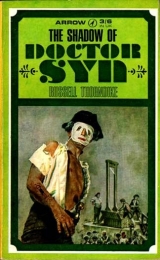

Текст книги "The Shadow of Dr Syn"

Автор книги: Russell Thorndike

Жанр:

Исторические приключения

сообщить о нарушении

Текущая страница: 11 (всего у книги 16 страниц)

1 Flat boards of wood attached to the shoes for crossing the miles of pebbles.

A minute later the Frenchmen heard a door close behind them, and Hellspite lit a lantern from his ‘flasher’ and told the Nightriders who had led them to remove their charges’ masks.

The lantern light showed them a bare room with a groined roof, the only furniture a long table clamped to the floor between the flagstones and two clamped benches. One window higher up in th grey stone wall was shuttered from the outside and barred within.

Decoutier produced a pack of cards and sat down at the table, saying he would play for any stakes till supper should be served, or was it breakfast, he asked – adding that he hoped the fare would be better than the room. ‘’Tis like a room in the Bastille,’ he said.

The Scarecrow had meanwhile ordered the Nightriders to take away the spare masks and cloaks and to bring food. Hellspite slipped after them to hurry things along, while the Scarecrow produced a large bottle of cognac. ‘You shall be host for the moment, Citizen Decoutier. Drink yourself, then see your fellows have some, and do not spare it, for I assure you there is a cellar full to hand.’ He thumped the wall behind him and whispered: ‘And there is such a kitchen on the other side this wall. Fit for a King’s Magistrate, I vow. You’ll have food presently and then perhaps you’ll let me share the dice with you. We must be silent, but that’s no bar to merriment, I hope.’

He tiptoed to the door, listening cautiously. ‘Ah,’ thought Decoutier. ‘He is a careful one, this guide of ours. No wonder Robespierre trusts him.’

The door shut – and then it happened – the awful creeping cold of doubt – followed by the ghastly grip of fear. For all around that table had heard the creaking of a lock shot home.

Chapter 17

A Surprise for Seven Gentlemen

Mr. Mipp was feeling very well that morning. He had had the sort of night he revelled in. Drink, tobacco and the story of his master’s adventure had carried him back to the good old days. He had laughed till his sides ached, he had drunk himself sober, and smoked so many pipefuls that the room resembled a Channel fog by the time they opened the casement to let in the dawn. Indeed, the cosy library of the Vicarage might have been Clegg’s cabine in the Imogene. There was also the added anticipation of seeing the village astounded once more at this latest escapade of the Scarecrow. It so happened that the morning was as foggy outside as it had been in the library; a thick blanket of mist enveloped the Marsh. This called forth the remark from Mr. Mipps that he didn’t know they had smoked so much. Then hurrying along with the Vicar as they went towards the church, this same fog occasioned a slight accident.

Opposite the churchyard wall, not being able to see farther than the tip of his pointed nose, Mr. Mipps inadvertently tripped over something. Like Mrs. Honeyballs, he knew exactly where he was and exactly what he was doing, but he derived great satisfaction in making his planned performances convincing.

In the most aggrieved, innocent tones he was able to muster, he pretended that he had hurt himself, as he hopped delightedly round the Vicar on one leg. ‘Ow, me poor leg! Why, blow me down if I ’aven’t gone and tripped over the stocks. Ought to know where they was by now, oughtn’t I? And knock me up solid, if there ain’t some naughty person in them.’

He peered closer. ‘Why, goodness gracious me, Vicar – it’s the Beadle!’

The Vicar appeared to be astounded. ‘The Beadle, Mr. Mipps?’

‘Now whoever could ’ave put him there?’ said Mipps to the fog. ‘Oh, what a wicked man! He smells of drink.’

At that moment the Beadle opened his eyes and groaned, and between sneezes and moans managed to tell them that he did not know who had put him there, or what had happened to him since he had left the Ship Inn the night before. He protested bitterly and demanded to be released. His head was splitting and he was going to complain to Mrs. Waggetts about her beer.

How to get him out was now the question.

‘Well, you’re the Beadle, ain’t you? Where’s the key?’ asked Mr. Mipps. ‘You ought to know if no one else does.’ He knew perfectly well that the key was in the Beadle’s pocket, where he had put it the night before, but he suggested that the Beadle should look through his own pockets. The Beadle argued that he always carried official keys at his belt, and since he ‘wasn’t no acrobat’ Mr. Mipps had better help him, and sure enough the key was found. Upon being released, the portly Beadle was so stiff and dizzy that Mr. Mipps felt obliged to assist him to the Court House Lodge – telling the Vicar that he wouldn’t be a minute and handing him the keys of the church.

Twenty minutes later Mr. Mipps opened the vestry door and grinned at the Vicar. Then he came in and closed it carefully behind him. ‘All accordin’ to plan, sir,’ he said delightedly. ‘Started off lovely. The Beadle feelin’ a bit guilty like, said he’d better go and see what had ’appened in his absence, though as the cells had been all empty, he wasn’t expectin’ no trouble. Well, down he goes, and he certainly found what he didn’t expect, a whole room full of it. He reads them papers with the Scarecrow’s signature what was pinned on the door, and then there weren’t no stoppin’ him. He dursn’t look in even, though I ’ad a good peep. There they was, all six, sleepin’ like babes, with ever such a surprised look on their faces and that there laudabum-brandy bottle empty beside ’em. I done what you said, told the Beadle not to breathe a word to none, but to report it quick and Bristol fashion to the Squire. But he’s too scared to gossip, sir.’

‘That’s as well, Mipps,’ nodded the Vicar, ‘since we do not wish it to reach the ears of Barsard until we are ready for him.’

At that moment there was a rap upon the vestry door, and a muffled excited whisper: ‘Christopher. I say, Christopher. Are you there?’

Mr. Mipps’s wink to the Vicar plainly said, ‘And now we’re off.’ The door opened and round it peered the bewildered face of the Squire.

‘Good morning, Tony,’ said Doctor Syn. ‘You’re up betimes.’

‘So are you,’ replied the Squire. ‘Beadle told me. Didn’t know you were back. Thank Heaven you are.’

‘I have but now arrived from Rye,’ explained the Vicar. ‘I came by boat; but there, what news I have can wait. I did not think to see you till the birthday festivities tonight.’

‘Festivities!’ snorted the Squire, closing the vestry door and coming to the table at which the Vicar sat. He leant over and said excitedly: ‘It won’t be only birthday festivities we’ll be havin’ when this news reaches London. I say, Christopher – the most astoundin’ thing’s happened. I don’t know what to make of it.’

From his appearance the last remark was obvious for he was in turn both angry and delighted. Dressed in his hunting clothes, he complained that the Scarecrow had spoilt yet another good day’s sport. ‘Though, mind you,’ he said, ‘I’m deucedly grateful to the fellow.’

‘I don’t quite follow you, Tony,’ said Doctor Syn. ‘I should have thought the fog would be the cause of stopping your amusement.’

‘Oh, that’ll clear,’ said Tony. ‘But what the Scarecrow’s done will want a lot of clearing up. In fact, damme, I don’t know how to begin. I suppose I ought to send a messenger hotfoot to Mr. Pitt.’

The Vicar purposely misunderstood. ‘Why, whatever has Miss Agatha’s poodle been up to now?’

‘No, no, I don’t mean that toe-bitin’ little brute. I mean Mr. Pitt. The Mr. Pitt. The Minister of War.’

Then, seeing that Mipps was tactfully about to withdraw, he added: ‘No, my good Mipps. Stay here. I think perhaps that you can help us, and you ain’t the gossipin’ sort…’ At which Mr. Mipps pulled his forelock and thought that it was better to be inside in the warm, even though the vestry had got a nice big key’ole.

The Squire came straight to the point. ‘Now lookee, Christopher. As far as I can see, I’ve got six French spies in my Court House. And damme – I don’t know what to do with ’em.’

‘Well, Tony,’ and the Vicar shook his head, ‘I’ve heard of red snakes and pink elephants early in the morning, but French spies is perhaps the latest fashion —’

‘No – no, I’m perfectly sober – sober as a judge this morning.’

The Vicar smiled. ‘The comparison is questionable, Tony,’ he said.

‘Oh, don’t you Caroline me,’ snapped the Squire. ‘I’m too worried – I tell you, Christopher, I have six of Robespierre’s picked men, and they’re a present from the Scarecrow.’

‘Good gracious me, Tony. Being in the Vestry I am persuaded you are not pulling my leg. Yet I cannot credit it. Six? In the Court House? Present from the Scarecrow? How on earth could they have got there?’

‘Oh, don’t ask me – ask the Beadle.’ (Really, Christopher was being confoundedly stupid this morning. He had hoped for good advice, and here he was making idiotic suggestions about coloured animals. Pink elephants, indeed! He wished the Beadle had seen pink poodles – or been bitten by a white one. What with using his own stocks for a night out and then his excuses about the strength of Mrs. Waggetts’ liquor… The Squire couldn’t think of anything bad enough for him, seeing that he was perfectly sober himself that morning and had therefore no fellow-feeling for a thick head. Apart from all this the Beadle’s terror of the Scarecrow irritated him beyond bearing, since the great fat oaf should represent his own strong arm of the law instead of shaking like a jelly. Now, damme, Christopher was taking the attitude that the whole thing was a parcel of lies!)

‘But how do you know that they are French?’ asked the Vicar. ‘And how do you know that they are spies? You say the Scarecrow sent them to you?’

‘How do I know?’ repeated the Squire. ‘Because I can read,’ and taking from his pocket a number of papers, he slammed them down triumphantly on the vestry table. ‘There you are – read for yourself. They were fastened to the door of the Common Cell. Damn’ fool Beadle wouldn’t take them down. Had to do it myself. My French ain’t good, as you know, but what I can’t speak in their God-forsaken jabber I can just manage to read, and if this don’t prove them six to be as dirty a lot of scoundrels as the man who put his signature to it – that “Robespeer” – then my name ain’t Antony Cobtree. Come, man, read ’em yourself. You’re the scholar here and I want your advice. Don’t you realize, Christopher, that this is a hanging business – not down here, outside my windows, thank God – but at the Tower of London

– and it’s our Scarecrow who’s done it. Damme, I always said the fellow had some good in him. This’ll make him more popular. Lud, Christopher, I don’t know what to do.’

Doctor Syn at last appeared to understand the importance of the situation. ‘I do admit,’ he said, ‘that you are faced with a devilish tricky business. Do you think that this will gain the Scarecrow’s pardon? For much as I disapprove of him, you’re right in saying that he’s struck a blow for England. But they could hardly pardon him unless he pledged his word to cease his illegal trade.’

‘I know what I’d do here,’ cried Tony. ‘I’d use my authority and pardon him out of hand, then call him as chief witness for the Crown. But what those tom fool London judges will do is a very different matter. Now I ask you, Christopher, what in Heaven’s name is the best course for me to take?’

This was the opportunity that Doctor Syn wanted. He told the Squire that in his opinion the whole thing should be kept quiet, and that he, as Chief Magistrate of Romney Marsh, should go to Mr. Pitt and tell him everything. ‘You realize, Tony, that the Scarecrow has done you a service which will reflect much honour on you?’

This the Squire did realize, and agreeing that the matter should be handled for the moment in great secrecy, asked how he could account to the village for the six prisoners in the cells. Doctor Syn’s advice was that he should instruct the Beadle to keep silent on the true facts, and to put about the rumour that they were smugglers caught on the Marsh who were now awaiting legal proceedings. He turned to Mr. Mipps and said with a smile: ‘Although I know it is against your principles to tell untruths, yet since the Squire has been so gracious to allow you to hear this staggering news, I feel sure you will see that the village hears only what they should. You understand?’

‘Oh, yessir,’ replied the Sexton promptly. ‘I don’t like falsehoods, but I don’t mind foxications. Sussex smugglers, you says – Sussex smugglers it is, until such time as the Squire says ’tisn’t and tells ’em what they really is.’

The Squire thanked Mipps for an honest man, but failed to notice the look of complete understanding that passed between the honest gentleman in question and his master.

It was further decided that Major Faunce of the Dragoons should be taken into their confidence, and Mipps was despatched to require his presence immediately with four of his best men in the official rooms of the Court House. So within the hour under military escort and preceded by a slightly confused Beadle, the Chief Magistrate, the Vicar and the Sexton descended to the cells.

On the flagstones in the passage Mips pointed to a pile of weapons – some dozen pistols, three or four cutlasses, and one sword and sheath that that seen better days which Doctor Syn recognized as the dandy’s, lay in a pile by the Common Cell door.

Major Faunce admitted grudgingly that the Scarecrow certainly was thorough, for the prisoners had evidently been disarmed, and that it was as audacious a bit of work as ever he had seen. The sight of these weapons, and the presence of the Dragoons, lent the Beadle sufficient courage to unlock the door. He was still uncertain as to whether he would be punished for his unwitting help in the Scarecrow’s latest exploit. So in order to regain a little self-confidence, he made a deal of official pother in selecting the right key from the vast Government collection at his waist. He directed most of it to Mr. Mipps, his parochial rival, in order to make up for his lack of dignity earlier on.

The great key clanked and turned in the lock, and the heavy door swung open. This noise struck some chord in the fuddled minds of the six prostate men, and slowly six pairs of drugged eyes opened, shut, and opened again. Truth dawned on their stupefied brains. Here was no symbol of the Reign of Terror – Citizen L’Épouvantail, Champion of the Republique and friend of Robespierre, but the calm impersonal strength of English faces, and behind them what was unmistakably the scarlet of military. Standing out from this awe-inspiring group was the tall, spare, black-robed figure of a priest. To them the meaning was clear, the surprise – unpleasant. Six pairs of eyes closed desperately in the vain hope that this was but a dream.

Chapter 18

Aunt Agatha Scares the Scarecrow

She looked back down those years and found that they had not been so lonely after all. She had wanted to give herself to one person, but since this was not to be she had given of herself to many and her reward was great. She had attracted to herself interesting people from all walks of life, and she never lost the love of youth, and therefore kept alive an unfailing instinct for romance. She had sensed this intangible something a few days ago, and felt that very soon both conspirators would seek her out. She was ready for it, and she had a vast knowledge of humanity from which to draw.

Tonight, therefore, she was as excited as if it had been her own romance, and when a gentle tap upon her door broke her reverie, she cringled with anticipation.

Upon her gay invitation, Cicely swept in like a golden cloud, and both ladies regarded each other with approval, exclaiming simultaneously, ‘Lud, how pretty you look.’ At which both burst out laughing at having made the same ordinary remark.

‘For,’ said Cicely, ‘it is the wrong word – you look magnificent,’ which in truth the old lady did.

Her ruffled gown of white and silver brocade, and her high white wig turned her into a Royal figure. Cicely saw that she was wearing her Gordon sash in honour of the occasion, and very little jewellery save for her rings and the dog’s-head brooch.

The old lady stepped back and looked with head on one side at her niece

– Cicely had taken trouble for someone and it had been worth it. The gold of the full dress showed off the warmth of her skin and reflected against the gold lights in her hair. ‘And I vow you look magnificent too, child,’ she smiled back at the radiant girl, noting with satisfaction the eager expectancy in her firm young body and the tender expression in her eyes. Here were the signs she had looked for, and she wondered just how much was going on inside that proud little head, with its sweep of auburn hair and clustered curls.

Cicely smiled back at her and held out the velvet case she carried, saying that she had come in to be shown how to wear the jewels to the best advantage, and would Aunt Agatha put them on for her. She knelt down and the old lady clasped the diamonds round her neck and pinned the stars in her hair. But when it came to ear-rings and brooch Cicely laughingly demurred, with ‘Lud, I dare not wear more, for already Maria is like to scratch my eyes out seeing she’s only wearing Mamma’s second best garnets.’

‘You need no jewels to set you off,’ cried the old lady. ‘And I wonder what gentleman will agree with me on that score. Well nigh all of them, I expect.’ She decided now to tease Cicely. ‘Why there – I knew I had a bit of news. The dear Vicar has returned from Sussex. But of course you will have heard of that already.’

‘Why yes, indeed, ma’am.’ Cicely knew full well what the old Pet was after and determined to surprise her. ‘After our tedious feminine day in Hythe, I was in need of moral support, so I begged Mamma to stop the carriage and let me out, saying that I must walk or run mad. Both foolish creatures told me the wind and spray would play havoc with my hair, and that I should look a fright. But curl or no, I should have run mad had I not seen him before tonight.’ She looked boldly at the old lady and laughed. ‘There, ma’am. Now I’ve said it. Am I not a forward hussy? I saw him at the Vicarage and kissed him too. Oh, tell me what to do, for I shall never love another. And I dare not tell the family, for they do not know him as he really is.’

Cicely had not surprised Aunt Agatha one wit – but she pretended to misunderstand. Which indeed was all in the fun of the game.

‘Your Papa should know him. They were at school together.’

‘Oh, Aunt Agatha, can you imagine dear Papa really knowing anyone? But I suppose ’tis not considered the proper thing to marry one’s father’s college friend.’

‘Fiddlesticks, my love. Pay no attention to what is or what is not considered the thing. You can marry Methuselah if you’re in love with him. Doctor Syn may try to make himself out as old as Methuselah, but he has not succeeded in convincing us, and you are in love with him, aren’t you, my pet?’

Both Cicely and Aunt Agatha knew the answer to that question, but before it could be told there was a knock upon the door and Lisette entered with a message from Lady Caroline to say the dinner guests were all assembled and waiting in the Great Hall for the guest of honour, and Miss Cicely.

The two ladies looked at one another with guilty amusement; then they sped hand in hand along the Gallery towards the head of the stairs. More like two sisters than great-aunt and niece, they laughed gaily as they peeped over the bannisters before descending.

‘I vow we’ve timed our entrance to a nicety,’ whispered Aunt Agatha. ‘Yes, they’re all assembled. I see Maria is doing her best with the Major, garnets or no. Yes – I admit she’s looking well tonight, though I never did care for pink myself. And look at Doctor Syn. Why, nobody could accuse him of being Methuselah now. He looks for all the world like a racehorse waiting to be off. How elegant he is tonight. I never noticed his broad shoulders before. It is because we’re looking down on him no doubt, ’tis tiresome having always to look up. I wish I were as tall as you, child. ’Tis quite delicious keeping them in this suspense.’ The old lady chuckled.

Indeed Doctor Syn was in such suspense that he had quite forgotten to be the parson, and the fact that the old lady was looking down at him did not entirely account for this new vision of his shoulders. For subconsciously he had braced himself to meet this new disturbing element. Standing by the great fire listening with but half an ear to Lady Caroline’s prattle, he caught sight of himself in a long mirror hanging on the opposite wall, and for the first time in many years he almost hated his protective cloth. He wished that he could dress to suit his mood, and his mood being dangerous he would have been better clothed in all Clegg’s daring insolence. He longed to know what these good people would do should he be thus suddenly transformed and appear before them in his scarlet velvet – but above all he wanted her to see him in his swaggering glory, instead of this creeping, churchyard black. He almost cursed himself for his cowardice in not declaring who he was. Then suddenly his mood changed again, and flamboyance leaving him, he felt very small and humble, with but one desire, to run away and hide, lest he should disappoint her after all. Yet this was the man who had but two days before laughed in the face of the Terror and struck cold fear to Robespierre’s heart. And here he stood, all three of him, afraid of one young girl.

Above the chatter round him he became aware of voices and laughter high up in the gallery. He glanced in that direction and then laughed as well, for there they were and he knew what they were doing – peering from the fighting-tops before setting their sails for the attack – like the two naughty pirates that they were. He was no longer afraid, and as they came down the stairs demurely holding each other’s hand, his heart melted. The glorious contrast that they made – the white and silver of the fine old lady and the young girl’s golden warmth against the background of the tapestries – held him enthralled.

Half-way down the stairs Aunt Agatha whispered to Cicely behind her fan: ‘Doctor Syn is looking so handsome now that I vow I shall steal some of your dances with him, for my other two beaux will never attend. Perhaps it is as well, for I never told your dear Mamma that I’d invited them and one could hardly expected poor Tony to approve.’

Cicely whispered back: ‘Then you are the only other woman who shall dance with him tonight. Even so, ma’am, I am not sure that I shall trust you.’ She gave her aunt’s hand a squeeze as they reached the foot of the stairs. The old lady returned it like the arch conspirator she was and then was claimed by the company.

Since this was merely an informal dinner before the main body of the guests arrived, the small dining-room was used, and since it was a family gathering with the exception of his old friend Sir Henry Pembury and Major Faunce, the customary ceremony was dispensed with.

Cicely, sitting between Major Faunce and Sir Henry, wished that the Major would pay more attention to Maria and that old Sir Henry would not tell her so many anecdotes of his young days. Across the table through the branches of the silver candelabra she could see Christopher, neatly dodging her mother’s domestic barbs and concentrating his attention on Aunt Agatha, which lady directed across the table to her favourite niece a wink worthy of Mr. Mipps himself.

With the dismissal of the servants after each course the conversation became easy and natural, and unhampered by necessary caution, since the chief topic was the strange happenings in the cells that morning. Sir Antony was in fine fettle, cock-a-hoop taht he was to ride to London the next morning to visit Mr. Pitt. He became so naughtily pompous that one might have thought he had done the whole thing single-handed. He even so far forgot himself as to round on Doctor Syn and to expound to him the very theory which he himself had laid down that morning. The Vicar could not help laughing when Sir Antony, booming his arguments across the table to Sir Henry, ended up with: ‘Much as I disapprove of him I think I’m right in saying that he has struck here a blow for England.’ Having delivered this piece of borrowed oratory, he infuriated Lady Caroline still further by monopolizing the conversation and the wine, giving vivid descriptions the while of what he would or would not say to Mr. Pitt. In point of fact he knew quite well that when he eventually did see Mr. Pitt he would as usual be completely tongue-tied, so he took this glorious opportunity of airing the views he knew he would forget. He pardoned the Scarecrow a dozen times and then condemned him again, until Sir Henry, also a Justice of the Peace, cried out: ‘But you can’t condemn the rascal, Tony. Don’t you see the Crown must have him for a witness, and ex necessitate rei, if you follow me?’

‘Of course – of course,’ put in Tony, who didn’t at all. ‘Then he must and will be pardoned.’

Here, much to everyone’s astonishment and Aunt Agatha’s delight, the quiet voice of Cicely broke in upon the gentlemen. ‘Has it occurred to any of us that he may not want a pardon? For my part I do not think he does. Nor do I think he will come forward.’

But Major Faunce was inclined to agree with Cicely. ‘Though,’ he said, ‘I have a theory that my brother shares with me, that the Scarecrow is none other than the famous Captain Clegg, believed by some to have been hanged at Rye, and buried in the churchyard here.’

Cicely knew that she dared not move lest she betray herself. Nor did she trust herself to look at Christopher, but sat, her heart contracted in the grip of deadly fear, while Faunce beside her went on doggedly: ‘If this is true then it will be worth his while to stand as witness, for then his pardon would be doubled. But can they do it? Can they pardon a high-seas pirate?’

Sir Antony was emphatic on this point. ‘The Crown can pardon anyone it pleases – but they’ve got to prove he was Clegg and how would you set about that?’

The calculating voice of the soldier answered. ‘Because, me dear sir, the mark of Clegg is on his arm, an old tattoo mark. A picture on his right forearm of a man walking the plank with a shark beneath.’

Here Maria broke in excitedly: ‘But that was the picture on the arm of the man who rescued us from Paris and —’

There was a sudden sharp splintering of crash and Cicely’s glass shattered against the candelabra, spilling its red wine over the table. She was profuse in her apologies, but she had achieved her object, for by the time all was quiet again after the dabbings and the moppings-up, people were wondering what they had been talking about, and started afresh. All but Faunce, who sat silent and stubborn beside her.

Cicely was pale, but the set of her chin was determined and she now looked round as though challenging anyone to reopen the subject. Two people alone noted this and loved her the more. Aunt Agatha and Christopher Syn. But Maria would not be put off, and turning to her sister, continued: ‘You seem to forget what I saw in Hythe this morning, Cicely. I don’t think the Scarecrow is as wonderful as all that, since there is one spy he has not caught.’ Now everyone was all attention to Maria she glanced triumphantly at her sister and went on: ‘I know he is a spy and a very dangerous one, since it was he who forced my poor Jean to do all those terrible things, and then betrayed him. And then you know what happened.’ Here she became tearful and was about to tell Major Faunce how her young foolish husband had been denounced and guillotined when Doctor Syn, as though to change the painful subject, spoke to her across the table. ‘Dear me, I wish I had known you were going into Hythe, Maria, dear child. I would have asked you to do a little errand for me. To call in at Mr. Joyce the saddler for a pair of blinkers that I ordered for my churchyard pony. I fear she is getting beyond my control – she actually unseated me the other day – having caught sight of the Beadle.’ Cicely alone noticed the gleam in his eye and hurriedly looked away for fear of laughing outright. The Squire was about to say that he quite agreed with the pony – but the Vicar continued, ‘But there, I beg your pardon. You were telling us something interesting. What you saw in Hythe, was it not?’

Maria was delighted that the Vicar had for once deigned to notice her, and broke off, without so much as asking the Major’s pardon, to answer him: ‘Oh, dear Doctor Syn, did I not tell you? ’Twas while Mamma and Cicely were in the Bonnet Shop, and I was alone in the carriage, that I saw Monsieur Barsard. I know it was he. But I did not wish him to see me, so I hid and then I watched him through the window after he had passed. So I am quite sure it was the brute. But I don’t really see why you should all be so pleased with the Scarecrow since he has failed to catch the leader of Robespierre’s spies.’

It was at that moment that Lady Caroline, thinking that her daughters had taken too much license in the conversation, and seeing a restive look in Sir Antony’s eye, which meant one thing only – port – rose to her feet, and the other ladies followed suit and accompanied her to the drawing-room.

Aunt Agatha’s eagle eye had not missed any of Cicely’s reactions, and she felt strangely protective towards her now she knew what the girl was faced with. She applauded the deliberate action that Cicely had taken in silencing Maria, and vowed she would not rest until she had probed this disquieting problem further. For what at first had seemed to her the Overture to an ordinary though charming Romance, now took on an almost menacing air and her fey Scots instinct told her that something vital was unfolding before her very eyes.

So she waited opportunity to draw Cicely aside, and taking both her hands in a surprisingly firm grip told her to be of stout heart, and that she was with them whatever might befall. Her Highland home was at their disposal, and, if they had to take the journey hurriedly, why, then, Gretna Green could be taken on the way. From the strong fingers of the little old lady into Cicely’s hands, then through her very veins, there seemed to flow some of the virile fighting spirit of the Gordons, for her chin went up and her eyes lost the haunted look that had clouded them during that period at dinner. She smiled very sweetly, then leant over and kissed her little great-aunt.