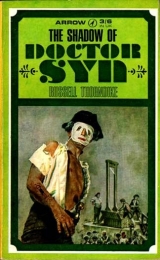

Текст книги "The Shadow of Dr Syn"

Автор книги: Russell Thorndike

Жанр:

Исторические приключения

сообщить о нарушении

Текущая страница: 6 (всего у книги 16 страниц)

Mr. Mipps was filling a second churchwarden for the Vicar when the Beadle’s bell sounded and the speech began. Doctor Syn went to the bow window, and pulling the curtains wide looked out over the moonlit Marsh. He stood listening to the Proclamation – Mipps followed him and handed him the full pipe.

‘Hear that, Mr. Mipps? Two thousand guineas.’

‘Our price goin’ up, eh?’ Mr. Mipps whispered.

‘Two thousand guineas would be of great benefit to our Sick and Needy Fund. I suppose you have no idea as to the whereabouts of this deplorable ruffian?’

‘Me!’ echoed the Sexton. ‘Why me? ’Aven’t you got an idea?’

At that moment there was a sharp knocking on the front door – which caused the Vicar to answer: ‘No – but I have an idea that this may give us an idea. The door, Mr. Mipps.’

Giving the Vicar a quizzical look the Sexton went to open it.

Chapter 9

The Revenue Man Pays a Social Call

A curious feature of all the front doors in Dymchurch was that they possessed spy-hole grids. This enabled the person inside to identify a visitor before allowing admittance. It was wise to take this precaution if one’s activities happened to be questionable. Who knows? It might be a Bow Street Runner or the Revenue. Mr. Mipps always took this precaution, and having done so, closed the grid, uttering in a coarse whisper, ‘You know who it is, don’t you?’

The Vicar nodded, and repeated, ‘Open the door, Mr. Mipps,’ which the Sexton did somewhat reluctantly. A tall man stepped into the room and quickly looked about him. Seeing Doctor Syn, who was standing by the fire, a look of courtly query on his face, the stranger bowed and advanced towards him, saying: ‘Doctor Syn? Your pardon, sir. Revenue Officer from Sandgate. Nicholas Hyde, at your service. I should like a few words with you, Reverend Sir – alone.’ The last word directed at Mr. Mipps, who stood resentful and alert in the background. The Vicar bowed and said he was happy to make Mr. Hyde’s acquaintance, and then requested Mr. Mipps to leave them alone, which the Sexton did, throwing back a look of disgust at the Revenue man. Doctor Syn invited his visitor to take a seat and asked him if he would care for a drink, and upon the other’s, ‘Thank you, sir,’ poured him out a generous measure of brandy.

Mr. Hyde sat down in the chair to which his host had motioned him and took the proffered glass, while Doctor Syn watched him as he lit his long churchwarden from a taper at the fire.

He saw a broad-shouldered, determined-looking man, who, dressed in the dark drab uniform of the Revenue, had about him an air of pugnacious expectancy and the questioning look of suspicion which was the stamp of his trade.

The Revenue man, feeling it was his duty to watch people and not to be watched, shifted uneasily under the Vicar’s penetrating glance. This was not at all what he had expected. His customary habit of generalizing both people and facts had failed. Here was no ordinary village parson in a humble Vicarage, but an elegant figure of fashion in a setting artistic and luxurious. So, realizing that he could not use his bludgeoning manner here, decided on different tactics, and awkwardly opened the conversation with a compliment.

‘This is an excellent brandy, Doctor Syn.’

‘I am glad you find it to your taste, sir,’ replied the Vicar, as he strolled completely at his ease to a chair at the refectory table. ‘The Squire sent over some half a dozen bottles, as he was dining with me tonight.’ Thereupon, seeing the other’s quick glance at the bottle, he continued: ‘Oh, you need have no professional qualms as to his credentials. He is our Chief Magistrate – Caesar’s wife, you know.’ Mr. Hyde, not being conversant with classical quotations, looked blank. So the Vicar added: ‘Yes, well, perhaps I am mixing my metaphors; Sir Antony hardly resembles a frivolous Roman matron, eh?’ Another blank look from the Revenue. ‘But perhaps you have not met the Squire? Your visit to Dymchurch is not connected with law-breaking? Gratifying indeed, Mr. Hyde? A personal matter? You come to ask me to publish the banns? You could not do better. Our Marsh girls are considered beauties, you know.’

Here at least was a statement that Mr. Hyde could understand and answer. ‘I am sorry to disappoint you, Parson, but I am not a lady’s man. Let me be frank with you, sir, my visit to Dymchurch is strictly in keeping with my profession.’ Placing his elbows on the table, and leaning towards Doctor Syn, he added impressively: ‘I am here to lay that rascally Scarecrow by the heels.’

The Vicar, raising an eyebrow in surprise, asked him why he had not gone to the Squire, to which the Revenue man, begging his pardon, explained that he had been informed that Sir Antony Cobtree cared more for his foxhounds and his vintage port than he did for maintaining the Law, a Leveller of Marsh Scotts. The Vicar was about to expostulate, but Mr. Hyde cut him short with: ‘And anyone wishing to do business with him after a certain hour is more like to find him under the table than in his chair of office.’

At this the Vicar protested: ‘You do him an injustice, sir. The Squire of Dymchurch is moderate in all things; indeed, he is looked upon with great respect by his tenants.’

Mr. Hyde capped this derisively: ‘That’s as may be, sir, seeing the Squire’s known to wink the other eye.’

Doctor Syn rose, and in a reproving tone told the Revenue man that he would not allow a guest to remain under his roof who questioned the integrity of his benefactor. His attitude conveyed dismissal. Mr. Hyde, cursing himself for a clumsy fool and having no mind to go before accomplishing his mission, apologized as far as his nature allowed, and explained that he had no wish to offend but that suspicion being his trade, he must, of necessity, suspect anyone who could tally with the Scarecrow’s description, adding with conciliatory jocularity: ‘Why, I might even suspect you were you as good a rider as Sir Antony and not known to be one of the Scarecrow’s sworn enemies. Your sermons against this cunning rogue are highly spoken of, as is, indeed, your courage in delivering them; that is why I seek your assistance.’

At which the Vicar, having reseated himself as a sign that he had accepted the other’s apology, seemed amused, and enquired whether Mr. Hyde was suggesting that he should ride out with the Dragoons on their man-hunt.

Mr. Hyde snorted. ‘Man-hunt?’ he cried. ‘Devil-hunt, more like, for I begin to think the creature’s supernatural.’ Then his tone became confidential. ‘No, Parson, I am not asking you to do anything but give me such help as your calling allows. In a word, I want you to impart to me any information you may have heard, or any suspicions you may have, regarding the questionable activities of your parishioners.’

At this the Vicar seemed deeply shocked, as he replied in severe reproof: ‘Let us understand each other once and for all, Mr. Hyde. If I can be of any help to you be preaching more strongly against this evil, I most readily agree, but I should be a disgrace to the cloth were I to betray the sorry little secrets of my flock,’ adding devoutly that he considered it his bounden duty to respect the confidence of all – black sheep or white. He smiled as he explained himself more fully: ‘Revenue man and smuggler alike. A little more brandy, Mr. Hyde?’ The Revenue man was completely baffled; he felt he had not made the progress he had anticipated, so to gain time he accepted the brandy before replying: ‘You’re spoken of as a good man, Doctor Syn, but I venture to think that you have not been so closely connected with crime all your life as I have.’

With this the Vicar agreed. ‘Possibly not, Mr. Hyde. Possibly not. Possibly you could teach me a very great deal about crime.’ Then seeming suddenly to change his mind, he suggested that perhaps they should work together after all, adding with timid eagerness: ‘Do you really think we could catch this, er – rascally Scarecrow?’

This was the attitude that Mr. Hyde understood, and he replied bluffly: ‘All in good time, Parson, all in good time. Glad to see you’ve changed your mind, though if all goes well tonight, I may not need your help, for Major Faunce and his Dragoons are already combing the Marshes beyond Dungeness.’ Doctor Syn seemed most interested, and the Revenue man, flattering himself that he had subdued the parson, and was on the way to getting what he wanted, continued aggressively: ‘That infernal Scarecrow had the audacity to send me a note with details of tonight’s man-hunt – but I’ll fox the rascal. I have a special troop well hidden in Wraight’s Building Yard.’

The Vicar stared at him with astonished simplicity, and in a voice filled with admiration, said: ‘Dear me, Mr. Hyde, dear me. I fail to see how this rogue can ever hope to pit his wits against yours – remarkable foresight on your part. The Building Yard? Now whoever would have thought of the Building Yard? Indeed, you have quite convinced me, I cannot go wrong if I listen to you.’

Mr. Hyde was delighted and so full of self-satisfaction that he could hardly speak, and so Doctor Syn continued: ‘But should you not succeed tonight, do not fail to tell me how you next intend to trap him, and let us see if my poor brain can add anything to that.’

The Revenue man, seeing his object in sight, felt he could afford to be a little condescending, so he thanked the parson, adding: ‘They say two heads are better than one.’

Instantly the Vicar replied: ‘Dear me, do they? I find mine quite satisfactory. I should not like to lose it. It is as valuable to me as I should imagine the Scarecrow’s is to him.’

Mr. Hyde chuckled in confident anticipation. ‘His won’t be worth much by the time we’ve finished with him, eh, Master Parson?’ His object achieved, and by now thoroughly convinced that his first impressions of this old clergyman were wrong, and that he was, after all, just as simple as the rest of his class, he rose and said that he had better be about his business, for although he would not get much rest this night, there was no reason why he should keep Doctor Syn from his.

Doctor Syn, on his part, remarking that he was loth to see such an entertaining visitor depart, escorted him personally to the door, where the Revenue man bowed, saying: ‘Thank you for your hospitality, Reverend Sir, and good night.’

Doctor Syn returned his bow with a cheery ‘Good night, Mr. Hyde, and thank you. Your confidence is flattering – and most enlightening.’ But had Mr. Hyde known just how enlightening his confidence had been he would not, upon leaving the Vicarage, have been quite so pleased with himself.

Chapter 10

With the Scarecrow’s Compliments

Doctor Syn closed the front door and chuckled at the assurance of the Revenue man, and after reflecting how completely his play-acting had succeeded, the chuckle grew into a laugh, and when he thought that had Mr. Sheridan seen his performance he would certainly have recommended him as a comedian, his laughter grew the louder. Indeed, he was laughing so hilariously that he did not notice that Mipps had returned and was standing beside him.

The Sexton’s tone was plaintive. ‘You might, at least, tell me the joke. I don’t see nothin’ to laugh at. Least, not at a Revenue man. Funny – never liked ’em. Never saw nothin’ funny in ’em, neither. And if he ain’t goin’ to get no rest, he ain’t goin’ to keep awake doin’ nothin’ funny under our windows.’ And with this philosophical resolve Mr. Mipps went briskly to the curtains and pulled them close with an extra tug or two to show his indignation. By this time Doctor Syn’s laughter had dwindled back into chuckles.

‘Oh well, p’raps it was Wraight’s Building Yard you was laughin’ at,’ pleaded Mipps, trying to get some sort of response from his master. This had the desired effect, for the Vicar raised a questioning eyebrow. Mr. Mipps knew what it asked and proceeded to explain. ‘Oh, begging you pardon but anticipatin’ nothin’ humorous knowin’ what Revenue men are, me ear didn’t seem to want to get away from the key’ole. “Mr. Mipps,” it said to me, quite jealous-like, “you’re always thinkin’ of your weather eye, now pay a little attention to your weather ear.” I couldn’t get it off, sir. Got paid itself out. It was burnin’ fiery ’ot at the things he said about the Squire, and it positively blushed when you got on to them piebald sheep.’

‘Then your sensitive ear has saved me the trouble of repeating it,’ said the Vicar quietly, and then dropping his voice still lower, spoke quickly and urgently: ‘You know the plans for tonight, but warn the men to keep clear of Wraight’s Yard. Put sentries round to report any movement of the Dragoons. Tell Vulture and Eagle to be in the Dry Dyke under the sea-wall in a quarter of an hour. And now we know which way the cat is likely to jump, tell Jimmie Bone when he returns as the Scarecrow from the false run to ride out again and see that the remaining Dragoons upon the Marsh are well and truly lost. I shall not need him as the Scarecrow tonight for the “run proper”. I must do that myself. There will be too many decisions to be taken on the spur. That’s all, I think. The horses were all listed. Ah, yes. That reminds me. The Squire’s stable. The horse called Stardust. See no one touches it.’

It was now Mipps’s turn to look quizzical. ‘Oh! In case someone wants to ride it tomorrow?’

‘Yes, Mr. Mipps,’ replied the Vicar. ‘In case someone wants to ride it tomorrow.’

‘I see.’ The only thing Mr. Mipps really did see at the moment was that he was thirsty, and knowing that their thirsts were usually simultaneous, he asked the Vicar hopefully if there was anything he wanted, adding as an extra hint that laughing was thirsty work. But this time, however, their thirsts did not coincide – for Mipps had certainly no taste for what the Vicar wanted.

‘Water?’ Mr. Mipps could hardly believe his ears.

‘Yes, Mr. Mipps. Water. I asked you to fetch me a ewer of water.’

‘Oh, water.’ His tone conveyed that he had never heard of it, and although he went upstairs to find some, he continued to mutter question and answers during his search. ‘“Water?” I says. “Yes, Mr. Mipps. Water”, he says. “Water?” says I. “I asked you to fetch me a ewer of water.”’ Mr. Mipps shuddered. ‘Ernful stuff.’ He was extremely glad that he had had the foresight to refill his flask with brandy. He felt in his pocket for comfort, then remembered that he had left it in the kitchen, so with a fervent hope that Mrs. Honeyballs hadn’t been at it, he decided that the only thing to do in this emergency was to go and find out if she had. By this time he had forgotten what he was looking for, so having wandered aimlessly into the Vicar’s bedroom – wondering why he was upstairs and not downstairs, he looked wildly about him for assistance. ‘Come up for something,’ he muttered. ‘Come up for wot? I dunno – brandy?’ No. No. Downstairs – hope she hasn’t been at it…. Now what am I ’ere for?’ He had asked himself this question several times before his weather eye decided to befriend him. It came to rest upon the Vicar’s washstand, where, reposing innocently in its basin, was the object of his mutual stress. Water. So before it could elude him again he seized it and hurried downstairs, with a twofold prayer that it would not finish the Vicar, and that Mrs. Honeyballs hadn’t finished his brandy.

The first part of his prayer was answered when, upon handing over the bedroom ewer, Doctor Syn did not drink it. Instead, after a polite, ‘Thank you, Mr. Mipps, I began to fear that perhaps my well had run dry,’ he did a stranger thing. Lifting a corner of the heavy cloth that covered the refectory table, he threw the ernful contents under it. Upon the instant, Mipps understood. With a long-drawn sigh of relief he said to the Vicar: ‘You did give me a fright, sir. I thought you wanted water. Silly of me. I see. Better go. Your well ain’t dry, but mine is. Least, I ’ope it ain’t.’ And hurrying off, he discovered that Bacchus was on his side and that the second part of his prayer had been fulfilled. Mrs. Honeyballs’s weather eye had let her down.

From beneath the refectory table came the protests of a disturbed sleeper. Oaths, yawns and splutterings, and in a short while there appeared the rubicund face of the Squire, his bald head bereft of wig and folds of the tablecloth draped about him like a toga. Doctor Syn regarded him with affectionate amusement. ‘Not Caesar’s wife, Tony. Egad, you’re more like Nero himself.’

Not having heard him mixing his metaphors to the Revenue man, Sir Antony did not appreciate the allusion. Instead, he expressed his customary surprise at finding himself in this position and began as usual to find the reason, before exerting himself to get up. With the assurance of one who has just discovered a great truth, he announced: ‘D’you know, I have an idea. The second bin is stronger than the first.’ The excuse found and not contradicted, he crawled back under the table, found his wig and reappeared again with: ‘What’s the time?’

‘You’ve had your usual hour’s nap, Tony,’ said Doctor Syn.

Again this appeared to surprise Sir Tony. ‘The devil I have. Did I snore? D’you know I had a most remarkable dream. Dreamt I was at one of her ladyship’s putting parties – on the lawn. I was partnering the Bishop’s wife and she kept fouling my ball. So I tu-quo-qued her and she turned into the Scarecrow, and I found I’d got no clothes on. Damned silly when you come to think of it.’

‘Well, Tony,’ replied the Vicar, still regarding him with amusement, ‘while you were – er, partnering the Bishop’s wife, the new Revenue man paid me a social call.’

‘The devil he did,’ said Sir Antony, putting on his wig and slowly getting to his feet. ‘Thought I heard voices. Thought it was Lady Cobtree agitatin’ me to put me breeches on.’ Then the full truth of what Christopher had said dawned upon him.

‘What?’ he shouted. ‘Revenue Officer at this time of night? What did he want? Why didn’t he come to me? New man, eh? Doesn’t know the ropes. Should have come to me. Suppose he thinks I can’t keep order. Suppose he was criticizing my jurisdiction. Damned unfair. Mean advantage. Me, standin’ there shiverin’ with nothin’ on.’ His dream had evidently been so vivid that he was still in it, and Doctor Syn, knowing of old that his friend was like to become quarrelsome if not placated, said in all sincerity: ‘Now really, Tony; you should have heard the things he said about you.’

The Squire was mollified, having taken this to mean that the Revenue man had paid him compliments, which was indeed Doctor Syn’s intent; and so, after saying that no doubt the Revenue man was a damned decent fellow, he sat down comfortably in the chair from which he had so ignominiously fallen, and good-naturedly resumed the conversation with: ‘What was I sayin’ when I slid off?’

Doctor Syn explained that his last words before disappearing under the table had been to ask for another drink. The Squire received this news with as much interest as though he had delivered a pearl of wisdom, adding that he might as well have it now. Then in an attempt to pick up the threads of their interrupted discussion, said that as far as he could recollect, he was being annoyed about something.

‘Now what was I being annoyed about?’ he asked himself. Again, the bruises of the morning reminded him of his misfortunes, and after a lengthy grumble, in which there figured prominently the faulty bell-pull, the remains of Gabriel Creach, her ladyship’s bad temper, the waste of a good day’s sport, that confounded doormat bitin’ his toe; and then making that ridiculous offer of a thousand guineas for the Scarecrow who won’t be caught, this gave him another hint and he remembered what he was being annoyed about, and said triumphantly: ‘I know. Those fumblin’ old Lords of the Level askin’ the Dragoons to come and catch our Scarecrow. Read it in the papers. Lots of elephants tryin’ to catch an eel. Damned silly. Know perfectly well, no smugglin’ in this part of the country.’ Even that did not satisfy him as being the real cause; so he started again: ‘No, what was I bein’ annoyed about?’ Another ray of hope: ‘Oh, I know. That confounded highwayman, stoppin’ the Dover coach with me wife’s Aunt Agatha. Must have been Gentleman James because of his good manners. Damned bad manners, I call it, takin’ the diamonds old girl plannin’ to leave Cicely.’ Cicely. At last he had found the real cause of his annoyance, as is often the case, the chief worry having been obliterated by the trifling ones, and his voice now took on a sincerely worried tone. ‘That’s what I was annoyed about, Christopher – Cicely and Maria. Bad enough to have a daughter in France; all those upstarts cuttin’ people’s heads off all over the place – then Cicely goin’ off and not sayin’ where she was goin’. Said she was goin’ off to stay with the Pemburys, but she didn’t go there. And just when I want you most you go off preachin’ in London, and only return yesterday. No, I’m worried, Christopher.’

Doctor Syn urged that there was really no cause for anxiety, pointing out that Cicely was well able to take care of herself; that she had probably changed her mind about the Pemburys and had gone to stay with other friends; that probably she had written, but that the mails were unreliable.

The Squire, always influenced by what Christopher said, was only too eager to be cheered up, and so saying that Christopher was probably right, he asked for a drink.

Thinking that his old friend had already drunk more than was good for him, Doctor Syn said he was extremely sorry but that he couldn’t oblige, adding apologetically: ‘We made rather a night of it, you know. Even my small cellar will need replenishing.’

The Squire was most upset at this and asked him why the devil he had not said so before. ‘Here we’ve been sittin’ about, talkin’ and shiverin’.’ All his old grievances came back with a rush and he sneezed violently, announcing, as though it were a Christopher’s fault: ‘There, I knew I’d catch a cold on that lawn.’ There was only one thing for it. They must go home and open another bin. And in order to carry out this excellent idea he went with all possible haste to the front door, and, flinging it open, found that his way was impeded, for there on the doorstep were two large casks. Annoyed at not being able to get out, but equally mystified as to why such things should be outside the door instead of in their proper place, he reminded Christopher that he had said there was nothing in his cellar.

Doctor Syn remarked that there was nothing in his cellar but there certainly seemed to be something on his doorstep, which gave the Squire a brilliant idea.

‘I say, Christopher,’ he whispered. ‘P’raps they’ve left them. You know who I mean. They.’ Then, not liking to admit to the possibility of their existence, he mouthed the word ‘Smugglers’.

An even better thought then struck him. ‘Come on, Christopher. Let’s bring ’em in.’

Doctor Syn, however, seemed doubtful, suggesting that this was a matter for the Revenue man, at which Sir Antony was highly indignant, saying that he didn’t like the Revenue man anyway, and that he would handle this himself, and that it was a very good thing, since they could have a drink now, and wouldn’t have to wait till they got home.

So, telling Doctor Syn in his best judicial manner to report this to him in the morning, he set to work pushing and pulling at one of the barrels, speculating the while as to its contents.

‘Hope it’s not rum,’ he grunted; ‘don’t like rum. Her Ladyship can always tell.’

After a deal of struggling, in which Mr. Mipps had been summoned to assist, both barrels were successfully manœuvred into the room, and at the Squire’s orders the door was closed to prevent anyone ‘pryin’ in while he was investigatin’!’

Heated from his exertions, he could hardly wait to tap the barrels, and Mr. Mipps having conveniently produced a spigot with the necessary implements, he was delightedly setting to work when he noticed some roughly chalked writing on the side of the casks.

‘Hallo, who’s been chalkin’ on our barrels?’ he cried.

‘Looks as if they are your barrels, sir,’ said Mr. Mipps, who was on his hands and knees peering at the writing. ‘This one says “For our Parson with

C.O.M.P.S. from Scarecrow”. What does this one say?’ Mr. Mipps crawled round to the other. ‘“For our S.Q.U.I.R.T.” Squirt? ’Ope that don’t mean you, sir.’

Preferring to receive the insult with the barrel rather than without it, the Squire replied indignantly that of course it meant him. ‘Bad spellin’ – that’s all,’ and added that it was a waste of time standing about spelling when they might be drinking, and that for his part he was going to open his right away.’

At that moment there was a loud knocking on the door while from outside came what were obviously noises of the military. ‘Confound it, Christopher,’ grumbled the Squire, his thirst thwarted, ‘why can’t you have your callers at the proper time?’

Mr. Mipps, already at the spy-hole, whispered dramatically: ‘It’s the Dragoons, sir.’

Sir Antony, fearing that the Law might cheat him of his drink, asked Mr. Mipps to tell them to go away. ‘Never asked ’em here. Tell ’em to go home.’

This seemed easy enough till the full horror of the situation dawned upon him. Here he was, the Chief Magistrate, receiving smuggled goods. ‘Damned embarrasin’.’

‘I think we had better find out what they want, Tony,’ said Doctor Syn calmly. ‘The door, Mr. Mipps.’

Sir Antony, nearly crying with vexation, endeavoured to disguise his own barrel by draping himself round it, then finding that he was still holding the spigot, he endeavoured to hide such incriminating evidence, trying first one pocket, then another, and finally sticking it up his waistcoat, where it bulged most uncomfortably. By this time the door was open and Major Faunce and his Sergeant had come in.

‘I beg your pardon, sir,’ said the Major, addressing Doctor Syn, ‘but I was told I should find Mr. Hyde at your house.’

Doctor Syn greeted the soldier pleasantly and told him that Mr. Hyde had been gone for some little time. Then seeing that both the soldiers were caked in mud, he asked innocently if they had been fighting. To which the Major replied that ‘paddling’ would be a better description. He sounded and looked most aggrieved, explaining that they had been up to their necks in mud; in and out dykes halfway round Kent, and that he was positive monkey business had been going on with the signposts; that he had lost his men all but two, in this confounded mist, and hadn’t seen a sign of any smuggling; and it was all the fault of that meddling fool of a Revenue man sending them off on a wild-goose chase. He then apologized for his outburst, adding that that was why he wanted a few words with Nicholas Hyde.

Doctor Syn was most sympathetic, and remarking that the Major certainly seemed to have had a trying evening, asked him if he would care for a drink, while the Squire, who had been endeavouring, behind the Major’s back, to hide both himself and his barrel beneath the window curtain, and indeed had nearly succeeded, inwardly cursed Christopher for a forgetful fool, and made frantic signals in protest.

‘Thank ’ee, Parson,’ returned the Major, cheering up at the prospect of good drinking in pleasant company. ‘Very civil of you.’

‘You look as if you could do with something stronger than Marsh water, eh, Sergeant?’ laughed the Vicar.

Major Faunce, thus relaxed, took a glance round the room, and perceiving the Squire in the shadow by the bow window, advanced to greet him, catching sight of the barrels as he went.

‘Good evening, Squire,’ he said, bowing formally, to which the Squire could not respond owing to the stiffness of his waistcoat. Perhaps it was the Squire’s embarrassment which prompted Major Faunce to give closer inspection to the barrels, and upon reading the chalked inscriptions he became grave.

‘So, gentlemen, I see that you have had other visitors here tonight besides Mr. Hyde and ourselves, and we sent off to the other side of the country – misled on purpose, I see. Nice little plot.’ He warmed to the subject as he recollected the discomfort to which the Revenue man’s stupidity had put them. But on second thought, was it stupidity? Duplicity might be the better word. Possibly Mr. Hyde was not averse to a noggin of smuggled brandy and a bag of guineas as a bribe, and he’d be in good company, too. Perhaps they were all in it, against him. So he said aloud: ‘I’m afraid this looks mighty suspicious, Parson.’

The Squire seemed a trifle over-anxious to explain, and as always when he tried to use his best official tone, he became involved and ended up lamely that he was going out when the barrels bumped into him and he couldn’t leave ’em there doin’ nothin’.

This time, however, Doctor Syn helped him out and tried to straighten the matter, saying: ‘I assure you, Major Faunce, we know nothing about it. We have had a quiet evening here discussing parochial affairs, and as the Squire has just told you, we found them in the doorway. Naturally, as Lord of the Level, he wished to make an investigation at once, and —’

‘Much to your surprise you discover they are addressed to you!’ interrupted the Major.

Doctor Syn replied that that was exactly what he was about to say, adding: ‘So you see, Major, we are jsut as much in the dark about it as you are.’

But the soldier, by now thoroughly suspicious, pursued the subject still further. ‘But you didn’t intend to remain in the dark as to what was in ’em, eh?’

At this the Squire lost patience and exploded: ‘Well, dammit, man, what did you expect us to do – stand and look at ’em? It’s got my name on it. Read it yourself. A gift’s a gift. That’s Law.’

‘A bribe more like, and that’s not Law,’ parried the Major.

After so many years together in wild adventure, there had sprung up between Mipps and his master a system of signalling that had become almost thought-reading. During the above altercation this had been put into silent action, which resulted in the most innocent-seeming interruption from Mr. Mipps: ‘Beggin’ your pardon, sirs, for interruptin’, but the Vicar asked me to remind him about Mrs. Wooley’s complaint.’