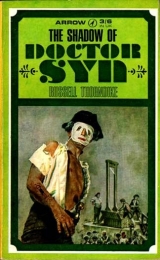

Текст книги "The Shadow of Dr Syn"

Автор книги: Russell Thorndike

Жанр:

Исторические приключения

сообщить о нарушении

Текущая страница: 8 (всего у книги 16 страниц)

Mr. Mipps was so busy with his lack of inches that he did not notice that the front door had opened quietly and around it peeped the face of Cicely.

The voice from behind the lectern continued: ‘You ability for acquiring knowledge of current affairs, Mr. Mipps, would make me respect you were you a giant.’ This was too much for Mr. Mipps and he retorted quickly:

‘And your ability for making yourself laugh may get us all in a trouble, and I weren’t at no key’ole when I ’eard that. Miss Cicely called her a goose, but I can think of a adjective; in front of them Dragoons too. Now look ’ere, Cap’n, if you persists in rollin’ up your sleeve, we’re sunk.’

It was then that Cicely decided to knock upon the door, causing Mr. Mipps to turn round as if he had been shot. Upon seeing her he relaxed, and when she beckoned to him he went quickly towards her.

‘Mr. Mipps,’ she whispered, ‘has Mr. Scarecrow gone?’ He was delighted to see her. He grinned. ‘Yes, miss,’ he nodded assuredly. But was this the right answer? He hadn’t looked behind the lectern. Was it Doctor Syn or the Scarecrow? He decided on a middle course. ‘I don’t know, miss.’ Oh, better be definite. ‘No, miss.’ Oh dear, he was still doubtful. ‘Yes, miss.’ Oh, better not to have heard at all. ‘What, miss? What did you say, miss?’

‘I said I’d lost my gloves, Mr. Mipps.’ What a relief, perhaps he hadn’t heard right after all. ‘Oh, your gloves, miss,’ he said with complete understanding. ‘Did you, miss? I’ve not seen them, miss.’ He began to look round hopefully. ‘Where did you drop ’em, miss?’

‘I didn’t, Mr. Mipps.’

‘Oh, you didn’t!’ He was completely at sea.

‘No,’ she went on. ‘I said I’d come to see Mr. Scarecrow.’

Thinking that his weather ear had run mad, or that Miss Cicely was confused after her journey, he determined to brazen it out. ‘There now, did you, miss? I didn’t hear you, miss.’

An impersonal voice came from behind the lectern. ‘You seem to be in trouble, Mr. Mipps. Is someone asking for me?’

‘Yessir,’ he gasped. ‘That is – er – no, sir.’ At his wits’ end he finished in a desperate rush – almost in tears: ‘It’s Miss Cicely, sir, she’s come to see Mr. Scarecrow, sir.’ From behind the lectern appeared the benign face of Doctor Syn. ‘Why, Cicely child,’ he said with some surprise, ‘how glad I am to see you back. Mr. Mipps has been telling me of your extraordinary adventures.’

Mr. Mipps, determined not to be brought into it again, and thinking his own adventures quite extraordinary enough, hurried back, for Horace, who at least couldn’t answer back, for Horace, who had been his friend and confidant for many years, was a large black spider that lived in the beam from which Mr. Mipps slung his hammock, waking him each morning by sliding down from this fighting-top to the lower deck of Mr. Mipps’s nose.

Upon seeing Doctor Syn, Cicely uttered a cry of disappointment. ‘Why, ’tis only our dear old Doctor Syn. Then I am too late. How teasing.’ Then upon seeing that the Vicar was looking somewhat hurt, she begged his pardon and told him how glad she was to see him, explaining that the reason for this late return to his house was a pair of gloves which she thought she must have dropped here. ‘Though I must confess I used the missing gloves as an excuse, for I did so want to see the Scarecrow paying you his tithes.’

‘Then you are too late, dear Cicely, and I am equally disappointed, for I hoped that your return here was to let me see you safe and sound.’

‘Oh, but I assure you, I should have come to see you first thing in the morning,’ replied Cicely, adding a little mischievously that she always knew where to find the beloved Vicar, unless, of course, he was out on some errand of mercy, which apparently he had been that night. She supposed it was that poor old Mrs. Wooley again, and vowed she would take her some hot soup in the morning, adding carelessly, ‘how much did the Scarecrow pay?’

Doctor Syn looked at her with not a little curiosity. ‘Why, Cicely,’ he said, ‘what is this sudden interest in such a complicated matter as the payment of tithes?’

She glanced up at him, eyes wide with feigned innocence – and with the suspicion of a smile about the corners of her mouth, answered: ‘Oh, ’tis not a sudden interest. I just wished to see if I am good at reckoning. Was it a large sum?’

Doctor Syn became very vague. ‘Eh, child,’ he said, peering at her through his spectacles. ‘Let me see: well, if I remember what I wrote in the book this time, ’twas a mere trifle.’

At this she seemed to be full of concern, mixed with not a little indignation, saying that she had long suspected that his eyesight was failing, and that he could not have written aright, and she hoped that the Scarecrow wasn’t cheating him, for he had told her most distinctly that tonight’s cargo was a very valuable one.

‘Come, let me see those glasses,’ she said with pretended anxiety. ‘I fear they cannot be strong enough for your poor old eyes,’ as with a deal of motherly care she took them from his nose and looked through them, saying it was just what she had expected and little better than plain glass, and that she would insist upon his going to London with her father the very next time he went to visit his oculist. But for her part, were she his physician she would order him to throw away his years and not to add to them, stressing that without his glasses he might well be old Doctor Syn’s younger brother. ‘No, no, do not move,’ she said, for Doctor Syn was trying to escape her penetrating look and the beruffled hands that firmly held his arms. But for all that, her grip tightened and she continued to gaze, frowning and fussing. ‘Let me look at you more closely. Yes, ’tis true, you are pale. Perhaps ’tis exercise you need. Jogging about on that churchyard pony cannot be good for you. I must ask Papa to give you a more spirited mount, and you must learn to ride. I could teach you.’

Was there a hint of a smile in Doctor Syn’s unbespectacled eyes? Indeed he had no need of them. He saw as well without them as with their protective, ageing screen. He answered quietly: ‘Perhaps Doctor Syn’s younger brother could teach you more things than you have ever dreamt of, Miss Cicely. But I fear that I am not he, and must indeed be failing. ’Tis gracious of you to worry over a poor parson in his dotage. But let us talk of something that interests you more.’

‘Why then,’ she answered very quietly, ‘let us talk of the Scarecrow, for he is the most interesting man I have ever met, if man he be, though I do not really think there is truth in the rumour that he is a ghost. To me, he seemed most real. Aye, and with a heart too, for I felt it beating on the ride from Paris when my horse failed. ’Tis true,’ she went on earnestly, ‘he appears and vanishes like a ghost, for I was swept from the saddle before I felt the horse stumble. But down it went, and I might have gone with it but for a strong arm that certainly did not belong to a spectre.’

The Vicar seemed to be full of perturbed amazement at the dangers she had been through, saying what a terrifying experience it must have been. To which Cicely replied that she hadn’t been frightened at all because of his superb horsemanship, but she had to admit that she had been troubled. The Vicar agreed that it must have been terrible to have been in the arms of such a desperate character.

‘Oh, do not mistake me,’ she protested. ‘I was troubled because I knew ’twas but a few kilometres to the next village, and I would have ridden that way all night. But then, fresh horses, and he vanished again. For the most part he had spoken to me in his rough French, though for that short distance we rode in silence.’ Here her voice took on a new seriousness, and she said as though experiencing it again: ‘And I felt that he knew me, and in some strange way that I had known him all my life. Yes, and that we were being swept on to something more vital than escaping from the mob. Now do you understand why I am troubled?’

The Vicar too seemed as if he wanted to escape. He went to the fire, saying gravely: ‘It seems that this man has taken occasion to be more than a rogue.’

‘Oh, but he is no ordinary adventurer.’ She moved after him and knelt at his feet. ‘Indeed, he is a very wonderful person. You have no idea of his efficiency – his attention to the smallest detail. His daring in running the Revenue blockade made me marvel.’ She turned away from him and looked into the fire. ‘So you see, Doctor Syn, having set myself a riddle, the solution of it makes me very glad.’

‘And have you solved your riddle?’ the Vicar asked quietly.

‘Indeed, without any assistance my heart found the answer.’ She turned and looked earnestly up at him. ‘Dear, kind old Doctor Syn, tell me what I should do, for I am fathoms deep in love with this – pirate.’

Disturbed and shaken at the word she used, he asked urgently: ‘What are you saying? You cannot be serious. A man whose face you’ve never seen.’

‘Oh, I care not what he looks like,’ she cried. ‘In spite of that foolish mask I should love him were he as ugly as sin.’ She was laughing up at him now, and he dared not look at her, but went on protesting that it was madness. That he had a price on his head and was hunted by Army, Navy and Revenue alike.

‘’Twould be madness not to love him,’ she persisted gaily. ‘All the King’s horses and Revenue men cannot stop me.’

Steeling himself to meet that challenging look, he tried desperately to master her compelling eyes, as facing her he said: ‘Then perhaps ’tis foolish of me to try.’ And again, seeking vainly to convince her, asked, ‘Have you stopped to consider that his madness could not be?’

She answered swiftly: ‘I cannot, nor do I desire to stop. My thoughts are his, and if he should command, my life.’ She knelt up straight, which brought her closer to him, and putting one hand upon his arm which rested on the corner of the settle, she looked down at it, toying with the buttons on his coat and teasing said: ‘I shall have no one else if he does not love me. I shall become…’ Here she put her head on one side and thought deeply. ‘Yes,’ she announced, ‘I shall become the spinster of the parish, and devote myself entirely to good works. Maybe I should commence with you. ’Tis true you have no one to look after you.’ She looked down again at that intriguing arm.

‘Why there, what did I say? Your sleeve, you have a button loose. My first good deed shall be to sew it on for you.’

He gently moved the inquisitive hand and rose slowly to his feet, the look of fierce concentration on his face changing to one of calm purpose as he moved away from her. She remained on her knees, sitting back on the heels of her slim riding-boots, fearful yet expectant. Making no haste, he drew off his coat and let it fall. Then deliberately rolling up the right sleeve of his frilled shirt, he moved close to her and gently placed his forearm over the shoulder of the kneeling girl, as though forcing her to look at the tattooed mark upon it. She did not turn her head, but with a caressing movement clasped the incriminating arm to her, and in a small voice asked for needle and thread with which to sew on the offending button. His deep voice was husky as he said, ‘Child, you know that this can never be.’

‘I have always known that it must be,’ she answered, continuing casually, ‘’Twill only be a moment if you have a good spool of black.’

‘But, Cicely, do you realize what this mark is?’

‘’Tis but the picture of a man walking the plank with a shark beneath. I saw it first in Paris upon the arm of a most notorious character,’ and continued just as casually, ‘’Twas foolish of me to leave my thimble behind.’

He fought desperately, reasoning with her against himself, that the tattoo upon his arm was the mark of the pirate Clegg, who should have hung in chains on Execution Dock; that it was the mark of a hunted law-breaker, the mark of a man who ruled the Marsh by fear and with his cunning. But again to this she answered simply:

‘’Tis also the mark of that saintly man the Vicar of Dymchurch, revered by all that know him, and dearly loved by Cicely Cobtree, spinster of the parish, who must remember to carry her chatelaine of pins and thread.’

Though knowing he had already lost, he made a last attempt to save her from what he knew must be inevitable should he allow himself such happiness, so, without mercy, he accused his threefold personality – pirate, smuggler, parson – of being an unholy trinity – and of all the three that saintly parson was but the worst of hypocrites, mouthing his smug sermons and hiding black deeds behind the pillars of the Church. Then turning to her he demanded passionately, ‘How can you love a coward?’

She rose to her feet and stood before him, and fiercely she challenged with a passion equal to his own: ‘Coward in one thing only: you will not say what I await to hear.’

His despair was triumphant as he laughed back at her glorious audacity. ‘Then not even you shall call me a coward,’ he cried, and she was in his arms.

After a little while she sought the answer to another riddle. ‘And how much did the Scarecrow pay?’

‘Eh, child?’ For a moment, and to tease her, he became again the kindly Vicar, then holding her from him at arms’ length he said: ‘All the wealth that was Clegg’s when he sailed the Caribbean would not suffice to pay those tithes. Does that satisfy you?’ She did not answer, but stood content and gazing at him. ‘No?’ But still she did not speak, so he went on: ‘Would you have me sail up London River and loot the Crown Jewels to lay at your feet?’

‘Why, Captain Clegg, should I then be richer than I am?’ she asked. ‘There is now but one thing that I desire.’ He, in his turn, stood silent, looking at her, as she pleaded with a feigned sincerity: ‘Dear, kind old Doctor Syn, pray stop preaching your horrid sermons against my beloved Scarecrow.’

He laughed again and drew her swiftly to him. For Christopher Syn had remembered to forget the pirate’s slogan – no petticoats aboard.

And so it was that the next morning Doctor Syn, happening to perceive from his study window a last remaining rose upon his favourite tree, went out to pick it, and there upon the frosty ground beneath this lovely challenge to the winter was a pair of gauntlet gloves.

Chapter 13

In which Mr. Mipps Discovers an Old Friend and Doctor Syn Discovers a Secret

Doctor Syn smiled and promised Cicely that although he could not stop preaching against this rascal, he would at least modify his righteous rage, adding in a more serious tone that perhaps in the near future it might not be necessary to preach upon that vein at all, since already it was evident that the Scarecrow was showing signs of repentance, and that he, as shepherd of the flock, hoped that he might be able to lead one more stray lamb into the fold. So for the third time that evening Cicely crossed the Glebe field, but this time in company with Doctor Syn. Upon reaching the Court House, she was loth to part with him so soon, and entreated him to come in, urging that having found him she never wanted to let him go, and she also knew by the look in Papa’s eye that he too was in need of moral support.

To this Doctor Syn replied that the house would sure to be in great commotion over their sudden return, and that her mother and Aunt Agatha would want to welcome their stray lambs home, in true feminine manner. Cicely answered, smiling somewhat ruefully, that in truth she knew wwell what that meant: a deal of fussings, scoldings, twitterings and floods of tears, so that she, in trying to be a dutiful daughter, would be hard put to it to squeeze out one, so happy was she, and since by his presence their enjoyment at a thorough good cry at the family reunion would have to be somewhat modified, pray, would he not come in and help her out? But he was still firm and taking her in his arms kissed her tenderly good night, vowing that he would visit them the next morning. As a final farewell Cicely whispered: ‘’Tis very sad that poor old Doctor Syn is in his dotage. I do hope the dear old gentleman will not be jealous of his younger brother, for in truth I am fathoms deep in love with that – unholy trinity.’

And she was gone, laughing back at him as she ran lightly across the flagstoned hall. Stopping at the steps, she turned, jerking her head in the direction of the drawing-room upstairs, whence came a babble of excited voices and a sound that meant only one thing – Maria was thoroughly enjoying herself again. With a gesture of comical despair, and an expression which said, ‘There now, what did I tell you?’ she allowed her happiness to express itself in the most curious, charming manner. Delicately lifting the skirt of her riding-habit, as if about to sweep him a curtsey, she suddenly executed a quaint, high-spirited little jig. Then, with a further gesture of humourous resignation, she waved to him and stumped off up the stairs.

He had watched her, enchanted, and stood for a while after she had gone, smiling at the thought of her lovely youthful grace, and he made a vow that he would sacrifice all rather than hurt a hair of her head.

Closing the front door, he looked up to the stars, stretching himself as though to reach and thank them, and breathed a vast deep sigh.

Then he strode off down the village street. So light was his step, so high his head and heart, that had any man seen him they might well have thought, ‘Here must be the younger brother of the man we know,’ and, indeed, he was not following Doctor Syn’s usual habit of returning to the Vicarage before setting out upon one of his nightly expeditions. He certainly was not in the mood, this night, for the joggings of his churchyard pony. He laughed alooud when thinking again of her audacious offer to teach him to ride, and a great longing seized him to let the world know who he was and the things that he could do. And thus exalted, he left the village and strode out across the Marsh.

Some twenty minutes later he reached the loneliest spot – a small dilapidated cottage that the Marsh-folk shunned, for in their seafaring, superstitious minds they feared the old woman who lived there, believing her to be a witch and in the Devil’s pay. In the eyes of these simple folk Doctor Syn became the more respected because he did not fear to visit her. But then the Vicar was such a very holy man.

Upon this night he was not the only one who had the courage to enter Mother Handaway’s abode, for three others were there before him.

The fact that it was avoided by all God-fearing folk, and by reason of its lonely situation, cut off by intersecting dykes whose dilapidated bridges were unsafe, gave this poor hovel a value to anyone who wished to work in secret. For many years it had served the Scarecrow well, for in a dry dyke close to the house was a well-built, underground stable, dating, some said, from the days of the Roman occupation. Its roof was the natural pasture soil and its only door was hidden beneath a stack of drying bullrushes. The inside was commodious and dry, owing to the excellent drainage system of the builders in those ancient times.

With these advantages, therefore, it was an admirable hiding-place for the Scarecrow’s wild, black horse, Gehenna, and used as well by another gentleman whose way of business demanded secrecy. Gentleman James sheltered there when a hue-and-cry was at its height, or when the Scarecrow wished him to ride as deputy. In this way the Authorities had been fooled many times, for having seen the Scarecrow in one part of the Marsh, dumbfounded Dragoons or Preventive men, discussing their experiences the next day, would discover that this fearsome creature had also appeared some miles away at that particular time, and the rumour had grown that the Scarecrow was in truth a demon. So it appeared almost natural for this terrifying, unearthly horseman to disappear in the vicinity of this haunted spot. The smugglers took full advantage of the old woman’s fearsome reputation, and saw that it was enhanced by weird shriekings in the night and oily smoke rising from the chimney-stack, thus giving encouragement to many a gruesome tale about the old woman’s secret practices. The old hag’s appearance was enough to quell the stoutest heart. Sharp curved nose and pointed chin guarded her one-toothed, mumbling mouth. Her evil eyes were beady and protected by straggly brows that matched the grey beard upon her chin. Her hair hung in long rats’ tails, and her gnarled fingers made her hands look like claws. Half crazed, she too believed herself the witch of popular belief, for had she not conjured up the Devil in the likeness of that holy man, the Vicar of Dymchurch? And did not the Devil pay her more golden guineas than a poor parson could ever afford?

Upon this night she sat in a corner by the fire surrounded by her clawing cats, huddled and mumbling to herself, while round a table, seated on barrels, talking and drinking, were three men.

Heaped into a pile in front of Jimmie Bone was a various assortment of the kind of trinkets that delight a feminine heart. It waas the Highwayman’s habit to keep in reserve a goodly selection of such baubles, and he took great care always to have some about him as a reward for services rendered. Though as a rule these gifts were bestowed carelessly enough, upon this occasion Mr. Bone did not seem able to make up his mind. He scratched his head, took up a ring, only to put it back in favour of a brooch or bracelet, and then thumping the table which made the whole heap jump, he cried out in his perplexity: ‘S’death, I cannot tell which one would suit her best.’

The other two looked up, surprised from their earnest conversation.

‘Why, what troubles you, Jimmie?’ asked Mr. Mipps. ‘Can’t you find one to your likin’? Seems to me that a wench should be well-pleased with any of ’em. Who’s it for? That new one at the Red Lion in Hythe, I’ll be bound. Now bein’ a sandy-’aired, I should suggest a garnet, or isn’t it ’er? If you describes ’er we might be able to assist. Pedro ’ere will give you first-rate information. ’Ad to leave Spain, he did; too many señoritas wanted to call him Papa, didn’t they, me old flirt-man?’

‘No, no, my excellent Mipps,’ protested Pedro, in laboured English. ‘The señoritas wish me to call on their Papa.’

‘Means the same thing in the end, don’t it, you old Spanish bullfight? Anyway,’ he went on to Jimmie Bone, ‘what he don’t know about what they want ain’t worth tellin’ to your auntie. So come, give us a look at her riggin’ and we’ll tell you ’ow to deck her figure’ead.’

The little Spanish sea-captain tugged excitedly at his beard, his black eyes dancing at the thought of hearing a description from Señor Bone of the girl who was lucky enough to please him. His weatherbeaten little face, tanned to old leather and having indeed the same texture, wrinkled into a mesh of smiling expectancy. He turned his grizzled head this way and that, which made the golden rings in his ears flash in the light. He spoke with the knowledge of an expert: ‘I know, I know, before you start, I know. She is like the peach against the wall ready for the – ’ow you say? – ah, the pluckings.’

Mr. Bone had other ideas on the subject, though he seemed as unable to describe the lady as he had been to select her present. After much humming and ha-ing and entreating them not to laugh at him, he confessed that although the lady in question was sparkling, witty and full of charm, he didn’t know what colour her hair was as she wore the most enormous white wig, and that she stood no higher than the tip of his horse’s nose, had a face like a bright little robin, was unmarried and well-nigh eighty.

‘Well, blow me down and knock me up!’ cried Mipps. ‘If that ain’t Miss Agatha Gordon at Squire’s, I’ll keel-haul myself.’

‘That’s the party,’ cried Mr. Bone. ‘As nice a little old lady as ever I robbed. But I’ve give back her jewels and I want to apologize with a keepsake.’

Captain Pedro was too bewildered to speak. He could not understand how it was that so fine a caballero as this highwayman should be heart-troubled by an old lady of eighty. Like all foreigners, he knew, of course, that all Englishmen are mad, but he had not imagined anyone being as strange as this. He was hoping to hear more upon the matter when the door opened and Doctor Syn stood looking at them.

The effect on Mother Handaway was remarkable. She stretched out her scraggy arms straight before her with finger turned up and palms towards her master as though to ward off any curse he might think to hurl at her. By her averted frightened eyes, and lips that muttered invocations, the three men at the table knew that the old hag was in the grip of fear, waiting to hear whether the inscrutable black-clothed figure was angy with her.

He did not keep her long in this awful suspense. Though he had walked the Marsh, his soul had still been singing with the stars, and he could not find it in his heart to enjoy the power he exercised over this misguided creature, so in a quiet calm voice he said: ‘You have done well, old mother, and shall be well repaid. Go to the stables, and light the lanterns there.’

After uttering a wild cry of joy, she fell forward in ecstasy of genuflexions, and when she heard another kindly order – ‘Go. There, there.

All’s well’ – she chuckled in delight and, followed by the cats about her, hobbled past him through the door.

Quickly Doctor Syn closed the door behind her and with a smile of real affection lighting up his eyes went over to the table from which the three men had risen.

‘’Tis good to see you, Pedro,’ and he took the Spanish captain’s hands in both of his. ‘You managed the last business so well and with such care for the valuable cargo in those barrels – oh yes, I have heard how gently they were handled – that I am reluctant to send you back again so soon to France. Mipps will have told you that there are two prisoners to be taken to our harbour in the Somme, and there is no one who can slip through the blockade like our Pedro —’

The gratified Pedro interrupted with an emphatic: ‘Ah no, my Captain, there is you. There were moments when the good Greyhound slid before the wind and first the French and then the English battleships let drive at her that Pedro thought, “What will the Captain do now? Will he tack here or there? Hold his fire or answer them?” Ah yes – your Pedro needed you. But your luck held with me – and home we got.’

‘Would that I could have been with you, Pedro,’ said Doctor Syn. ‘The call of the sea remains as strong as ever. You did well, my friend. Was the cargo – troublesome? I got your message.’

‘Ah – the bookmarks. ’Tis good, our system of the post at the bookshop. I would I wrote such good letters as our young boy Jacques. I speak – he write, and he deliver it.’ Thumping himself on the chest, he spat out in disgust: ‘Bah – Pedro! Unlettered, ignorant Spanish pig. Bah!’

‘You have a good deal of courage which makes up for your lack of letters, my good little Pedro.’

‘Just as my weather ear makes up for me lack of inches, eh?’ said Mr. Mipps meaningly. Then, seeing that the others had not understood, except, of course, the Vicar, Mipps explained: ‘Another of the Captain’s little jokes. Gentleman James is lucky. Can’t be called a dwarf. Though I wouldn’t mind so much being a little man and someone was to put me in a barrel – full one, mind you, not empty. And that reminds me, talkin’ of barrels. Had a message from Vulture. Them coopered Dragoons got to Sandgate lovely. Says he popped them other two you didn’t want to ride over the Marsh with into barrels as well. Oh, and he found two more lurkin’ about he didn’t like, to which he did ditto, just to make up the nice round half-dozen for Mr. Hyde. Left ’em in a row on the doorstep. I’d like to give my weather eye a treat when he opens ’em. You’re askin for trouble with Mr. Hyde. He’ll be Mr. Seek now.’

At which they laughed heartily. ‘Ah,’ cried Pedro. ‘I do not think his cargo please him as mine please me. At least, the half of it. That miss – a brave one. Rough or smooth – all same to her. When all was well and as you told me, Captain, I let them out between the decks. The tall one – she clapped me on the back and say, “Good Pedro. Why did you not let me out before? I heard the guns, I could have helped you man them.” But the little one’ – the thought made Pedro hold up his hands and flap them in disgust. ‘She scream at me as though it were my fault. She say, “You let me out. You stop the boat and let me off.” Had it not been for orders, Pedro might well have say, “Go then, miss. The water, it is deep and wet, but if you wish, ’op it.” Alles. Pouf!’ The noise conveyed what he meant. That he was extremely glad to be rid of her.

Doctor Syn looked at his fob watch, and said it was some ten minutes short of midnight and time to be saddling up.

‘You will ride with Mipps to the beach, Pedro,’ he said, ‘and the luggers will take you off during the run, and put you aboard the Greyhound. She’s off Dungeness, is she not? Mipps, saddle Gehenna now, while I have word with James here.’

Mipps nodded, and with an ‘Aye-aye, sir,’ took Pedro by the arm and the two little men went off together, their back views very similar.

‘Well, Jimmie, what news?’ asked Doctor Syn as they went to the fire and sat down in the chimney-seat.

‘If it’s personal news you mean, then James ain’t got much to tell you, for them bloody red-robins – beg pardon, Vicar – them nice Bow Street Runners, is remarkably quiet. Expectin’ them to jump any time now, so if you don’t hear from me you’ll know I’m taking my vacation at Slippery’s this time. The false run went off according to plan. “British Grenadiers”, eh? I made the Dragoons dance to a different tune. “Over the Border Away, Away.” I took ’em across the Kent Ditch and got ’em lost in Sussex. “Well and truly lost”, you said, and well and truly lost they are. We turned the signposts, so if they do happen to get out they’ll go trotting back into Sussex again.’