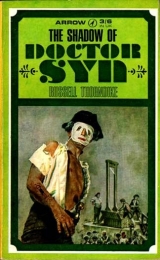

Текст книги "The Shadow of Dr Syn"

Автор книги: Russell Thorndike

Жанр:

Исторические приключения

сообщить о нарушении

Текущая страница: 5 (всего у книги 16 страниц)

‘Oh, Mr. Mipps,’ she cried, throwing her arms about him and well-nigh suffocating the bewildered little Sexton, ‘never so pleased to see you. Oh, what a fright I had. Never thought I’d get here. Comin’ round the corner, thought I’d see the usual – but hangin’ in the Court Yard – glad it didn’t chase me. Can I have a brandy?’

From the hidden regions of her capacious bosom, the muffled voice of the Sexton plaintively appealed to be ‘let go of’, and extricating himself with difficulty, gasped out in his turn, ‘Careful now, don’t be so print.1 Too early for canoodlin’. Can you ’ave a brandy? Phew! Need one myself after all that. ’Ere you are then. Take a nip and tell me why you’ve got the dawthers,’ and producing a heavy flask from an inside pocket, he handed it to the grateful housekeeper.

Mrs. Honeyballs took a generous pull, sighed loudly, and sat down. She then prepared to enjoy and freshly horrify herself with a description of what she had seen, but was disappointed when Mr. Mipps, dismissing the subject, remarked ‘Oh, thought you’d seen something ’orrid. What’s a corpse before breakfast? Undertakers ’as to live, don’t they? He’ll be buried in the parish, and them Lords of the Level allows me a god price. ’Ave to flip round there and measure him up after I’ve cleaned out the font for the christening. Funny

– I was only sayin’ yesterday that while waitin’ for old Mrs Wooley to make up her mind I could do with another corpse with brass ’andles.’ At which Mrs. Honeyballs, somewhat disgruntled, seized mop and bucket and set to work, noisily relieving her frustrated feelings, until Mr. Mipps was forced to tell her to ’ush her bucket as the poor dear Vicar, after his long journey, didn’t ought to be disturbed. Leaving her, certainly hushed though still resentful, he took himself off to the church, making mental notes while passing the cause of Mrs. Honeyballs’ discomfiture as to the length and type of coffin it might need. Thus happily engaged upon his funereal but lucrative speculation, he started to clean out the font.

His enthusiasm, however, was not shared by the Squire of Dymchurch, who, irritated by ‘a confounded babble goin’ on beneath his bedroom window so early in the mornin’, damme’ – pulled back the curtains to see the cause of it. The sight of half the village ‘gawpin’’ at a corpse he hadn’t convicted hanging from his official gibbet threw him into one of his before-breakfast rages, which, this morning, however, was perfectly justifiable.

Sir Antony Cobtree, though taking his position as Chief Magistrate and Leveller of Marsh Scotts very seriously, at heart preferred the more pleasant occupation of a country squire, to wit, his horses and his dogs; and indeed his favourite pastime was followin’ hounds. So upon recollecting that he had promised himself a day’s relaxation away from his extra duties as a family man, for ‘them prattlin’ women’ were getting on his nerves ‘in the most deuced fashion’, he was deeply chagrined that an uncalled intrudin’ corpse would necessitate his presence in that ‘stinkin’ Court Room’ to preside over an Inquiry, thereby ‘ruinin’ a good day’s sport, damme’.

1 Bright.

Tugging at every bell-pull in his bed-chamber to no avail, almost crying with vexation, he trotted out upon the landing in search of another. He had just viewed one at the far end of the long gallery and was in full pursuit, when, tripping over his flapping nightshirt, he slid the whole length of the highly polished floor and reached it quicker than he had anticipated. His carpet slippers and a Persian rug flying from beneath him, bobbled night-cap obscuring his vision, he clutched despairingly at the bell-pull, which, unable to stand up to the full weight of the Squire, broke with snapping wires and clattered about his head, as he came down heavily upon that part of his person most pertinent to his saddle. There he sat for a considerable time before regaining sufficient breath to enable him to give vent to as many good round oaths as he could remember, and it was from this lowly position, where he had thoroughly damned beeswax and bell-pulls, that he espied upon the top of a tallboy a hunting-horn. Hope returned upon the sight of this familiar object, with which he knew he could give tongue. Having achieved possession of this he threw restraint to the winds and all his lung power into the blowing of a long series of ‘View Holloas’. This unorthodox method of calling for attention had the desired effect. He immediately became the centre of interest. Doors flew open all along the gallery. Housemaids peeped out and jumped back, thinking the Squire had run mad, while her ladyship came out in déshabillé and high dudgeon and admonished him for drinking so early in the morning, and what would Aunt Agatha think.

As a matter of fact Aunt Agatha’s thoughts were of the pleasantest nature, for this same noise had awakened in her happy memories of the hunting-field, and having told Lisette to open the door to enable her to hear the better, Mister Pitt, attracted by this rallying call, slipped unnoted from the room, and set out on a trail of investigation. Coming from the East Wing, he followed the dictation of his nose and ears till he reached the opposite end of the Long Gallery, where his dog’s-eye view was of two curiously attired humans, the lady soundly rating the gentleman, who like a naughty boy was standing dumb before her. An inviting length of dressing-gown cord trailing on the floor behind him enticed Mister Pitt to creep nearer, and when the Squire, unable to tolerate this nagging further, put the hunting-horn to his lips and deliberately emitted one short crude noise in protest, the poodle’s curiosity knew no bounds. As in answer to the Squire, he barked a high-pitched ‘Tally-ho’ and charged, but met with the same difficulties, for with jingling paws and legs splayed out, he came skating towards the unsuspecting gentleman. Such uncontrollable velocity surprised Mister Pitt into biting the first thing that came into contact with his nose. This happened to be the Squire’s big toe, and to make matters worse was the one that had been most damnably pinched by a ‘tight huntin’-boot’. The scene that ensued was indescribable, since the Squire’s language was so strong that it sent Lady Caroline, hands over ears, scurrying back to her room, where, after slamming the door, she succumbed to a fit of the flutters, while the irate gentleman, his tone at once persuasive and abusive, with such entreaties as ‘Nice leetle doggie – let go – get away from me, you little brute,’ at last succeeded in kicking loose and, making for cover, dashing towards his bedroom; while Mister Pitt, having, like a tiger, tasted blood, kept up lightning attacks upon the succulent retreating ankles. But surprisingly enough the Squire was too quick for him, and his nose came into violent contact with something that he could not bite – a slamming door, behind which the Squire had gone to ground.

Within his room Sir Antony’s annoyance by no means abated, when he heard that the commotion outside the house had grown louder and he went straight to the window and flung it wide, intending to harangue the crowd. Having lost his dignity with Mister Pitt, he quite forgot to assume it again for the villagers, and indeed upon seeing his own lackey, Thomas, in the front row of the corpse’s audience, with his arm round a giggling housemaid, he so far forgot himself as to lean perilously far out over the sill, thus endangering not only his person, but his still precariously tilted night-cap.

Mixing hunting phrases with official language he soon succeeded in sending the villagers about their business, and the errant Thomas, crimson to the ears, was ordered to attend on his master immediately.

Having somewhat mollified his feelings, he was yet fully aware that he was certaily in for a ‘damned dull, deucedly aggravatin’ day, findin’ out the identity of this impertinent corpse and probin’ the pros and cons, to say nothing of Caroline’s tantrums ’cos of what he’d done on the trumpet, while me wife’s Aunt Agatha will be accusin’ me of ill-treatin’ that snappin’, yappin’, doormat of a dog’. Apart from these trifling but upsetting irritations, there was the sincere anxiety about his daughters: Maria, married to a Frenchman in Paris, with the Terror raging, and Cicely having disappeared without a word. Thanking God that Doctor Syn was back again from London, Sir Antony Cobtree at least promised himself a pleasant evening. So, cheered by this prospect, he determined to make sure of it, and crossing to his escritoire he sat down and penned without any further ado the following – noting as he wrote the date that thirteen never had been his lucky number.

Nov. 13 th . The Court House, Dymchurch.

My Dear Christopher,

I hear from me wife’s Aunt Agatha that you are returned from London for which Heaven be praised. I shall be infernally busy all day, at the Court House. The reason of this you will know by now, and I’ll wager it’s the Scarecrow’s work. Since morning and afternoon are like to prove irritating (and to say truth, I cannot abide them prattlin’ women no longer), I intended dining with you tonight at the Vicarage where we shall be free of ’em. I will send over by hand of Thomas as much wine as I think we can conveniently consume, for I find myself in a mood to forget my troubles in the arms of Bacchus, and I have but recently opened a very special bin which I think will be to your taste, so have the goodness my dear fellow to postpone whatever else you might have thought to do, let the parish go hang for once and forgive me for thus inviting myself but I have the necessity to see you.

Affect. Yours, Tony.

Which somewhat unscholarly letter made Doctor Syn smile, when within the hour it was handed to him with his morning chocolate. He thought affectionately of this great warm-hearted overgrown schoolboy. Dear old Tony had not altered one iota since the far-off days when they had been fellow students together at Queen’s College, Oxford. In fact Tony was unalterable, living out the same heritage as his ancestors before him. His world was bounded by London and Romney Marsh, for with typical insularity he had never asked for more, content to belong to that solid support of the country classed landed English gentry. Christopher knew himself to be entirely opposite – the type of Englishman who has to see the far, waste places of the world. And he fell to thinking what this simple old friend of his would think should he ever discover what manner of life his old College friend had lived or what he would do should he ever learn the truth.

His reverie was broken by Mr. Mipps coming in to his room for the so-called parochial orders of the day. ‘There now,’ he exclaimed upon seeing the Vicar’s untasted chocolate, ‘what did I say to Mrs. Honeyballs? “Mrs. Honeyballs,” I says, “’ush your bucket and don’t disturb the Vicar after his long tedious journey”,’ whereupon Mr. Mipps favoured the Vicar with a slow wink, whisked away the cold chocolate, moved two books from the shelf beside the bed, thus disclosing a neatly concealed bottle of brandy, remarking to the Vicar, ‘Now ’ere is something that will do you good after a tirin’ journey. What a ride it was! Oh, did you ’ave a good night? I do ’ope you weren’t disturbed with all them goings on. Village is fair buzzin’ with it all. Oh, and of course, you don’t know the latest news. There’s a nice new corpse ’angin’ on the gibbet. Scarecrow again, they says. Have to be careful, you know, sir – “preachin’” all them sermons against him. He’s gettin’ a bit above hisself. Shouldn’t be surprised if he didn’t try and get you and me next. Wouldn’t we look ernful on a broadsheet? Vicar and Sexton found dangling together.’ Which last remark sent Mr. Mipps into uncontrollable giggles resulting in a fit of the hiccups, so that Doctor Syn had to pass the brandy-bottle for his relief. Which in truth was exactly what Mipps meant him to do.

‘When you have recovered, Mr. Mipps, perhaps you will pass me back the bottle and discuss parochial affairs.’

‘Yes, sir – hic – parochial affairs. Real parochial affairs – or er?’

‘Yes, Mr. Mipps, we’ll discuss that too.’

‘Oh – that’s what I wanted to know. First of all – it’s them “British Grenadiers” again today followed by “The Girl I Left Behind Me”. The word is bein’ passed as usual. Coaches playin’ ’em both voyages, up and down. Next, please? Oh, Jimmie Bone – messages from him this mornin’ – says he forgot to ask you last night – if you’ll be needing him to ride as the Scarecrow for you tonight.’

‘Tell him to stand by till we know which way the cat’s goin’ to jump.’

‘Oh, don’t we know? Suppose we don’t. Oh, talking of cats. That there Revenue man. Been seen prowlin’ through Hythe. Ought to be here any minute now. Oh, talkin’ of Hythe: ’ere’s a bit o’ news. Mrs. Waggetts’ cousin twice removed has to go into Hythe on account of what she’s expectin’ grantiddlers.1 She runs into her uncle, who has with him a relation of the bootboy at the “Red Lion”.’

Doctor Syn interrupted. ‘I trust the news is not so involved as the relationships.’

Mipps replied promptly: ‘No, sir. Gets clearer. Well, I’ll tell you. That there Foulkes. Now what worried the boot-boy was that he hadn’t got no boots. Wasn’t half in a dobbin2 about it too. Rantin’ and roarin’. Foulkes I mean, not the boot-boy. Sends out for cobblers and shoemakers. “Red Lion” in a uproar. But by the time he’s measured the whole place knows what he’s come for. But here’s the best bit of news, sir. He’s passin’ the word and says he wants it passed that he’ll challenge the Scarecrow in open duel. Quite positive he’ll win, too. Says he’ll wager a thousand with anyone.’

‘That’s very interesting, Mr. Mipps,’ replied Doctor Syn. ‘He’s killed some dozen men already. I wonder what the Scarecrow will do about that?’

‘Yes – that’s just what I was wondering of, too.’

‘I shouldn’t let it worry you, Mr. Mipps. Yes, the Sluice Gates. Oh – let me see, high tide? Well, well. Now the christening; this afternoon, of course. Remember?’

1 Grandchildren.

2 Temper.

Mipps nodded. ‘Just cleaned out the font. Ever looked down from the top of them Sluice Gates?’

The Vicar nodded.

Mipps went on. ‘A lot of lovely mud goes swirlin’ round. Thin mud.

’Orrid mud.’

‘Yes, Mr. Mipps, I have noticed that there is mud in the Sluice Gates. And oh, by the way, Mr. Mipps, the Squire is dining with me tonight. Would you be so kind as to inform Mrs. Honeyballs to make an especial effort. I thought perhaps some few dozen oysters, that brace of pheasants, a little soufflé….’

But to this Mipps objected, ‘Oh, shouldn’t trust her with a soufflé. Not today. Got the dawthers, she’s all of a shake. That corpse made her shake good and peart,1 and when Mrs. Honeyballs shakes – she shakes, and you don’t want a shaky pudding. Better make it a trifle. Won’t matter then if she is heavy-handed. By the way, sir, you was talkin’ of Pedro – will he be comin’ over tonight, sir?’

Doctor Syn nodded. ‘Yes, Mr. Mipps, with the usual cargo, if all goes well. And I have instructed Pedro that all must go well this time. But he’s a good man; I’d trust him where I’d trust few others. Now, Mr. Mipps, ’tis time for me to rise. I have a sermon to prepare and must balance up the Tithe Book. And I must not forget to do that little errand for Jimmie Bone, though I think it would be well to wait for a day or so until the hue and cry for him dies down. I shall return the jewels to Miss Gordon personally. You know, Mipps, Gentleman James has got discernment, for the old lady certainly has character. I have a great liking for the Scots.’ So saying, Doctor Syn got out of bed, went to the open window and stood for a while scrutinizing sea and sky as if reviewing the weather, while Mr. Mipps watched him in this familiar attitude, as though he were upon the aft-deck of his old ship Imogene, looking for dangers on the seas ahead. He wished they could both hoist canvas and sail the seas again. So, stifling a sigh of longing and regret, he went down to execute his master’s orders.

An hour or so later Doctor Syn was busily engaged upon parochial accounts in the library, when Mr. Mipps disturbed him again with, ‘Beg pardon, sir, he’s ’ere again. That there Will-Jill. Looking a bit subdued like – not that I don’t wonder – but he’s ever so pleasant – and asked most polite to see you. The fright you give him must have done him good. Oh, beg your pardon, sir,’ this upon noticing the Vicar’s warning look. ‘Shall I show him in, sir?’

1 Lively.

‘Yes, indeed, Mr. Mipps. I shall be delighted to make his acquaintance. I somehow thought that he might pay me a visit.’

And so Lord Cullingford, tired, yet with a new look of determination, entered the library and introduced himself to the Vicar.

‘I must ask your pardon, sir,’ he said, ‘for thrusting myself upon you like this, uninvited, but I did not wish to return to London without fulfilling the idea with which I set out. The reason of my visit this morning, however, differs from my original intention. I came now, sir, simply to pay my respect. Happening to be at Crockford’s on the night when you confronted a certain gentleman of my acquaintance, I vowed that I would come to you for assistance, for I had set myself what I now know to be a herculean task – to catch or kill the Scarecrow. Oh, pray do not laugh at me, sir,’ for Doctor Syn was regarding him with a kindly quizzical air, ‘for I was in dire distress and most damnably in need of the Government reward.’ He plunged into a full description of allthat had happened to him since he left the Ship Inn with the Dragoons, ending up with the strange appeal that Doctor Syn should not judge the Scarecrow too harshly, ‘for, reverend sir, he must be a good man at heart. True, I saw him condemn a man to death as I told you, but it was justifiable according to the code – why, the Forces of the Crown would do the same. Yet what officer of the Crown would take the pains to show a foolish young man how best to prove himself, and become a tolerable good citizen?’ He then explained in the simplest manner that he was going to take the Scarecrow’s advice by avoiding his extravagant friends, and joining up with men who had to earn a living – in short, the Army. ‘For though I have but a few guineas left in my pocket,’ he said, ‘I have at least gained something of great value – my self-respect, and I shall ever be grateful to this strange, incalculable being that people call the Scarecrow.’

Doctor Syn had listened to this frank confession with mixed feelings – sympathy for the misguided but engaging lad who might indeed have been his own son, and admiration for the purpose he displayed, and was thankful that he had indeed been able to effect this transformation. Humbled a little by the knowledge of his own secret life, he determined to help this youngster further. So with the greatest tact he persuaded Lord Cullingham to accept a loan of some few hundred guineas, laughingly telling him that there was life in the old Vicar yet, and as he was liable to be here for a number of years, would be delighted to see him whenever his lordship cared to call.

So half an hour later Aunt Agatha, having taken Lisette to see the wonders of the sea-wall of Marsh, passed a young man coming from the direction of the Vicarage, who raised his hat with a flourish and gave them a sweeping bow. She remarked to her maid that he must be in very good spirits for she never did see such a well-set-up young man, adding however that as men went, she still had a penchant for that naughty highwayman. She was further reminded of the said gentleman when, upon walking slowly back through the village, MisterPitt making almost as complete an investigation of it as Mrs. Honeyballs, the local coach went by in great style, horn blowing gaily. But Aunt Agatha’s musical ear was slightly confused, for though the tune it played was undoubtedly ‘those same dratted Grenadiers’, it somehow merged into one of her own Scottish songs – a popular Jacobite air.

Descending the grand staircase on her way down to luncheon, she remarked to Lady Caroline that she was in good appetite, having thoroughly enjoyed her morning perambulation, but it amazed her to observe that, though having such bracing air, Dymchurch seemed a very sleepy place in the daytime, and she hoped that Sir Antony’s tenants were not keeping late hours.

Then, strangely enough, as she passed into the dining-room, she found herself humming, quite loudly, that lively tune, ‘The Girl I Left Behind Me’.

Chapter 8

The Squire Sums Up

Sir Antony’s worst fears were justified. His day was ‘decidedly aggravatin’.’ To begin with, no sooner had he finished his breakfast when old Doctor Sennacherib Pepper was announced, and he was forced to go and watch the inquest. ‘Most unhealthy, probin’ about a corpse just after a meal – enough to make a feller’s cold grouse freeze inside him’; which it did later, having eaten so quickly, thereby giving him a bad attack of his usuals. But on leaving the mortuary to be rid of the nauseating sight, he had bumped into a fat constable, and ‘the great clumpin’ creature’ had trodden clumsily upon his throbbing toe, which so pained him for the rest of the morning that he was compelled to loosen the buckle of his shoe, surreptitiously easing it off beneath his robes, so that when the court rose for the luncheon recess, and he pompously led the procession down the stairs, it was not until he trod upon a coffin-nail that he realized he was without it; and so, in a most undignified manner, he had to scamper back up the stairs. Retrieving the offending shoe with difficulty, he bumped his head against the reading-desk, which knocked his judge’s wig askew, and since, by this time, things had gone too far and he had not bothered to put it straight, he knew, by the ‘disapprovin’’ look on her ladyship’s face, that she thought he had been at it again. Stifling a desier to do naturally what he had done that morning with the aid of a hunting-horn, he tried to enjoy his food, but Sennacherib Pepper, whom he had purposely placed at the far end of the table, kept shouting details of his grisly trade, which ‘me wife’s Aunt Agatha’, who sat beside him, kept ‘hummin’’ that maddenin’ tune, that all the village seemed to have been at that mornin’. Indeed, upon whistling it himself that afternoon, he had not been able to understand why he was looked at by several in the Court in such a peculiar manner. The fact was that they did not understand why the Chief Magistrate was in truth passing the smugglers’ signal for that very night. Blissfully innocent of this, however, he continued with the proceedings. After lengthy weighing of the pros and cons, during which he became painfully aware that his seat of jurisdiction had been badly bruised beneath that confounded bell-pull, the jury at last managed to agree upon one point, that the corpse in question was the remains of one Gabriel Creach which everyone had known in the beginning. Indeed, everyone having known him for years, the whole thing was, therefore, a shocking waste of time.

Well – there it was. He had been hanged by the neck until he was dead, by some person or persons unknown – to wit – the Scarecrow, which the jury found on one was able to do anything about, since the Army, the Navy, the Revernue and Bow Street Runners, to say nothing of private enterprise, had all been after him for years and failed to catch this notorious malefactor.

Sir Anthony Cobtree, in his summing-up, found there was so little to say upon the subject, that he had to try and spin things out, to make it sound better, and becoming thus gravelled for lack of matter, he discovered that in order to make some sort of impression, he had, after a lengthy, pompous oration, involved himself most damnably. In order to get out of this difficulty with what little dignity he had left, he had, therefore, quite without meaning it, pledged himself to a further thousand guineas, out of his own purse, over and above the Government’s proclaimed reward, ‘to any who shall rid us of this

– er – this um – this thorn in our – um’ (fumbling for the word that had escaped him, a twinge from his bruise gave him his cue) ‘in our seat of um-er. Oh, well, anyway, in my seat of errum – of JUSTICE. I mean – this botherin’ nuisance.’ Finishing thus lamely, he sat down cautiously, perspiring freely and none too happy as to what Caroline would say to him for having so willfully mortgaged her pin-money. He was, therefore, agreeably surprised when the whole Court rose and cheered him for a ‘jolly good fellow. Long live the Squire’. Villagers and jury alike, equally surprised that for once their Squire had done more than was expected of him, applauded him vigorously for thus turning what had been a thoroughly dismal and boring affair into a cause for jollification.

Gratified at the enthusiasm of his tenants, and pleasantly conscious that his personal success had put that ‘dratted corpse in the shade’, his departure from the Court House was like a triumphal progress, as amid loud cheerings, surrounded by bobbing villagers he followed the Sword of Justice borne by the Clerk of the Court out into the street. Here Sir Anthony, now thoroughly swollen-headed, was easily prevailed upon to repair to the Ship Inn for refreshment.

And so some two hours later, slightly dishevelled and smelling most strongly of the public bar, judicial wig over one ear and official robes looped high for convenience, he burst into the boudoir of his astonished lady wife, and, knowing that the best method of defence is attack pursed his lips, and loudly did what he had longed to do all day. Then he told her ladyship in no mean language that this time he had really been at it.

The Dymchurch beadle came in for a little of the Squire’s reflected glory, for at the Ship Inn, Sir Antony, after several of Mrs. Waggets’ specials, decided to have his Proclamation sent out there and then. So he and the Beadle had, between the rapid succession of rounds, written and solemnly rehearsed it together. This entailed a deal of serious thinking and was indeed thirsty work, so that before setting out on his rounds of the village the Beadle had had so many rounds with Sir Antony that his condition was pleasantly mellow.

Armed with bell, lantern and parchment he set off up the street to the Court House Square. Using the Squire’s mounting-block for his pulpit, and much pomp and ceremony and many ringings of his large hand-bell, he commenced. His voice, well lubricated with good strong ale, intoned the familiar ‘Oyez! Oyez! Oyez!’ which caused Sir Antony, who was dressing for dinner, to open his bedroom window and wave to him in brotherly greeting while shouting encouraging remarks. The Beadle waved back, and after several false starts began.

‘Sir Antony Cobtree, Chief Magistrate and Leveller of Marsh Scotts, deeming it meet and right, does out of his personal privy purse offer 1000 guineas over and above the Government reward already proclaimed, making in all 2000 guineas to be paid by His Majesty’s Lords of the Level of Romney Marsh, to any person or persons who shall hand over, or cause to be handed over, the leader of certain evil-disposed persons who ship overseas shorn wool and gold in exchange for rum, brandy, sundry spirits and silks. This desperate character, trading under the name of the Scarecrow, is wanted for trial on a capital charge at the next convenient Assizes, to be held at the Royal Court House at Dymchurch-under-the-Wall in the County of Kent. God save the King.’

Having delivered all this without a slip, he looked up at the window for approval, but Sir Antony, having heard the first bit in which his name was prominently featured, had lost interest and gone to the powder-closet, so the Beadle, somewhat disgruntled after this especial effort, went back to the ‘Ship’. There, he had several more rounds before starting off again. This time, however, he met with greater success, for moving up the village street crying the Proclamation as he went, he became the centre of interest and hospitality. All this only served as encouragement for a visit to the ‘City of London’. This tavern, on the sea-wall, seemed to be filled with his friends, and the four-ale bar was crowded. After a considerable time spent in these congenial surroundings he, like Sir Antony, had very little interest left in the Proclamation, so thinking to settle the matter once and for all, he decided on a rendering then and there. But hoisted by his drinking companions to a position of vantage on the bar counter, he discovered that he had lost the parchment. He made, however, a valiant effort to remember Sir Antony’s phraseology, but like a poorly rehearsed actor, he was lost without his script – and being an inebriated Beadle his voice was lost in the general ribaldry. Early in the proceedings he decided not to try any more ‘Oyezes’, having been unanimously shouted down with a chorus of ‘Oh nos’. So he plunged straight in. ‘That Scrantony Frobtree – on the Level – marsquots – deeming it meet and drink – er – meet and right – oh, well, damning it right and left – out of his person – into the Privy – no-no – oh, well, anyway – sundry spirits and sulks. Desperate character – God save the King.’ And the Beadle, with a loyal gesture, overbalanced and disappeared behind the bar – where kind Mrs. Clouder left him to sleep it off.

Two hours later she woke him, and having cooled his fuddled head beneath the kitchen pump, he recollected to his horror that he had not read the Proclamation to the Vicarage, and knowing that the Squire would most certainly ask Doctor Syn if he had heard it, made up his mind that it was better late than never. The parlour cleared but for a few stragglers, the missing parchment was found on the floor, undamaged save for beer stains and sawdust. So clutching his errant muse he ran along the sea-wall, arriving outside the parson’s house somewhat out of breath. He gave himself a couple of minutes in which to recover it before embarking upon this final test.