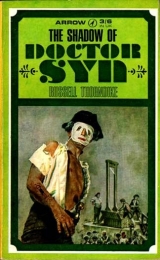

Текст книги "The Shadow of Dr Syn"

Автор книги: Russell Thorndike

Жанр:

Исторические приключения

сообщить о нарушении

Текущая страница: 15 (всего у книги 16 страниц)

‘Earshot,’ though Mipps. ‘Ear foxication,’ and he set to work in the next room to put this plan into action. By an elaborate system of knots, weights, and the clock’s pendulum, he rigged up a swinging hammer that was guaranteed to knock the side of the coffin until he came back to stop it. This done he was out of the back door into the enveloping darkness, all within some quarter of an hour.

Mr. Hyde prowled round the house investigating. He then returned to the hall and looked round for a place to conceal himself, and having marked one, called for Mipps to bring him some drink. The hammering continued rhythmically, so he shouted louder – still no reply, but monotonous knocking, and he strode in bad temper whence it came. Seeing Mipps’s foxication working gaily infuriated him and he smashed it quiet – returning to the hall where he saw a bottle of brandy on a table by the fire. He took a generous pull, extinguished the lights save one, then slipped behind the heavy curtains into the bow of the window, where he had a good view of both inside and out.

He had not long to wait for he heard a door open and stealthy footsteps coming towards his hiding-place. His pistol at full cock, he was tense, ready. Suddenly the curtains were pulled aside, and what he saw made him utter an oath of satisfaction.

‘I have you covered,’ he said quickly. ‘The Scarecrow, by all that’s fortunate!’

The answer came back from behind that hideous mask. ‘The Revenue, by all that’s damnable.’

Mr. Hyde was in luck. ‘So this is your headquarters,’ he sneered. ‘My patience has been rewarded, Mr. Scarecrow. Only the Revenue Officer from Sandgate, he won’t give us much trouble, you thought. Just another dull-witted Preventive man to be hoodwinked. But now we’ll see who looks the fool. A local trial at Dymchurch you’ll be thinking – the jury packed with sympathizers you have bribed. Judges frightened or in favour – headed by that muddlehead the Squire, if Squire he be or muddlehead.’ He laughed unpleasantly. ‘Nothing so comfortable, Mr. Scarecrow, sir. I’m not taking any chances. A thousand guineas is a thousand guineas either way, alive or dead, so I’m going to shoot you out of hand.’ He forced the Scarecrow away from the window at the point of his gun and the black figure backed to the far corner of the refectory table.

‘Quite understandable, Mr. Hyde,’ the weird form croaked, ‘but you are wrong. This is much more comfortable than a crowded Court House. What more could one wish for in one’s last few moments – a pleasant fire, a bottle of wine, a good friend – so you will be living up to Holy Writ. Do unto others as ye would they should do unto you.’

‘Holy Writ, the parson – I suspected as much when I saw you riding better than the Squire.’ The Revenue Man was intoxicated with his cleverness, but one thing puzzled him. ‘How did you escape from your game of dice?’ The Scarecrow chuckled. ‘Well, no matter – you’ll not escape me. Sit down, Doctor Scarecrow. This is indeed a pleasant surprise. Take off your mask, Doctor Syn.’

The Scarecrow raised a long slim arm and swept off the mask with an elegant gesture – and the Revenue Man stared open-mouthed in dumb surprise.

Before him, dressed in those fantastic rags, high-booted, black-gloved – her lovely, laughing face with auburn hair tumbling about it, was Cicely Cobtree. She bowed mockingly: ‘At your service, Mr. Hyde,’ she said.

He exploded. ‘Great God, is this a jest?’

She laughed at his vehemence. ‘A very good one, Mr. Hyde, since it never entered your dull wits that the Scarecrow might be a woman.’

‘No, it hadn’t,’ he thought, ‘so that was it; well, she’ll get no change from me.’ ‘“The Parish Spinster”, eh?’ he sneered. ‘Devoting your life entirely to good works. God! what fools we’ve been.’

‘The cap and bells, Mr. Hyde?’ she suggested calmly.

He was now all white, cold anger at her studied flippancy.

‘You’ll jest with me no longer, Mistress Scarecrow – and do not think that being a woman will soften Nicholas Hyde. Do unto others, eh? I’ll tell you what I’m going to do with you. I’ll save you hanging with a bullet – then put back your mask and say “shot on sight” as any loyal citizen may do. Two minutes for a prayer, that’s all you’ll get from me. Unless you have a last request —”

Through the window behind him she saw the tiny flashing light from distant Double Dyke.

Involuntarily she shivered, not from fear of death but of failing him. She was numb now, trying to think what Syn would do in such a situation, but to excuse her shudder, not wishing him to think she was afraid – she told him she was cold and would like a drink.

His reply was typical. ‘Beggin’ for courage, eh? I thought you’d change your tune – you’ll have no help from me; get to your prayer.’ His whole manner gloated at her powerless femininity.

Over the Marsh, coming nearer and nearer until they seemed to be in the very room, came the long-drawn mournful warnings of the owl, as from Double Dyke the flashing became more urgent.

But now she had no need of drink nor prayer, for her own unspoken prayer had been answered, and she knew as clearly as if Syn had told her exactly what she had to do. Nonchalantly tilting back her chair, she threw up

her head in superb defiance. ‘I never begged from man – and I will not beg of God —’

Outraged at her cool insolence, when he had expected womanly pleading, he shouted almost in desperation: ‘Woman – go decently; sit up.’

‘I stand.’ Her voice rang out as her chair shot forward, and the tablecloth gripped between her feet slid along the polished table-top, bringing his pistol and the bottle with it to her hand. In an instant she was on her feet, covering him with his own weapon, while in the other she grasped the bottle and gave him a toast: ‘The Scarecrow’s health.’ Then throwing him the bottle she laughed: ‘Do unto others, eh, Mr. Hyde? Here’s courage, sir, until next time —’

Backing towards the door, eyes fierce in spite of her smile, she mocked. ‘That Parish Spinster rides to Aldington to light the Beacon for the run.’ Then out on to the bridge she dashed, calling wildly, ‘Gehenna! Gehenna!’ and flinging herself over the parapet almost before she heard the horse’s hooves, she found herself in the saddle, and spurred him up the rise on to the sea-wall road.

The Revenue Man remembered his other pistol in its holster round his waist and cursed his fingers for their fumbling. He wrenched it free and flinging to the window, broke a pane, and thrusting the muzzle through, he levelled it at the flying figure on the great black beast, silhouetted now against the rising moon. He fired: and fired again. His only answer was a mocking curlew cry; but as he watched his speeding target he saw just one spasmodic jerk which broke the rhythm of its flowing strides. Then, as though the Marsh had watched aghast this calculated deed, it took the heroic object out of sight in close embrace, to leave no trace but thudding fleeting sound. Silence. Then a strange, unearthly cry.

Chapter 23

The Shadow of Doctor Syn

The dice-box rattled. Doctor Syn lost again. The Dragoons, hilarious with drink and the sight of so many guineas piled before them, urged him to throw again. The guard-room was filled with smoke. Another all-butempty brandy-bottle stood on the table while from outside came the monotonous tread of the sentry, and from time to time his faint shadow passed the barred unshuttered window. The evening had been a pleasant one for the soldiers in their new billet, though when told but an hour ago that they were to guard a parson, they had cursed, thinking his presence would put a damper on proceedings; but here he was, a jovial companion who gave them drinks and had a dice-box of his own, and, though he did not seem to know very much about the game, paid up cheerfully in good spade guineas.

‘Come, Parson,’ cried the young officer, who was the worst of all in drink. ‘Your luck is bound to change. Try one more throw. Fill the glasses again, and we’ll drink to your success.’

‘That’s very civil of you, sir,’ said Doctor Syn. ‘’Tis good drink and warming. But I am distressed about that poor young man outside. He must be very cold. Could he not be permitted to come in and have a drink?’

The young officer, eager to seem important, by asserting his authority, gave permission, and the delighted sentry was hailed in. Glasses were filled, and the parson’s health was drunk. Then, as all were quite ready to relieve their prisoner of his remaining guineas, they pressed for the resuming of the game and the Vicar’s throw.

Doctor Syn agreed readily. ‘Faith, gentlemen, ’tis a good thing I found occasion to bring my dice with me. They have been the means of escaping many dull hours in the past, and I would be willing to lose twice this amount to such gay companions as yourselves to escape the tedium of confinement. But this is positively my last throw so I trust the dice will not fail. Dear me, ’tis hot in here, perhaps ’tis the excitement of the game.’ He took from his pocket a large silken handkerchief, and apologetically mopped his brow, holding in his other hand the ivory shaker. Then, seeming to be full of almost childish concern as to the results of his throw, he rose, and, with a charming smile, held the box high while turning away his face, hiding it in his handkerchief, making pretence that he dare not look. He shook. And shook again. The dice rattled. One long sensitive finger felt for the eye of the carved dragon. He threw. His wrist flicked round as his arm came down. The dice shot out and flashed unusually as they bounced from the force of the throw. Whether it was the effects of the wine or no the soldiers were never sure, but they could have sworn that at that very moment they saw a faint powdery mist arise from the table.

Suddenly they were overcome by a ghastly nausea. The room went dark before their eyes and a poisonous stench assailed their nostrils and gripped their throats. They retched violently. Their eyes ran. And through the haze of their vomiting they dimly heard the Parson say: ‘Dear me. Dear me. Too bad. Whatever is the matter? I must run and fetch Doctor Petter.’ Then they knew no more.

Cicely’s window was dark and he felt beneath it for the bundle. It was not there. Something had gone wrong. He knew that neither Cicely nor Mipps would fail him – yet something had gone wrong. Only one thing to do: return to the Vicarage. A cold fear clutched at his heart as he raced across the Glebe. He saw the flashes from Double Dyke as he ran, and heard the owl’s reiterated warning. ‘Where is the Scarecrow?’

Then out of the blackness of his shadowed house, into the rim of moonlight on the wall, leapt a great beast – Gehenna. His heart leapt with it. Gehenna – with a rider on his back – a slim, lithe figure clean cut against the sky.

Along that lofty ridge it sped like a black arrow, and apprehension thundered in his brain, in beat with the flying hooves.

Then with a noise of smashing glass a spurt of flame darted from his window. He heard the hiss of a bullet as it passed and the percussive thud of the report. And as he watched in agonized confusion another flame. It was the second shot. He saw his black horse quiver – then plunge on, the rider with it. Which had been hit? As if in answer to this unutterable possibility his whole spirit seemed to be torn from him in one wild cry:

The Revenue Man, his pistol still smoking in his hand, stood staring across the chequered patches in the moonlight as if he hoped to see that moving figure once again. Deep in his dull soul he knew his action had outstripped his reason, and that he was damned. The whole night turned accusingly against him and each inanimate thing cried ‘Murder’. No movement could he see to give him hope, only the Marsh menacing back.

Then, as if hypnotized he turned – and saw in the firelit room, a vast shadow filling it and striking terror to his very bones. It was as if the Marsh had gathered itself into one great spirit of revenge; and down the shaft of moonlight through the door came the living cause of his deadly fear. He backed and backed, in mesmerized, jerked movements, while slowly – towering towards him stalked Doctor Syn.

Then suddenly a red glow suffused the midnight sky, and the whole room came to life with flailing limbs and lightning stabs of pain. He knew no more.

A few deft strokes and Syn was gone, out into the night, rushing blindly towards that blood-red signal on the Knoll.

Cicely had felt Gehenna shiver under her but calmed him with her hand. She wanted to speak to him, to tell him not to fail them now, but no sound came, and she was only conscious of a numbing ache and a great longing to lie down and sleep. So she crouched in the saddle and her arms slipped about his neck. The reins were gone. But the animal charged on – giving her courage as if he knew his master’s life was on his back. Lifting his mighty head, his lips curled from his teeth in a defiant scream which told her of his intended spurt. It came like a thunderbolt, which hurled the ground behind them, as over the shining pathway of the broad dyke they met the rising ground. Then on, and up, and round the way he knew, right to the skies, the great horse carried her, stopping with hooves dug in and foaming head upon the very pinnacle of Aldington. She slid from the saddle, and the soft thick turf filled her once more with the desire to rest – but Gehenna pawed the ground and whinnied, and she dragged herself towards the beacon pile. With numb fingers she felt for the flasher in the Scarecrow’s pocket, and gathered all her strength for this one last effort. The straw caught, and crackled towards the tarred heart of the beacon, as the flames bit through and up as though to lick the stars. She stood swaying, warm now, and the great horse came behind and nosed her from the flying sparks. She could not mount again to ride away, but she knelt, and then lay down, and with Gehenna as her sentinel she slept, while he called out his trumpetings for help.

Heading the cavalcade towards the hills Mipps heard Gehenna’s call, and his far-seeing eyes, trained in the watery places of the world, saw the black shadow against the blazing fire, the saddle empty. The Scarecrow’s rule to all who fired the beacon was ‘Light and ride clear’. Tonight the Scarecrow was to light it himself. What then had happened? Had the dice-box failed? If so, who rode Gehenna? Mipps had not been able to find his master and warn him of the Revenue Man’s presence in the Vicarage, and had been forced to carry out his orders as arranged, with this unaccomplished self-appointed task knocking at his mind. So full of apprehension, Mipps spurred towards the beacon with Vulture and Eagle in his wake.

Every window facing the hills on Romney Marsh reflected the significant blaze. The run was on. The luggers could creep in to land their cargo. Behind a number of these same windows lurked excitement and activity. But behind one window on the wall all was still. The room was in darkness save for the warm light of the distant beacon, which embracing the chill, pale quality of the moon, gave to it an unearthly atmosphere. This mingled light shone on the figure of a man who was bound to the banisters of the staircase. His body was limp, his head sagged forward, he might have been alive or dead.

The room was deathly quiet. At last there came the sound of horses’ hooves – then footsteps crunched the shingle – then whispered conversation as cloaked figures appeared in the open doorway. Between them they carried the limp shadow of the Scarecrow and placed her gently on the settee, the cruel mask still hiding her face. Mipps spoke to the Nightriders beneath his breath.

‘’Ere’s a damnable night’s work,’ he said urgently. ‘A foul bullet through the back and no one we can trust to tend it. I hoped to find the Vicar here – you must ride and scour the Marsh and tell him wwe have desperate need of him. Ride like the lightnin’, and pray God you bring him ’ere in time.’

The Nightriders vanished; they understood – their leader, or so they thought, was in danger – and they rode as for their lives. Mipps was desperate. Where was his master? He knew what this would do to him, yet now he did not know what to do himself. He stood over the settle, and now they were alone, carefully, with his trembling hands, removed the incriminating mask so that she could breathe more easily. Even as he did so she spoke in hasty whisper. ‘Mr. Mipps – the Court House – why did you not send them there?’

But Mipps had already seen the figure of the Revenue Man lashed to the banisters with skilful knots.

‘Because I knows his work when I sees it,’ he said. ‘And I knows there ain’t four walls can hold him when he’s a mind to get out and because I knows that —’

‘Orders is orders, Mr. Mipps?’ she completed.

He nodded once, then sadly shook his head.

‘Oh, do not blame me for disobeying him,’ she pleaded. ‘’Twas the time

– I thought he could not do it in the time – and such a simple thing for me to do.’

Mipps told her there was no blame to her: she’d done a good night’s work and done it brave and Bristol fashion. She thanked him and a smile played round the corners of her mouth. ‘There is a penalty, is there not, for disobeying orders?’ she asked, then as a twinge of pain twisted the smile from her face she whispered: ‘And I must pay it —’

A voice from the shadows answered her. ‘Would that I could pay it for you —’ Mipps turned on the Revenue Man, who was stirring in his bonds, and lashed out like a fighting terrier.

‘Aye, so you should, you dog.’ This was the Mipps well known to Clegg; lucky for Mr. Hyde he did not act without his master’s orders. ‘So you should, you dog,’ he repeated, ‘as a reward for foul play.’

‘No, Mr. Mipps – not foul play.’ Cicely lifted herself and spoke in a firmer voice. ‘He shot on sight, as any loyal citizen may do.’ She turned to the Revenue Man, and though shocked to see him in his present plight, her mind could not take in what had happened. ‘I wish to thank you, Mr. Hyde,’ she said gently. ‘The Court House would have been so crowded. I am happy here. A pleasant fire; some wine.’ She turned to Mr. Mipps and asked him to fetch some wine and a glass for Mr. Hyde. Then seeing that so tightly bound, he could not drink, she ordered his immediate release. Mipps demurred, until she laughed: ‘Scarecrow’s orders, Mr. Mipps.’

He did as he was bid, realizing now that she must have her way in everything, and when she asked him to tidy the room lest the Vicar should be grieved to find it in such disorder, he obeyed, and found to his amazement that Hyde was helping him.

She watched them lift the heavy cloth and place it on the highly polished table; then as she saw the Revenue Man looking at her with an expression of desperate guilt on his face, she shook her head and said gently: ‘That is our secret, is it not?’

The Revenue Man did not know, himself. Never in his life had he felt like this before. He answered her with a newly found sincerity: ‘Whatever secrets I have learned tonight shall go no further. Your teaching shames me, Mistress Parson.’

She hardly heard him, for her wandering mind was out – searching the secret places of the Marsh, and a greater fear was upon her. ‘Oh, Mr. Mipps,’ she cried. ‘Why does he not come? ’Tis such a little time. I would that I had known him all your twenty years. Suppose he does not come.’ She was trembling now, with the desperate urgency to be near him. If that could not be, then she must somehow be enveloped by him; hear his name spoken; and so she begged Mr. Mipps to tell her some story of him, saying there must be one she had not heard. Mipps was silent: not because he did not remember one – for indeed the tablecloth had brought back to his mind a scene in Santiago, where Clegg had once again escaped to save his life. But he hesitated lest it should incriminate his master. Then as she urged him to be quick, he saw Hyde’s face and knew that they were safe from him. He held the glass of brandy to her lips, telling her that if she would but drink, he would begin. She obeyed him eagerly.

‘Well – I remember once – there was a time…’ Mipps spoke slowly and with great effort: ‘…he done a very nippy dodge: that was the time he saved…’ He could not go on, thinking of how he, himself, would now give anything to save her and his master from this calamity. Instead, he gulped, and the tears ran down his poor old nose. ‘Oh, Miss Cicely, Mrs. Cap’n – Miss —’

She looked at him and loved him, finding excuses to save his embarrassment. She hoped he had not caught Marsh ague, he was shaking so. She feared it was a cold, for indeed his eyes were running. His weakness gave her strength, and she fumbled for her kerchief, a tiny square which she handed to him, saying: ‘Come, give me the glass and do you take my handkerchief.’ She shivered: ‘Is it not cold? Mr. Hyde, come nearer to the fire and let us drink a toast.’

The Revenue Man hardly knew what he did or said, but he moved towards her and she heard him give a toast – a strange one, from his lips. ‘The Scarecrow.’

And then she saw behind him in the doorway what she had prayed to see just this once more, and her lips moved: ‘Christopher.’

As in a trance the wild-looking shell of Doctor Syn, dishevelled from his frantic searchings on the Marsh, moved like a shadow and was on his knees beside her. She took his trembling hands and with what little strength she had, tried to bring him back. ‘L’Épouvantail, at your service.’ It was a very gay whisper. She put her head on one side and smiled at him – a tiny, frowning smile. ‘Forgive such a clumsy rendering of the part. Perhaps, after all, I am – but just a petticoat. And I was wrong. The Scarecrow is a ghost. For he must always rise while Aldington stands high.’ As though to prove her words, the beacon flames leapt higher and the whole room lightened up and seemed ablaze. ‘You see,’ she said. ‘The Beacon is alight. I heard the curlew cry three times. I should have heeded Mr. Mipps, but thought you could not do it in the time. What could I do as Spinster but devote my life… All the King’s horses and Revenue Men…’

He was looking at her in dumb agony, and she, caressing and stroking his arm, looked down and was the memory of a dream. She slipped her had beneath his sleeve till her fingers rested on the branded mark. ‘Why, Doctor Syn,’ she whispered, ‘your sleeve. The button is still loose. It will only take a moment if you have a spool of black. I have forgotten my chatelaine.’

She raised herself and, leaning forward, kissed him lightly on his bowed head, so close that only he could hear her sighing words: ‘Dear, kind old Doctor Syn, I am so happy. My first good deed shall be…’ And she was gone.

And with her went the Beacon light, for at that moment it had flared up higher than before, to flicker swiftly out. The silent room was now quite dark, save for the arrow stabs of moonlight that shot in from the window, and the shining pathway through the door.

The husky voice of Mr. Hyde broke the silence. ‘I, too, was wrong. The Scarecrow is a ghost.’

He moved humbly and stood behind the stricken man. He also wanted help, and strange, this parson was the man to give it. He longed to take the Vicar’s hand. Instead, he turned and, passing Mipps, said quietly: ‘You know where you can find me. I shall be ready if he wants me.’

And then he crossed the bridge and went his way along the Dymchurch Wall.

Mipps made no attempt to hinder him. He knew the danger there had passed, and here at hand another must be reckoned with – his master’s reason. There might be one way to save him. If he could make him see that here was no lost love: rather, a gallant ending to a member of the Brotherhood.

With his hand on his master’s shoulder he looked down and said:

‘I pays my respects to Captain Clegg’s Lieutenant. God Bless her gallant spiriti. Come, Cap’n, we must carry her home.’

But she was home already.

Chapter 24

The Shadow of Clegg

Mr. Mipps was frightened. In fact, he was desperate. He had thought that his master might lose his reason and run wild. That he could have understood and dealt with as he had in the old days with the raving Clegg, which terrifying though it had been, was not in any way comparable with this new phase; for here was a Doctor Syn whom Mipps had never met before. Since the night he had carried Cicely to the Court House, he had not uttered one word. For three days he had not been seen to eat or drink, and he certainly had not slept, for Mipps had watched him pacing the library at night and striding the Marsh by day. Mipps had shadowed him, hardly letting him out of his sight lest he should end his misery by some violence. Here was no brandy-drinking demon, but rather a cold, calculating fiend; as though the man were fighting with his soul over some vital problem. Out of all this a conviction came to Mipps that he had reached the climax; for had he not put his affairs in order as if he were going away on some long journey? Mipps instinctively knew that this journey was not to foreign parts and the life they used to know.

The Sexton was not alone in his anxiety. The whole village shared it. They had been told that Miss Cicely had met with a riding accident. But there were certain things that mystified them. The sudden departure of Mr. Hyde, who for no apparent reason had stopped prowling, Doctor Syn’s neglect of parish work (he was not even at the funeral), his wild appearance, and his eternal vigil on the Marsh, never astride the fat white pony; the Squire’s absence in London; and above all the fact that the Scarecrow had issued no orders, so that the vast organization which meant to so many a living was at a standstill.

There was, however, one person who did understand, and who in all her wisdom was biding her time. Miss Gordon, though profoundly shocked, feeling that she was in a way responsible for that night of tragedy, determined to keep her promise of maintaining friendship. It was in this frame of mind and upon the fourth day at noon that she encountered Mr. Mipps, a sad little figure upon the sea-wall, looking through his telescope. She noticed, however, that it was not trained upon the shipping in the Fairway, but having his back to the sea he was sweeping the hillside across the Marsh. He was looking through it intently and did not notice her approach. She asked him if he had it focussed upon the old Roman harbour steps at Lympne. He turned sharply and looked at her in some surprise, for indeed he had had it fixed upon that very spot. She begged him to adjust it to her eye.

There in that circle of the telescope, framed like a miniature, was what she had been expecting. She turned to the worried little Sexton and together they evolved a plan. Returning to the Vicarage, she swept Mrs. Honeyballs out of the way, and prepared with her own hands a tasty meal. Mipps saddled the white pony with panniers into which the food and wine were packed, and within a quarter of an hour a quaint little party set off. Miss Agatha rode the Vicar’s pony, followed by Mr. Mipps on Lightning, his very aged donkey, while Mister Pitt, the poodle, frisked and trotted on ahead. Inside Miss Agatha’s vast reticule swinging upon her arm was a beautiful, bound, clasped book, whose small golden key reposed in the old lady’s purse.

‘And so, Mr. Mipps,’ she had said, ‘if he can eat the meal, drink the wine and read this book, he’s cured.’

* * * * *

Two hours later Mr. Mipps was again looking through his telescope upon the sea-wall. This time he was watching for a signal. At last it came; bright flashes that caught the glass and made him blink. But Mipps did not care. On the contrary – he threw his three-cornered hat into the air and executed there and then his famous hornpipe.

* * * * *

Miss Agatha was sitting in the sunshine, her plaid spread out upon the Roman pavement. She held in her hand a very small mirror and with the help of this was arranging a naughty wind-blown curl, though for quite a long time after it was arranged satisfactorily she continued to flash her mirror in the sun, making it dance here, there, and everywhere. Indeed, once she inadvertently caught the Vicar full in the face. He looked up from his book and smiled, but returned to it again while she repacked the baskets. There was very little left.

Some life had returned to Doctor Syn’s face. The full French wine too had done him good, but the book upon his knees, as Aunt Agatha had predicted, was his real salvation.

He turned the pages and his face reflected what he read. At times gay – then sad – amused and tender. And, indeed, there were times when the tears fell unashamedly on to those carefully written pages.

He went back to the beginning of this endearing volume and re-read the title. Round childish handwriting.

‘Cicely Cobtree – her Book. Given to me by my Great Aunt Agatha upon my fifteenth birthday, November 25, 1775. I shall keep it for my journal. Very special thoughts and happenings.’

Strange that today was another 25th of November, her birthday and that the first ‘happening’ should be of him. He read: ‘My dear Papa’s best friend, Christopher Syn, has returned from the Americas. I wish he had come home before. He tells exciting stories.’ Then further on: ‘Doctor Syn is now our Vicar here. I like Church now. Though I had always imagined for myself a tall fair gentleman. I know now I was wrong. I like his eyes best. Oh yes – and his voice. I am sure Charlotte is in love with him. I wish I was her age, and had fair hair.’ Another page: ‘A lovely day. I talked to Mr. Mipps. He’s back from Sea, and he’s going to be Sexton.’ Over again: ‘Sister Maria the Silly had a nightmare about the Scarecrow. He is supposed to be a Ghost in these parts, though Papa says not to be frightened; he is only a smuggler. I think he sounds exciting – but I still like Doctor Syn best.’ More leaves turned and now the Vicar’s face was grave. ‘Dear Sister Charlotte was buried today. They say it was a hunting accident, but I know different. I have not told anyone but I think it had something to do with Doctor Syn and the Scarecrow – I dreamt that she died for the Scarecrow. I wish I could have done it – but I would rather die for Doctor Syn.’