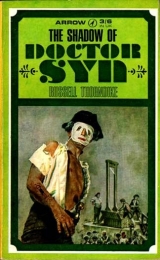

Текст книги "The Shadow of Dr Syn"

Автор книги: Russell Thorndike

Жанр:

Исторические приключения

сообщить о нарушении

Текущая страница: 2 (всего у книги 16 страниц)

‘If I am to carry this thing through, then I must be well armed,’ he thought. He selected a fine pair of duelling-pistols and the holsters, which he must fix to his saddle. He buckled on his sword and, feeling braver under the weight of so much metal, he made his way to the stables, thanking heaven that at least the family groom had remained faithful and that his last and favourite mount would be well groomed and ready for him. He was right. The old man was there, hissing through his teeth and rubbing his hands together in the brisk morning air, but on seeing his lordship he quickly led the mare into the yard. A beautiful animal, in fine condition. ‘She has had a good feed, milord,’ said old Peters as Cullingford mounted.

‘Which is more than I have,’ thought his young lordship, and in a fit of sad generosity he handed the faithful old groom a couple of golden guineas; and so, looking a finer figure than he felt, he rode into the London streets, joining the early cavalcade of carts as they wended their way towards Covent Garden. This annoyed him, for he wished to be quit of London before any of his acquaintances should be about and recognise him, and he did not want his slightly suspicious departure to get to the ears of his one-time patron. So, somewhat delayed, and more than a little hungry, Lord Cullingford crossed London Bridge a mile or so behind Gentleman James.

Captain Foulkes was not in a good humour when he awoke. He had a damnable headache, and his servants were late in calling him, so that he had to hasten with his breakfast and even his meticulous barber cut him most abominably. This, added to the rush and bustle in the Captain’s chambers, made his throbbing head the worse, for there is nothing more irritating to any gentleman who has wined unwisely the night before than to be precipitated into an enforced activity, and indeed the necessity to hasten. In fact, the Captain had a thick head and, in Marsh language, was in a ‘pretty dobbin’.1

1 Temper.

Cravats were flung about as he attempted to get one to set to his liking, and as each attempt meant a fresh cravat, his valets came in for a deal of abuse. And then, to make matters worse, the shaking hand of one of them spilt the boiling chocolate down the Captain’s best white buck-skins. Yet all this commotion in the Captain’s dressing-room was as nothing to the turmoil in the Captain’s head. The events of the previous night had not alleviated the irritation which he realised had started during his unsatisfactory passage of words with that confounded parson at Crockford’s, for the Captain was more than aware that he had come off worse in that encounter, and there was nothing he hated more than being made to look foolish in the eyes of his fashionable followers. There had been no man living as yet who had got the better of him. It was, therefore, most galling to have been so verbally pricked by a clergyman against whom there was no retaliation. Bad enough to have been soundly slapped in the face, not only morally but actually, by the beautiful Harriet, who had proved not so docile, in spite of his boastings. ‘Confound all women and parsons too. They should not be permitted to trade on social protection,’ for the Captain had to admit to himself that his visit to the lady in question had not been a success. Having left Crockford’s and made his way to her apartments on the farther side of the Park, it was most irritating, therefore, to be kept waiting on his arrival, and then, when she did deign to appear, instead of a creature all smiles and caresses, eager to please and charm him, which might have somewhat cured his irritability, he was met, in truth, by a virago, demanding already to know why her salon had not been visited that night, and he had the greatest difficulty in explaining to her the reason of his wager. The scene was stormy, and instead of applauding him as a brave man, and the hero he wished to appear, she soundly rated him upon the fact that for the next few days her life was to be so dull. Then in the way of all women, being thoroughly inconsistent, she vowed that his proposed journey had nothing whatever to do with the Scarecrow, but that, tiring of her, he had elected to go chasing some Kentish trollop, ‘who’, she had said, being quite confident of her own charms, ‘probably looks like a Scarecrow anyway. I swear I will not wait for any man, and shall put to the greatest advantage your very convenient absence. I shall enjoy myself vastly and be seen everywhere about the Town, so that the gossips will say that Harriet is not the one to sit at home and twiddle her fingers while Bully Foulkes goes a-dallying elsewhere. Indeed, sir, you may depend upon it that the whole Town shall know that I have given you your congé.’ Which in truth dated from that very moment, for with a strength that surprised him she smacked his face and flounced out of the room, so that he had gone home in high dudgeon, promising himself at least the satisfaction of having his revenge on her by calling out any gentleman she might happen to favour. Not that his heart was affected in any way, for he prided himself on the fact that there were many other beautiful women who would be delighted to be seen in the company so splendid a fellow as Bully Foulkes. Yet these two rebuffs, vexing though they might be, were entirely swept aside by a curious feeling which the Captain had never experienced before. Certain words of the parson’s kept ringing in his ears. What was it the miserable fellow had said? ‘All the King’s horses and all the King’s men had never succeeded in catching him yet. Although he may permit you to reach the Marshes safely, it is very doubtful whether he will see fit to let you to return to London alive.’ These words in themselves would never have worried a man of the Captain’s stamp in the ordinary way, but upon reflection, he had to admit to himself that there was something about the way in which the parson had said them, and a curious sense of foreboding gave him an uncomfortable feeling in the pit of his stomach as he pondered that he might not return to London alive; and having permitted himself the luxury of an extravagant wager, he had, as yet, not the slightest idea of how he was going to carry it through. And so, cursing himself for not only jeopardising his reputation but also his life, and cursing his servants for their incompetent behaviours that morning, it was indeed the last straw when an unfortunate lackey was unable to secure a cabriolet to carry him to the coaching yard, which entailed making a spectacle of himself by running the length of St. James’s, and along Pall Mall to Charing Cross, sword flapping and wig awry, a breathless servant at his heels hampered by the weight of the valise, and derisive cries of errand boys ringing in his ears. In this unenviable state of mind and body, Captain Foulkes only just succeeded in reaching the ‘Golden Keys’ in time. The final indignity was being bundled in headlong by the infuriated guard, and the coach was moving off up the Strand.

* * * * *

Doctor Syn spent a very comfortable night at Haxell’s, in the Strand. It was a quiet and comfortable house, with good plain cooking and an excellent cellar, if you were popular with the landlord. Doctor Syn was popular with the landlord, who respected a country parson who seemed to be quite a connoisseur in French wines. Consequently Doctor Syn was ever a welcome guest at this family tavern, which was famed as a respectable country home in the hub of London life. Yes – the very place for a learned scholar who preferred the noise of the capital to be outside the windows, with quiet, well-mannered guests within. Haxell’s was also very handy to travellers who wished to catch the Kent-bound coach from Charing Cross, for you had only to inform the Coaching Counting House situated at the ‘Golden Keys’, which faced Duncannon Street, and the guard would reserve your seats and pick you up at Haxell’s on the way to London Bridge. Having on this occasion taken the precaution, Doctor Syn was under no anxiety about missing the mail, which pulled out at ten o’clock for the coast. He was called at half past seven with a dish of tea into which he poured a strong measure of brandy. Having ordered his breakfast for fifteen minutes past eight, and being dressed before it was ready, he strolled as far as St. Martin’s Church to encourage his appetite. The storm of the night before had cleared the skies, and he was welcomed by a pleasant sun, and cold, crisp air. His steps took him past the church and into Hedge Lane, famed for its book market. Many a poor scholar he found there before him, reading greedily from old volumes piled on stalls before the shops. To some of these Doctor Syn addressed a cheery good morning as he passed – with some of them he discussed the merits of a volume which the reader seemed tempted to purchase. Indeed, for one poor man he bought a book outright when he ascertained that the old fellow had not the money to indulge his taste, but called each morning just for the pleasure of holding it in his hand. Imagine the student’s gratitude for this generosity. It was indeed a gift from the gods, and had Syn been Jupiter himself he could not have received more adoration. Passers-by noted the elegant parson with the charming smile and stopped in pretence of viewing the bookstalls in order to watch him the more closely. Certainly he seemed to have done a great favour to the old student who, clutching his prized volume to his heart, kept bowing low before his benefactor while tears of gratitude ran shamelessly down his cheeks. Indeed it seemed that the parson was becoming embarrassed with such loud laudations, such hymns of praise, for he was overheard to say, ‘My dear sir, there is nothing more to be said. If that book is to be somebody’s property, that somebody must be you, since nobody could have shown me better than you what love a man may bestow upon a work of art. Besides, your taste is good. In all this great jangle street of literature you have found a gem. You appreciate its worth, and the regard you give to it but adds to its value. And pray do not thank me. It is for me to thank you for permitting me to spend a few coins in order that a great work shall be truly cared for. If that will not bring me a blessing – then blessedness is dead in our age. No more, dear sir, no more.’ Doctor Syn seemed to be attempting to pass on, but the grateful receiver of the book begged to know his name in order that he might remember it in his prayers. ‘You carry a pencil-case, sir, no doubt? Will you not writer your name for me in the fly-leaf of the book?’ With a smile Doctor Syn took a silver pencil-case from his pocket and wrote his name and address, which the old man, blinking through his spectacles, repeated aloud. The name brought the shopkeeper out on to the pavement, where, catching sight of Doctor Syn, he greeted him profusely. ‘So it was you, Doctor, who has proved to be this ardent bookworm’s benefactor. ’Tis like you, sir. And now I trust you will find that your goodness to a stranger brings you a reward. In short, I have a book for you within the shop. An agent from Paris left it for you. A French translation of the Æniad – a fine first edition, too, which I know you have long sought for. If you step in, reverend sir, I shall be glad to give it to you.’

Taking leave of the happy old student, Doctor Syn entered the shop and in a few minutes was handling tenderly the fine copy of Virgil referred to.

‘As I received it, I deliver it,’ explained the bookseller, ‘though I should like to remove these untidy slips of paper which some reader has cluttered it up with. Book-marks, no doubt. But they spoil the appearance of such a beautiful piece of printing. The fellow has undoubtedly torn up an old letter for the purpose. I cannot read the French myself. Used to regret it, having so many fine volumes in my shop that I could not understand. But since they started losing their manners as well as their heads, I have no mind to lose any sleep studying the language of such barbarians.’

Doctor Syn had already examined one of the slips in question, and with a twinkle of satisfaction in his eyes he answered: ‘This reader was at least not barbaric enough to mark the book with his own notes. Do not trouble to remove the markers. I will take them with the book. ’Twill be interesting to see if he has penned any erudite ideas.’

A quarter of an hour later the volume lay on the table beside Doctor Syn as he breakfasted in Haxell’s Coffee Room whose windows looked out upon the busy Strand. His walk had put him in good appetite and he thoroughly enjoyed a generous helping of grilled ham and eggs. But while waiting for the second cover, he picked up the book, and a close observer might well have been surprised to see him paying far more attention to what was written on the book-markers than upon the exquisite volume itself. He would have been more surprised still had he known what was written on those same book-markers. But why should anyone pay the slightest attention to such a normal sight as a scholarly cleric engrossed upon the French translation of a classic while enjoying a typical English breakfast?

And so, at five minutes past ten the warning notes of a coach-horn cleared the traffic in front of Haxell’s, as with a flourish and jingling of harness the Dover coach pulled up, and Doctor Syn stepped inside.

* * * * *

Yet another traveller had been awakened that morning in time to make preparation for the same journey. In the large bedroom of the best suite that the ‘Golden Keys’ could offer, propped up by pillows in a gigantic four-poster, sat a little old lady. From beneath the frills of a modish night-cap twinkled a pair of intelligent bird-like eyes, while over the rim of a tankard of small ale her aristocratic nose made her look like the proverbial early bird in search of the worm.

The small, shapely hands holding the tankard seemed to be weighed down by the vast collection of rings that she wore on almost every finger, while at her wrists innumerable bracelets jingled and flashed, as she gave orders to a French lady’s-maid. Beside the bed was perched an enormous white wig in the style that had been favoured by the ladies of the French Court, and which at the moment the maid was dressing. Upon the bed, curled up on the old lady’s feet, brushed and beribboned, looking like another wig, lay a white poodle, sleepily regarding his mistress out of one eye and paying not the slightest attention to the open jewel-case under his nose, for indeed he knew he was wearing his own jewellery – golden bracelets hung with little bells that tinkled merrily when he moved his two front paws.

Finishing her small ale with a gusto slightly incongruous for so frail a lady she put down the tankard and gave the tapestry bell-pull a vigorous jerk, which brought scurrying feet along the corridor, and an answering tap upon the door. The old lady raised herself and prodded the white dog with a playful bejewelled finger. ‘Come now, Mister Pitt. ’Tis time for your morning perambulation.’ Then, speaking to the maid: ‘Lisette, open the door for Mister Pitt, and tell the chambermaid to take him downstairs and see that he amuses himself in the yard. And see that he really amuses himself, for the poor gentleman will be cooped up in a stuffy old coach all day, and you know what happened on the journey to Aberdeen on my best tartan travelling-rug.’

With a disapproving sniff, Lisette swept the dog from the bed and handed him over to the chambermaid, returning to her work at the wig-stand and punctuating the rolling of each curl with a fresh sniff.

‘Whatever is the matter, woman?’ snapped the old lady. ‘Have you caught a cold? Can you not use your pocket handkerchief?’

To which Lisette – a solid, angular woman with the nimblest fingers and the slowest brain – replied with spirit: ‘Oh, madame, ’tis this ’orrid journey. Already we travel the week and no sooner do we arrive in a nice city like London than we must on again to this terrible place called Marsh. I talk ’ere with a serving-wench who say she will not visit Marsh for all the tea in China. Do you know, madame, that there they ’as terrible ’appenings. There are apparitions on horse-backs and they do say the sea is higher than the land, and I cannot see how that can be. Oh, madame, we shall drown!’

‘Fiddlesticks, woman!’ cried the old lady. ‘Serve you right if you did drown for listening to postboys’ tales. There’s a perfectly good sea wall that will keep you from paddling. Get on with my packing and give me my hand-mirror and the patch-box.’

Lisette did as she was told but continued protesting. ‘Madame is not of the nervous disposition, but after these tales I have the horrible nightmares. I do not want to go to this Marsh where the peoples are made crazy by living Scarecrows.’

‘Stuff and nonsense!’ retorted the old lady, snapping the lid of the patch-box, and sticking the latest fashion in patches on her powdered cheek, which, curiously enough, happened to be a tiny figure of a Scarecrow. ‘You know as well as I do that Romney Marsh is ruled by my own niece’s husband, Sir Antony Cobtree, whose house is within sight of your French coast. So if you don’t like the Marsh, you can paddle to Calais, where I warrant you’d have worse nightmares, if they were good enough to leave you a head to dream with.’ So saying, the old lady got out of bed, her frills and flounces quivering angrily as, no higher than the mattress she had just slid from, she announced, ‘For my part, I should rather like to meet this Scarecrow. I’d scare him.’

Which remark appeared to scare Lisette, who began to think that the horrors of her native France might be worse than the outlandish place she was about to visit. So she stopped grumbling, and knowing the old lady was ready for her breakfast did her best to hasten her mistress’s toilet, which was successfully accomplished by the time Mister Pitt returned from his amusement.

For so small a lady she partook of the largest breakfast served in the coffee room, criticising the abominable method of cooking porridge south of the Border, and praising the quality of the grilled steak, and the excellence of the cold game pie.

Allowing herself a glass of Madeira, she was, therefore, in the best of humours when the proprietor, anxious to please so distinguished a guest, personally escorted her to the coach. So despite her seventy-odd years, which she defied in a gay velvet travelling-dress, her face more bird-like than ever beneath the enormous white wig, and resembling from behind a miniature snowman wrapped in a white ermine cloak, Miss Agatha Gordon, of Beldorney and Kildrummy, stepped into the Dover coach, followed by Lisette and the barking Mister Pitt.

She settled herself in a comfortable corner facing the horses, and was tucked up snug in her tartan travelling-rug, Mister Pitt on the seat beside her. his two front paws on her lap, Lisette, still looking somewhat resentful at being swept up from the gay city so soon, took her place opposite, and the coach was about to start when there was a deal of noise and shouting above the sound of the horn, as the door opened and a gentleman was precipitated into the moving vehicle. He landed head first, almost in Miss Gordon’s lap, causing a shriek from Lisette, who dropped the jewel-case and surprising Mister Pitt so much that he continued to bark and bob about excitedly, while the gentleman, who seemed to be in the worst of humour, made curt apologies and tried to straighten himself out. Indeed this hullabaloo had only just died when the coach stopped again outside Haxell’s in the Strand. The door was opened and in stopped a clerical gentleman for whom it appeared the other corner seat facing the horses had been reserved.

And so, ten minutes later, with passengers and mails complete, yet several hours behind Gentleman James and Lord Cullingford, the Dover coach rumbled its way across London Bridge.

Chapter 3

The Little Affair of the Dover Coach

A mile or so beyond Canterbury at the beginning of the long stretch of Roman road, known as Stone Street, Gentleman James reined up, and allowed his tired horse to nibble the fresh grass that fringed the footpath. He turned in his saddle and listened. All the morning he had been aware of a horseman not far behind him, having heard at every turnpike the sound of hooves thundering in his wake. Thinking it might be a Bow Street Runner, he had spurred his own horse on and kept well ahead, but now deep in his own territory and knowing that but a few miles farther on he had a safe ‘hide’ where he could be freshly mounted on his favourite horse, he thought it advisable to ascertain exactly who it was that rode so furiously. So he turned his horse off the road and took cover in a convenient coppice, where, unseen, he commanded a clear view of the straight road. Sitting comfortably in his saddle, he waited. It was noon and the promise of the early morning had been fulfilled. The racing clouds had been swept seawards, the sky was high and clear, and a generous sun warmed his back. An exhilarating morning, and Mr. Bone was extremely glad to be back at work again. As all master craftsmen, he was in love with his job, and this one promised to be both amusing and profitable. He had not long to wait, for in a few minutes the figure of a horseman topped the distant slope and was silhouetted against the white road. He could now see the rider distinctly. Here was no Bow Street Runner – Mr. Bone knew them all only too well. Nor was it a riding officer of the Revenue, for he knew them too. At a hundred yards distant Mr. Bone summed up the stranger in his mind, having decided already not to waste time upon small fry that morning, and this, though obviously a gentleman of fashion, was small fry. He rode well, and Mr. Bone admired a good rider, yet he must be in a devil of a hurry, for the fine animal beneath him, flecked white with foam, showed signs of hard going. ‘The manner of his riding and his extreme youth,’ thought Mr. Bone, ‘suggest one of two thing. He rides either to visit a pair of sparkling eyes and get them before a rival, or on some business which may fill his purse with guineas. In which latter case,’ chuckled Mr. Bone, always an opportunist, ‘the luck of the road may deliver him into my hands on his return journey.’ With this cheering thought in mind, Mr. Bone graciously allowed the traveller to go unmolested, and Lord Cullingford, unaware of the danger to the last few guineas in his pocket, spurred the tired mare on towards the coast.

At a leisurely trot Mr. Bone, now satisfied that at least there was no immediate concern that the Revenue were on his tail, proceeded along Stone Street, turning off down a narrow lane to the right and making his way to a farm-house that lay in a hollow unseen from the road.

Here he was greeted by his old friend who gloried in the nickname of Slippery Sam – a name well earned by his ingenious method of escaping the long arm of the Law, for on the occasion of his being surprised one night by a party of King’s men, who were about to batter down his bedroom door, he smeared his naked body with oil, flung open the door and challenging his pursuers to get a grip on him, thus slipped through their fingers. A tall middle-aged man with a bald head and a squint, he had a great liking for the carefree highwayman. In fact, he and Missus Slippery treated him as the son they never had. So Jimmie Bone was given great welcome; his horse was led to be rubbed down and fed, the saddle removed and put on his own favourite black horse. The three of them then repaired to the farm kitchen where Missus Slippery fussed and mothered him, the while he received news from Sam of the latest activities of the Scarecrow’s men, in exchange for Mr. Bone’s information concerning the London Receivers.

Knowing that he had an hour or so to his credit, Mr. Bone allowed himself the luxury of complete relaxation. With the wing of a chicken in one hand and a foaming tankard in the other he exchanged confidences and he felt, as indeed he was, prince of the road.

It was while Mr. Bone was in this enviable position that the coach came down Strood Hill and then with horn blowing gaily, rattled across Rochester Bridge. The four occupants by this time had become more or less acquainted through such close proximity, though for some time after leaving London the Captain had appeared aloof and ill-mannered. It had by no means improved his temper that he had to sit with his back to the horses, and, having been so rudely bundled into the coach, it was annoying enough when the coach stopped again so soon after Haxell’s to pick up, as he thought, such an insignificant passenger, who had bespoken the only other comfortable seat. A parson was the last person he had wished to travel with, for his mind still rankled when he thought of his encounter with one at Crockford’s.

Imagine then his rage upon closer examination when the coach had left the City and the daylight streamed through the windows to discover that here he was cooped up with none other than that confounded cleric who had so quietly scored off him the night before. Coupled with the warning he had received, the uncomfortable feeling he had hoped to forget was increased a thousandfold by the presence in the coach of its instigator. So he had turned up his collar and glared in sulky silence out of the window, purposely ignoring the fact that they had met before, at the same time somewhat mystified that the parson did not seem to recognise him. To feign sleep was out of the question owing to the continual barking of that confounded dog and the perpetual chatter of the little old lady who, damme, appeared to have another poodle on her had. And so he continued to sulk and stare.

Miss Gordon, on the other hand, had found a fellow traveller to her liking, for Mister Pitt, contrary to his habit of being thoroughly rude to strangers, had swept aside all social barriers, and with much jingling of bracelets, he had attempted to lick the parson’s nose. Miss Gordon, though secretly delighted, had pretended to be horrified, as she exclaimed, ‘Fie, Mister Pitt, manners, please. What a rude gentleman we are. Lisette, lift the Minster of War off the minister’s lap.’ Whereupon Mister Pitt showed his warlike tendencies by worrying with obvious enjoyment one of the Captain’s silver coat-buttons. The old lady had then produced a miniature handkerchief edged with the finest lace and handing it to the parson requested him to use it.

Doctor Syn, declining, was amused and charmed and settled down to enjoy her lively wit, while Miss Gordon, making a mental note that she must remember to reward Mister Pitt for introducing to her such a delightful travelling companion, prattled gaily.

‘I am indeed felicitated that we are bound for the same part of the coast and quite overwhelmed that I should be talking to the famous Doctor Syn whose ecclesiastical books are widely read by our ministers in Scotland. So you see, Mister Pitt, what a clever dog you are to have recognised such a well-known figure. Is he not like his namesake, sir,’ she said, ‘in bestowing honours where honours are most due’ – and she laughed so infectiously that Doctor Syn quite looked forward to the remainder of the journey, and was delighted to discover that she was a relation of his old friend, Sir Antony Cobtree, to whom she was paying a visit.

‘Then I vow, madame, you are no stranger to me, for I knew your niece, Lady Cobtree, before she married Tony, and your name has ever been a household word in the family. Indeed, on more occasions than I can remember I have heard Tony refer to “me wife’s Aunt Agatha”.’ Here Doctor Syn gave such a graphic imitation of the Squire of Dymchurch that Miss Gordon was quite paralyzed with giggles. ‘’Tis Tony to the life. You have caught his excellent pomposity. But he’s a good boy. I have ever been fond of him, though I think he regards “me wife’s Aunt Agatha” as a most eccentric old body, and what he will think of me now I hardly dare think, since it is many a year since I have visited them. Indeed, sir, the last time I was in Dymchurch was when you must have been away in the Americas. They often spoke of you. I was deeply distressed to learn of my favourite niece’s death. Poor Charlotte. She was so young.’ Engrossed in her family reminiscences, she failed to note the look of pain that for a moment clouded the Doctor’s face on her mentioning the name of Charlotte. ‘But tell me,’ she went on, ‘what of Cicely? I hear she is a fine girl. Good rider too. That’s to my liking. Indeed, she is my god-child. And thank heaven for that, since I never could abide her elder sister Maria. ’Twas a great blow to Caroline and Tony, as you must well know, when Maria went off and married that French nincompoop, though naturally now they are in a great state about her, and no wonder. To have a daughter of Maria’s disposition in the midst of these Paris horrors must be more than worrying. Indeed, I had a long letter from Cicely upon that subject before I left Kildrummy. It seems that the poor girl is worrying herself to a fiddle-string about her sister, though goodness knows Maria never cared a fig for anyone except herself. But tell me, Doctor Syn,’ she continued, ‘is not the position serious? – especially as we are now at war with France. Tony, with his English insularity, is often apt to deceive himself. I can almost hear him saying, “Damme, they’d never dare to touch a Cobtree. She may have married a Frenchman, but she’s still my daughter, sir.”’ Which rendering was as perfect an imitation of the Squire as Doctor Syn’s had been, which amused them both considerably, but returning almost at once to the seriousness of the situation, she added: ‘But I have a notion that that French husband of hers is not worth his salt and would be far too concerned for his own safety than to worry over Maria’s. For I am not sharing Tony’s convictions, and am quite certain after what they have done to their own Royal Family, one Cobtree more or less wouldn’t worry ’em.’