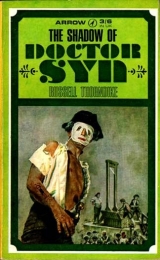

Текст книги "The Shadow of Dr Syn"

Автор книги: Russell Thorndike

Жанр:

Исторические приключения

сообщить о нарушении

Текущая страница: 12 (всего у книги 16 страниц)

Lady Caroline bustled back, and through the open door came the strains of an orchestra tuning up. She begged Cicely to hasten to the ballroom as the guests were already arriving in droves and that she could not see to it all by herself, Maria had vanished and that tiresome gentleman, your dear Papa, was not yet out of the dining-room. From the noise issuing from that room she strongly suspected that he had opened another bin. She would stay and rest awhile with Aunt Agatha, for she knew she was dangerously near a ‘fit of the flutters’.

So for the next hour Cicely, abandoned by the rest of the Cobtrees, played the hostess, launched the party, received and introduced so many people and danced with so many others that she had no time to think of herself.

It was during one of those duty dances that she had the leisure to glance around her, for it was a minuet, and her partner was as slow as the music. For some time she had been conscious of eyes upon her and searched the throng for a sign of him.

When she reached the top of the hall she found him looking down at her from the gallery, which had been thrown open to the villagers and was thronged with eager, shining faces. She was so relieved to see him and to find that he was not dancing with anyone else that her heart missed a beat and, missing a step, she had to do an undignified little hop to right herself. When she looked up again he had vanished. Her heart sank again, yet when the music finished she made her way to the door, and there he was, standing in the midst of a crowd. He saw her – indeed he had been waiting for her – and excusing himself he made his way towards her. ‘Why, Cicely, child,’ he said in his best parochial manner, ‘you must not overtire yourself. You have been dancing for the best part of an hour. I know you will find it hard to tear yourself away from all these young men, but I prescribe a rest and a glass of punch.’ He put his hand under her arm and led her swiftly through the hall. Not a word was spoken, but she seemed to understand, for she ran from him to return with a hooded cloak, and together they went out. In the muddy drive he stopped, picked her up and carried her in his arms through the lych-gate to the Church Tower.

Kicking open the door he stepped into the dark and then on and up the spiral steps he carried her – through the bell-chamber, and at last the battlemented roof. Here he set her down, and holding her at arm’s length they neither of them spoke, but were content to gaze. And thus they stood until their spirits merged and became one with wind and stars and hung there motionless in space.

* * * * *

From some mid-distance came the hooting of an owl and in a dry dyke half a mile away a pair of merry eyes looked up in the direction of the Tower, waiting for a signal.

It came – a vivid flash – and then again, answered from far away by moving lights that joined and came towards the watcher, while the hooting of the owls grew louder, moving with the lights towards Dymchurch Tower.

* * * * *

Miss Gordon was enjoying herself. She was seated in a cosy alcove within ear’s range of the music and within eye’s range of all that was going on, surrounded by the Lords of the Level and young officers of Dragoons. They were all paying her the attention that they might have shown to a young and beautiful woman. In fact, Agatha Gordon was holding a court. Her slender foot tapped, her lace fan fluttered, and her bright eyes danced this way and that. While she was allowing herself a few moments’ relaxation by listening with but half an ear to a rather stodgy old gentleman, out of the corner of these same bright eyes she distinctly saw beneath a tapestry a golden brocaded dress and a pair of elegant buckled shoes with black silk hose attached go swiftly through the Hall. She had hardly stopped smiling to herself in satisfaction when the Squire came up and asked if she had seen that minx Cicely. To which Miss Gordon replied that indeed she had not seen the best part of her niece for the best part of an hour, but that she herself would like to dance and would he lead her out. She was laughing to herself at her neatly turned yet truthful phrase when she passed Maria, who was attempting to interest Major Faunce, and she commanded them to come and join the dance since it was nigh twelve o’clock and she was going to cut her birthday cake. She did not fail to notice Maria’s black look but sailed on to the ballroom on the arm of Sir Antony. By the time she had led the unwilling Squire through the complications of quadrilles ’twas but a few seconds before the hour, and all the guests assembled at one end of the room to watch the ceremony. But no sooner did the first stroke of midnight ring out than the orchestra sounded as though they had become confused, one half played one tune and and the other struck up a different though more familiar air. This finally won the day and soon the whole room had it. On the first notes some quickly hushed titters were distinctly heard coming from the gallery. Agatha Gordon laughed outright, for the tune was none other than the ‘British Grenadiers’. But the turne persisted and the titters grew louder, for the villagers knew what it meant and hoped to see some fun. Then suddenly the ballroom was full of masked figures who moved swiftly in and out, driving the company before them with cocked pistols. The guests were too astonished to protest, though there were a few screams and some convenient faintings into the arms of the nearest gentlemen. Some thought it was a joke, for it was all so swift and orderly, and the surprise was complete. But hardly had they regained their breath when from the great window behind the orchestra there leapt a fearsome figure, masked and cloaked, who cried out: ‘The Scarecrow at your service. And for once you need not be afraid. I have come to pay my respects to the lady whom you are honouring tonight, Miss Agatha Gordon.’

If anyone else was afraid, certainly Miss Gordon was not. She revelled in it, as with great strides he reached her and swept a low bow. ‘Will you do me the honour of treading a measure, ma’am?’ he said. The crowd were aghast. ‘Such impudence! What audacity! What will Miss Gordon do?’

But this lady merely dimpled and held out her hand, for she had seen that prominently displayed upon his black cloak was a golden riding-whip with a diamond handle. He called for a minuet and the company, watching spellbound from a distance, saw her talking and laughing. To a graceful rhythm the dancers moved – the tall gaunt Scarecrow and the little silver lady.

Point down one. Point down two. Sweep, bow. Curtsey.

‘I got your invitation, ma’am,’ he whispered. ‘And I wouldn’t have taken the risk for anyone else.’

Again point down one. Point down two.

‘You’re a naughty, wicked rogue,’ she said. ‘But I hoped you’d come.’

Sweep. Bow. Curtsey.

‘I see you are wearing my brooch, ma’am. So I hope I am forgiven.’

‘I see you wear mine, sir. You certainly are.’

The Scarecrow had moved nearer to the pillaried entrance, where, spying a figure dressed in black, he called out, ‘Why, Doctor Syn, my greetings to an enemy. Come, sir, I’ll be generous. Let me see if you can dance as well as you can preach. ’Tis my command. We’ll dance a foursome. Bring out the golden lady standing by you.’

Here was entertainment indeed. The villagers hung open-mouthed over the gallery, jostling for place. What would the parson do?

The parson stepped out on to the floor, and sweeping a most accomplished bow to Miss Cicely Cobtree gave her his hand and led her out. The band struck up a merry jig, and the strangest dance that was ever seen began. All four were voted good, but the village had it that the Vicar was by far the best, while the four dancers never enjoyed themselves so much, each knowing who the other was and thoroughly appreciating the joke.

The music stopped ’midst thunders of applause, but when it seemed that the Scarecrow was about to take his leave, Miss Gordon had a sudden inspiration. In ringing tones so none could fail to hear she cried: ‘Since I have granted you your wish and trod a measure, I have a request to make from you. There is a problem to be settled. Indeed it will benefit you, sir, if I am right. Some say the Scarecrow is none else but Captain Clegg the Pirate, and bears upon his arm a strange tattoo – the mark of Clegg. Come, sir, roll up your sleeve and end this argument for good and all.’

Again the spectators held their breath, while the Scarecrow swiftly rolled his sleeve and showed his forearm – bare. Such a burst of cheering had never yet been heard in Dymchurch, while the Scarecrow, bowing over Miss Gordon’s hand, whispered: ‘You’re the bravest, cleverest Scots lassie I have had the privilege of robbing and dancing with.’ And he was gone, and with him went the Nightriders.

The cheers lasted for ten minutes, for though the Dymchurch villagers were used to exploits of the Scarecrow this was perhaps the pleasantest, most entertaining and romantic they had ever known, while even Mrs. Honeyballs was forced to admit that the Scarecrow behaved himself so nice that she wouldn’t have minded dancing with him herself. But a goodly proportion of the cheering was directed towards the little old lady herself, for they all agree that she had behaved print1 and peart,2 and it was a good thing that she had so neatly cleared up that silly theory once and for all. Now everyone knew that their Scarecrow was not that pirate Clegg. The gentry for their part were just as enthusiastic, and the whole gathering was so busy with this gossip that it was not for fully twenty minutes that Miss Agatha remembered her cake. She could not think when she had enjoyed herself so much and she chuckled at the audacity of Mr. Bone, while fully appreciating who had been at the back of all this scheming to make her birthday party pleasant, so she was very glad that she had had the sense to explode for him the theory about Clegg. Now Clegg could rest in peace unless someone was very careless. So she gave herself a mental pat on the baack and felt that for eighty she had really not done badly. Her pleasant reverie was interrupted by the Squire, who, having hung about on the fringe of the proceeding all the evening, feeling rather out of it in his own house, was not in the best of tempers.

So he asked her somewhat testily when she was going to cut that confounded white mountain of confectionary that was clutterin’ up his library, though he failed to remark that he thought that same piece of white confectionary would look just as well sittin’ on her head as what she’d already got on it. It only lacked a feather – and he wished he had the courage to stick one in.

1 Bright. 2 Lively.

Aunt Agatha agreed that what with one thing and another she’d forgotten about the cake. But as the custom was to use a special dirk for cutting it, someone must go and fetch it, since she never travelled without a good sharp pair of them. She called for Lisette, who knew where they were. Lisette, however, was at the moment getting more fully acquainted with the English and their outlandish customs. Therefore she was blissfully unaware of her mistress’s need of her. Aunt Agatha’s impatience almost resembled the Squire’s for she thoroughly dratted all foreigners and said she would fetch them herself, and that meanwhile her candles were to be lighted.

Tripping back along the east wing with Mister Pitt in attendance, she was humming lightly the ‘British Grenadiers’. Rounding the corner into the Long Gallery she saw something extremely suspicious. In fact, she could hardly believe her eyes, for having seen the Scarecrow disappear through the window about twenty minutes before, what was he doing peering about in such a nasty way outside the best bedrooms? For one ghastly moment she thought she had been wrong about Mr. Bone, but then the figure straightened itself, and standing with its back towards her she knew by the shape of the shoulders that this was not her naughty rogue. Aunt Agatha’s instinct for the cut of a man’s jib was infallible, and her good Scots blood was up. Who was this upstart who dared impersonate not only one, but two of the people of whom she was extremely fond? She advanced swiftly and silently, while Mister Pitt, who for all his ribbons, bracelets, and trimmings also had within him the blood of fighters, emulated his mistress and crept forward with quivering nose. Dirk in hand Aunt Agatha struck, and in the words of the Psalmist – ‘in the hinder parts’, putting the prowler if not to perpetual shame certainly to momentary discomfort, for the point was sharp and Aunt Agatha had a strong wrist. He let out a howl of surprise and pain which coincided with Aunt Agatha’s Gaelic war-cry and command to proceed, while Mister Pitt carried out a series of worrying sorties under his own generalship. Down below in the library the candles (eighty) had been lit and the cake was ready to be borne round the ballroom by two powdered flunkies, while the orchestra had already started (what they thought) a brilliant imitation of the bagpipes. So to the skirlings and whirlings of this music and uttering many strange cries of her own, down the stairs and into the ballroom came in triumph Miss Agatha Gordon of Beldorney and Kildrummy, preceded by her prisoner and the never flagging Mister Pitt.

Realizing that something had gone wrong and that this figure was obviously some impostor the guests pressed round to see the fun. But the villagers grew suspicious and angry and very soon the whole place rang with boos and cat-calls. The more adventurous came down from the gallery – then all followed suit. Crowding the ballroom the pressed round the pretender, and things might have gone badly for this unfortunate, had not Doctor Syn saved the situation. He spoke to his parishioners – reminding them that they were guests in Sir Antony’s house – he made them smile – he made them laugh – and soon order was restored. He and Major Faunce relieved Miss Gordon of her charge and took him to the Chief Magistrate, Sir Antony. The man, more angry than frightened, for he was within his rights, was ordered to remove his mask. He proved to be none other than the new Revenue Officer from Sandgate, Mr. Nicholas Hyde, at whose discomfiture both the Squire and Major Faunce were secretly delighted. When the Squire angrily demanded what he had been doing in the Court House in such a garb, Mr. Hyde retorted in similar tones that seeing that his job was to catch the Scarecrow he was at liberty to use any methods to do so, and as he suspected everyone and made no bones about it, Sir Antony included, he thought that by dressing as the Scarecrow he would find out who was and who was not friendly towards the rogue. That was his explanation and he stuck to it. But as Mr. Mipps so aptly remarked afterwards: ‘Serve him right for prowlin’. And if he tries to sit down, he’ll soon find out who his friends are in these parts, and it don’t always do to set a sprat to catch a mackerel.’

Chapter 19

November Lightning on Toledo Steel

Mr. Mipps’s chin dropped as his head fell forward. His pigtail shot up and he awoke with an agonized cry, and a disgruntled ‘Aye, aye, sir’. His hand went to the back of his neck and rubbed away the pain. He yawned and then with some difficulty opened his eyes, while fishing with the lanyard wound round his neck for the enormous timepiece attached to the end of it. This silver turnip seemed to possess an independence of its own, for its master never knew into which pocket or beneath what garment it had come to anchor. He was not surprised, therefore, when after several tugs on the lanyard, it dislodged itself from beneath his ribs, and made a chilly passage up his chest. He studied it carefully, and yawned again. Five minutes to go before rousing the Captain, for Mr. Mipps was doing the middle watch. Sitting cross-legged on a high-backed chair in the library, he had endeavoured to keep awake. But being tired through lack of sleep the night before, and not being a man to leave a thing to chance, he had evolved a plan for keeping himself on the alert. By an intricate contraption of nautical loops and knots, he had lashed his tarred queue to the back of the chair so that if he dozed off and sagged forward, he got a rude awakening with a sharp pain in his jigger-gaff. This had just worked according to plan, and as he had no further need of its spiteful cooperation, he leant back, hooked his finger through a loop, pulled, and was free. He then uncrossed his legs with difficulty, got up and kicked the logs into a blaze. Shaking himself and taking a swig at the brandy-bottle completed his operation of waking up. This done, he mentally weighed anchore, and cramming on canvas, set to work lighting the candles and generally getting things ship-shape. Usually when doing these things, he would accompany his movements humming his own particular ditty – the Song of the Undertakers, composed by himself, which accounted for the gloom of the subject and the liveliness of the tune. On this occasion, however, he was not in the mood – which meant that he was worried.

Mr. Mipps was an optimist. He had a cheerful disposition. In fact, there were but two things that had the power to upset him – the insolence of Officialdom, for whose bungling he had a supreme contempt, and the fortunes of his beloved master. After so many years of faithful service, sharing storm and calm alike, he knew Christopher Syn so well that he could tell in a second the state of his mind by every expression, every gesture, and each inflection in his voice. He had already realized that his idol had two sides to his character

– the dreamer and the man of action, and while he respected the first he preferred the latter because he understood it. Lately, however, Mipps had been baffled by a cerain sort of vagueness in his manner, and yet on thinking it over he realized that this casual preoccupation was accompanied or closely followed by reckless high spirits.

It might have been that this new restlessness had made the Vicar feverish, but this was no case for Doctor Pepper, for no one knew better than Mipps that there was nothing wrong with his physical health, and this gave rise to the nasty suspicion that he was mentally sick – in fact, that he was in love. He was genuinely worried, for on the only two occasions when there had been anything wrong, his master had been spiritually hurt – the cause in both cases being a woman. The first – his young wife’s infidelity, which turned him pirate and sent him raging round the world to seek revenge, and the second – the death of Miss Charlotte, which had sent him temporarily insane. Not that Mr. Mipps disliked women or did not want Doctor Syn to find happiness with one, but he had a feeling at the back of his mind that it would be wrong, because as far as Doctor Syn was concerned, women had spelt ‘Disaster’, and it was for this reason alone that Mr. Mipps had always remembered Clegg’s slogan: ‘No petticoats aboard’. But here was Clegg himself forgetting to remember his own orders.

This seemed almost fatal to Mipps, because in his twisted little soul he felt that it would be only through a petticoat that Syn could come to grief, and his curious sailor’s instinct corroborated this idea. Yet with these disquieting thoughts filling his mind he, too, had forgotten something, which was that, within the next hour, his master had other dangers to face.

A low rumble as from distant guns reminded him of this, and alert once more he hurried to the window, anxious about the weather. It was pitch dark, sea and land black – the sky a menacing copper. Another low dull grumble from the heavens. The whole night was filled with foreboding as if it were attuned to the Sexton’s thoughts. But with an effort he changed them and coming out of the deep waters, he went briskly to the fireplace, picked up the kettle for the shaving-water, and went up the stairs to wake the Vicar. And as he climbed aloft, he sang defiantly the Undertaker’s Song.

On leaving the Red Lion Inn at Hythe about this time, Captain Foulkes was in high spirits. He had had an excellent supper, and then whiled away the few hours preparatory to starting out with a pair of bright eyes and several bottles of wine. Doctor Syn’s letter was in his pocket, telling him that he had managed to arrange his desired meeting with the Scarecrow and asking him to present himself at the Vicarage at 4:30 on the morning of the 20th, as the place of assignation was but a few hundred yards from his house. He was full of confidence that the Scarecrow would see eye to eye with Barsard and he intended to get a written agreement authorizing them to use the smugglers’ fleet. He laughed out loud when he thought upon his next step, which was to carry out his original plan and to win the wager. When all was said and done – one could always find a use for two thousand guineas – if only to buy back the smiles of that sulky Harriet. He was still safe as regards the time limit, by leaving the coast at daybreak and riding post-horses he could be in London that night, with a day to his credit. As to the proof of his winning the wager, it was all too easy. Since, as the old parson seemed to enjoy London and to frequent the gaming houses, he would be only too glad to come up the next day by coach to be his guest for a day or so. Indeed, since Doctor Syn had expressed his wish to act as second, and had confessed his passion for watching sword-play, why then let him do so. He’d see the best fight he’d ever seen and was unwittingly playing into the Captain’s hands. He laughed again when he thought of the stir he would cause in London by taking the parson with him into Crockford’s and making him tell Sir Harry Lambton and the rest what he had seen. He did not deceive himself that they would believe his story without this proof, but damme, they would have to take Doctor Syn’s word by reason of his cloth, and was he not a friend of the Prince Regent?

While the lights of the ‘Red Lion’ were still glowing behind him these intoxicating thoughts seemed only to need this five-mile ride before materializing. But as he rode on, and the way curved in and out the dykes, not only had the shining windows disappeared but with every yard the way grew darker. He was glad that the ostler had advised him to carry the stable lantern, which he now held in his right hand, swinging it this way and that, peering into the darkness to enable him to distinguish road from dyke. This demanded all his concentration, for not only did his way become increasingly difficult but his visions of success became equally obscured, and in their place unwelcome thoughts took shape. Then his horse shied, and the Captain, cursing, thought he saw a scoffing luminous face that grinned at him from the further side of a broad dyke. He looked again, but it had gone, and other shadows took its place. Then he became aware that there was movement on the Marsh around him. He spurred the frightened animal on, but whether he went fast or slow he heard the sound of horses’ hoofs behind him. And then he lost his way, and followed a light that seemed to dance ahead of him. It led him past the dark lump of some small hovel from whose chimney there oozed red, oily smoke, then on, and over a bridge that sagged into the water as he crossed, while behind him from the evil spot he had just left came unearthly screams and mocking laughter. Somehow he found the road again and at last came into that long stretch that runs beneath the sea-wall. It was then he heard a distant angry rumble of thunder and as he looked at the ominous sky a great white undulating mass leaped up before him and with a cold embrace it crashed about him and disappeared. He was wet through, but spurring hard the next wave fell behind him. It did not take him long now to reach the Vicarage, for he remembered exactly where it was. He tethered his horse at the gate and rang the bell, and as he waited for admittance, he realized that he was late, cold, and extremely uncomfortable in mind and body.

Doctor Syn was waiting for him and deplored the state of his clothes. He begged him to come and dry himself by the library fire, while Mipps saw to the horse. After a warming glass of grog in this pleasant atmosphere, the Captain recovered something of his spirits. He asked Doctor Syn what arrangements had been made, whether the rendezvous would be a private one, or if the Scarecrow would have his followers with him. He explained that though it took a lot to frighten himi, he had had a most uncanny ride, and that he would welcome Doctor Syn’s presence at the meeting, because being a holy man it would counteract the evil of this devil-ridden place.

He used this flattering argument to get the Vicar on his side, because he realized that should he be seen killing the Scarecrow after he had struck a bargain, he must show some very strong motive, and determined to use the excuse that he was ridding the community not only of the Scarecrow but Clegg as well. So he brought the conversation round to this by asking Doctor Syn if he had met a certain Major Faunce – though he did not expect the reply that he received.

‘Major Faunce – oh dear me, yes!’ said the Vicar. ‘I was but dining in his company last night – a charming man – I knew his brother very well. They both strongly adhere to your interesting theory that the Scarecrow is in truth the pirate Clegg. I listened to him most carefully – and I knew that he was right.’ Doctor Syn seemed quite pleased that he had discovered this incriminating fact about his sworn enemy – but what he said next staggered the Captain, for it almost appeared that he had read his thoughts.

‘Well, sir,’ he remarked blandly, ‘since as you doubtless know there is one way of proving this common identity, the tattoo upon Clegg’s arm – why do you not take this occasion to provoke him – dare him to show it to you and then…’ – he made a vague gesture. ‘Oh, I know you told me you only desired a meeting,’ he continued, ‘but really, sir, think what a benefactor you would be in ridding the community of such a tyrant – I must confess I am heartily sick of having to use his identity to keep my parishioners in their proper places. My sermons – you know.’

Captain Foulkes was amazed. ‘S’death,’ he thought, ‘the parson’s positively bloodthirsty.’ He warmed towards this curious creature and began to appreciate why that damned rogue Prinny cultivated him, for an unscrupulous cleric can be plaguey useful in more ways than one. His chief worry had vanished, for he was now sure of co-operation and he became again the confidant swaggerer.

‘Come, then,’ he cried, ‘one more drink, a toast to a death that shall be nameless – and let me couple it with long life to Doctor Syn.’

With a charming smile the Vicar raised his glass. ‘I find you so persuasive, sir – I repeat: “To a death that shall be nameless and” – he chuckled – “long life to Doctor Syn.”’ They put down their empty glasses.

The Captain regarded Syn appraisingly. ‘I had a mind,’ he said casually, ‘to go unarmed – but since you too are so persuasive, I think it would be best for our own safety to carry swords. I take it that if the occasion should arise, you are still willing to be my second?’

The Vicar seemed to be childishly delighted and accepted this great honour. ‘I will most certainly go as your second,’ he replied. ‘But you have so imbued me with the fire to destroy a villain that I could wish the pleasure were mine.’ Here Bully Foulkes so far forgot the respect due to this wolf in sheep’s clothing that he clapped him on the back saying that he was glad to meet such a sly dog.

Curiously enough the parson, also laughing gaily, replied in French: ‘L’eau qui dort est pire que celle qui court. A good proverb, sir, and one I flatter myself I have always lived up to. For indeed a calm exterior is more to be feared than a Bombastes Furioso —’ Then seeing that the Captain’s laughter had somewhat abated, he said: ‘We must not let our sense of humour blunt our purpose, for our swords are as sharp as our sense of duty.’

The Vicar’s servant also appeared to have a sense of duty, for upon that instant there was a respectful tap upon the door, and bidden to come in he stood humbly pulling forelock, though only his master saw the excited quivering of his jigger-gaff.

‘Beg pardon, sir, for interruptin’, but you asked me to remind you at odd moments about Mrs. Wooley’s complaint.’

‘Oh, dear me, yes,’ replied the Vicar. ‘I had indeed forgotten. I shall start almost at once. Thank you, my good man.’ He turned to the Captain and said with what might have been a wink: ‘A poor old woman is in need of comfort. You understand.’

The Captain understood. ‘Zounds,’ he thought, ‘the fellow’s a marvel. He has the wit to keep it up in front of his servant.’

‘Well, sir,’ went on the servant, ‘if you’re a-goin’ out in all this dark, I’d best come with you with a lantern.’

The parson shook his head. They would take the pitch-torches, he said, and bade his servant go to rest. But the servant persisted, ‘I never rest when you’re out. Are you sure you’ll be all right? There’s a storm comin’ up. I knows it by them curlews.’

The Vicar did not appear to have heard this last remark, for with a silken handkerchief he bent down and flicked one buckled shoe. ‘Dear me,’ he said. ‘Too bad. Mud.’

The Captain was amused to see that the servant’s face was a study in injured innocence, and that as they left him he was shaking his head and reproving himself with ‘Tch, tch, Mud. What a pity. Mud.’

As they crossed the bridge on to the sea-wall, a vivid flash of lightning lit up the sea which, as the thunder rolled away, made the darkness denser. Each with a flaming pitch-torch held high, they made their way, casting fantastic shadows on the narrow, grassy track, one side a sheer stone drop, curving away below into the sea, which now lashed angrily against it. The track widened about a look-out hut and here the parson stopped. ‘This is the spot,’ he whispered, and stuck the handle of his torch into the wind-drift sand. ‘Do you wait here in this shelter, for I am pledged to go alone and tell the Scarecrow that all is well and this is not a trap.’