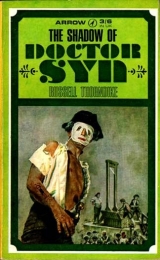

Текст книги "The Shadow of Dr Syn"

Автор книги: Russell Thorndike

Жанр:

Исторические приключения

сообщить о нарушении

Текущая страница: 7 (всего у книги 16 страниц)

The Vicar thanked Mr. Mipps warmly, as indeed he had forgotten all about it. He begged the gentlemen to excuse him, but he must ride out and give the old woman a few words of cheer and keep her in good spirits.

‘Then,’ said Major Faunce, intending not to lose sight of any possible clue, ‘you’ll not object to my sending a couple of my men with you, to see that her taste in spirits is not barrels of smuggled brandy?’

Doctor Syn replied almost gratefully: ‘Not at all, Major Faunce. On the contrary, I enjoy company on a long ride, and no doubt the poor old body will give them a glass of her parsnip wine for their trouble.’ Mr. Mipps helped him on with his long coat, and the Vicar thanked him, adding an extra benediction on his good servant for reminding him of his duties. Then turning to the Major he requested: ‘Pray, Major Faunce, do not fail to let me know what spirit those barrels contain. I must preach a very strong sermon against it next Sunday,’ and with the pleasantest of smiles he went out to mount his fat white pony, whilst the Sergeant gave instructions to the two troopers that Doctor Syn was to be escorted across the Marsh and watched, adding that in his opinion the Major had gone a bit too far, being suspicious of a poor old gentleman what was only doing his duty.

Indeed, the Major was at that moment thinking the same thing himself and feeling a trifle ashamed for having entertained the slightest suspicions about such a good and kindly soul as the Vicar of Dymchurch. If, however, he too had been able to read thoughts, he might have taken even stronger measures.

Chapter 11

More Compliments from the Scarecrow

Sir Antony was peeved. It was deucedly embarrasin’ bein’ left alone with this Faunce. It wasn’t like Christopher to let a fellow down, and he felt he had been left in the lurch. Indeed, the whole thing was Christopher’s fault, and it wasn’t like him to make mistakes. Why had he insisted on letting the fellows in? Easiest thing in the world to have sent them away. Could have told ’em the Revenue man wasn’t there. Yes, he decided that he definitely did not like that Revenue man. And here he was alone with Faunce and didn’t know what to say. The barrels were sittin’ there lookin’ at him. He’d got the devil of a thirst, and something was makin’ Mipps grin. Righteous indignation made him breathe more heavily than usual, as he punctuated each thought with a snort. Thus it was that the spigot became loosened, and during a mighty intake of breath which of necessity moved the Squire’s diaphragm, it fell with a clatter to the floor. Fortunately Major Faunce’s back was turned so he was able to kick it beneath the settee. He was so pleased with this manœuvre that he did not even notice that he had done it with his bad toe, but upon the Major’s turning round he decided that some explanation was due for the noise and the movement of his foot beneath the settee, and bethought himself of the Vicarage cat, knowing full well that it lived in the stables.

Making a series of jabbing movements with his foot as though inducing the playful animal to come out and chase his toe, he did some clicking noise with his tongue, and in the language usually employed when addressing cats he endeavoured to make his performance convincing. ‘Nice Pussy, then. Turn along. Puss, puss, buss.’

Once having embarked upon this course, he felt at a loss to know how to stop, and was about to go down on his hands and knees as further proof of its existence when Mipps came to his rescue by saying, in warning tones: ‘I shouldn’t, sir. She’s ever so spiteful.’

Straightening himself with a, ‘P’raps you’re right. N’other little family on the way?’ he gave Mipps a look of deep gratitude. Mipps, from a position of vantage, returned this with a confidential wink and a, ‘Yes. H’aint nature wonderful? D’you know, Squire, who I think it is this time? Mrs ’Oneyballs’s black Tom. ’Orrid cat. Roguish.’

The Squire, though grateful, felt that it really wasn’t fair of Mipps to pin a family of kittens on to Mrs. Honeyballs’s unsuspecting Tom.

Major Faunce wondered how he should next proceed, and, having discussed the matter in whispers with his Sergeant, had no mind to stay listening to kitten talk. He was extremely tired after two successive fruitless nights upon the Marsh, and in spite of the Squire’s presence, he determined to take charge. So approaching the barrels he said: ‘Well, Sir Antony, I suppose wwe had better get these over to the Court House and put in bond, and that will end my responsibility in the matter.’ Mipps, however, had other ideas upon the subject, saying he didn’t know how he was going to get ’em there, unless it were such good spirits as the barrels grew wings, and flew there. ‘I’d give an ’and myself only what with my gravedigger’s elbow I haven’t got a lift left.’

It was then that the Major realized that for once this odd little Sexton was talking sense, and he cursed himself for having sent his last two men with Doctor Syn, so he said to the Squire: ‘Egad, sir, the fellow’s right,’ and not wishing to admit his mistake, tried to cover it up with: ‘This is really the business of the Revenue man.’

The Squire saw his chance and pounced. ‘Well then, sir, let’s dispense with the Revenue and open ’em here – out of hand. ’Twill not be agains the law. Magistrate. Witness.’ He glowed with anticipation and thought it would serve Christopher right, too, for not being here to share. ‘Test it together. I give us full authority.’

Major Faunce agreed, saying that he didn’t mind showing Mr. Hyde that he could do his job a deal better than Mr. Hyde could his, and ordered the Sergeant to assist Mr. Mipps in opening the barrels. But Mr. Mipps needed no assistance. Indeed, he was there already, attacking the Vicar’s cask with the knowledge of an expert, when he suddenly stopped and said excitedly: ’Ere, where’s the bung-’ole? ’Asn’t go no bung-’ole. Something wrong with this barrel. Got a false top. ’Ope it ain’t goin’ to blow us sky ’igh.’

Mr. Mipps was nearly blown sky-high, for as he spoke the top of the barrel flew off and a pistol was presented at his head, as over the rim of the cask the head and shoulders of a girl appeared, three-cornered hat slightly awry. Dazzled by the sudden light she commanded them in ringing tones to put up their hands.

‘Haut les mains,’ she cried. ‘Vous-aussi. Les mains. Rendez vous tous.’

The hands of all four men had shot up in bewilderment as they stared at this wild little figure, hair a mass of tumbled auburn curls, her lovely face alight with fierce excitement, which, in the next instant, and upon astonished cries from Squire and Sexton, changed to an expression of surprise and wonderment as, looking quickly round the room, she recognized it. ‘Good Heavens!’ she cried. ‘’Tis the Vicarage. And we are not in France. Oh, Mr. Mipps, I thought you were a revolutionary rabble. Papa! Then we are safe. We are across the Channel. He did smuggle us, Papa. Don’t look so scared. ’Tis Cicely.’ The Squire, in his astonishment, had forgotten to drop his hands, and she continued, laughing gaily, ‘Pray drop your hands, sir. ’Tis Cicely.’ His fright and relief at seeing her turning to anger, he almost shouted, ‘Dammit, girl, what does this mean? Lud, Cicely, what a fright you gave me. Thought you were going to stay with the Pemburys. What do you mean, miss, going off without a word? What do you mean, miss, causing such anxiety? Damme, I shall need an explanation – I’m your father. Popping out of a barrel like a jack-in-the-box. In the Devil’s name where have you been, miss?’

‘Pray don’t be so cross, sir,’ she answered. ‘I can explain – I’ve been to France and I’m back.’

Sir Antony snorted. ‘France – what do you mean, France? Have you seen Maria?’ The girl’s expression changed again to one of apologetic humour. ‘Lud, Papa, I had almost forgotten Maria.’ And then with a wave of her gauntleted hand to the other cask she said: ‘She’s in there – and when we let her out I warn you, sir, she’ll start screaming again – but she’s had a terrible time, poor lamb. Lud, I can’t stand this barrel a minute longer. It smells like the Herring Hang. Dear Mr. Mipps, pray give me a hand.’ Mipps, who had been gazing at her in admiration, leaped forward to help her, but seeing that the pistol was still unconsciously pointed in his direction suggested with a grin that he should hold the artillery. With riding-skirt held high she scrambled out, straightened the green velvet folds, and stretched luxuriously. ‘Oh, it’s wonderful to be home,’ she cried. ‘But I am as stiff as a dead starfish.’

Major Faunce was also gazing at her in admiration. His soldier’s instinct told him that here was bravery. What manner of girl was this, who could talk so gaily of returning from an enemy country? He was curious to know what she had done and why. With approval he noted the determination in every line of her tall, almost boyish figure – her oval face was delicately cut, yet behind the large mischievous eyes there seemed to be a mysterious purpose. In spite of her youth, she had about her an air of authority. And with amusement he noticed how, impatient that the men were doing nothing except stare, she went swiftly, with easy graceful strides, to the other barrel and taking the command, ordered Mipps and the Sergeant to unfasten here and there, and to do this and that with: ‘Come, sirs – make haste. She’s been there long enough.’

Under her compelling personality, even the Sergeant came to life. Both he and Mr. Mipps acting as they would have done under a commanding officer, responded to her orders, and swiftly it was done.

The lid was off and as the Sergeant leaned over the rim to help the lady out, there came such piercing screams that he jumped back again, as a shrill little voice cried, ‘Get away from me, you great French brute! Cicely! Cicely! Where are you, Cicely?’

Sweeping the others aside, Cicely leant over the barrel and soothed: ‘All right, Maria. I’m here. We’re home. You can come out now.’

But the screams continued, and indeed grew louder. ‘Now, dearest Maria, don’t be foolish,’ calmed Cicely, and whispering to Mipps: ‘You see, what did I tell you? She’s been very vexing. Come out, my lamb,’ she coaxed, leaning into the barrel. ‘We’re in the Vicarage and here’s Papa.’

Up from the barrel leapt a distraught figure, a great travelling-cloak hiding the bedraggled finery of what had once been the height of Paris fashion. Her blonde hair, out of curl, hung limply round her tearstained face. A woebegone little figure, who upon reaching the floor through the arms of Mr. Mipps, rushed sobbing to her father. ‘Papa! Oh, Papa!’ she cried. The Squire put his arms about her and made a clumsy attempt to calm her. His awkward pettings and the embarrassment that most Englishmen feel at a show of hysteria were charming and endearing. But all his efforts were to no avail, as Maria let out the full force of pent-up self-pity. Determined that others should share the horrors she had been through, she plunged into lurid descriptions of how terrified she had been, of how Jean, her husband, had left her in Paris all alone in their great house, of how all those ugly people came and frightened her, and then how Cicely came and she couldn’t understand why she looked ugly too. She had sung and shouted and behaved in a horrid manner, and that dreadful man who had kept ordering them about – of how he had been half naked with a picture on his arm – a ghastly picture of a shark – tattooed, like sailors have, and how they had never seen his face because he wore a hideous mask, but that the crowd seemed to know him and like him too, because they did what he said and didn’t touch them, and everywhere he went they shouted, ‘The Scarecrow! Vive L’Épouvantail!’ Seeing that she was indeed holding the attention of her audience, she determined to vent some of her bewildered anger upon her sister, telling of how Cicely had actually appeared to enjoy it, and that the Scarecrow had paid more attention to her, because he had left them and made a special journey to get her riding-habit back, when she said she would look funny going back to England disguised as a French peasant. But she, poor Maria, had nothing but what she stood up in. She had lost everything. Husband, house, and all her pretty clothes. This made her cry so much that she could speak no more.

The Squire was quite desperate, with repeated, ‘There, there. No one’s going to hurt you. Your father’s here.’ He implored Cicely in God’s name to tell him what had happened, and what did she mean by all this wild talk.

Major Faunce, who up to now had kept silent, now came forward with a somewhat sinister question: ‘Yes, indeed. What does she mean? I shall be glad to hear an explanation.’

The Squire, who had forgotten all about the Major in this confusion, did not catch the tone of suspicion in the soldier’s voice, so he introduced his daughters, and looked appealingly at Cicely to help him out, which she did with, ‘Pray, sir, forgive our unladylike arrival at this evening party.’ Then, turning to her father, she said in a whisper loud enough for Major Faunce to hear, ‘Papa, pay no attention to Maria – I told you she was hysterical, poor pet.’ Then once again, but this time looking round the room, she changed the subject. ‘But where is your host? Where is our beloved Doctor Syn?’

The Major was quick with his reply. ‘He was called out to visit a sick woman. But I am afraid this is not an evening party, Miss Cicely. I am here on business. The only invitation we have had tonight is from the scoundrel whom your sister has just been talking about. In the King’s name, I must ask you to tell me more about this French Scarecrow.’

The Squire indignantly retorted to this: ‘Nonsense, Major Faunce. I’ll not have my daughters questioned at this hour, and after all they have gone through.’ Then added as if he had just thought of it: ‘Now, Cicely, child, tell your father all about it.’

Cicely went over to her father, and upon seeing that the dear soul was wearing the expression of a bewildered bloodhound, kissed him and asked to be forgiven for having caused him so much anxiety. But she explained: ‘You recollect how anxious we all were about Maria. I did not tell you I had planned to go and help her, for I knew you would not let me go. Oh, ’twas easy enough to get there. Bribes and a fishing-smack. And ’twas easy enough to get to Paris. All I had to do was to make myself the complete sansculotte and shout and scream with the mob. It was nothing. I know the language. Thanks to you, Papa. And as you know, I had friends there, though now heaven knows what has happened to some of them. As to the man Maria talks about, well, there were so many wild characters I fear she must be confused. Indeed, poor goose, she scarcely recognized me. There she was, cowering all alone in that great house. Hadn’t been out for days, all the servants fled.’

This awakened in Maria fresh memories of the departed glory of her married life, and she let out a howl of anguish. ‘All right, Maria my lamb, ’tis over now,’ said Cicely, who continued to talk with her father. ‘It is a terrible thing they are doing, Papa. We were forced to witness ghastly scenes. And all the time the mob was getting nearer to Maria’s home. We would have been in more danger had we stayed.’

All this was too much for the Squire. He just did not begin to understand what Cicely had been doing. Any more than he had understood why Maria had gone and married a Frenchman. All he could stammer out was: ‘It’s deuced confusin’. Two girls – alone. Someone must have helped you. Was it this French Scarecrow?’

Major Faunce cut in with: ‘Sounds more like our English Scarecrow to me. There’s his signature on the barrels.’

Cicely replied to this with spirit that since he had not been in France, how could he know anything about it? ‘Everyone in Paris these days looks like a scarecrow. They’ve all gone mad – wild. Scarecrow! L’Épouvantail! they all shout. But it might mean anyone. They might have meant me, for a looked scarecrow enough.’

‘They did not mean you, Miss Cicely!’ The voice came from the dark shadows by the front door. Harsh, impersonal, yet with a hint of humour, as it continued: ‘Your revolutionary clothes suited you admirably.’

All had turned suddenly upon the sound, and there was no mistaking who it was. There he stood, masked and mysterious, the dreaded Scarecrow himself – with two thousand guineas for his capture. No one could move, for he held two heavy pistols in his hands, and bowing said: ‘L’Épouvantail, at your service.’

This movement caused Major Faunce’s hand to fly to his belt, but the harsh voice rapped out: ‘Don’t move! I have you covered, gentlemen.’ And thereupon, seeing Mr. Mipps, who indeed appeared to be terrified, he ordered him to disarm the red-coats. ‘A wise precaution,’ laughed the Scarecrow, ‘since I see the Major’s fingers twitching to be at his belt. It would be foolish to disobey, and we don’t want to rob the Revenue man of the little surprise I have prepared for him. I must ask you, gentlemen, to oblige me by stepping into those barrels.’

Mr. Mipps had rapidly removed both swords and pistols from the soldiers, and at the moment resembled a miniature arsenal.

The Scarecrow spoke to him, ordering: ‘Here, you, little man. Assist the gallant red-coats into those convenient casks.’

A brave man, the Major’s first instinct was to refuse, but the Scarecrow went on inexorably: ‘Come, come, Major, if the ladies can use these to travel across the Channel, surely you will not mind a little trip along the sea-wall. Why, I envy you the experience of seeing Mr. Hyde’s face when he opens them. I dislike being kept waiting, Major. Make haste!’

There was nothing for it. The reluctant soldiers had to squeeze themselves into the barrels as best they could. Mr. Mipps having put down all the weapons save one, almost seemed to be enjoying prodding the Major in with his own sword, as with oaths and protests they disappeared, as Mr. Mipps, putting on the specially constructed lids, encouraged them to stay snug and have a nice trip.

The Scarecrow went swiftly to the door and opened it, calling three times the eerie cry of the curlew, and from the shadows came four masked and hooded figures. Upon swift orders from the Scarecrow they went to the barrels, waiting whilst he changed the wording on each, so that the chalked message now ran:

To Nick Hyde, Rev. Man, With Comps. From Scarecrow.

Then, lifting the barrels, they carried them to a covered cart that waited on the sea-wall. When all was ready to move, the Nightriders mounted their wild steeds and escorted the strange cargo swiftly and silently along the straight coast track to Sandgate.

Chapter 12

In which Cicely Forgets Her Gloves and Doctor Syn Forgets to Remember

Maria sat sulking – a forlorn heap – on the settle by the fire. She was tired and dispirited, with a head that throbbed from her cramped voyage. She was no longer the centre of interest and she resented it. Here she was, home and safe after her terrible experiences, only to find that the ghastly creature had followed them here. She couldn’t understand it. And what was more, Papa seemed to be amused, for there he was at the window laughing and watching the Scarecrow giving his dreadful orders. Maria felt that he should be paying more attention to his miserable daughter. As for Cicely – there she was looking as fresh as though she had just left her own bedroom at the Court House to go a-riding. Sitting astride the long, low fire-stool, in the most unladylike manner, she too seemed to be thoroughly enjoying it, looking up to the window and laughing. Maria could not laugh when she thought of that poor Major, and was annoyed because she would have liked to have seen more of him. He was really quite attractive; she wished she had not looked so dreadful. This thought plunged her into tears again, and it was then that the Scarecrow returned, closing the door, and sweeping them with a low bow.

‘I must apologize, ladies, for my somewhat crude sense of humour,’ he said, ‘but I fear I could not resist playing the eel to those elephants. You need your papers, of course, Sir Antony.’

The Squire looked surprised. Now where had he heard those words before? He tried to remember, but his mental efforts were interrupted by the Scarecrow saying: ‘May I express my gratitude, Miss Cicely, for your admirable attempt to keep my identity a secret?’

Cicely got up from the stool and went over to him boldly. Maria thought she went too close, and turned her head away disgusted.

‘It was the least I could do, sir,’ said Cicely in a warm tone. ‘And I might have succeeded had not this goose here blabbed all.’ She turned and entreated: ‘Papa, Maria, have you no word to say?’

Maria buried her head in a cushion. ‘I don’t want to speak to him. Papa, tell him to go away.’ And then, hoping for sympathy: ‘Oh, my poor head! ’Twas terrible, the discomfort.’

This did not produce the desired effect upon Cicely, who, with a show of spirit at her sister’s ill manners, said with some impatience: ‘Fiddlesticks,

Maria. The discomfort of a few hours is better than losing your head. Lud, miss, pretty though it is, ’tis sometimes foolish enough.’

The Squire, agreeing with Cicely that Maria should at least thank the gentleman, said that although he could not yet understand what had happened or what had not happened, he was naturally indebted to the Scarecrow for what he had done, but, damme, he was placed in such an awkward position. As Magistrate he ought to arrest him, at which the Scarecrow, bowing low, asked him if he would care to try.

Sir Antony, knowing that he had not a chance of doing so, blustered to hide his confusion and said that it would be a poor sort of gratitude. ‘And you, sir, know that, or you would not risk being here. But what I want to know is’ – and Sir Antony came to the point – ‘law-breaker as you are, what made you do it?’

‘Call it a whim if you like, sir,’ answered the strange creature, and he turned slightly towards Cicely, ‘though I am more pleased to call it my admiration for high courage. You have a daughter, Sir Antony, you could be proud to call son. Ask me how I knew of her brave venture? I have spies everywhere. Oh, call me what you will – rogue, scoundrel, rascal – aye, Sir Antony, even “smuggler”, but I have ever been in love with the gallant spirit of the Marsh.’

The Squire was beginning to understand. Cicely had done a brave thing. Indeed, she had done a generous thing too, for Maria had never been overkind to her. He warmed to his daughter, and he wished after all she had come and told him what she was going to do, though he knew in his heart of hearts that, being the clumsy fool he was, he would not have been able to help her. He warmed, too, towards this curious mystery of a man before him. He wished to ask him a lot of things, but all that came out was stammered in the usual tongue-tied fashion, that as Lord of the Level he appreciated his sentiments and admired his debt, and damme, admired his ingenuity, but it must have failed him lamentably this time if all he could think of was to send his daughters home to him in barrels. ‘Why the devil did you have to do that, sir?’

The Scarecrow laughingly explained, ‘Because, my dear sir, and I fear you know this is true, the one thing that always crosses the Channel safely is my contraband.’

Cicely went to her father and, putting her arm through his, told him not to worry about how they had travelled, since the important thing was that they were safe, and they had been in great danger. She pointed out to him that though it had been easy to get there for her, it was a different matter when they had tried to leave, because Maria was escaping and she was an aristo. ‘Oh, I know what you are thinking, Papa,’ she said. ‘Damme, sir, they would not dare to touch a Cobtree.’ Here she did such a perfect imitation of Sir Antony himself that even he had to laugh. But she went on seriously, explaining that they would most certainly have dared, that being a Cobtree only heightened the danger since she was an English aristocrat. Being that, of course, the teasing girl had refused point blank to disguise herself as she did in dirty rags, insisting on wearing her latest gown. Indeed they had been followed several times, and on one occasion had been recognized by a dangerous friend of Maria’s treacherous husband. They would have been denounced had it not been for their good friend here. This gentleman had seen to everything. Each time they were in difficulties he appeared. Their papers – the horses – the right word at the Barriers. Oh, she realized now that she could not have done it alone. Going to the Scarecrow, Cicely held out her hands. ‘How best can I thank you, sir?’ she asked. ‘It seems by imploring you to leave; each moment you remain is but adding to your danger.’

At last Sir Antony realized just how much this man had done for his daughters and the danger into which he had placed himself, and he said impulsively: ‘Ay, Cicely, you’re right. The place is littered with Dragoons, and I warrant that confounded Revenue man will not be in a pretty mood when he’s received your present. As my daughter says – the best way to thank you is to ask you to go. So go, sir, and good luck to you, and mind you don’t get caught or I shall lose my thousand guineas.’ Then pulling himself together – remembering that after all he was the Chief Magistrate, he added: ‘Though, mind you, tomorrow I shall have to put out another Proclamation for your arrest.’

The Scarecrow thanked him for his warning and said he would study the new Proclamation carefully – for his own neck told him that he had no wish to see Sir Antony lose his thousand guineas.

‘As to my leaving upon the minute – that I cannot, for I must stay here until the Vicar returns. I have to pay him my tithes. Tonight it will be a considerable sum, since my latest cargo was such a valuable one.’ The last remark was directed to Cicely.

Then, addressing the Squire, he suggested that the ladies must be in need of rest and it would be as well if he escorted them home.

Cicely had been watching him for some time, and with a curious little smile she asked: ‘Could I not stay? Above all things I should like to see a meeting between the Scarecrow and our Doctor Syn.’

‘I’m afraid I must disappoint you, Miss Cicely,’ he replied, ‘for this is business. Tithes are a tenth of what one is worth, so if you are good at reckoning you might too easily calculate my estimation of your value.’

The Squire, pleased to get back on familiar ground, said that tithes were tithes and all honest men should pay ’em; then realizing that he had said the wrong thing, coughed loudly and prepared to take his leave, waking Maria who was asleep upon the settle.

Bowing with a ‘Your servant, sir,’ he led the sleepy Maria to the door while Cicely, lingering behind, said with a look of amusement which failed to hide the alert expression in her eyes: ‘I am almost certainly going to ask our dear old Doctor Syn to stop preaching his horrid sermons against you.’

Then, turning swiftly, she followed the others and he was left alone.

Cicely crossed the bridge that led from the front door on to the sea-wall. She saw that her father was taking the short cut down the steps and across the Glebe Field. In her present mood she had no mind for more questionings. Nor, indeed, to be whined at by Maria. So she made no haste to catch them up. Standing for a while in the moonlight, she felt almost sad to be at home again though her instinct told her that she should feel differently, because what had made her happy in France was also here in Dymchurch. Her discovery filled her with an exultation she hardly understood. Turning, with her back to the sea, she faced the dark, familiar outline of the Vicarage, standing clear before the ragged silhouette of the rookery, while, brooding over all, the Beacon Knoll of Aldington. This shadowed sky-line seemed to come to life and claim her, as though at this moment it saw her for the first time, and beckoned to her.

And then she knew that she could find the answer to the riddle that it set, just as she knew that now she must follow where that answer led. So, challenging the shadows, she flung her gauntlet gloves down into the Vicarage garden. Then going swiftly down the sea-wall she raced across the Glebe and overtook the others.

‘So here you are, Miss,’ said the Squire. ‘Maria wanted to get home, and I knew if you could find your way to France and back you’d be abel to make the Court House from the Vicarage.’

‘I’m sorry, Papa,’ answered Cicely. ‘’Tis such a lovely night, and it’s so good to be home. I was on the sea-wall.’

It was when they were going through the Lych Gate that Cicely stopped. ‘Oh Lud, I do declare I must have lost my gloves. Now where did I drop them? I’ll run back and look, for they were such a lovely pair. I may have left them in the Vicarage. So you two dears go on. Do not wait for me.’ And so saying, she sped back again.

While Cicely was crossing the Glebe field for the second time, Mr. Mipps in his capacity of Parish Clerk was crossing the hall of the Vicarage with an enormous tome, marked Dymchurch Tithes. ‘The Tithe Book, sir, for your settlement with the Vicar.’ He spoke apparently into thin air for the room seemed to be empty. As he walked he elongated himself as if trying to make himself taller.

‘You seem to have acquired a stiff neck, Mr. Mipps.’ The voice came from behind the lectern. ‘’Tis not the Marsh ague, I hope? Or has your blushing ear been getting you into trouble again?’

Mister Mipps was all indignant, and snapped: ‘’Tain’t nothin’ to do with my inflamed ear, and I hain’t hacquired a stiff neck neither. I’m hendeavouring to hacquire a few hinches, halludin’ to me as if I was a dwarf. “Little man.” In front of others, too.’

He put the book down on the side of the lectern nearest to him with a slam, and in his own phraseology he ‘beanstalked’ acros the room to get ink and quill.