit of romance, a great heart, and a quick brain – in fact a man. Aunt Agatha had not been married, but she had an unfailing instinct in these matters. So giving Mister Pitt an extra lump of sugar as a mark of approval that he too had had sagacity in licking the said gentleman’s nose, she purred in anticipation as she promised her own romantic soul much future pleasure in the unravelling of this exciting secret.

After breakfast, however, she had a deal of flutterings on her own account, for upon leaving the morning-room through an ante-chamber, her small white hand through Cicely’s arm, Doctor Syn stopped for a moment to collect some things which he had left upon a chair. He turned to her and with a low bow and an enchanting smile said: ‘A tribute to what every woman should possess, and which you, Miss Agatha, possess in abundance – wit, charm and courage.’ Then, handing her a bundle tied in a silk handkerchief, he said: ‘This with the compliments of Gentleman James to his wee Scots lassie, and this, madame, with mine own regard, hoping I have found a true Scots friend.’

The old lady took the crimson rose and her fingers trembled slightly, her wise old eyes were almost over-bright as, sweeping him the most graceful Court curtsey, she answered softly: ‘I have heard, sir, that all good Marsh men pay their Scotts and so maintain the ancient Wall, but in truth, sir, you have paid such tribute to an ancient Scot that she will ever try to maintain the friendship that you ask.’ Here, curiously enough, she held out her hands to the two of them.

Cicely watched this touching scene and her heart glowed. She applauded his gesture in thus giving the rose where another girl might have been petty, wanting it for herself; and she was amply rewarded, for, taking from his pocket a single glove, he handed it to her and said: ‘And beneath the tree from which I plucked my solitary symbol of admiration for your aunt I found’ – and here his smile was not devoid of mischief – ‘this solitary glove. I fear you have lost its fellow.’

And so it was that in one morning Doctor Syn had bestowed several trophies, loaning the first to a man he did not like and bestowing the others upon two women that he loved. Aunt Agatha had the jewels which she wanted and a rose she had not expected, and Cicely but one glove for which she had no use, yet hoping that the other lay against his heart she thrilled and valued it the more.

Chapter 15

Doctor Syn Receives an Invitation, and Sends One

If Mr. Bone had experiended difficulty in selecting a suitable gift for a lady, Aunt Agatha appeared to be having equal trouble in the choice of one for the opposite sex. Not that her experience was letting her down, but she could not find anything suitable for a gentleman of his profession amongst all this assortment of feminine fripperies. The jewels so lately returned were spread about over the bed, and she turned over and sorted, and then turned over again the objects she had picked out. Cicely sat perched at the foot, leaning back against the spiral post, giving her opinion every now and then. Proudly pinned at Aunt Agatha’s bosom, fastening her fichu, was the gold brooch set with the crystal head of a dog, whose eyes, peeping out from the frills and flounces, were every bit as bright as those of Mister Pitt, who was watching the proceedings from beneath the bedspread.

‘No, child,’ the old lady laughed, ‘not the gold true-lover’s knot – nor the pearl locket with my hair in it, for it might surprise him somewhat to know that I was once a blonde, since he has only seen me in this hairdresser’s contraption. Oh, Lud, had we but something appertaining to his naughty trade – a tiny pair of gold horse-pistols, a mask with sapphires for the eyes – though,’ she added roguishly, ‘I warrant they would not shine as brightly as his do. But there, we have not even a silver spur, and cannot send him a bracelet made of elephant’s hair, since his activities on horseback on Quarry Hill. Steep as it is, ’tis not comparable to Hannibal’s elephantine ride across the Alps.’

Cicely jumped from the bed, exclaiming, ‘Why, Lud, madame, what a ninny I am! Sitting here watching you rack your brains while I believe I have the very thing. I’ll fetch it for you straight,’ and off she went to her own room, returning in a few minutes with something in her hand. ‘There,’ she said, ‘will not this suit your naughty beau, ma’am? At least it tallies with some of his equipment,’ and she held out for Aunt Agatha’s inspection a golden riding-crop set in the form of a pin, its handle encrusted with diamonds and its thong looped in a true lover’s knot. ‘Pray take it, ma’am. ’Tis one I bought myself, after I had first cleared the broad dyke without a splash.’

Aunt Agatha was delighted. ‘I vow, child, and you are quite to my satisfaction,’ she cried. ‘’Tis, as you say, the very thing, though I observe you are insisting upon my sending a true lover’s knot to the gentleman, you wicked miss. And since I am sending him something that belonged to you, I shall give you something that he returned to me,’ picking from the bed a large velvet case which she handed to the girl. Cicely opened it and saw winking up at her a magnificent set of diamond ornaments – necklace, ear-rings and stars for her hair, and being too excited to speak, could only gaze while the old lady continued: ‘Do you not thank me, child? They were to be yours anyway. But now you can wear them at my birthday party. I told your Mamma that she was to excel herself since it will be my eightieth anniversary, and I think I deserve it for staying the course. I intend to write some of the invitations myself, this afternoon. Now let me see’ – and she looked up at Cicely with a twinkle. ‘Is there not some special gentleman you would like me to ask? A beau from Hythe, or a pretty Dragoon from the garrison at Dover?’ Cicely twinkled back at her, but did not speak. ‘No? Well, there are but two gentlemen that I care about in the vicinity. That dear old Doctor Syn and that sinful young horseman, and I vow I shall invite them both.’