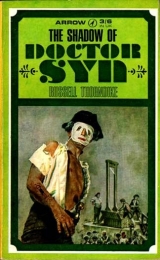

Текст книги "The Shadow of Dr Syn"

Автор книги: Russell Thorndike

Жанр:

Исторические приключения

сообщить о нарушении

Текущая страница: 1 (всего у книги 16 страниц)

The Shadow of Doctor Syn

by

Russell Thorndike

1944

‘Serve God; honour the King; but, first maintain the Wall.’ Slogan of ROMNEY MARSH

To

Emma Treckman

with grateful thanks for

her collaboration

Chapter 1

Two Topics of the Town

In the year 1793, not only in the isolated taverns of the remote district of Romney Marsh, but in the fashionable clubs of London, two subjects of news were passed from mouth to mouth, and were discussed in leading columns of the papers. The first of these was the Reign of Terror, raging across the Channel – terrible and bloody. The second, and perhaps more popular, because of its humour, the latest exploits of the mysterious Scarecrow, who, in spite of the danger in France and the unpopularity of the British with the French, managed to keep successful his mighty organisation of contraband running, backwards and forwards across the Channel.

Even the most literary of the political periodicals found space enough to exploit the adventures of the Romney Marsh smugglers, in the same editions that screamed out execrations against the murderous Paris mob. Indeed they used the Scarecrow and his men as an excuse to howl against the Government, which seemed quite powerless to put the audacious scandal down. True, they had offered a thousand-guinea reward to any person who should hand over, or cause to be handed over, this notorious malefactor, alive or dead, but although this sounded a large sum in proclamation, it was nothing when compared to the many thousands which were slipping through the fingers of the Revenue.

‘In the devil’s name, who is this Scarecrow?’ was the question on everybody’s lips. The general opinion was that he must be a man of education, since it was known that he spoke French fluently and was as powerful in the coastal districts of France as he was in his own territory of the Marsh. But on both sides of the Channel his real identity was unknown. He was the Scarecrow – L’Épouvantail. Well, whoever he was, he was certainly a public benefactor. To the vast majority his adventures were a joy. His audacity made the world chuckle, while locally he was keeping his followers’ necks out of the Government’s noose, and by risking his own he made the poor rich, so long as they obeyed his orders, and played the dangerous game against the Revenue men, according to his rules.

There were other adventurers who played a dangerous game without adhering to any code of fairness, and one of these was Captain Foulkes, a successful gambler and soldier of Fortune. Oh yes, ‘Bully’ Foulkes, not without reason given this nickname, played for the highest stakes in the most exclusive London clubs. He cheated so cleverly that his fashionable victims innocently paid their losses and called them debts of honour when trying to balance their accounts. Whenever Bully Foulkes was accused of not playing fair, by gentlemen who were not quite so innocent in the ways of roguery, the noble Captain was so insulted that he sent his second immediately to arrange a meeting. This was not a very risky thing for the Captain to do since he happened to be brilliant with sword or pistol. He had to his record twelve gentlemen whom he had spitted in St. Martin’s Fields, and seven he had shot dead at Chalk Farm Tavern, where such matters were dealt with conveniently to all parties. Yes – a brave man might well think twice before meeting Captain Foulkes in an affair of so-called ‘honour’.

Yet he was not without disciples – young men of rank and fashion who admired his dash and tried to emulate his success. Such a youngster was Lord Cullingford, who, having recently come into his family title, found that he had mortgaged the next three years of his income.

He had raised the money from the City Jews in order to satisfy his creditors. But since it was utterly impossible for a young lord of the realm to live in the lap of luxury without a penny piece for three years, these same kind financiers advanced him a further sum, which, banked, would bring him in sufficient for his needs. Unfortunately the noble lord did not bank the money. Instead he cut a great dash with it, and for a few glorious and hilarious weeks managed to make himself the envy of his rivals, the other young dandies who roistered in the company of Captain Foulkes. Indeed, while the money circulated, he was raised to the rank of the Captain’s boon companion, and was privileged to swagger arm-in-arm with him when taken the air in St. James’s. The Captain permitted young Cullingford to imitate him, knowing that this was a form of flattery, and being well aware that, while the money lasted, the vain and stupid fop could never eclipse him when they were seen together.

Captain Foulkes cut a fine figure, tall, broad shouldered, athletic. Cullingford was not so tall, thin shouldered and effeminate. But the tailors managed to pad out his shoulders, and the bootmakers elevated his feet, while the Captain’s personal barber attended on him. In fact, the general opinion was that Cullingford’s friendship with Captain Foulkes had improved his looks and bearing considerably.

One miserable night in late autumn Lord Cullingford left the gaming-table at Crockford’s and strolled over to the fire. All day he had played cautiously, which is often an ill thing for a gambler to do. On this occasion it was certainly an ill thing for his young lordship. As he gazed into the flames, his mental arithmetic told him he was down to his last three hundred pounds, and was owing to various tradesmen. His credit was good enough, since none of the tradesmen in question were aware of the precarious state of his purse, but having tasted the dubious honour of being the chosen companion of so envied a man as Bully Foulkes, he had no desire to be given his congé. Foulkes had no use for anyone who could not stay the course. An ignominious position to be in, and one thing was certain to his lordship – he must play no more tonight. In fact, Lord Cullingford was very sorry for himself. His nerves, none too good, from a succession of routs and late parties, were strained to the highest tension, when a burst of noisy laughter from the table behind him aggravated them beyond bearing, which decided his lordship to go home to bed, thinking that a stroll up St. James’s in the fresh air would dispel the fumes of wine from his head and his financial worries with them.

As he turned to put his resolution into practice, Bully Foulkes pushed back his chair, swept a pile of guineas from his place at the table, and swaggered over to him.

‘Come on, Cullingford,’ he said; ‘my luck is in, but I’m quitting for an hour as I have an appointment at Bucks. Take my place.’

‘Oh, the devil damn the rascal that first thought of cards and dice!’ snapped his lordship. ‘I’ve lost all day and will play no more.’

‘Then take my place and perhaps your luck will change all night,’ replied Foulkes. ‘And damme, I hope it may. You’ve been an ill enough companion for the past week, and if there is one thing I can’t abide ’tis a poor loser.’

‘I tell you, man, I have no wish to play and am going home.’

‘I vow you’re as sulky as the bear in Southwark pit,’ laughed the Captain, taking his arm. ‘Come, a glass of brandy will cure your spleen and a rattle of dice will take that sour expression from your face. My place is reserved for you. I beg you to take it and try one throw. A hundred guineas round the table and the highest takes the lot. ’Tis a quick way to earn a thousand, and I warrant a thousand guineas will soon cure you of the sulks.’

‘I’m bored and tired – not sulky,’ replied his lordship, trying to free himself from the persuasive arm that was leading him towards the empty chair.

‘Take the throw yourself as your luck’s so good.’

The grip on his arm tightened as the Captain’s voice took on a bantering tone. ‘Never change my mind. ’Tis a good rule which helps a man never to break his word. Don’t be a fool, Cullingford. Play.’ There was something dominating about Foulkes which Cullingford, to his cost, had always found difficult to resist.

‘All right. One throw – and damn you, Foulkes, if I lose.’

He went to the table. He threw. So did nine other gentlemen. Foulkes’s place had served him well that evening, but it did no miracle for Cullingford. He lost.

‘Try again,’ cried Foulkes, who now seemed in no hurry to leave. His unfortunate victim, already flushed with excitement and subject to the gambler’s delusion that this one throw will bring a run of luck and retrieve all, called his opponents to cast again.

Again he lost, but stung by what Foulkes had said he challenged the gentlemen to double the stakes.

The loud rattling of the dice-boxes answered his lordship’s wager, and the enthusiastic cries of acceptance to a sporting bet in no way disturbed the flow of polished conversation being carried on by three gentlemen in a remote corner of the room. Seated at their ease, near a glowing log fire, they smoked, sipped a fine old brandy, talked and listened, as cultured men are wont to do who admire and respect each other, knowing that each, in his own way, is master of his calling.

Indeed, it was a remarkable trio, and had the interest not been so high at the gaming-table, the more curious might have wondered why a dignitary of the Church should be in the company of two notables of the Theatre, but he was listening with the greatest attention and obvious enjoyment. Here was no ordinary parson. Although dressed in the sombre black of his calling, the cut of his clothes and the way he wore them might have put to shame any of the well-known dandies present. Relieving the severity of the clerical garb was the exquisite white linen at neck and wrists, and the slim hand holding the brandy glass denoted a man of taste and refinement. The fire-light played on the silver buckles of his elegant shoes as, legs crossed, one elegant foot slowly swung to and fro. His free hand swept back a stray lock of hair which he wore long and loose to his shoulders and unhampered by the ribbon of the day. Indeed he was setting a new fashion for the clergy, who still wore the formal white wigs. But for his glasses and the slight scholarly stoop of his shoulders the casual onlooker might have taken him for a younger man, since his hair was still raven black, making an unusual contrast as it framed a face pale and classical. In repose it might be the face of a man who had lived and experienced much, but at the moment his features were full of charm as he expressed contentment with the luxurious surroundings and gay companions. In fact – Doctor Syn, D.D., Vicar of Dymchurch-under-the-Wall and Dean of the Peculiars of Romney Marsh, was enjoying himself. Proffering a snuffbox to his companions, he remarked: ‘Yes, indeed, Mr. Sheridan, the loss of Garrick dealt a sorry blow to the Theatre, but it has ever been a puzzle to me why you of all people should have forsaken Old Drury for Westminster.’

‘Pray, Doctor Syn, do not encourage Richard on that subject,’ laughed the youngest of the party, ‘or we shall have an eloquent lecture lasting all night.’

‘Indeed, Mr. Kemble – and begging your pardon, sir, you being manager of Drury Lane,’ replied the parson, ‘but I vow I have not seen a play to my liking since Mr. Sheridan’s School for Scandal. So I trust you will prevent the Theatre from going to the devil, for that indeed would be a further bar to the fulfillment of my ambition.’

‘Yes, you would have made a good Hamlet, Doctor Syn,’ said Mr. Sheridan, ‘for apart from your natural qualifications, they say that the Church is closely akin to the Theatre, and were I still manager of the Lane, I’d engage you here and now, but I vow no one will get a chance with Shakespeare now the Kembles are come to Town. Your brother’s first appearance has been a great success, I’m told.’

Philip Kemble smiled his acknowledgment to Mr. Sheridan’s tribute and, turning to Doctor Syn, said laughingly: ‘My brother Charles promises to make a fine comedian, sir, so that you and I, of sterner stuff, need have no fear of a rival there. But plague take it, Sheridan is almost right about the state of the Theatre, since the one topic the public wish to hear about is the latest playacting of this confounded Scarecrow. Now there’s a great actor and a comedian too, eh, Sheridan? And he is one of your parishioners, Doctor Syn, is he not?’

‘Come, Kemble,’ cried Mr. Sheridan. ‘I may now turn the tables on you; for should you encourage Doctor Syn to pursue that subject we shall have an eloquent sermon lasting all night. Do you not know that his orations against this rogue are highly thought of in all circles?’

Doctor Syn laughed, and addressed the young manager of Drury Lane. ‘I had a mind to rehearse my next Sunday’s sermon to you and Mr. Sheridan, so that you might gauge the quality of my acting, but after such a neat example of table-turning, I will refrain; and indeed, he is right; it would take all night, for I have planned a most vehement one, and ’tis time a poor old parson in his dotage were a-bed.’ So saying he rose from his chair and stood awhile by the fire.

Mr. Sheridan watched him, noting the easy grace and dignity of his bearing. Then smiled and said: ‘Your claim to senility is ill-founded, sir, and carries no conviction. Indeed, I fail to see why you should wish to add to your years. For my part, I’ll warrant, you are as youthful and virile as any of those foppish fire-eaters yonder’ – indicating with his brandy-glass the crowd round the gaming-table.

‘I thank you for the compliment, my dear Sheridan,’ said Doctor Syn. ‘But pray, in truth now, would you not prefer a comfortable dotage to that strident-voiced braggart yonder?’

‘Egad, you’re right, ’tis Bully Foulkes. The most insolent and tiresome dog in Town, though ’tis not the policy to say so to his face. I have no wish to be called out. St. Martin’s Fields are too damned chilly in the early hours of the morning. So have a care, Doctor Syn, when you refer to the stridency of his voice, though of course your calling protects you from the rogue.’

As they were talking the noise round the table grew louder and a heated argument took place, in which this said gentleman seemed to be the central figure. Loud oaths and proffered bets reached the far corner of the room, and the Captain’s voice took on a bantering tone. ‘The Scarecrow. I am heartily sick at the very sound of his name.’

‘Because his adventures are fast eclipsing your own, eh, Foulkes?’ cried a voice from the far end of the table.

‘Have a care, Sir Harry,’ warned Foulkes, with an unpleasant edge on his voice, ‘when coupling my name with that of an ill-bred smuggler from some outlandish place in Kent. Confound it, why can’t the Government rid us of this rogue? Easiest thing in the world if you’ve the brains and ingenuity, and for two pins I’ll do it myself.’

‘The Government will give you more than two pins should you succeed,’ replied Harry Lambton. ‘A thousand guineas is their latest offer, and I vow I am as bored as you are with the subject. ’Twould be a relief to get back to normal and lay our wagers on the colours of Mrs. Fitzherbert’s latest gown. I’ll gladly add another thousand to the Government’s, should you succeed in ridding the Marshes of the Scourge and the Town of this plaguey topic.’

The offer was greeted with loud applause, and in the excitement and speculation that followed no one noticed the dejection of young Lord Cullingford and the look of blank despair on his face. He cursed himself for having listened to Foulkes, not daring to think how much the evening’s rash play had let him in for and knowing that his fair-weather friend took occasion to quarrel with anyone who kept him waiting for the payment of a debt. As in a dream he heard the voices round him. ‘The Government offer a thousand guineas and Harry Lambton doubles it.’ He was desperate and must clutch at any straw. In a flash he made up his mind. Whether Foulkes went or no, he determined to try himself. One thing was certain, he must get on his way before Foulkes. Thank heaven there was one remaining horse in his London stables and that a good one. He determined to start at daybreak, and with the possibility of earning so large a sum his courage returned and he made a rapid calculation of his night’s losses. If he should succeed he reckoned he should have funds enough to keep him till he was on his feet again, and so with glowing prospect in mind he was able to face the Captain with his usual gaiety.

‘Why, Foulkes,’ he cried, ‘’tis the first time I have known you to hang back on a bet. Or is it that you daren’t leave Town in case I cut you out with La Belle Harriet? Should it relieve your mind suppose we all promise not to call upon her till you return victorious?’

Stung by the youngster’s banter into a quick decision, Foulkes replied hotly: ‘I have yet to meet the rival that I fear will oust me in the affections of any woman, just as I have yet to meet the man whose bet I will not take. I accept your wager, Sir Harry, and if I fail I’ll double the stakes.’ An even louder cheer greeted the acceptance.

Then Sir Harry spoke. ‘You’re a brave man, Foulkes, and ’tis a sporting thing to do, but have a care. You may not get as far as Charing Cross. Then poor Harriet will have a long wait, since we all pledge we will not visit her till your return. I take it there should be some sort of time-limit?’

‘Ten days should be all I need,’ replied the Captain. ‘And I’ll set off tomorrow on the morning Mail, so you meet me here today fortnight to settle accounts. I’ll now go and convey to Harriet the reason why her salon will be deserted, though I warrant she will not mind waiting for me. Come, drinks all round, and I’ll give you a toast.’

Glasses were filled and Captain Foulkes being once more the centre of interest became his ostentatious self. He strolled over to Cullingford and put a patronising hand on his shoulder. ‘Poor Cully,’ he said. ‘You’ve had damnable luck tonight, but I’ll take your I O U and will not call upon you till tomorrow week.’

It was while the glasses were being charged that Doctor Syn took his leave of Sheridan and Kemble and was strolling past the gaming-table on his way to the door. For the first time the Captain became aware of the parson’s presence and in his growing mood of arrogance put himself in the way. ‘Zounds,’ he cried, looking Doctor Syn up and down in an insolent fashion. ‘A parson – in Crockford’s? Are you seeking the devil in cards and dice?’

‘No, sir, I have known both cards and dice all my life and I have learned that they are innocent enough. Unfortunately the devil is sometimes in those who handle them. Your pardon, sir,’ and Doctor Syn would have passed on but the Bully did not intend to lose this chance of amusement.

‘A neatly turned phrase, sir,’ he said. ‘Come, give the parson a glass and he shall drink my toast. Are you ready, gentlemen?’ Glasses were raised in assent and the Captain proposed: ‘Damnation to the Scarecrow, and may he not escape Bully Foulkes.’

The gentlemen drank, but when Foulkes lowered his glass he perceived that that parson’s wine was still untouched. ‘You did not drink, Parson. Did you not understand the toast? Being at Crockford’s I thought you had a London living. But perhaps your parish is so remote that you have never heard of the Scarecrow.’

‘I did not drink, sir,’ replied Doctor Syn, ‘because I thought it unseemly to drink damnation to one of my own parishioners.’

The atmosphere was tense and the gentlemen present listened in delighted silence. A parson was getting the better of Bully Foulkes, who at the moment appeared to be at a loss for words. The next move came from Doctor Syn, who continued politely: ‘I could not fail to overhear your bet, sir. Drink damnation to the rascal by all means and you will be in good company, for he has been damned by Army, Navy and Revenue alike. But all the King’s horses and all the King’s men have never succeeded in catching him. A thousand guineas. Oh, I beg your pardon. Two thousand guineas, for you doubled the stakes, is a lot of money to lose, though nothing to losing one’s life. I feel ’tis my duty to warn you – knowing something of this rascal’s methods, indeed, having been one of his victims – that although he may permit you to reach the Marshes safely, it is very doubtful whether he will see fit to let your return to London alive.’ Doctor Syn glanced round with an almost apologetic air, and then handing the glass still untasted to the Captain, he added regretfully: ‘I do hope I have not depressed you, sir. Good night – Good night,’ and before the astonished company had well recovered, the parson had left the room.

None of the gentlemen dared speak, fearing that the Bully thwarted might be in an evil mood. He broke the silence himself. ‘Who in the devil’s name was that? And what does he mean by claiming to be one of the Scarecrow’s victims?’

Sir Harry Lambton supplied the information. ‘Why, did you not know? I thought Doctor Syn was as famous as the Scarecrow. He is the Vicar of Dymchurch, and his courage in preaching against this rogue is highly spoke of. Threats do not stop him, though he has had many warnings, and on one occasion he was actually lashed to the gibbet post in company with a Bow Street Runner. A learned man – well travelled – indeed, no ordinary parson.’

‘And how have you managed to glean so much information about him?’ growled the Captain.

‘Oh, my informant is a great friend of his and one whose word you must believe in unless you are seeking lodging in the Town. ’Twas none other than the Prince of Wales himself.’

‘Yes, indeed,’ said another gentleman, emboldened by Sir Harry’s attitude and the mention of the Royal name. ‘’Tis all over the Town that the handsome snuff-box Doctor Syn carries was given him by the Prinny himself, who maintains that Syn is the only parson who can make him laugh.’

‘Devil take it,’ replied the disgruntled Captain. ‘I don’t know what he finds to laugh about, for I never saw a more sombre figure in my life.’

Standing at the Captain’s side, Lord Cullingford had missed nothing and he vowed that upon reaching Dymchurch he would present himself at the Vicarage and seek assistance from such a learned gentleman.

This same learned gentleman was at the moment seeking assistance elsewhere, for having made his way to the writing room he sat penning in fine scholarly handwriting a lengthy list of instructions. An enigmatical smile changed the gravity of his face to an expression of impish humour as he wrote the address and planned how it should be delivered to:

Mr. James Bone , at the Mitre Inn , Ely Place , Holborn .

Chapter 2

Two Beaux in Search of One Topic

Mr. James Bone was in an excellent humour, in spite of the fact that he had not been to bed all night. He was warm and comfortable: sprawled at his ease in a well-padded armchair, feet on the mantel, the logs still glowing in the fireplace of one of the many back parlours of the Mitre Inn. Beside him was a tankard of ale heavily laced with spirits. On the same table as the tankard a branched candle-stick gave sufficient light for him to read once more the letter which had put him in such a pleasant frame of mind. With a final chuckle he rose, took a long draught from the tankard, and with a yawn of satisfaction, raised a well-booted leg and kicked the logs into a blaze. He then dropped the letter into the heart of the flames and watched it burn. Gentleman James left no traces, and had memorised the instructions he had received, word for word. A glance at his handsome fob watch told him that he had plenty of time before starting to carry them out. Stooping his great frame to enable him to see into the mirror that hung over the fire, he straightened his cravat and retied his hair-ribbon. The picture that he saw did not displease him. A weather-beaten face, maybe, but attractive enough, especially when he allowed an engaging smile to wrinkle the corners of his eyes, blue and merry, as many a serving-wench knew to her cost; though ’twas not only these buxom lasses in the inns on the Dover Road who fell for his attractions; many a fine lady or London beauty going visiting by coach wished to see more of Gentleman James in spite of the fact that he may have taken their diamonds. A likeable fellow, who had learned early in his career that to have ladies on one’s side was half the battle. His easy grace and polished manners had earned him the name of ‘Gentleman James’. Indeed there was not a lady between London and the Kent coast who would give information to the Bow Street Runners against so charming a rogue. But politely relieving the fashionable travellers of their valuable gewgaws was not Mr. Bone’s only occupation. He it was who superintended the vast organisation required on the road for moving the Scarecrow’s contraband to its various destinations. There was not a ‘hide’ in cottage or castle in Kent with which he was not familiar. No wonder that the Bow Street Runners were hard put to lay him by the heels. At the moment, when we first meet him he was just emerging from an enforced vacation after a rather tricky affair on the Chatham and Maidstone Road.

Feeling in need of breakfast, he went to the door and called for the serving-girl. Her prompt appearance suggested that she also had been up all night, and her rosy face told him that she wished he had called for her earlier, through her speech belied this.

‘What a time to get a poor serving-wench out of her bed,’ she teased. ‘I vow I would not do the same for the Prince himself.’

‘Then I vow I would rather be Gentleman James than all the crowned heads in Europe,’ he said, giving her a resounding kiss. ‘You’re a good lass, Dolly, and prettier than many a fine lady I know. I only wish I could stay here longer, but in half an hour I take to the road to gain the top of Shooter’s Hill by dawn, so do you bring me some breakfast now, and make it a hearty one for the Bow Street Runners are apt to interfere with the regularity of my mealtimes.’

‘So long as it’s only the Bow Street Runners and not them Kentish Jezebels, then Dolly will do your bidding.’ She laughed and hurried off to the kitchen, adding: ‘’Tis all prepared. I have only to bring it in.’

Mr. Bone went to the further corner of the room, where carelessly flung over a chair was his great caped riding-coat, beneath which were his pistols in their holsters. These must be in perfect working order, and indeed were his pride and joy, having lifted them a few years earlier from a Colonel of Dragoons who had evidently known how to purchase fine weapons. Mr. Bone took them to the table, and, sitting down, cleaned, primed and polished. He was engaged upon this vital task and was nearly finished when Dolly came bustling back, tray piled high with pewter covers and a flagon of mulled ale.

Gentleman James set to, while Dolly hovered to anticipate his every want, for which she was rewarded with another kiss and a bracelet which Gentleman James had kept back from the receivers.

Ten minutes later Gentleman James was thundering across London Bridge and in less than an hour he saw the dawn breaking from the summit of Shooter’s Hill.

* * * * *

The weather had cleared. There was still a high wind blowing, but the direction of the blown clouds and the clarity of the morning star gave promise for a fine, crisp, autumn day. It was yet the small hours but my Lord Cullingford was already wide awake, having had a poor night, sleeping fitfully and haunted by dreams of the Scarecrow who, at Crockford’s, had seemed such an easy solution to his problems. Surrounded by laughing companions without a care in the world and exhilarated by good wine, the horror had seemed remote enough; but now alone, and in the coldly calculating hours of early morning, Lord Cullingford felt extremely frightened, rather small, and of no account. Alone in his great Town house, unable by his penury to retain his servants, he had conjured up terrifying visions of the creature he had sworn to himself to seek. In fact, to poor Lord Cullingford, the Scarecrow had assumed gigantic proportions; every shadow made him shudder and every night noise in that vast old house made him jump. In fact, Lord Cullingford, in Marsh language, had a bad attack of ‘the dawthers’.1 1 Trembles. Although he did not know it, he was not as cowardly as he thought, for many a braver man than he, trained to danger and employed by the Realm, had worse than ‘the dawthers’ when ordered to confront the Scarecrow or his gang. Cursing the fact that he had no servant to help him dress nor to bring him a cup of chocolate, at least, before setting out, he struggled by the flickering light of one solitary candle with breeches, hose and riding-boots. Another thought too was worrying him and an equally unpleasant one at that – the presence in the Captain’s pocket of his I O U for a thousand guineas. ‘The devil rot Bully Foulkes,’ he said aloud, and his voice went echoing to the lofty painted ceiling. ‘Bully Foulkes.’ ‘Had it not been for him,’ he thought, ‘I should not be in this confounded predicament. I vow, if I get out of this alive, I’ll see him in hell before I consort with him or his kind again.’

Feeling more the man as he got into his handsome riding-coat, he permitted himself one ray of hope in the dark uncertainty before him – the Vicar of Dymchurch. A kindly, learned man this Doctor Syn had seemed last night. Had Cullingford felt better he would have chuckled at the remembered scene, of the parson getting the better of the Bully. As he pondered on this, it struck him that from the moment Foulkes had been so truculent and ill-mannered towards the dignity of the Church, he had gone down in his estimation, and was no longer an idol in the eyes of his disciple. Cheered by the thought of visiting Doctor Syn, and the possibility of having his assistance, he made his way along the gallery and down the sweeping stairs.

Holding the candle before him, he was just able to see his way. Egad, the house looked miserable enough. Great dusty marks were on the wall where pictures of his ancestors should have hung, and dust-sheets covering such furniture as was left. ‘Property,’ he thought, ‘’tis but a millstone round a fellow’s neck.’ Then, filled with shame as the accusing spaces on the walls above him seemed to answer back, ‘Yes, but in our day this house was well run, well loved, and filled with beautiful people,’ he crossed the hall and went into the library.