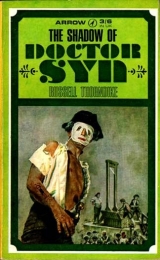

Текст книги "The Shadow of Dr Syn"

Автор книги: Russell Thorndike

Жанр:

Исторические приключения

сообщить о нарушении

Текущая страница: 3 (всего у книги 16 страниц)

And so the conversation rolled on from one topic to another. Doctor Syn had by this time politely insisted upon Lisette taking his more comfortable seat, which though it infuriated the Captain, placed him in a better position for conversing with the old lady.

By the time the coach had reached Canterbury, their talk had brought them to the most popular topic of the day – occasioned by Doctor Syn remarking the little grotesque black patch upon Miss Gordon’s cheek – the topic which was inevitable at any fashionable gathering – namely, the Scarecrow, whose exploits amused the old lady vastly, though Lisette, frightened out of her well-trained servility, showed signs of apprehension at every mention of the name, till the old lady rated her for being a superstitious fool, and told her not to listen.

The Captain, on the other hand, appeared to come to life for the first time on the journey and listened to every word with avid attention, though neither he nor the old lady noticed the gleam of amusement that lurked behind the parson’s spectacles, as he spoke to the Captain.

‘I trust, sir, you will forgive a comparative stranger for addressing you, but you will understand from our conversation that our Marshes are not considered healthy at the moment. Indeed, Dymchurch-under-the-Wall is not as fashionable as Brighton.’ Then with an admirable piece of play-acting he pretended to recognise the Captain for the first time, exclaiming: ‘Dear me – your face is familiar. Have we not met before?’

To which the Captain was forced to reply: ‘Yes, sir. Last night – in Crockford’s.’

‘Yes, indeed, of course – the wager. Had you but spoken sooner, I would have recognised your voice. Pray forgive me. My eyesight, you know. At Crockford’s, yes. Foolish of me to think you were coming to Dymchurch for your health.’

Although to the ladies the words conveyed precisely what they meant, the Captain had that same uncomfortable feeling at the pit of his stomach that he had experienced earlier in the day.

Doctor Syn, turning to Miss Gordon, added: ‘May I present, ma’am, a very famous English gentleman, and indeed a brave one, for he has wagered two thousand guineas that he will catch our Scarecrow within the week. Captain Foulkes – Miss Gordon.’

Miss Gordon gave the Captain a curt nod and did not seem very impressed, though Lisette was obviously gratified that she was riding in the same coach with a fine gentleman who was about to destroy the chief cause of her worries.

And so, on through the busy narrow streets of Canterbury, with the coach-horn playing a merry tune which caused Miss Gordon to exclaim: ‘Sakes alive, is that the only tune he can blow? Have you noticed he has played nothing else the whole journey?’

To which Doctor Syn replied with a smile: ‘You have a musical ear, madame. ’Tis the “British Grenadiers” is it not? In honour, no doubt, of our noble Captain here.’

‘Oh, I know the tune,’ replied Miss Gordon. But what she did not know was that the honour was due to the Scarecrow, who by this ingenious method told his followers throughout the countryside of his activities, each tune played meaning a different order. Had the guard been of a communicative disposition he could have told the occupants that in Scarecrow’s music, the ‘British Grenadiers’ meant ‘A false run tonight to lead the Revenue astray.’

Pulling up at the ‘George and Dragon’ for a final change of horses and half an hour’s rest, they started off again to the strains of the same enlightening tune, past the Cathedral and shops and on into Stone Street with its long stretch of straightforward road, lying open and innocent save for the lurking farm-house, and the coppice which had served its purpose earlier that morning. A good run until the southern end – the dread of every driver – Quarry Hill. Here the coach had to be stopped for skids, and then slowly down the winding gorge, which was overhung so heavily with giant foliage that even in the strongest sunlight it was like passing through an endless tunnel.

So went our coach – the horses straining back, the coachman leading them and the occupants forced to cling to their straps, as the vehicle lurched on its tortuous way down the hill.

‘Might be in the Highlands,’ exclaimed Miss Gordon.

‘Yes indeed,’ replied Doctor Syn. ‘’Tis precipitous as the stretch which we have just left is straight. You must blame the Romans if there is any blame for such a lasting road. The hill takes its name from the quarry which they used to work, transporting the stone for the building of Canterbury. Though we may not like to admit having been conquered, we must yet thank the Romans for much. Indeed there cannot be a man o’ Kent on our coast who does not sing their praises for the ingenious construction of Dymchurch seawall – a magnificent piece of engineering. Otherwise the seas would still be lapping against the hills behind the Marsh.’

‘There, Lisette, what did I tell you?’ cried the delighted old lady. ‘Though the sea is higher than the land, you will not get your feet wet.’ The maid, at last understanding the significance of the wall at Marsh, was loud in her praise of those ancient builders. And so on down the hill, their voices echoing against the steep wooded sides of the gorge, the Captain uncomfortably tilted back, and being exceedingly bored at this archaeological lecture, cried, ‘Confound the Romans, say I. I would they had made this road straighter, and I fail to see why we should overpraise them. For my part, I have no wish to render unto Caesar praise or anything else…’

‘No, my fine gentleman, but you’ll have to render a lot more than praise to Gentleman James,’ rang out a strong voice.

Our friend, the highwayman, had timed his attack to a nicety. The coach had stopped at the bottom of the hill, and both coachman and guard were busy removing the skid chains, the latter having most carelessly left his loaded blunderbuss upon the roof of the coach. Both men, taken by surprise, and powerless to assist, took cover behind the huge wheels, while a gay masked face and two horse-pistols menaced the confused passengers. The terrified Lisette, thinking the apparition none other than the Scarecrow, broke into her native tongue and mingled with the Captain’s oaths and Mister Pitt’s excitement; the voices of the little old lady and Doctor Syn were hardly heard at all.

‘Come now,’ cried Mr. Bone, enjoying the joke hugely, ‘who will be the first to render unto Jimmie Bone? Oh no, Captain, I shouldn’t try and touch your sword. This is my territory – not your St. Martin’s Fields.’ And that angry gentleman, whose fingers indeed had been twitching at his hilt, was flummoxed into silence. ‘Ladies first, sir, I’ll relieve you of that later,’ continued Mr. Bone. ‘Come, miss, the guard will assist you to descend.’ The trembling maid, clutching the jewel-case, was helped out of the coach while Mr. Bone emptied the jewel-case into his saddle-bag. Lisette, having no personal effects, was allowed back into the coach, and Miss Gordon was the next to descend, which she did, all outward indignation, though secretly enjoying the adventure. Taking the rings from her plump little fingers, she advanced fearlessly to Mr. Bone and handed them to him. He had to stoop low in the saddle to take them from her and he said, ‘’Tis a crying shame to take the rings from such a pretty hand.’

‘I have no wish to cry, and no compliments, please,’ she snapped. ‘I am too old for jewellery, as anyone can see, but ’tis most annoying of you, sir, or rather ’twill annoy my niece Cicely Cobtree, for I had planned to leave them to her. And shall have something to say to her father if he can’t keep order on his own land better than this.’ So saying, the old lady handed over the rest of her baubles, and called to the poodle, ‘Come, Mister Pitt, give the gentleman your bracelets.’ Thus summoned as he thought for another perambulation, the white poodle took a happy flying leap through the open door and pranced, jingling, round the hooves of Mr. Bone’s horse, which said gentleman was so amused and having taken a liking to the courageous old lady, swept off his hat and laughed. ‘Though I have robbed many a dirty dog, ma’am, I have no wish to rob a clean one, and with such a famous name to boot.’ So Mister Pitt, with property intact, followed his mistress back into the coach, and Jimmie Bone peered inside to select his next victim.

Upon seeing Doctor Syn he seemed to be most annoyed. ‘Devil take it!’ he cried. ‘A parson, and I must live up to my old slogan and respect the cloth. I never robbed a cleric yet, though I once had the Archbishop himself in my power, and I don’t doubt that the old Agger-bagger hadn’t more in his bags than you, eh, Mr. Clergyman?’ And had anyone been able to see beneath Mr. Bone’s mask they might have been surprised to see him give Doctor Syn a gigantic wink.

So there was nothing else for the Captain to do than to scramble ignominiously out on to the road, while Jimmie Bone surveyed him critically, and said: ‘Well, here’s a fine gentleman, and with a fine reputation too if I’m not mistaken. I warrant you’ll be visiting the coast for the good of your health.’ Again, the warning note. ‘Then you’ll not be needing the sword that’s hanging by your side. Come, sir, hand it over. Oh no, sir, sheath and all. You might be tempted else to pick one of your customary quarrels with some poor Kentish lad.’

And the glowering Captain could do nought else hand over his infamous duelling-sword. After which he was made to turn out his pockets while the guard was ordered to go through the mail bags and luggage. So it was that when the Captain was finally prodded back into the coach by the tip of his own sword, he had very little left other than what he stood up in, his stock-intrade, guineas for gambling, and weapons for killing gone, as were his beautiful Hessian boots.

And so it was with bulging saddle-bags and full pockets that Mr. Bone bade them a cheery farewell, and putting his horse to the bank, rode up it and vanished in the dark seclusion of the woods.

The person who seemed least affected by this untoward adventure was Miss Gordon, who, although she had lost a considerable amount of valuables, could hardly retain her laughter at the Captain’s discomfiture, as he sat, a sorry sight, in his stockinged feet. Indeed she had to hold her muff to her face to hide her uncharitable amusement. Doctor Syn may have noticed this, for hie was the first to break the silence, by addressing the Captain. ‘My dear sir,’ he said, ‘this rascal has left you in a deplorable state. Indeed you must be regretting already your resolve to visit our part of the country. For my part, I cannot apologise enough, for I should have included highwaymen in my list of dangers that you might encounter on the Marsh. Now, we must see what can be done. It is my duty to assist you. Your feet. Dear me. Now – I have a pair of carpet-slippers in my bag – perhaps you would – you couldn’t? No? Oh well, perhaps you’re right. A village cobbler, perhaps. Then please let me lend you a guinea or so, until you find yourself in funds? Oh, in insist,’ and the Captain had the mortification of having to accept Doctor Syn’s offer. He also had a nasty feeling that the parson was laughing at him, so that he was further piqued when this ambiguous gentleman continued solicitously, ‘And your sword, sir. Your favourite weapon. Dear me, what a loss. Now, if you will permit me? I have a very fine collection of Toledo blades. I used to fancy myself somewhat as a swordsman – in my younger days, of course. You have only to call at the Vicarage and make your choice of weapons. Can I advise you further?’

‘I can,’ laughingly broke in Miss Agatha Gordon. ‘My further advice would be – when next you go a-coaching, you should disguise yourself either as a parson or a poodle.’

At the ‘Red Lion’ in Hythe, the Dymchurch passengers left the coach, where Miss Gordon was met by a smart turn-out with postilions, the Cobtree arms upon the panelling, so that Doctor Syn, who had intended to take a local coach, was prevailed upon to join her. Luggage piled in, they caught a final glimpse of Captain Foulkes surrounded by laughing postboys and a crowd of gaping yokels, who, having heard from the guard that the robbery had been so neatly done by the popular Jimmie Bone, laughed the louder as the Captain’s stockings picked their way gingerly and painfully across the cobbles to the doubtful seclusion of the bar parlour. With no weapons with which to force his will, he looked as he felt, a bedraggled shadow of his former self. Indeed, the Captain’s courage had vanished with his boots.

Chapter 4

The British Grenadiers

Midway between Hythe and Dymchurch the marsh road joins the seawall and then for three miles runs parallel but beneath it, thus sheltering the traveller from the full force of the sea breeze, for indeed in rough weather it was well night impossible for pedestrians to walk upright upon the footpath that ran along the top of this great stone and grassy bank, though on this autumn evening the weather was calm enough. Dust was falling and the postilions spurred hard to reach home before lantern light, so the smart little chaise sped along the dyke-bound road in fine style.

The comfort of the well-sprung vehicle and the absence of their ill-mannered companion put them in a merry mood, and Miss Gordon, her face no longer hidden by her muff, was able to join Doctor Syn in a hearty laugh when they discussed Captain Foulkes’s misfortune.

‘I vow I would not have cared a fig for his feelings had that roguish highwayman deprived him of his breeches too, for I have seldom met with such a boorish oaf,’ she chuckled.

Which latter thought had already occurred to Doctor Syn with satisfaction, for he had other matters to see to before being able to give his undivided attention to the Captain. This notion, however, he did not convey to Miss Agatha Gordon.

The journey, though short, was also not without interruption, for at a lonely farm-house the postilions, having already apprised Miss Gordon of the fact, stopped to deliver a package that had come down with the mail. This being done, the old tenant came out to pay his respects to the Cobtree chaise, and was delighted to find that the Vicar of Dymchurch was in it. With much bobbings and pullings of forelock, he was presented to Miss Gordon as one of Sir Antony’s worthy tenants. It was during the ensuing catechism put to him by the old lady that Doctor Syn, absent-mindedly, no doubt, fell to humming a gay little tune, which the old farmer, strangely enough, for he was rather deaf, seemed to have caught, for after is respectful leavetaking he went singing lustily through the farmyard, ‘some talks of Hal-ex-ha-han-der, hof the British Gren-ha-ha-ha-dears.’

Though he may have taken some liberties with the original text, he most certainly conveyed the meaning of the song itself, for the catchy tune was caught up by half a dozen labourers working round the farm, and even a fat milkmaid some three fields ahead of the chaise was singing it and marking time in rhythm as she pulled. Indeed, fast as the chaise sped on towards the village, the tune preceded it all the way, till Miss Gordon exclaimed, ‘That teasing tune again. And this time the fault is yours, Doctor Syn, for being quit of the guard we had escaped it, till you started up the plaguey thing again.’

To which Doctor Syn, pleading ignorance that he had hummed the tune, apologised profusely and offered to make amends with a little Handel on the harpsichord at the Cobtrees’ next musical. But upon entering Dymchurch, he could not deny but that the village was ringing with it. Workers returning from the fields, dyke-cleaners swinging their trugs, the blacksmith at his forge, housewives closing shutters, fishermen mending their net and a host of small children running this way and that, all singing, whistling, moving to the selfsame tune; while Mr. Mipps, the sexton, was executing on the churchyard wall as neat a hornpipe as Miss Gordon had ever seen in her native Highlands, and in a voice that seemed to have been tuned and broken at the capstan bar, sang loud enough to let the Frenchies know on t’other side of the Channel the full glories of the British Grenadiers.

At the corner of the churchyard wall upon which Mr. Mipps was thus disporting himself, the postilion, on Doctor Syn’s request, pulled up, and the Sexton, recognising with obvious pleasure his beloved master, finished his dance with an intricate twiddle and with surprising agility leapt down to the road before Doctor Syn had stepped on to it. Shouldering the valise, he stood waiting while the Vicar was taking his leave. He hovered happily, his impertinent ferrety face wreathed in seraphic smiles, and his strained black hair, twisted and bound into a tarred queue, resembled a jigger-gaff, though at this moment it quivered with expectancy reminiscent of a pleased puppy about to wag its tail. His wiry little body suggested more the sailor than the Sexton, and his clothes certainly had something of a nautical air. The villagers regarded Mr. Mipps as a person of importance with whom one could not take a liberty, for it was rumoured that being press-ganged into the Navy he had been captured by the famous pirate Clegg and had had to serve him as ship’s carpenter. Maybe there were some who had their own opinions on the subject, but they would not have dared to voice them, least of all to Mr. Mipps, who, as Parish Clerk, Sexton and Undertaker, was admired and respected. He was the Vicar’s general factotum, though some had their suspicions regarding his other activities. In fact, many a Revenue man worsted by the Scarecrow and his gang was ready to swear that when Mr. Mipps wore that look of injured innocence he had in all probability been up to a bit of no good, and indeed knew more about this plaguey smuggling than he cared to admit. But they never seemed able to put their finger on it, and Mr. Mipps, conscious of his own importance, continued to bask in the reflected glory of his well-loved master.

Before taking farewell of Miss Gordon, Doctor Syn begged her to convey his felicitations to the Cobtrees and excusing himself for not accompanying her on the grounds of their family reunion, promised to visit them on the morrow. With a pat on Mister Pitt’s head, and counselling Lisette not to lose sleep over the Scarecrow, he irrevocably won the old lady’s heart by kissing her hand. Then with a bow he joined the waiting Mipps, and the chaise went on to the Court House.

Mr. Mipps, trotting to keep up with the Vicar’s long, easy strides, became as voluble as he had previously been silent, and embarked upon a long series of questions, answers, happenings, and more questions till Doctor Syn advised him to postpone verbosity as they had the evening before them, adding with an enthusiasm that might have seemed strange to an outsider, that for his part his immediate ambitions centred around a long, strong drink.

‘Well, we know where the best brandy is in Dymchurch, sir,’ suggested Mr. Mipps, as they entered the Vicarage. Panelled in ivory white, the room was of exquisite proportions. Indeed it had been specially designed and personally supervised by Doctor Syn’s friend, the great Robert Adam himself. The fireplace had a dignified mantel with bookcases in pillared alcoves on either side. A log fire burned brightly in the hearth, and the Vicar warmed himself in front of it while Mipps got bottle and glasses. Doctor Syn was glad to be home. He loved his parish and he loved his house, and he stood, glass in hand, appreciating his own taste both for fine old brandy and good furnishings. He watched Mr. Mipps lighting the huge candelabras that stood on the refectory table, and as each candle came to life some aspect of the room pleased him more. The great staircase with its sweep of fluted banisters curving into the room. The deep bow windows with diamond panes, through which twinkled innumerable lights from fishing-boats already putting out to sea, while a great painted globe of the world stood, shining and inviting, in its brass stand as if enticing him to leave home waters and once again put out for distant seas.

For one exhilarating moment he allowed his mind to cover those vast oceans which he knew so well, smiling at some remembered escapade. Strange that this Mipps, his close companion and lieutenant in those tempestuous days, should now be with him in this haven of rest, decorously lighting the candles. It was not often that he permitted himself the luxury of allowing his mind to cram on canvas and to carry him back to the enchantment of spiced islands in the tropic seas, or the heady dangers of blustering broadsides in some open fight.

But Doctor Syn was in a reflective mood – the outcome of his activities during the past week, with which he was fully satisfied. Yet when he pondered over the accomplishment of his latest enterprise he was fully aware that this had but started the overture to a new drama in his life. While his seafaring instinct had always told him, ‘No petticoats aboard’, yet, at this very moment, having stifled the sailor in him to become the parson once more, he realised upon looking round his pleasant home that it did, in very truth, lack that one thing. So it was with an almost imperceptible sigh that he dismissed the future with the past, and brought back his vagabond thoughts to the present.

‘Well, Mipps, is all according to plan tonight?’

‘Yessir,’ replied the Sexton, blowing out the taper. ‘Three cries of the curlew it is, and the “British Grenadiers”. No, I’m not anticipatin’ any trouble tonight – though since you’ve been away, sir, we’ve been sent a bran’ new box of soldiers, as pretty a troop of Dragoons as you ever did see, and who do you think is in command?’

‘I haven’t the faintest idea, Mipps.’

‘No, thought you wouldn’t, sir, so I’ll save time by telling you,’ said Mipps. ‘Major Faunce.’

Doctor Syn received this intelligence with a raised eyebrow of surprise. ‘Never the charming fellow who served with Colonel Troubridge here?’

‘No, not the charming fellow who served with Colonel Troubridge here,’ echoed Mipps. ‘His younger brother, and as like him all them years ago as two peas in a pod.’

‘Well, well, that’s very interesting,’ nodded the Vicar. ‘We must endeavour to entertain Major Secundus, as we did Major Primus.’

‘No, no, sir,’ protested Mipps. ‘Faunce is the name, sir.’

‘Yes, Mr. Mipps, I stand corrected,’ smiled the Vicar. ‘My mind seems to be playing truant tonight and at that moment I was back in the Lower Third at Canterbury School.’

To which Mipps, slightly mystified, replied, ‘Oh well, of course if you’re going back to your second childhood, p’raps you’d like me to fetch you a nice hot glass of milk before tellin’ you the rest of the news!’

‘Well then,’ continued Mipps, ‘item number two. There’s a new Revenue Officer come to Sandgate, and he’s been nosin’ round here too, though I ain’t expectin’ much trouble from him neither, for all they say he’s smart as paint. We’ll soon blister it, eh, Captain?’

‘Mr. Mipps’ – warned the Vicar.

‘Oh, sorry, sir. Quite forgot – eh, Vicar. Wants to see you alone. I don’t do. Leastways I didn’t, so he said. Still, he’ll soon know who does and who doesn’t round ’ere. But knock me up solid, I’d forgotten all about that there Kitty-run-the-street.’1

‘I beg your pardon, Mr. Mipps. And what might that mean?’

1 Marsh term for the common heartsease or pansy.

‘Well, sir,’ explained the Sexton, ‘someone else come nosin’ round ’ere today and wants to see you most particular. I shushed him off but back he come. Wouldn’t go away. Said he’d wait. Sat there. Missus ’Oneyballs had to dust round him. Ever such a ernful1 young gentleman he was. Look like Will-Jill to me.’

‘Mr. Mipps, would you do me the favour of speaking in plain English?’

‘Sorry, sir. Forgot I was talking to the Lower Third. Well, since you’re so judgmatical,2 ’alf past two, it was, to be exact. As fine a young dandy as ever you did see comes prancin’ up the path. I ’appen to be puttin’ a nice bit of manure into the rose-beds at the time, and not wantin’ to be disturbed, I nips into the tool’ouse, and lets Missus ’Oneyballs deal with ’im, but, blow me down, if she don’t come and find me. I give her a talkin’ to, but she says I’d better come and keep a weather eye on him, ’cos she wasn’t goin’ to be left alone with him, not with ’Oneyballs workin’ two miles away. So in I goes, and there he be. And that’s what I told you, see?’

‘Yes, Mr. Mipps,’ nodded the Vicar, ‘you have done full justice to your powers of observation. I gather from your graphic tale that someone has been here who wished to see me.’

‘Right, sir. You’ve got it, sir. First shot, sir.’ Mr. Mipps was delighted as he added, ‘And what a one you was for layin’ a gun, sir.’

‘Mr. Mipps,’ warned the Vicar again, then asked: ‘And what did you do with the young dandy?’

‘Do with him? Nothin’ I could do with him till he get so ’ungry that he stopped titherin’3 about and went back to the “Ship” to get somethin’ to take the sad look off his face. Leastways I ’opes it do, if he’s goin’ to come ’ere again, which he said he would, first thing tomorrow mornin’. Oh, blow me down, give me his card he did. Now where did I put it? Oh yes – ’ere.’ And out of the depths of his capacious pocket he produced an assortment of queer objects. Spigots for barrels, bits of tarred string, measurements for coffins, a twist of tobacco, and amongst all these slightly bedaubed with fish manure, was a card that he triumphantly handed to Doctor Syn. Which said gentleman was not at all surprised when holding the delicate piece of paste-board that had lost its elegance since morning, to find that the name engraved on it was Clarence, Viscount Cullingford.

‘Clarence,’ snorted Mr. Mipps as the Vicar read the name aloud. ‘Silly sort o’ name for a silly sort o’…’ Mr. Mipps did not finish the sentence, but added, ‘Don’t bother your ’ead about who he is or what he wants. I’ll flip

1 Mournful.

2 Critical.

3 Tither about, to waste time, to dawdle.

36 round to the “Ship” and soon get charted up on him.’ But he took care not to mention that he had already slipped there and gained several drinks from the gentleman in question.

‘You need not trouble, Mr. Mipps. I have him spotted. Well, what else? Nothing to report from the Court House?’

‘Coo – I should say there be and well you knows it. The ’ullabelaybaloo started as soon as you’d gone. I ’ave ’ad Sir Antony round ’ere every day with his face as long as a yardarm askin’ for you. Got tired o’ sayin’ you’d gone preachin’ in London. He finally writes a note which he says I’m to give you the first minute you gets back.’

‘Well, I’ve been here more than a minute, Mr. Mipps.’

‘That’s right. So you ’as and ’ere it is.’ And from the desk, Mipps handed Doctor Syn a letter which read as follows:

Nov. 12th, 1794

The Court House,

Dymchurch-under-the-Wall,

Kent.

My Dear Christopher,

Not knowing your whereabouts in London I have been pestering the good Mipps for knowledge of your return. Will you send word of your arrival, for I find myself in need of your counsel. In fact, my dear Christopher, I am confoundedly worried, the reason being that Cicely, ever wayward, has vanished into thin air. She rode off saying that she had a mind to visit the Pemburys at Lympne, but we now find that she never went there, and not a sign have we had from the naughty miss since. Caroline is in a pretty pet as her Aunt Agatha is due here for a visit, and she wanted our girl to make a good impression. I know you cannot fully appreciate the trials and tribulations of a family man, nor understand my mortification when Caroline looks at me as though it were my fault. So do be a good fellow and come and help me out. Yours affect.,

Tony.

Which appeal from an obviously harassed paterfamilias caused the Vicar no astonishment. He almost appeared to have been expecting it. Nor did he show the least surprise on hearing outside the window footsteps crunching the shingle and someone whistling quietly the opening bars of ‘The British Grenadiers’.

Chapter 5

Mr. Bone Whistles the Same Tune

Mr. Bone stepped into the Vicarage and greeted Doctor Syn with the easy familiarity of an old friend. He was invited to divest himself of his riding-coat and partake of the best brandy in Dymchurch, which he did with obvious appreciation, standing with his back to the fire while the Vicar sat comfortably in the corner of the settle. The brightly burning logs and the candles in their sconces over the mantelpiece reflected upon the lofty moulded ceiling the shadow of the highwayman, whose giant frame dwarfed the hovering Mipps as he tithered about the room, filling churchwardens from the generous pot of Virginian tobacco, and keeping the glasses, his own included, up to the brim. His inquisitive nose and the quivering tarred queue behind that balanced it made him look more foxy than ever as he chuckled with delight at Doctor Syn’s account of the journey by coach, of Foulkes’s discomfiture, and the bravery of the little old lady with quaint manner and an even quainter dog; which same old lady in the Cobtrees’ best spare bedroom was now, with the help of Lisette, changing into evening finery. If the gentlemen at the Vicarage considered her manner quaint, they might have considered her language to be more so when she was reminded by her empty jewel-case that Gentleman James had not left her a single bauble. In fact she rated him so fiercely that had Gentleman James but heard her he might have considered her no lady. The old lady was well-nigh forced to borrow her dog’s bracelets. How surprised she would have been then had she known that at that very moment the fate of her missing jewelry was being discussed by none other than the learned pleasant gentleman with whom she had travelled and the robber himself, and this but a stone’s-throw away at the Vicarage.