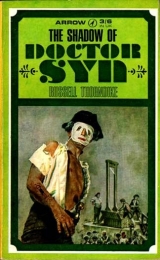

Текст книги "The Shadow of Dr Syn"

Автор книги: Russell Thorndike

Жанр:

Исторические приключения

сообщить о нарушении

Текущая страница: 13 (всего у книги 16 страниц)

The Captain nodded his assent and slipped between the hut and the wall’s edge, whilst Doctor Syn vanished into the darkness of the other side.

What Captain Foulkes now felt was perhaps the culmination of all that he had experienced in his mind since that night at Crockford’s when he had first met this Doctor Syn. Since that meeting it seemed that he was no longer in command of his own destiny and that he was caught in the toils of some vast spider’s web, only subconsciously aware that this black figure was the centre of a patterned weaving, knowing every quiver of it and had almost hypnotized him. So he waited, struggling in his mind, like a stinging wasp, for the right moment to escape the outer fringes by force.

He stood above the sea, watching the fire-play of November lightning round the giant groups of brooding cloud that hovered till some signal should let drive the full fury of their prophetic wrath. Then suddenly, as if they had received a sign, the clouds began to move, and a voice behind him, harsh and imperious, rang out: ‘The Scarecrow waits for no man, Captain Foulkes.’

Foulkes turned and saw what had been described to him a hundred times, though face to face, a hundred times more terrifying, as in this weird setting of the lofty wall, hanging between the clouds and sea, the pitch-torch flickered its unholy light up the gaunt figure to the horrors of its grim, carved face. Even as he watched, It spoke to him again: ‘L’Épouvantail – at your service, Monsieur Barsard.’

The Captain stood silent, his mind too paralyzed to adjust itself to what this strange creature had just said. Then he was asked a question. ‘What is your business with me, citizen, Spy?’ He had no answer. Forcing his frozen intellect to explain how this man knew his secret, he remembered the missing wallet – the highwayman – could he be…? He had heard rumours… But before he had time to reply, as though in answer to his thoughts, the Scarecrow, with a contemptuous gesture, threw something towards him. It landed at his feet – a flat, dark object – his wallet.

He bent eagerly to pick it up, and thumbed it furtively. The paper was still there. Yet this man must have read it; else how could he have known?

Again the Scarecrow answered for him: ‘Yes, I had it from the highwayman. He has sensitive fingers, but cannot read French, though a name is a name to all men, and he is my friend. Doctor Syn told him that you wished it back. The paper is still there, though you will have no further use for it. I do not work through intermediaries. You thought to put a proposition to me, but I did not like your method of approach. To hide a black project behind a bragging wager to kill a wanted man is unworthy of a brilliant swordsman.

‘So the proposal that you thought to make has been attended to, for I do not accept terms – I make them. And I made them to Citizen Robespierre. For though the paper enlightened me abotu a certain Monsieur Barsard, my organization is so complete that I already knew of the scheme he wished to put to me. I went to the head of your organization and he told me what fantastic plans he had. It was simple, because I had already decided to play my part in them.’

Dimly the Captain grasped one thing. It sounded as though this giant smuggler was on their side, and yet he told himself he must be careful. He had made the mistake of approaching him as Foulkes instead of Barsard. But though Barsard’s plans had come to naught, Foulkes still had a card to play, and this he would make sure of. But where was the parson? Why had he not returned? He looked about him, peering into the darkness, anxiously.

Once more he got a reply to his unspoken question.

‘The parson will be with you, Captain, soon. I will bring him back when we are ready, but we still have a few points to clear up.’

Assurance of the parson’s return and what it meant to him restored a little of the Captain’s confidence and he said with some spirit: ‘Since Citizen L’Épouvantail has taken the business out of the hands of Citizen Barsard, I am at a loss to know what other points are left.’

‘There is the vital point of making England revolutionary, and it would interest me to know why Captain Foulkes, a leader of the London dandies, should interest himself in this. Was it perhaps that unfortunate affair that sent you out of the country all those years ago? But after all, that’s no affair of mine. One man’s reason is as good as another’s, and Robespierre too has a reason. He supplied me with six of his best agents. All good spies and desperate characters. I had their full dossiers. Then as I had to make decisions quickly, he generously provided me with yet another – a most enlightening document, taking one from England and a military scandal in 1774 to the Americas – the Caribbean Sea – then back to France – to England and the fashionable clubs with a reputation as a swordsman, and in frequent crossings of the Channel, a reputation as a secret political agent and a denouncer of fostered friends. So, Captain Foulkes, seeing that you and I know so much about this Monsieur Barsard, it will not be difficult for us to keep all seven spies of Robespierre in their place, and if you and I are to work and fight together, I realize that with all that to your credit, I must offer you an equal guarantee.’

The Captain’s spirits soared. If this guarantee was a document similar to his own dossier, why, then he would have no need of the parson’s testimony. But the Captain’s hopes of obtaining such damning evidence were dashed, for the Scarecrow quickly thrust up his right sleeve, and picking up the blazing torch held it over his outstretched arm upon which was clearly visible in the red glow the tattoo mark of the pirate Clegg.

‘Here’s proof enough to kill a man,’ he cried.

Yet again Foulkes had the uncanny feeling that this man could see into his mind, and wishing to be rid of the whole thing and cursing inwardly that now he had to wait for the parson, he tried desperately to plan his next move.

So he prevaricated with: ‘I accept your guarantee, Captain Clegg, for not only is it proof enough to kill a man but proof of many killed. It will be a great day for the Republic when Citizen L’Épouvantail, alias Captain Clegg, is working for them. When do we start? The six others – when will they arrive? Is Decoutier bringing them over?’

‘No, Decoutier is here. He came with me. I brought all six.’

The Captain was astounded. Here was a leader who did not waste time.

‘You brought them?’ he cried. ‘Then we have started already. Where are they?’

‘Here in Dymchurch.’ What happened then was as quick as the lightning which now flashed continually about them, for the Scarecrow’s mask and cloak were tossed aside and there in the vivid stabs of light was Doctor Syn, smiling dangerously. ‘Six spies are in the Court House cells and the seventh is before me. Draw, Captain Traitor, and fight to lose your wager.’

His voice flashed in tune to his movement, swift and thrusting as the steel he held.

For a second Foulkes stood aghast – dumbfounded.

Then about them the storm broke, and with the unleashing of the elements the dark cloud burst in his brain, setting free in clear vision the unaccountable facts of his subconscious foreboding. As easily as the Scarecrow’s cloak was tossed aside to reveal the parson, so did the curtain in his mind disintegrate into one lucid thought – the spider’s web – his destiny. There, at the centre of his weaving in all this tumult of wind and waves, was the black figure smiling at the insect on the fringe of it, who waited, tense and taut, for the first move. Then, as he crouched, watching, the sword of his opponent came to life, flashing blue fire as the lightning ripped along the steel. The wasp struck. With a great cry he slit his blade from the scabbard and leapt forward to the attack. Syn was ready, steel met steel, and for a frenzied five seconds hissed and rasped, as the darts of lightning caressed both blades, spurting from point to point.

A double thrust from Foulkes was parried by Syn. He laughed above the wind wildly and with satisfaction as Foulkes leapt back. Here was a swordsman who could make a fight. Now the lightning seemed to be coming from his eyes. He waited, alert – poised for the next move. It came slowly, blades pressing and sliding in a husky whisper. Still Syn did not attack, holding a stiff defence, and the eyes of the two men burnt to each other’s brains, trying to read the command before it reached the blade. Foulkes thought he knew Syn’s plan. To wear him down and thus keep fresh himself. He did not fear that strategy. A younger man than Syn, he knew, could outdistance him in playing a long game, counting on well-trained strength and breathing power. If Syn would not attack, why then he would, showing what speed could be. He leapt and thrust, seeking some weakness in the guard that faced him, but meeting that same baffling calm now so familiar to him. He rushed in now like a lithe bull, hoping to break down the defence by weight. Syn leapt aside with riposte, but if Foulkes thought he was wearying him, he found that he was wrong, for suddenly Syn was at him in attack and Foulkes was driven back before this amazing speed. Then for some minutes the blades clanged and sputtered and the sword-thrusts moved and lunged in broken rhythm as the shooting steel licked in and out, and the torches held high in hand with curved left arms, wreathed smoke about the fighters’ heads. And up and down and round upon that flat sea-wall, they traced their wild manœuvring in the close-cropped grass – fighting now by torchlight, now by lightning-flash, sometimes almost in darkness. The attack stopped as suddenly as it began, and Foulkes was once more met with Syn’s immovable security. Angered, he attacked as furiously, but this time Syn began to give him ground, and Foulkes thought: ‘Ah, he is the older man. He will not stay the course.’ And so it seemed, for the retreat went on, with Foulkes unflagging – driving. Once only did his opponent seem to stop, for some few seconds, but then the retreat continued, and Syn knew that his opponent had not noticed what he did, for in those precious seconds, knowing the ground, Syn’s left foot, behind him, felt and found what he had sought, and measuring it mentally aby stepping back, let the retreat go on. Foulkes, thinking this the beginning of the end, pressed on with confidence, hoping with every thrust to break the guard and draw first blood. Slowly Syn backed and backed. And Foulkes, not daring to disengage his eye from Syn’s was puzzled by the change of texture on the ground. They had fought in grass, but now they fought on wood. The wind here had more power, as though they were exposed on some high place. He longed to look about him, and cried, with clenched teeth and staccato voice, ‘Where are you driving me, you devil!’

A calm voice answered him. ‘It seems that you drive me. But have a care. Fight straight. We have a bare four feet. A sheer drop either side.’

It was then that Foulkes heard above the wind the rushing torrent of dyke water meeting sea, and he realized with sickening horror that they were fighting on top of the Sluice Gates. He remembered them, and thought of the black malevolent ooze so far below. He knew he had been trapped, and rage, blacker than the mud, filled him. Watching Syn’s eyes he suddenly flung his burning torch straight at his face. Syn saw it coming like a meteor. No room to step aside, his mind and sword were simultaneous. His blade flew up and with the flat he struck the flying missile, sending it hurtling overhead to fall in an arc of fire sizzling in the sea. He felt a sudden numbness in his hand as Foulkes’s thrust caught his upturned arm. By the look in Foulkes’s eyes he knew that he had fouled to make him drop his sword, and was waiting then to pounce and murder. But Syn leapt first, and with a throttled cry Foulkes dropped his sword with Syn’s blade through his neck, and clawing the air fell backwards into space, a long black fall and then – a blacker death.

From the great height of the Sluice Gates Syn looked down, holding his torch far out, its flickerings reflected in a million times in the creviced liquid below. No darker shadow on the shining surface of the fermenting kiln; but where he looked giant bubbles rose and sank, as the undulating mud rolled back to place.

Then high and shrill above the whining of the wind and borne aloft on unseen wings, the curlew cried three times.

Chapter 20

A Brand New Box of Soldiers

Thomas was late. ‘Boots’, who should have called him, was late. In fact, everyone was late. But as the Squire was still asleep, nobody had as yet been blamed. Thomas, expecting his ears to turn crimson any moment now and knowing that there is always a calm before the storm, tiptoed past the somnolent bulk of the Squire in the middle of the four-poster bed and opened the shutters. He made a deal of noise and coughed discreetly. The Squire groaned and slept on. Thomas, grateful for this short respite, busied himself about his master’s room, retrieving various garments that had somehow got themselves into the most extraordinary places. At last all were accounted for except the wig and one buckled shoe, so being accustomed to this eccentricity, he looked in the most unlikely places. The wig revealed itself, perched rakishly upon the candle sconce which lit the Squire’s most unfavourite portrait of his great-aunt Tiddy. The shoe was nowhere to be seen, though it came to light later in the day at the end of the Long Gallery, whither Sir Antony had flung it at the retreating Mister Pitt. The Squire rolled over and humped upon his face. Thomas could not postpone the evil moment any longer, so with the remaining shoe still in his hand, he gave the lightest part of the hump a resounding thwack. This having the desired effect, he stood at a respectful distance, his ears flushing in anticipation. The hump subsided. The Squire rolled over and scratched his chest. It crackled, and woke him. He yawned and said: ‘Thomas, you’re late. Tell Mrs. Lovell not to put so much starch in my nightshirt.’ He scratched again, let out an oath, and sat up, sucking his finger. Thomas, haveing seen something most unusual, and fearing to be blamed for it, fled. The Squire flattened his chin and looked down his nose, and saw that pinned to his own nightshirst was a folded paper. He continued to look at it, trying hard to think what he had done last night, but as the only thing he could remember doing was betting Sir Henry that he wouldn’t stick a feather in me wife’s Aunt Agatha’s wig, then chasin’ that stinkin’ poodle up the back stairs, he reserved judgement on the matter. He continued to squint and peer but couldn’t read it. ‘Damn fool pinned it the wrong way up,’ he muttered. Then, pricking his double chin in and extra effort, he located the pin and pulled it out, wondering why he hadn’t thought of it before. What he saw made him leap out of bed and go to the window for better light. But there it was, the picture of the Scarecrow, and he could read the large scrawled writing without his glasses.

Dear Squire,

Here is the Seventh. For Rogue, Scoundrel, Rascal, aye, Sir Antony, even Smuggler I may be, but the Scarecrow has always ruled ‘Death to a Traitor’. Here was a Traitor to England whose body may be found in the mud of the Great Sluice Gates, but whose dossier signed by Robespierre might interest Mr. Pitt, Minister of War. I wished to pay you this further service because this man denounced the Comte de Longué, your daughter’s husband. Hoping that my act will gain for you much honour and not another proclamation for me,

I remain your Disobedient Servant,

THE SCARECROW.

Sir Antony was delighted. He started at once composing fresh speeches to Mr. Pitt and then, wishing to rehearse them, trotted out gaily to the gallery, oblivious to the fact that his feet were bare and he was clad in nothing but a nightshirt. He called all to him, but since everyone was asleep nobody came, and a sharp yapping reminded him of bare ankles and warned him to scurry to cover.

Thomas, returning apprehensively, found him all smiles, and was chagrined to find that his ears had already responded to disaster.

Sir Antony, bursting out of his London clothes, for he had put on several inches in the wrong direction since he had last worn them, was conscious of a pressing top breeches-button, and was equally bursting with a pressing desire to impart his good news to all and sundry. But he had a lonely breakfast because everyone was late. Indeed, Cicely was the only member of the family who eventually appeared. But he was so overjoyed at having someone to talk at that he failed to notice her grave expression when, on reading the letter to herself, she saw something which he had also failed to notice. On the back of the scrawled note was something that possibly even the sender had overlooked – a dark stain, which could mean only one thing – blood. Whose? Her heart pounded. So, kissing her father fondly, she told him to behave himself in London, and to say to Mr. Pitt whatever came into his head first. But whatever he did say she was very proud of her dear Papa. Would he please excuse her, for she had an appointment with Stardust? But once out of the house she fled across the Glebe field and by the sea-wall to the Vicarage….

After much fussin’s and fumin’s and losin’ of tempers – forgettin’ this and that, and remembering a lot of unnecessary instructions – the Squire was launched by the remainder of his long-suffering family. With delicious thoughts of freedom ahead, London and his position fully appreciated, absence of restrictions regarding port and the naggin’ that went with it, he allowed himself further mental licence – a flutter at Crockford’s and perhaps – why not? – a visit to that stunnin’ charmer – what was her name? – Harriet. He settled himself comfortably in his State Coach pulled by the best cattle in Kent – with Thomas in smart livery on the boot – and was further delighted by the loyalty of his tenants, who had come to cheer their benefactor and Squire on his departure for the Court. He was under the fond impression that the village knew nothing of the French spies and had simply come to watch his grandeur. Actually there was very little that the village did not know. So tho’ it bobbed and cheered as his equipage rolled off in style, it was in a very ferment of excitement this morning.

Cicely tapped on the Vicarage door and got no reply, so she went round the windows and peered in, only to be met by teasing shutters. But the library window was unshuttered and unlatched – in fact, it had an enticing chink. She had therefore hitched her dress high up round her waist in a most unladylike fashion, showing not a little pretty lace and frills, and was in the act of balancing one foot upon the water-butt and t’other upon the sill, when a voice behind her startled her into a sitting position on the flower-bed beneath:

‘Now then. This is a ’oly residence – no place for showin’ yer dicky-cum-bobs. There now,’ it went on, ‘now you’ve gone and hurt them on them bulbs – ’urt them bulbs too – ’urt yourself?’ She turned and saw the Sexton watching her critically with cocked head.

‘Oh, Mr. Mipps,’ she laughed. ‘How you did surprise me. If it hadn’t been for these confounded petticoats I should have been through the window before you could bark.’ She got up and brushed herself, then became more serious. ‘Mr. Mipps,’ she said, ‘is Doctor Syn all right? I have a strange feeling that he may not be very well this morning.’ Immediately Mipps was on the defensive.

‘Now whatever put that into your ’ead, miss – he’s never ill, he ain’t.’ Then, seeing her glance up to the Vicar’s still curtained window, found excuses. ‘Oh yes, miss, it is late for him, I knows, but he was out visiting Mrs.… Mrs.…’

‘Mrs. Wooley, Mr. Mipps?’ put in Cicely, with raised eyebrow.

‘Er – yes, miss – thank you, miss – poor Mrs. Wooley, miss.’ Mipps might have gone on enlarging upon that same old body’s complaint, but again she cut him short.

‘I just wondered, Mr. Mipps.’ She looked straight at him and he wriggled. ‘For I could not sleep last night, and from my window early this morning I saw strange lights in the direction of the Sluice Gates – surely that is not the direction you would take to visit her? But there, I would not pry – so if you promise me that the Vicar is quite well, why then I will not break into the holy residence.’

Mr. Mipps assured her that indeed Doctor Syn was quite well, but that the poor old gentleman was having a nice long rest after his dancings and goings-on. Then, sticking firmly to his guns, though with a suspicion of his famous wink, added, ‘And it’s a long ride to Mrs. Wooley’s….’

Cicely smiled at him and loved him for the stubborn little watchdog that he was. So, telling him to inform the Vicar that if he cared to begin his riding lessons that afternoon she would bring round Stardust and another mount, though perhaps he was not quite ready for the broad dyke jump, and she would bring the quietest in the stable. Then she was gone, sauntering across the bridge. But she turned half-way and called to the still waiting, staring Mipps:

‘Pray tell the Vicar that should he not feel well enough for his riding lesson, why then I shall visit him this evening with words of cheer – for I have my duties too as Spinster of the Parish….’

Through his window Doctor Syn, lying comfortably in his bed, had heard the passage-of-arms between his best-loved friends and loved them all the more. He had a mind to leap out from the window to the bridge and take her in his arms; but feeling as he did, relaxed and quiet – though his slight wound was painful – his heart was so full for her that all he wished to do was to lie and absorb her into his very soul. A great danger had been overcome, was past, and now he thought he could afford to wait. So there he lay and pondered on the glorious possibilities ahead, weaving yet another pattern into his ill-starred life….

Cicley strolled back through the village. She had no mind to hurry; indeed her mind was so completely his that until she saw him she must be alone; she wanted to recapture that glorious emotion of being one detached from earth, and the spirit guiding her took her to the Tower. She neither saw nor heard the many villagers who greeted her, and her expression was so beautifully remote and yet so shining that no one dared to break it; but after she had gone they whispered delightedly that ‘For sure the Squire’s youngest was in love and they knew who.’ Had they not seen as pretty a picture as they ever hoped to set eyes on, the very night before, when their beloved Vicar had led her out to dance in all her golden youth? So the gossips prattled, discussing every detail of the gay proceedings, from the little old lady’s courage to the merry impersonation of the Shadow. Though when they fell to talking of the second appearance of their idol that night they became venomous. That prowling Mr. Hyde and seek – which name, attributed to Mr. Mipps, attached itself and stuck. So the Sandgate officer of Revenue did not have a very pleasant time in Dymchurch that day, for having decided to put a bold face on it, he stayed to watch, trying to pave his way with pots of ale. But nobody seemed thirsty. Fishermen came into the Ship Inn and greeted each other with, ‘What was your catch today? Did you set a sprat to catch the Scarecrow? What did you get, mackerel?’ He decided not to notice – but even the children in the street ran after him, begging him to join their games of Hyde and seek.

But indeed there was another reason for gaiety, for was it so rumoured that the Dragoons had been recalled to Dover, and that Major Faunce and his men would soon be off to France? For a while they were full of patriotic feeling towards these gallant soldiers, they also secretly rejoiced that now questionable activities would not be hampered. This did not seem to be so secret either, for was not practically the whole village in the Ship Inn celebrating their departure?

Few of the ‘Ship’ staff in the kitchen that morning recognized a smart young officer in a new uniform who put his head in at the window and greeted them, though it did not take them long when they looked more closely. ‘Why, goodness me, if it ain’t that young gentleman what breakfasted with us about a week ago.’ And so it was – Lord Cullingford who had been posted to that regiment, and who had lost no time in reporting to his commanding officer, Major Faunce.

Later that morning, as the Vicar sat in his comfortable library, Mr. Honeyballs announced a visitor. He was sincerely touched and very glad to see Lord Cullingford. The boy had stood before him, straight and fresh, and Syn had laughingly remarked upon the fineness of his uniform – but knew it was not that which gave him this new spirit. He had indeed and upon that moment thanked his Maker for allowing him to have been the humble instrument for its attainment. Then the boy had handed him a packet in repayment and he knew the value of trust where trust was due.

So the mounted regiment made brave show as, with drums and fifes before them they took the Dover Road. But although they understood the cheers they received, they saw no humour in the tune they played, which every British regiment follows when going off to join the wars. But the village seemed to find it funny, for it rocked and whistled and held its sides with laughter and helped to swell that merry tune ‘The Girl I Left Behind Me’.

Yet hardly had this murmur died down when through the village from the other side came marching in a brand new box of soldiers.

Chapter 21

Mr. Mipps Remembers to Forget

Mr. Mipps was highly indignant. He cursed himself for a ‘dawthering old sone of a sea-dog’, and then, correcting himself, said he was a ‘chiddering1 old landlubber’. He might have known the Captain always kept his porthole open. If only he hadn’t been so addle-brained, he might have wheedled Miss Cicely round to the other side of the house where there would only have been Mrs. Honeyballs to overhear, the old Keg-Meg.2 ‘Ridin’ lesson! My baggin’-’ook,’ he muttered to himself. ‘If the Vicar goes on bein’ funny about it, I’ll tell him that “evesdrippers3 never hears no good of theirselfs”.’ But there it was, the Captain had overheard. And here he was on his way up to the Court House with a message: ‘The Vicar will be pleased to take his ridin’ lesson with Miss Cicely this afternoon at half past two.’ Mipps was really worried. The Captain hadn’t had no proper sleep for nights – he’d gone out and got himself pinked. Now Mipps wanted him to rest, and here he was behavin’ like a flirt-man.4

Mipps had reached the Court House in such a dobbin that he’d given his message to the first person he saw. It happened to be Aunt Agatha, who could hardly believe her ears, when having delivered the message he looked straight at her, through her, and past her and muttered, ‘Dawtherin’ old chidderer.’ Miss Agatha felt quite sure he did not mean her, for he pulled his forelock most respectfully and stumped off to the churchyard. Whatever Aunt Agatha felt she most certainly gave the message, for at half past two, most precise, Cicely arrived at the Vicarage on Stardust and leading one of the Squire’s most spirited horses.

Even Mr. Mipps had to admit that Doctor Syn put up a good performance, for he had approached the animal with a fine show of apprehension, patting it timidly and, after many vain attempts, climbing clumsily aboard.

‘Play-actin’,’ Mr. Mipps called it, though as he watched them riding off together he felt so strangely moved that he had to give himself a wink and a nip to get over it.

1 A chidderer is a booky.

2 Gossip.

3 Mr. Mipps’s word for eavesdroppers.

4 Ladies’ man.

So they had ridden through the village where the Vicar made much ado about stopping and starting Red Pepper when greeting his amazed parishioners. His foot slipped many times from the iron and he held the reins as he had seen Mr. Mipps do on Lightning, Cicely watching with very bright eyes this delightful clowning for her benefit. Then they were free of the village and out upon the lonely Marsh, setting their horses towards Lympne Hill. The storm of the night before had exhausted itself with its own fury. The hill shone birght in the pale November sun, yet when it shone on Cicely’s red-gold hair and russet riding-habit, it seemed she warmed the sun to summer. They had not spoken. Indeed they had not looked at one another; but now, the last farm passed, with it went ‘dear old Doctor Syn’.

He straightened in the saddle and took command of the surprised animal. Then turning to her, deliberately took his spectacles from his nose and grinned boyishly – and they were off. The horses were as well matched as they, and neck to neck they galloped deliriously. Over this dyke and that, across broad fields, scattering the sheep, and on they sped, gathering momentum towards the Broad Dyke.

A watcher, who was ‘lookering’ his sheep and loved good horses, watched them, fascinated, clearing this wide, deep canal together in perfect rhythm, horses and riders in unison. Then straight ahead and up the slopes they climbed towards the Roman Camp, above which frowned the perpendicular wall of old Lympne Castle. Here they dismounted and let their horses graze on the lush pasture that centuries ago had been beneath the sea, while they sat down, glowing and happy, on the harbour wall where galleys once were tied, as if each to the other had belonged since those old days, united as they had been on their ride.

There they sat with all the quietness of the past about them, looking at this vast sweep of land divided from the sea by that straight wall. This was his country – here he ruled from two extremes and she sat by him like his consort.

The sun flashing on lattice panes far below brought to her mind another flashing light, and she told him what she had seen that morning early, demanding what he did and why he risked his life – for she told him she had seen the Scarecrow’s letter to her father. Gravely he asked her if she remembered the conversation at dinner the night before about the rumoured pardon of this rogue, saying that now he must do all to gain it, and since this Barsard had been an enemy of England his chance of winning it was therefore greater. She remembered, she said, but she wished to forget – and he smiled at her using his own phrase; and to all his arguments on that count she would have none, saying that she loved him as he was. She bade him be silent about his past, for all she wanted was the present – looking at him almost questioningly till he wrinkled his brows, wondering if she were finding some fault in him, though she was but marvelling at this strong, strange man who was able by sheer force of character to hide that side of himself which was his best under the cloak of age. Yet she knew that if she had her choice she would not have him otherwise – she never had, she never would. Then suddenly she began to laugh. He watched her lovely merriment and sought the answer with one raised brow. She told him how since she had been quite small she used to borrow Mr. Mipps’s spy-glass to watch him sitting on this very spot. ‘The glass was magic and brought you to me right across the Marsh.’