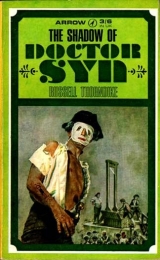

Текст книги "The Shadow of Dr Syn"

Автор книги: Russell Thorndike

Жанр:

Исторические приключения

сообщить о нарушении

Текущая страница: 10 (всего у книги 16 страниц)

One hour later Miss Gordon’s French maid, who by now had become reconciled to this land below the sea, partly because it was in sight of her beloved France but chiefly because of the flattering attentions of a young groom, went tripping down the village street, Mister Pitt at her heels and two large envelopes in her hand.

As usual, after a certain tune had been played and whistled, no one seemed to be about. Indeed she passed but two people, the first of which, a large woman who in passing her muttered audibly, ‘Goodness, there’s that foreigner! What is Dymchurch coming to?’ – the second, none other than Mr. Mipps, who was locking up his coffin shop, who exclaimed, ‘Why, if it ain’t that there yew-hedged poodle!’ Sweeping his battered three-cornered hat with a flourish, he bowed to the enchanted Lisette, who felt that ‘Marsh’ after all was not so dull, since here was that nice little man whose master had told her not to worry about the Scarecrow. After a deal of excruciating French from Mipps, and much twitterings from Lisette, she gave him the two letters which he promised to deliver – ‘toot sweet’, and hurried back to the stables in hopes of half an hour’s flirtation with her groom.

Mr. Mipps found Doctor Syn was in his library, studying a large map of the Continent. The sight of his old Captain measuring mileage with dividers caused the Sexton to ask hopefully: ‘What yer doin’? Looks like you’re planning to set sail again. Not thinkin’ of ’oistin’ canvas, are you, sir?’

The reply was not what he had expected, having playfully asked the question so many times, and received curt ‘Nos’ or ‘Remember to forget, Mr. Mipps’. This time, however, the calm, ‘Yes, Mr. Mipps – tonight’, made him execute a few well-chosen steps from his intricate hornpipe, until the Vicar’s shattering, ‘Alone, Mr. Mipps, and not what you’re thinking,’ brought him back to earth again, and with a long face he listened to the Vicar’s plans. He brightened, however, as the scheme unfolded and he saw fun ahead, and by the time Doctor Syn had finished he was himself again – full of admiration for his master’s daring idea, as, finishing the hornpipe from where he left off, he took the proffered glass of brandy and drank success to this new enterprise. ‘That’s the best one I’ve heard yet,’ he said. ‘Wish I was a-goin’ with you. Now then, what’s me orders?’

‘To begin with, Mr. Mipps, what ships lie in Rye harbour, ready to sail?’

Mr. Mipps not only had them at his finger-tips but rattled them off – friendly vessels and otherwise – and the Vicar made decision on the Two Brothers. ‘For,’ said he, ‘she’s fast, well armed, and I like her owners and her crew. Get word to them that I shall be aboard before high tide tonight. Tell Jonathan Quested to be at Littlestone with his fishing-smack at dusk. He must sail me round to Rye, for I shall be staying there in my capacity as Dean to visit neighbouring parishes, and will, of course, inform Sir Antony. I shall want you to deliver some letters for me. The one addressed to Captain Foulkes which I shall date the day after tomorrow must be handed to him at the Red Lion on the same day. ’Tis an invitation he is looking for to meet the Scarecrow, though I do not doubt that he will meet more than he bargains for.’ Then, turning away from Mipps and looking in the fire, he took up his pipe and said almost too casually: ‘The other letter I want delivered tonight, when I have gone. ’Tis to Miss Cicely, explaining why I cannot ride with her tomorrow morning.’ He looked over his shoulder and met the Sexton’s quizzical gaze; grinned boyishly and said, ‘’I am to have my first jumping lessons on a proper horse. I fear that I shall never clear the broad dyke as she can.’

‘Riding lessons,’ snorted Mipps. ‘Serve you right if you falls off. Jumpin’ lessons. You. From a petticoat. Talkin’ of petticoats, I met that French bettermy1 one. She gave me these,’ and he took from his pocket the two large envelopes Lisette had entrusted him with. ‘This for the Rev. – that’s you. And this for a Mr. Bone – don’t know who he is. There’s somethin’ in it, too.’

‘Ah,’ nodded Syn, not without amusement. ‘Our Jimmie has made a conquest indeed. I rather think she has returned his compliment. Perhaps this will explain,’ and he opened his own letter, noting with pleasure the large firm hand so full of flourishes and character, and smiling as he read the contents.

November 14th, 1793. The Court House,

1 Marsh word meaning ‘superior’.

Dymchurch.

My Dear Friend,

As I have every intention of becoming eighty upon the 19th of this month, I wish to celebrate it, and have commandeered the Court House for a party, which would not be complete without you. Indeed I shall be desolated if you fail, for I fear my only other beau will not be able to attend (I’d give my wig to see our Tony’s face if he did). I have writ him an invitation and returned his compliment with a token, so would be mightily glad if you, with your knowledge of black sheep, would see to its delivery. Cicely seemed so chagrined at the loss of her glove that although she carries it with her all the time, I had to give her some diamonds to make up for it. I shall insist that she wears them at my rout at the risk of losing my last remaining beau, so pray do not disappoint us.

Yours affectionately,

AGATHA GORDON.

P.S. – On second thought I have also writ an invitation to the Scarecrow, which I hope you will also be good enough to see comes to his hand, i.e. black sheep. For knowing that poor Caroline’s choice of gentlemen leaves much to be desired, and that I shall have an especial bunch of ‘party’ cronies for my amusement if I am not careful, so am leaving nothing to chance. I am going to be eighty but I am equally determined to enjoy myself.

A.G.

Doctor Syn appreciated the letter, knowing what the old lady meant by her innuendoes. He smiled when he thought that the old lady had noticed what the Squire and Lady Caroline had missed and would never dream could happen. So, telling Mr. Mipps to see that Jimmie Bone’s letter was delivered safe at Slippery Sam’s, with some added instructions that made the little Sexton howl with delight, he went to his desk and penned a grateful acceptance to Miss Gordon, saying that although he was going away for a few days on a decanal tour, not even the Archbishop of Canterbury would keep him from her party.

He left Cicely’s letter to the last, although it was the shortest, reading thus:

Cicely,

I am going on a visit with my younger brother. Pray do not worry, for I shall be back in time to compare your eyes with Miss Agatha’s diamonds. It may interest you to know that I am not jealous of my brother – I have an idea that I am younger than he is.

CHRISTOPHER.

P.S. – Pray inform your father that I am gone across the Kent Ditch. ’This his fault. He should never have made me the Dean of Peculiars.

Mr. Nicholas Hyde had spent the morning in the town of Rye, mixing business with pleasure in its many taverns. He had learnt, after some expense laid profitably out in strong ale, that the shepherds and cowmen were in league with the smugglers and were used for passing messages swiftly. This special code, invented by the Scarecrow himself, evolved a complicated manipulation of livestock – the position in a certain field of a particular animal meaning some keyword. Some three hours later Mr. Hyde, in his capacity of Revenue Officer, put this valuable information to the test.

Standing on the bridge across the Kent Ditch, which commanded a good view of both counties – Kent and Sussex – it certainly seemed that something was afoot; for what he saw was not the ordinary shepherding of flocks.

In a field close at hand he noticed that seven sheep were separated and put into the next field – a little further on a white horse was moved from one side of a field to another – while two black cows and a goat in kid were put into that same field. Turning, he saw the same thing happening about a quarter of a mile away. Then on again, and on, and so the message flew, till on the Harbour Quay at Rye the captain of the Two Brothers gave orders that his crew and vessel must be ready to sail on the next full tide.

So that in the language of the smuggler shepherds:

At seven sheep punctually a white horse stepped aboard the Two Black Cows, which sailed at the next goat-in-kid.

Chapter 16

Citizen L’Épouvantail not at your Service

Paris – and dusk already falling on another day of bloody entertainment for the mob. This was the Reign of Terror, reaching its peak but a month before, when the head of the beautiful Queen, the hated Autrichienne, had rolled into the basket. That was a feast indeed, and appetite whetted by the blood of royalty became voracious for any food that bore the faintest resemblance to the once powerful class they loathed and used to fear. And so the knife fell day after day, filling the baskets beneath that ghastly symbol of their age. Still their hunger was not satisfied, though the supply grew with the demand, for as the number of highly born showed signs of dwindling, these human vampires fastened themselves on any who bore traces of gentility, denouncing friends and enemies alike. A powdered wig, a jewelled snuff-box or dainty heel beneath a silken gown, any of these enough excuse for Madame Guillotine.

‘A bas les aristos! A la lampe! Vive le Republique! A bas la tyrannie!’ Yet enflaming the populace still further and committing more atrocious crimes of treachery himself was, strangely enough, a man of outward refinement. In the sadistic release of their pent-up fury, the newly founded citizens did not realize that these pale, proud, foolish aristos who, smiling, disdained the knife, had never been so tyrannous as this one man – Maximilien Marie Isidore Robespierre. All-powerful, Robespierre alone could still affect the powdered hair and exquisite clothes he condemned and was abolishing. This ruthless tiger preserved the dress and demeanour of respectability. Reckless, yet devoid of passion, greedy of blood, yet his private morals irreproachable. Politically courageous, though physically an arrant coward. Such was the tyrant of the day. He stood, this evening, at a window overlooking the Place de la Revolution as the final tumbrils jolted quickly to unload their offerings to Madame Guillotine before the dark. Rumbling and creaking they crossed the Pont au Change, along the Rue St. Honoré into the Square before him. A dripping November fog hung over the Seine, but could not damp the enthusiasm of the crowd, as from windows, parapets, roofs and leafless trees they watched this free amusement. As in turn each well-dressed actor made his first appearance on this grisly stage, the hush of anticipation changed to wild applause when he took his final curtain in the grim comedy of La Guillotine, the most popular actress in Paris.

Suddenly there was a disturbance from the back of the crowd: a latecomer elbowing his way through the screaming red-capped women who shouted greetings and tried to detain him. ‘Vive L’Épouvantail!’ they cried, but he pressed on, reaching the other side of the Place, from whose houses hung the tricolour banners of new France.

He passed beneath the window from which Robespierre looked, dived down a side street and knocked at the postern door.

He was admitted immediately, for he was expected, and conducted to an upper room, where a man stood waiting for him. Robespierre turned from the window, greeting him with, ‘Welcome, Citizen L’Épouvantail,’ then, with a wave of his hand towards the window asked, ‘And how does this organization compare with yours? I see your popularity here almost rivals mine, which sets me wondering what my reception will be in England when our system of Liberté and Egalité spreads to your country. But of that later.’ Motioning his visitor to seat himself, they went to the long table upon which stood wine and glass amongst a mass of papers, documents and maps.

Robespierre filled a glass which he handed to his guest and then poured a little for himself which he diluted with water. The Scarecrow’s mind worked quickly. Behind his inscrutable mask he smiled cynically. Here was a man guilty of spilling the blood of thousands of his countrymen yet afraid to taste the full-bodied wine of the country he had plundered. He waited to see if the man himself would prove as weak as the wine he drank, knowing full well he could afford to wait because of his own strength. Having thus summed up his character, a vain and mediocre man, he found it tallied with the outward show.

Robespierre, though not a dandy, was dressed fastidiously. A well-cut velvet coat of claret colour, white knee-breeches, stockings to match, all these the finest silk, while the large cravat and exquisite lace at his wrists proclaimed the salon and the boudoir – but not the bloody scaffold. Rising from a studious forehead, his hair was brushed back neatly and well powdered. His face, though capable of striking terror to his unfortunate victims, seemed to the Scarecrow to be the face of a clown with its tip-tilted nose and protuberant eyes.

Robespierre, scrutinizing in his turn, making little of what was before him, apart from fantastic clothes, and irritated that he could not see his opponent’s eyes and brow and so gauge the character of this man with whom he hoped to have dealings, politely requested him, since he was in the presence of a friend, to lay aside his mask.

To this the Scarecrow shook his head. ‘Your pardon, citizen,’ he said, ‘that I cannot do, for ’tis my bargain with Gehenna that when I wear these clothes and ride with the black devil, it is not meet that any man should look upon the blasted face of Sin. Believe me, such an evil sight would be distasteful to a gentleman of obvious refinement like yourself. No man unmasking me could look and live to tell what he had seen.’

‘Then keep your mask, citizen, for I am not experimenting. I have no inclination to be thus blasted into hell before my time. But come, let us to business. Barsard has worked swiftly, I see. Your request last night for an interview was sooner than I expected. He told you of my plan? Well, what do you think of it?’

‘Since I do not know your Barsard, citizen, he could hardly have told me of your plan.’

‘Then why are you here?’ Robespierre sprang to his feet and put out his hand to seize a bell upon the table. But the Scarecrow’s hand was already there, as with a note of irony he said, ‘Do not fear, citizen. I beg you not to be alarmed, although perhaps it is excusable. This meeting, I assure you, is entirely my idea. I also have a plan. It is a strange coincidence, this – each having a plan and thinking of the other. Now which shall be unfolded first – yours or mine?’

Robespierre had been plainly agitated on hearing that this man knew nothing of his agent. Then why was he here if Barsard had not sent him? Was it assassination? Since July the thirteenth, when Marat had been struck down, he had been haunted by the dread of sudden death. Had he not stood with Danton and Desmoulins hoping to see on Charlotte Corday’s face what fanaticism looked like, so that he might know it when he met it? Was it even now behind that mask? Was this the reason for the mask? Was it even now upon him? And so he remained standing, his own face now resembling a death’s head mask, from which his eyes alone showed life. But the Scarecrow spoke again. ‘I beg you, citizen, compose yourself. I assure you I have no designs upon your life.’ Then, as the cheering of the mob outside grew louder, he waved his hand in the direction whence it came and added: ‘You and I, citizen, have no need to resort to those methods, for I am here on your account as well as on mine own. But who is this Barsard? It seems I am indebted to him for this meeting.’

The Revolution leader seemed to be reassured and sat down once more in the gilt chair which seemed so out of place in this great empty room. He did not speak, but poured himself another glass of wine, this time without the water.

The Scarecrow, watching his reactions, was amused. It was so exactly what he had expected, and to satisfy the other’s curiosity and put himself in a stronger position, he assumed the air of a man who is about to put his cards on the table.

‘Since I have the idea that your plan may be similar to mine own, I will unfold mine first,’ he said. ‘I am not so modest as to assume that you have never heard of me on both sides of La Manche. You must know then that my organization is vast and unassailable. The fleet I have built up is well-manned and easily manœuvred. In fact the only thing that crosses the Channel safely is my contraband. I have lived, as you know, for the people, and my love for my countrymen is England is as great as yours for the people of France. Therefore I come to place myself by your side. Together we can do much.’

Robespierre was amazed. His great eyes protruded still further, as, thumping the table, he said excitedly: ‘But, citizen, that is my plan! ’Tis almost as though you have come straight from Barsard. I told you of my hopes that Liberté and Egalité would spread. Together we could make it spread to England. Keep running the blockade; you shall have every assistance on my side. Keep sailing with your contraband, but give me constant passage for my agents, who can spread our ideas of freedom in your land.’

He leant over the table eagerly and, taking up a dossier, he showed the Scarecrow the names of six of his best agents, who already had their orders. They would, he said, throw the country into confusion, and if more were sent every time there was a run of contraband, very soon they would achieve their object. He had already perfected a plan to overthrow the Government, the monarchy and that sacré English Pitt. With the unfolding of his plan his face too became the face of a fanatic, so infatuated with his own inspiration that he did not notice that his visitor had laughed. For indeed the Scarecrow could not suppress it as he had a sudden vision of another Mister Pitt, and of what Miss Agatha would have to say to that.

But Robespierre, now intoxicated by his own conceit, gave full rein to his imagination, and painted such a fabulous picture of a united republic with himself as head that the Scarecrow marvelled at the man’s audacity.

Robespierre went on: ‘Your ships are fast, my men are ready, our tide is at the flood, so let us take it. Without your help this plan collapses. When can you sail?’

‘Immediately!’ The Scarecrow’s prompt decision pleased the madman, little thinking that the masked smuggler had already formed a plan as mad as his. Robespierre showed promptness too. To augment the dossier in the Scarecrow’s hand, he found six others, each proving what a hold he had upon these trusted agents. Damning evidence, indeed, were it to be produced against a spy by England now at war. On that score, however, Robespierre had no qualms. Agents were well paid. If they were caught they knew the consequences, and took them. What he had already learned about this citizen L’Épouvantail assured him that such a man with everything to lose would never range himself upon the side of a Government that had put so high a price upon his capture. No, the English Crown would pardon any of the Scarecrow’s men who turned King’s Evidence, but for its very dignity could not be tolerant towards the man himself. His defiance of the Law had been too flagrant. This was one English rogue that Robespierre knew he could trust, and as he listened to the rascal’s chuckling over the descriptions of the spies, the arch-schemer was satisfied that this agents were in safe hands.

Details were then arranged. Three of the men would meet him at the Somme. The other three would ride with him from Paris, and, much to the Scarecrow’s satisfaction, Robespierre penned a letter empowering the Citizen L’Épouvantail to commandeer whatever form of transport he required. For him all Barriers were to be open without examination, no one was permitted to unmask him. In short, this citizen rode on the Republic’s business and was neither to be hampered nor asked inquisitive questions. Robespierre’s signature sufficed.

‘’Tis well to know the background of the lives of people you work with,’ remarked the Scarecrow as he placed the documents in his breast pocket. ‘There is but one thing more, I think. How do I get in contact with this Barsard, since he is already over there? In case of a mistake which might prove fatal to our schemes, I must ask you for his dossier too, for whatever credentials he may offer, I shall feel safer if I can put questions to him – dates, places, any fact that he must answer in detail, so that I can know he is your man.’

Robespierre nodded and went to a cabinet, as he answered: ‘I rejoice to see that my Lieutenant-General in England is so thorough.’ He selected a paper and handed it to the Scarecrow, adding: ‘There, citizen, read this with the others at your convenience. You will find there a most original career – a character that you would hardly credit in fiction. He is a man I should not choose to be an enemy.’

The last drop of the Knife for that day sounded outside the window, and a howl of enthusiasm mixed with disappointment that the curtain had fallen. The Scarecrow jerked his head in the direction. ‘The Citizen Robespierre has a quick answer to any enemy. I think you need not trouble yourself on any such score. I will now leave you this promise – that you shall hear of quick results upon this matter’ – and he touched the outside of his breast pocket in which the papers were concealed. ‘And what you hear will make you say, “That Citizen L’Épouvantail accomplishes all that he sets out to do”.’

Then, after drinking a toast to the success of this same citizen, Robespierre graciously accompanied his mysterious guest as far as the postern gate.

Having me the three who were to ride with him from Paris at a little tavern off the Rue St. Honoré, and in which a good dinner was served, the Scarecrow ordered the others to mount and await him, for he had a little private business of his own to attend to with the proprietor, who for many years had been one of the Cognac procurers for the contraband supplies. This merry rogue, after receiving his next order, whispered: ‘Two of those Robespierre agents are but dull dogs, citizen, bred in the Paris sewers until they saw there was a profit in being able to speak the English tongue. Oh, they’re useful enough, if throats are to be cut, but their intellects are not enlightening. The other is a different proposition. He was once a favourite at Versailles. Amusing. He will make you laugh.’

‘Robespierre has told me of him,’ chuckled the Scarecrow. ‘A pleasant-spoken rascal. I think you’re right. No doubt his history will make me laugh.’

It was this Citizen Decoutier whom the Scarecrow chose to ride beside him, while separating the others to prevent them talking, one ahead to rouse the Barrier guards and one behind. Decoutier certainly was amusing in a grim fashion, but his humorous anecdotes, in which he figured as the central figure, proved him to be a most depraved and despicable character. Indeed the Demon Rider of Romney Marsh could not have been accompanied by three worse fiends had he been the very Devil himself, and when they reached the rendezvous on the banks of the Somme the other three proved every bit as evil. This, as it happened, did not distress the Scarecrow. He was glad of it. It made his plan the easier to carry out. Though when he met his own Lieutenant, the engaging giant Dulonge who organized the fleet of luggers from the secret harbour on his own territory, the Scarecrow confessed that it was good to drink good brandy with another rascal who could lay claim to an honest humanity.

The Scarecrow found that the Revolution had not changed this old friend of his one whit. Like Robespierre and Decoutier, he did not fear to show he was something of a dandy, but in his case no one could criticize, for his huge frame carried an arm that could kill an ox, and such strength could never be concealed beneath lace ruffles.

To him the Scarecrow unfolded Robespierre’s plans and his own. He agreed on every point. They went together to the quay and made arrangements with the captain of the Two Brothers to take the six aboard and feed them, Dulonge vowing he would not spoil his own appetite by sitting down with such villainous characters. ‘For,’ he cried, ‘they all look as though they would rather eat their own grandmothers than my good saddle of lamb.’ The two friends sat down alone, and over their meal served in his spacious ancestral dining-hall they planned their future policy and how to pass quicker news of the movements of the ships of war so active now in the Channel. Certain of one thing, however, that so long as Robespierre’s interests were served their lugger fleet need have no fear from the French Navy.

After this meal they both went to the prison building on the quay, where Pedro welcomed Doctor Syn. Here were housed all those traitors who at some time or other had tried to betray the Scarecrow. ‘I think friend Barsard will not lodge here,’ said Dulonge, ‘for you will deal with him, and if he comes my way I’ll silence him.’

The Two Brothers was ready for sea, and the Scarecrow, after a farewell to Dulonge and Pedro, went aboard, and the voyage began. At the mouth of the river a shot was fired across their bow by a French frigate, and at the Scarecrow’s order the captain hove to and allowed an officer to come aboard. ‘No one may leave home waters,’ said this officer. ‘The British fleet is out and our ships will give battle.’

‘Cast your eye on this, my little citizen,’ replied the Scarecrow, showing him his passport from Robespierre. ‘The arm of La Guillotine can even stretch to sea, as any of your officers will find who hinders the Two Brothers. Tell your captain to put to sea and keep the English from us.’

The officer apologized profusely. He hoped indeed he had not detained the Citizen Captain, who sailed in the Republic’s interest, and he was rowed back to his frigate, where he did not scruple to frighten his captain with what the strange L’Épouvantail had said about La Guillotine.

This incident showed the Scarecrow that so long as Robespierre was all-powerful he had a letter of safety from the French. His only fear of serious interception was therefore from the British. In spite of his secret plan he realized that the presence of French spies aboard would look black for the captain of the Two Brothers and worse since the other passenger (himself) was a notorious malefactor wanted by the Crown. So on this voyage the Scarecrow decided not to be a passenger. He took the tiller. He took command, and in the dark hours before the dawn, no lanterns showing, he ran the gauntlet of a British line of men-o’-war. But these giants were watching for bigger fish to tackle than this swift clipper, that appeared and vanished like a ghost. It was the old Clegg that navigated the Two Brothers to Dungeness. It was here that the six Frenchmen huddled on the deck, close together for warmth, were badly frightened, for the Two Brothers was hailed in the darkness by a voice proclaiming the authority of the Sandgate Revenue cutter. ‘Name your vessel,’ cried the officer. ‘The Twin Sisters, fishing,’ sang back Doctor Syn. ‘We’ll come aboard, and see your catch,’ called out the officer. The Scarecrow had crept forward to the for’ard gun. There was a loud report, a flash of flame, and then the splintering fall of wood. He had unstepped their mast.

Over went the tiller, and the Two Brothers shot out again before the wind, tacked back and then, instead of landing to the west of the long nose of shingle, she crept into the Bay. The three hoots of the owl were heard and answered by the scrape of stones. The Frenchmen did not understand this, but the Scarecrow did. Twelve men, under the command of one called Hellspite, were hurrying across the pebbles with back-stays1 on their feet. The Two Brothers was heading for the land end of the Ness where the old Marsh town of New Romney nestled. Here the horses were ready, and six stalwart fishermen in masks carried the Frenchmen to the shore. They neither asked nor knew what men these were, except that they were landlubbers who feared to wade in the dark. Ashore all they saw in the swinging lantern light were six more Scarecrow’s men, just like themselves – hooded and masked.

‘Is all prepared?’ the Scarecrow had called across the few yards of shallow water from the deck of the Two Brothers.

‘Aye – aye. Hellspite here and horses ready,’ came the answer.

In a few minutes all were transferred from deck to saddle and then, following the Citizen L’Épouvantail, who had proved his loyalty to Robespierre by firing at a British ship of war, the grisly-looking cavalcade set off along the sea-wall road. Passing Littlestone they turned into the Marsh, and in and out the intersecting dykes they galloped. As they rode, the Scarecrow turned his charger alongside that of Hellspite.

Leaning down in the saddle, no one but Hellspite heard the whisper: ‘What of the Beadle?’

It was the voice of the Sexton of Dymchurch that answered: ‘It was too easy. I was drinkin’ with him. But he was out before I ’ad a chance. ’E ain’t got no ’ead for liquor, that there Beadle.’

‘And the keys?’

‘I got ’em. ’Angin’ on me belt. Did you fare well across there?’

‘Aye, Mipps – I’ll have a tale to tell you. At dawn we’ll crack a bottle.’ And the Scarecrow reined back and for a time rode with the Frenchman Decoutier.

They did not ride into the village of Dymchurch, but skirted it, keeping to the Marsh fields that lay behind the Church. Here they dismounted and, tying their horses to a sheepfold fencing, the Scarecrow whispered to the Frenchmen to walk in silence as they were near the end of their journey. He told them that he was taking them to his underground headquarters where there would be good food and drink, as well as security. As the way was difficult, he ordered each Frenchman to be supported on either side by his own men, and then they crossed a bridge and stumbled into the blacker darkness of the Rookery and at last down outside steps, where a door was silently unlocked by the little figure they had heard named Hellspite. ‘Prenez – garde – silence,’ warned the Citizen L’Épouvantail.