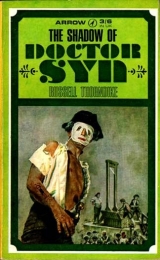

Текст книги "The Shadow of Dr Syn"

Автор книги: Russell Thorndike

Жанр:

Исторические приключения

сообщить о нарушении

Текущая страница: 4 (всего у книги 16 страниц)

‘I am extremely sorry, my dear Jimmie,’ Doctor Syn was saying, ‘but I had no idea that the old lady would be travelling by that coach. May I suggest, since the Cobtrees are such friends of ours’ (at which Mr. Bone grimaced appreciatively, thinking of the many broadsheets Sir Antony had put out against him), ‘that we have a little private transaction. You being as good a valuer as any of the Receivers, what do you estimate they are worth to you?’

Mr. Bone threw back his head and pulled at his ear as he made rapid mental calculations, but upon realising the full significance of what the Vicar had in mind, brought it sharply back again with a quick retort. ‘Oh no, you don’t,’ he cried. ‘If you’re thinking of buying back the old Scotch lassie’s jewellery and are a-thinking that I’d let you do it, then my name’s not Gentleman James. I liked her so well that I came here tonight with the lot in my pocket, so will you kindly do me the honour of getting them back to her with my compliments? I should like to have done it myself, but my presence at the Court House might have embarrassed the Squire.’ At which statement Mr. Bone smiled somewhat ruefully, thinking that perhaps after all the life of a gentleman of the road was rather a lonely one. Doctor Syn thanked him warmly, knowing it was hopeless to argue further against his friend’s generosity. ‘Besides,’ went on Jimmie Bone, ‘I shall have made a tidy profit on the effects I lifted from that swaggering Bully.’

‘Upon which,’ put in Doctor Syn quickly, ‘I shall refuse to take my tithes.’ And they both laughed heartily.

But the Highwayman’s voice took on a more serious note as he asked, ‘What do you intend to do with the blackguard, since you told me of his wager to catch the Scarecrow? The blustering fool. As if he had a hope in hell. Would you like me to deal with him?’

‘Time enough to think of that, my dear James,’ replied the Vicar, ‘but there is something I would like. A glace through the papers in his wallet.’

‘Easy enough,’ said Gentleman Jim. ‘’Tis intact save for the paper money which I changed into gold before it could be traced.’

‘A wise precaution,’ laughed the Vicar. ‘’You’re incorrigible, Jimmie. For here I find myself aiding and abetting when I should be showing you the errors of your ways.’ Saying this as he went through the wallet quickly, and finding the paper he required, handed it to Mr. Bone for his enlightenment.

‘An I O U for a thousand pounds, eh? From my Lord Cullingford. Is your reverence about to aid and abet some other arrogant fool?’

Doctor Syn shook his head. ‘No, I intend to show that misguided fool the error of his ways and make him mend them.’

‘And I have no doubts but you will do it good and proper, and by the time you’ve finished with him he’ll be glad to follow the straight and narrow path.’ Mr. Bone, glancing at the wallet which the Vicar had returned, remarked: ‘’Tis so full of other I O Us that he’ll not miss a paltry thousand. And since you’re about to help this wayward youngster, I’ll follow your example and relieve the others,’ and he threw a fistful of scribbled slips into the fire.

Thus dismissing the subject of the coach and its occupants they fell to discussing more serious matters, plotting the manner of the ‘runs’ for the following week, and the false ‘runs’ that should precede them, to throw Major Faunce and his Dragoons on a false scent.

Mr. Mipps, having cleared the refectory table, unrolled a large survey map of Romney Marsh, pinning it flat for easy perusal. Over this they stood, while Syn’s long, pointed finger moved this way and that, as he unfolded his plan of campaign and fully explained his tactics. Indeed they looked for all the world like generals setting their plan of action before a major battle, while Mr. Mipps, as fussy over details as any aide-de-camp, followed the series of actions, making copious notes and rough diagrams in his undertaker’s notebook. Thus they worked for an hour or so poring over maps, listing movements of the ships and cargoes, settling the number of pack-ponies required, and discussing the merits of local horses necessary for the night-riders. Not that the Scarecrow depended upon the contents of his followers’ stables. Far from it. He had imposed a custom that had become almost a law, for by the ingenious method of various chalk-marks upon stable doors, the ostlers, who for the most part were in the game, saw to it that the doors were left ajar. Indeed, many a fine gentleman, even the Squire himself, spoiling for a good day’s sport following hounds, had, much to his chagrin, found himself mounted upon a tired and jaded animal, who, by reason of its equine inability to gossip, was unable to inform its spurring master of the questionable activities it had been forced into all night.

Their plans completed and the maps put away they had a hasty meal, washing down an excellent cold collation with fine red wine from Burgundy.

‘And will you be needin’ Buttercups tonight?’ asked Mr. Mipps.

‘Yes, indeed, Mr. Mipps,’ returned Dr. Syn. ‘And the panniers packed. You know I go a-visiting.’

‘Visitin’ my – ’Ave some more cheese, sir? Old Mother ’Andaway, o’ course. Worst of these false runs, which I owns is necessary for the foxification1 of authorities, is that you has the same dangers but hasn’t the happlause what goes with the openin’ of a cask. Oh well, we’ll stow away now. By the way, sir, what about them you-know-whats? When are you goin’ to fetch ’em from you-know-where?’

‘That’s all settled Bristol fashion, Mr. Mipps,’ replied the Vicar as the Sexton refilled the glasses. ‘I found occasion to visit our old friend Captain Pedro whose vessel lay in London Pool. He will by this time have already sailed and is expected across Channel.’

‘Why, blow me down! That takes you back. Pedro, me old amigo. Remember what he done up in Tremadoc Bay?’ And Mipps plunged back to reminiscences of this old and trusted member of the Brotherhood. Indeed they became so engrossed that it needed three cries of the curlew to bring them to their feet. Mipps to the stables to saddle the Vicar’s fat white pony, Buttercups, while Jimmie Bone handed back the old Scotch lassie’s jewels and took his leave, after settling his rendezvous for the following day. Doctor Syn went up the first flight of stairs where on the landing stood his old sea-chest. From this he took a selection of queer garments, strange comforts for the sick old body he was about to visit, anyone might have thought who could have seen him later filling the baskets that hung on either side of his pony’s saddle. Thus it was that the Vicar of Dymchurch on his fat white pony, followed by his Sexton astride the churchyard donkey, Lightning, ambled along the Marsh road, bidding a cheery good night to a picket of Dragoons, who marvelled at the old gentleman’s fortitude when they themselves were feeling none too courageous as they watched for any signs of the Scarecrow’s ghostly riders through the shifting curtain of sea-cloud. Indeed, such courage as they had completely left them when but a few minutes after the fearless old gentleman and his whimsical follower had disappeared, there came upon them suddenly, out of the encircling mist, a wild apparition-hideous face gleaming with a phosphorescent glow – it seemed to be one with the fiendish black fury it rode. In a panic, the terrified Dragoons leapt into the nearest dyke, while thundering hooves skimmed their submerged heads, and unearthly cries screamed away into the night.

1 Mipps’s own word for being fooled.

Chapter 6

In which Lord Cullingford Gains More Than He Loses

Upon leaving the Vicarage where he had been not a little irritated by the feigned stupidity of that odd-looking servant with the ridiculous name, who, he felt, knew more than he cared to impart concerning the Vicar’s return, Lord Cullingford, forced by hunger, betook himself back to the Ship Inn. Indeed, he had eaten nothing all day, having spurred his horse to its extreme limit to reach Dymchurch before Captain Foulkes. So feeling low not only in body but in spirits, he walked the short distance through the village and was conscious that all eyes were upon him. It was extremely disconcerting as he passed by cottage windows to know that the curtains were being furtively peeped through, and that his presence was being discussed by the invisible inmates. His feeling of discomfiture increased, however, when upon gaining the fastness of the ‘Ship’ and getting no attention in the coffee room, he had, perforce, to go into the bar parlour which up to the moment of his entrance had sounded like a veritable Tower of Babel. On his appearance this noise suddenly stopped, as again every eye was upon him, and our fine gentleman, wishing that he could vanish through the floor, had to shoulder his way through closely knotted groups of yokels who watched him with stolid amusement, whilst those who had any liquor left in their tankards emptied them quickly, hoping by this to convey their meaning to this finely dressed gentleman who, they felt, should buy his intrusion with a free round of drinks.

Scanty as his purse was, the same idea had occurred to Lord Cullingford, who by this time was feeling the dire necessity not only for a drink himself but for a few words of cheer, so with an authority he did not feel, he called loudly to the stout lady on the other side of the counter. Whereupon the crowd seemed to surge round him the closer, tankards were thumped on the bar and many voices cried out, ‘Missus Waggetts. Wanted. Gentleman’s orders.’

‘Comin’! Comin’! ’Ere I be,’ and the enormous proprietress bustled to that end of the bar and began filling innumerable tankards, which operation, taking considerable time, it was not for ten minutes that Mrs. Waggetts, almost as an afterthought, asked if there was anything he required for himself. So, not wishing to be thought superior, he ordered a tankard of the same, and upon tasting it found that it was heavily laced with brandy, which though not displeasing on his own account, being the very thing that he needed, was, he thought, taking his generosity a trifle for granted. However, putting a good face on it, he flung a guinea on the counter, and making sure that this time he would not be misunderstood, he ordered himself another glass of brandy with a request that the food should be served to him as soon as possible in the coffee room. But half an hour later Mr. Mipps, overcome by his insatiable curiosity regarding the Vicar’s unusual visitor, walked into the bar parlour himself and found Lord Cullingford still indulging his newly acquired taste for beer and brandy.

‘Why, blow me down and knock me up solid!’ exclaimed Mipps, ‘who would have thought we’d meet again so soon?’ But he did not mention that he had come there expressly for the purpose, having been told that the young dandy was in the bar parlour at the ‘Ship’ and was pushing out the boat, which indeed Lord Cullingford, must to his surprise, found that he had been doing steadily since his first order. By this time, however, having grown somewhat reckless, he had thrown caution to the wind, several other guineas on the counter, and again to his surprise discovered he was enjoying himself. So greeting Mr. Mipps almost as a long-lost friend he called to Mrs. Waggetts to supply him with a good measure. Mr. Mipps winked at Mrs. Waggetts. Mrs. Waggetts winked back and served him with a double noggin of brandy neat, which the Sexton tossed down in one, and pushed the glass forward for another, apologizing for his undue haste and remarking that he seemed to be a bit behind the others.

As soon as he had caught up to his satisfaction Mipps paused, and, after surveying Lord Cullingford attentively, remarked: ‘Well, well, now whatever should bring a fine young gentleman like yourself down to the seaside at this time o’ year? If you’re thinkin’ of indulgin’ in that there new-fangled bathin’, you’ll find it ’orrible cold. Or was it fishin’ you was thinkin’ of? Our Dover soles is famous.’

‘If it’s fishin’ he’s thinkin’ of,’ chortled an old crony, ‘he’ll be after something bigger than them Dover tiddlers, I’ll be bound. I do ’ear tell that several London gentlemen ’ave a mind to go a-fishin’ for our Scarecrow. ’Tis a tidy reward they’d get, and p’raps London ain’t so full of guineas as they wouldn’t want to earn it.’ Which remark being exceedingly pertinent to his lordship, warned him to keep his own counsel, so he did not rise to the bait, and fortunately enough, before the inquisitive yokels could question him further, the conversation was interrupted by the arrival of a Sergeant of Dragoons with half a dozen troopers, who came in for the probing badinage and facetious heckling which otherwise might have been directed towards him.

‘’Evenin’, Sergeant,’ said Mr. Mipps. ‘Found what you’ve been lookin’ for, or ain’t you been lookin’ today?’ The red-faced sergeant swung across the bar parlour, spurs jingling and banged a gauntleted fist upon the counter, as he called for drinks. His attitude was that of a pugnacious game-cock, which, though it did not intimidate Mr. Mipps, had the power of paralysing his enormous troopers.

‘We don’t want none of your quips and quirks, Mister Sexton,’ he snorted. ‘We’ve been out today and well you knows it. Though we didn’t find what we was lookin’ for, we finds out quite enough to help us to go on lookin’, and if I knows anything about the look in Major Faunce’s eye, we’ll be out again lookin’ tonight.’

‘Well, they do say,’ croaked the old croney in the corner, ‘that there’s none so blind as them as looks and can’t see.’ And so it went on, the yokels baiting the red-coats who generally came off worst. Indeed, had not Mrs. Waggetts’ beer been of such excellent brew, some pretty quarrels might have ensued; but its soothing qualities acted quickly on the tired Dragoons, and, putting them in good humour, the sallies were taken and returned in good part.

Lord Cullingford, used to the polished wit of the London exquisites, was bored with the crude clowning of these bumpkins, and welcomed the news that his dinner was ready in the coffee room, where he was delighted to find that the fare, though simple, was yet well cooked while the cellar list might have put most London taverns to shame.

The only other occupant of the coffee room was an officer of Dragoons who for some time was engrossed over military papers at the far end of the long table, but upon the serving-wench bringing in his dinner, he moved nearer to Lord Cullingford and the two were soon engaged in conversation. Major Faunce, although an older man and a typical soldier, possessed a manner both frank and engaging, and Lord Cullingford was relieved to find someone of his own class who seemed eager to converse upon the one thing which his lordship most wished to hear – namely, the Scarecrow.

‘Though I have been over here but a week,’ Major Faunce explained, ‘I have learned to appreciate the difficulties before me. The ways of the Scarecrow and his gang are devilish tricky, as my own brother knew to his cost. Many years ago that was, too, and since then the organization has been so built up that I don’t believe anyone will stop it. Still, orders, you know. Though as far as I’m concerned I shall be glad when I’m ordered to France, for I’d rather fight the Frenchies than have to deal with this hole-and-corner business.’

Which statement served to plunge Lord Cullingford back into his former despondency. And it was not until the Major said that he had received information that there was to be a run tonight and that he hoped for some action, that he saw again some ray of hope, and indeed his spirits soared when the Major laughingly suggested that if he wanted a good ride and had no objection to jumping a dyke or two, he might care to come along and see something of the Scarecrow’s work.

‘Though, understand me, sir,’ concluded the Major, ‘I cannot promise that we shall see a thing.’ This offer Lord Cullingford accepted eagerly, though protesting that having ridden from London that day, his acceptance must depend upon the condition of his mare. And warming to the subject, having for some time been in sore need of a confidant, he found himself blurting out the full extent of his difficulties and the reason of his visit to Dymchurch.

The kindly soldier treated him as he might have done a somewhat foolish younger brother, and though he may have been secretly amused at the thought of this stripling confronting the Scarecrow and succeeding where so many accomplished men had failed, he did not show it.

‘Let the youngster ride out with us tonight,’ he thought, ‘and he’ll soon see the impossibility of succeeding, and go squealing back to London with his tail between his legs.’

So he treated the boy’s confidences in a sensible way, proffering the loan of one of his own chargers if the mare was spent.

And so it was that some hours later Lord Cullingford, freshly mounted, rode with the Dragoons. Trotting at Major Faunce’s side he felt an exhilaration he had not experienced before. This was a different type of horsemanship to the foppish caracoles he was accustomed to in London, and a fresh loathing of his squandered opportunities and meaningless life seized him. He looked back at the troop, and the moon, appearing from behind the driven clouds, flashed on breastplates and trappings and lit up the crested helmets, under which the faces of the men held firm by tightened chin-straps were set into lines of determination and became to Cullingford symbols of purpose.

Although for some time they encountered nothing tangible, yet there was an air of expectancy on the Marsh that night, as if behind the shifting spirals of low-lying mist strange activities were about to be set in motion. Even the cries of the night-birds sounded ominous, and seemed to be woven into some furtive pattern, as if all were awaiting a master signal. The cry of a curlew surprisingly near was echoed at intervals into the far distance, each mocking note being answered back by the satirical hootings of an owl, so that the soldiers felt as if they were being made the target of some vast jest.

As indeed they were; for though the purpose of the night’s mobility was but a practice for the smugglers, and a valuable one at that, since it enabled them to test, without the risk of losing contraband, the best way to tackle the ‘run proper’, yet they saw to it that the Dragoons were fooled into thinking that this exercise was the real thing. So following false trails the soldiers were led on by a tantalizing will-o’-the-wisp, in and out the shining patchwork of the moonlit dykes.

And then from lofty Aldington that towered above them there shot to the skies a mighty flame. The beacon had been lit. Signal received – the whole Marsh came to life. Luggers off-shore put in, and empty barrels were swung into place. Strings of pack-ponies appeared, and, quickly loaded, were herded off in various directions, whilst circling the whole manœuvre were the Nightriders, hooded and masked, and mounted on the swiftest horses and uttering wild cries, and looking like a host of demon riders, enough to quell the stoutest heart.

Major Faunce, swinging his sabre as signal for attack, called to his men, and the whole troop charged; yet as hard as they rode, the Nightriders, led by the Scarecrow on his plunging black horse, Gehenna, outpaced and outwitted them. Across flat fields and over dykes went this mad cavalcade, till the bewildered Dragoons, breaking formation and riding each man for himself, were scattered, and the whole Marsh was in confusion. Shots were fired, and terrified sheep stampeded under the whistling bullets, hampering the cursing horsemen.

It was during this wild skirmish that Lord Cullingford, riding a horse he did not know, misjudged a jump and was heavily thrown.

Upon regaining consciousness, his first impression was that this must be Death, and worse, it must be Hell. He was in the Infernal Regions, surrounded by demons and ghouls, and confronted by the Archfiend himself. His lordship closed his eyes, hoping the nightmare would vanish, but on hearing a harsh voice cry out ‘Next,’ he opened them again, thinking that indeed his time had come. The place in which he found himself seemed to be a huge brick oven, whose circular wall tapered high above him into a narrow chimney and around him some sort of trial seemed to be taking place by torchlight. He was lying propped up by huge bolsters of sackcloth, which smelt most strongly of hops. Indeed, had he but known it, Lord Cullingford was in an oast-house and watching, what many a man would have given his eyes to see, a trial of miscreants conducted by the Scarecrow. Upon two of the prisoners sentence was being passed, and when his lordship recovered his senses the voice of the Archfiend was delivering the verdict and pronouncing punishment.

‘Having found you both guilty of systematically defrauding the fellowship of Romney Marsh by false figures in your account, thereby cheating your comrades, we sentence you to be deported as the Scarecrow shall think fit, the length of time depending upon your future behaviour. Remove them.’ The next offence was of a more serious nature, and the Judge’s voice took on a tone of cold contempt as he described to the full circle of hooded figures a crime of treachery and asked for their verdict, of which there was no doubt, for the ghostly jury, though silent, stretched out their right hands, thumbs pointing down.

The awesome figure of the Judge inclined his masked head as he uttered the dread word. ‘Death, and the manner of it will be ignominious. By promising to betray our whereabouts to the Revenue, thereby hoping by your treachery to gain the Government reward, your body will be found tomorrow morning hanging from the public gibbet, where you hoped by your vile deed to place us. Remove him.’ And the terrified prisoner, screaming for mercy, was gagged and dragged away.

By this time Lord Cullingford was well aware that he was not in Hell, but in the power of the notorious Scarecrow, whom he had so gaily set out to track. Indeed, upon realizing how closely his crime tallied with the last prisoner’s, he had to admit to himself that he was extremely frightened, and when upon receiving orders to take his stand before the Judge, and being helped to his feet by two Nightriders, he found that his legs would hardly support him. Was this to be the end of his wasted life? And upon that moment he wished he could have had a chance to redeem himself, a he had planned to do when riding with the Dragoons. Perhaps this was his chance. He could at least die bravely; and it was thus when Lord Cullingford was steeling himself to hear the fatal verdict that the figures of the Nightriders filed down the stairway of the oast-house and melted away into the night. Only two remained, and these, supporting him, as sick from his fall, and exceedingly weary, though feeling more the man than he had ever done before, he faced the Scarecrow, who demanded, in somewhat softer tones, ‘And what fate are you expecting, my Lord Cullingford?’

Surprised at the use of his name by this uncanny creature, his lordship replied bravely: ‘If it is to be the same as the unfortunate creature that I saw removed, then I ask but one thing – that it shall be swift.’

Which remark appeared to please the implacable figure before him, though it answered sternly enough: ‘That creature was unfortunate indeed. He had committed the crime for which there is no pardon. What then should be the punishment for one who has not played the traitor to us, but to himself?’

Lord Cullingford was silent. Who then was this judge who not only knew his name but also his inmost thoughts? The voice went on: ‘You have seen justice done tonight to traitors of our cause. Your punishment shall be to see that you do justice to yourself. And this may help you to it,’ and he handed to the mystified young man his I O U to Foulkes. ‘This may remove the necessity of your trying to remove me and claim the Government reward of a thousand guineas. I see the sum tallies. As to this Bully – Foulkes. He is our common enemy, for I do not allow wagers of his kind to be pardoned as I am pardoning you. Destroy that paper as I shall destroy the man to whom it’s due.’ The young man thought he must be dreaming, and indeed, before he had time to stammer out his thanks, the strange figure seemed to vanish before his tired eyes. Faint with fatigue and emotion, he knew no more until he woke with the dawn breaking, to find himself outside the Ship Inn. And yet it was not a dream, for there, clutched in his hand, was the I O U. And so as the rim of the sun came over the sea, Lord Cullingford, seated upon the sea-wall, pondered that though he had lost a good night’s sleep he had gained his self-respect.

Chapter 7

Concerning Various Happenings and in which Aunt Agatha Hears a Different Tune

Fashionable London would have been exceedingly surprised had it been able to see what was going on in the kitchen of the Ship Inn at Dymchurch at half past seven in the morning of November the thirteenth; for my Lord Cullingford was breakfasting in a style unheard of in polite society. Seated at the far end of the long, scrubbed table, he was doing full justice to an enormous plate of sizzling bacon and crisp fried eggs, while a thick chunk of farm-house bread, lavishly spread with creamy butter, rested against a foaming tankard. His immediate neighbours were a boot-boy and a comely chambermaid, while grouped round the table were various members of the Ship Inn Staff – some serving-wenches, an ostler, two milkmaids and a cowman, all presided over by an apple-faced cook. The reason for this unorthodox behaviour being that his lordship, having sat for some time on the sea-wall and watched to his great satisfaction the tiny pieces of paper that had comprised the I O U vanish with the receding tide, had become a trifle chilled. He was also not a little tired and very hungry, so finding the front door of the inn still on the chain, he had wandered round through the coach yard in the hopes of seeing someone who might let him in. A most appetizing smell of frying breakfast emboldened him to look through an open window, which caused the aforesaid gathering to rise from their places and stand awkwardly gaping at the peevish coxcomb they had served the night before. This morning, however, he might have been a different gentleman, so changed he was, for in a most natural, unaffected manner he asked if he might join them, and suiting the request to the action, he stepped through the window without further ado.

It was about the time when Lord Cullingford was attacking his sixth hunk of bread and butter that Mrs. Honeyballs was walking through the village on the way to her morning work at the Vicarage. Although she had never been out of Dymchurch in her life she had a habit of conveying to any passer-by that she was a complete stranger, greeting each building as though she had never seen it before. And in order that there should be no mistake she would enumerate aloud in great surprise the names of all the shops she passed, and the people that she saw. So if you followed Mrs. Honeyballs along the street you might hear this curious little sing-song catechism. ‘Ah, lovely morning – isn’t it a nice place – there’s the Church, just see the steeple. Quested, the pastry-cook. ’Morning, Mrs. Hargreaves. There’s Missus Phipps. Oh – sweeping out the Bonnet Shop; doesn’t look so well again. Hope it’s not the megrims. Searly, the butcher – see he’s selling oxtails. Mr. Mipps’ Coffin Shop. Wonder who the next’ll be. Mrs. Wooley’s bad again. Now what’s around the corner?’ She knew perfectly well what was round the corner for she had asked and answered that question for the past twenty years, and she was just about to say, ‘Ah, there’s the dear Vicarage. Privilege to work there,’ when the words stuck in her throat, for on rounding the corner she saw something that was not in her itinerary – in fact, this time Mrs. Honeyballs was really surprised – in truth she was terrified – and flinging her apron over her head and hitching up her voluminous petticoats, she ran screaming at the top of her voice for the Vicarage. What Mrs. Honeyballs saw would have surprised anyone – in fact it would have terrified most people, for hanging from the public gibbet, slowly revolving in the morning sun which glistened and on its protruding eyeballs, was the body of a man. A grizzly object indeed to meet on one’s way to work, and a morbid group of horrified villagers were already in the Court House Square gaping from a safe distance, though one or two, bolder than the rest, were attempting to decipher the roughly scrawled warning stuck to the corpse’s chest; while high above their heads, from the fastness of the rookery, the churchyard carrion in grim confabulation cawed out their greedy tocsin. The babblement below grew from spellbound whisperings to loud commotion as the message ran from mouth to mouth.

‘A WARNING TO ALL TRAITORS ON THE MARSH.’ No doubt who wrote it either, for underneath so all could understand, a crude but vivid drawing of a Scarecrow.

It was fortunate for Mrs. Honeyballs that her lifelong study of every nook and cranny in the village stood her in good stead, or hampered by her apron she would most certainly have come to grief. As it was, with the instinct of a homing pigeon she was able to travel thus blindfold at an incredible speed, finally coming to rest outside the Vicarage back door, where she was able to gasp, ‘Thank goodness, here’s the back door – never thought I’d get here,’ as she took the protective covering from her head, and decorously straightened herself before entering the ‘privilege to work there’. Upon entering, however, she promptly bumped into Mr. Mipps, who was coming out, and this sent her into a paroxysm of the trembles.