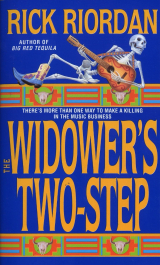

Текст книги "The Widower's Two-Step"

Автор книги: Rick Riordan

Жанры:

Разное

,сообщить о нарушении

Текущая страница: 9 (всего у книги 23 страниц)

19

I called my information broker from the pay phone at the Whole Foods Market complex on North Lamar. One of Kelly Arguello's housemates, I think it was Georgia, answered the phone, a little breathless like she'd been doing her morning aerobics. When I asked for Kelly she said, "I'm not sure if she's in. Who is this? "

I told her.

"Oh." Her voice went up half an octave. "Kelly's in. Hang on."

The phone smashed against something.

I heard Kelly laughing a long time before she got the receiver. She was telling Georgia to shut up.

Clunk. "Tres?"

"Kelly. How's school?"

She made a German ch sound in the back of her throat. "Midterms. Contractual law.

Any more questions?"

"I've got a missing person to track, need some paperwork collected on him. If you're too busy—"

"Did I say that? Are you in town?"

I hesitated. "Yes."

"Come over. I think I've still got a Shiner Bock in the fridge."

I stared at the roof of the parking garage at the other end of the lot. It was lined with giant papiermache groceries—strawberry, eggplant, milk. I said, "I could just Email the information if you need to study or something."

"You know better than that."

After Kelly hung up I stood there, glaring up at the huge papiermache chicken. Any resemblance to persons real or fictional was purely coincidental.

When I was first starting my apprenticeship Erainya had two words to tell me about finding an information broker: law students. They're happy to see even small amounts of cash and they don't ask questions except occasionally "Where's the beer?" They're used to working like dogs, they're bright, and they know how to get the best results out of bureaucracies. All that is a lot more than you can say for most of the people who run information services.

Unfortunately my law student helper had turned out to be a little more than I bargained for. Considering the person who referred her to me was her Uncle Ralph, I don't know why I was surprised.

When I got to Kelly Arguello's house in the neighbourhood of Clarksville she was in front clipping back a huge mass of honeysuckle that was taking over her exterior bedroom wall and threatening to grow into her window.

Kelly's not hard to spot. She's a girl who'd catch your eye anyway, but since she's moved to Austin and put purple highlights in her hair it's doubly easy.

"I love this stuff," she said when I came up behind her. "Unfortunately, so do the bees."

"You're allergic?"

Without looking away from her work she widened her eyes and nodded several times.

"The little guys buzzed in my window all summer long. This is the first morning it's been cool enough to do some pruning. If we keep this place for the spring semester I'm going to have to trade rooms with Dee."

She got her weight balanced on the ladder, then reached a little farther across the window. She was wearing a surgeon's green scrub shirt and men's white swim trunks that should've done a good job hiding her figure but somehow didn't. She still showed off the lean, smoothly sculpted body of a teenaged swimmer. She was twenty one, barely, but no bartender in his right mind would've failed to card her. Her purple and black hair was pulled into a ponytail that swung back and forth every time she clipped.

"You're going to fall," I said.

"Well, hold the ladder, stupid."

I held the ladder, looking sideways so my face wasn't in Kelly's swim trunks. I concentrated on the house next door.

"Your neighbours are gardeners, too."

Kelly made a "sshhh" sound, though nobody could've heard me. The nextdoor neighbour’s front yard consisted of dirt, ragweed, an old Chevy chassis set on cinder blocks, and a brown Frigidaire leaning against an oak tree.

"I've got this idea." Kelly stuck out the tip of her tongue as she tried to clip a vine. "Me and Georgia and Dee are thinking about quitting law school and going into the yard appliance business. You know—selling old washing machines and refrigerators that people can set in their front yards. You drive around this side of Austin you'll see there's obviously a big demand for them. What do you think?"

"I think your uncle would be proud of you."

She smiled. There aren't many times I see the likeness between Kelly Arguello and her uncle. I see it when she smiles. Though, on Kelly, thank God, the smile doesn't have the same maniacal edge.

She leaned out for one last curl of honeysuckle that hung over the window. "Okay.

Enough for now. There's a cooler on the porch. Get that Shiner Bock."

"It's tenthirty."

"You want a light beer instead?"

I took the Shiner. Kelly drank a Pecan Street Ale. We sat on her wooden porch swing while she booted up a little blue portable computer, then started copying the information I had so far on Les SaintPierre.

The laptop beeped unpleasantly. She cursed, held it aloft by the screen, resettled herself so her bare feet were pulled up under her, then put the computer back in her lap and hit the delete key several times.

"New toy?" I asked.

She wrinkled her nose, rabbit style, and kept it that way for a few seconds.

"Ralph?"

She nodded. "I told him I was saving up for one. Next thing I know he's bought it for me. He's always doing that."

"He's just upset you got all those scholarships. Had his heart set on paying your way through college."

"Probably he'd beat up my professors if they didn't give me straight A's."

"That's not true," I insisted. "He'd pay to have them beat up."

She didn't look amused. She kept typing, squinting as she tried to read Milo Chavez's handwriting.

"Lo hace porque le importas, Kelly."

She acted like she hadn't heard me.

"You want all the paperwork on this guy?" she asked. "Like last time?"

"Get his marriage certificate. DMV. Credit. He's also got an air force record. We can at least get his date and nature of discharge on that. Check the tax rolls, especially deeds, building permits—"

"Basically everything," she summed up. She flipped through some more papers, gaining confidence in the task until she hit the personnel files from Julie Kearnes'

computer, all seven pages worth. "Whoa."

She scanned a few lines, looked up at me wideeyed. "What the hell?"

"Part of our problem. This guy might be a vanisher."

She nodded slowly, trying to decide whether she should pretend she was following me or not. "Yeah?"

"Let's say you were into something dangerous."

"Like what?"

"I don't know. But you know you're going to be making some enemies and you want to leave yourself an escape hatch. Or maybe you're just unhappy with your life anyway and you've been planning to skip for a long time, then something bad comes up and you figure the time is ripe. Either way, you want to disappear off the face of the earth for a while, maybe forever. What would you do?"

Kelly thought about it. It can take law students a while to turn their training around—to look at the illegalities that are possible rather than the legalities. When they finally start thinking in reverse, though, it's scary.

"I'd start constructing a new identity," she decided. "New ID, new credit, completely clean paper trail. Maybe I'd butter up somebody who had access to employee files for some big corporations, like these."

She scanned the printouts more closely. "I'd look for somebody deceased who was about my age, somebody who died far away from their town of birth so their birth and death paperwork would've never met up. I could order their birth certificate from their home county, get a new social security number with that, then a driver's license, even a passport. That about right?"

I nodded. "A plus."

"People really do this?"

"A couple of hundred times a year. Hard to get figures because nobody ever advertises success."

"Which means—" She started to recalculate the job I was asking her to do. "Holy shit."

"It means we have to narrow the field. We have to find the most likely candidates from those files who might make viable new Les SaintPierres—males in their late forties who were born out of state and died fairly recently. There shouldn't be too many. Then we have to find out if any of those dead folks have requested new ID paperwork in the last, say, three months."

"That could still mean five or six names to track. And even then we might miss him. If he really did disappear."

"That's true."

"How long do we have?"

"Until next Friday."

She stared at me. "That's impossible. I'll have to get down to Vital Statistics today."

"Can you do it?"

She raised her eyebrows. "Sure. I can do anything. But it's going to cost you."

"How much?"

"How about dinner?"

I plinked the rim of my beer bottle. "Kelly, your uncle owns a very large collection of guns."

"What—I can't ask you to dinner?"

"Sure. I just can't accept."

She rolled her eyes. "That's such bullshit, Tres."

I stayed quiet and drank my beer. Kelly stuffed the personnel files back into the folder and returned to typing. Every once in a while the fragrance of clipped honeysuckle would drift across the porch, a strange smell for midOctober.

I pulled five of Milo's bills from my backpack and handed them to Kelly. "You run into any unusual expenses, let me know." "Sure."

She dug back into the folder and pulled out Les Saint Pierre's photograph. "Yuck."

She tried to shape her expression like Les'. She couldn't quite get the eyebrows right.

Across the street a businessman stumbled out his front door and spilled coffee on his tie. He lifted both arms in a Dracula pose and swore, then walked more carefully toward his BMW. His duplex looked like it had been built in the last twelve hours—all white aluminium siding and the lawn still made up of little green squares that hadn't grown together. The house next to his was an old red shack with a store on the side that sold ceramics and crystals. Austin.

"What was it like growing up without your mother?" I asked.

Kelly lifted one eyebrow, then looked at me without turning her head. "What makes you ask that?"

"No reason. Just curious."

She stuck out her lower lip so she could blow away the strand of grapecoloured hair that was hanging in her face. "I don't think about it much, Tres. It's not like I spent my childhood thinking I was different or anything. Dad was always around; five or six uncles in the house. Things were just the way they were."

I swirled the last ounce of beer in my bottle. "You remember her at all?"

Kelly's fingers flattened on the keyboard. She stared at her doorway and, momentarily, looked older than she was. "You know the problem with that, Tres? Your relatives are always telling you things. They remind you of things you did, the way your mom was.

You mix that with the old photos and pretty soon you've convinced yourself you have these memories. Then if you want to stay sane you bury them."

"Why?"

" Because it's not enough. You grow up with men, you have to learn to deal with men.

The fact you don't have a mom—" She hesitated, her eyes still searching for some

thing in the doorway. "With a mom, I guess you get some intuition, some understanding and talking. With a bunch of guys in the house, little girl has to take a different tack. Learn sneaky ways to get them to do what you want. Good training for working in law firms, actually. Or working for you."

"Thanks a lot."

Kelly smiled. She looked through the other documents in my packet, found little that would help her, then resealed the manila envelope. She closed the laptop.

"I'll call you as soon as I get something," she told me. "You're heading back to S.A.?"

I nodded. "You want me to tell your uncle anything?"

Kelly stood up so quickly the porch swing started moving cockeyed. She opened the screen door. "Sure. Tell him I'm expecting a dinner out of you."

"You want to get me killed."

She smiled like I'd guessed the exact thing she had in mind, then shut the door behind her and left me alone on the porch, the swing still zigzagging around.

20

There are two staterun rest stops between Austin and San Antonio, leftovers from simpler times before developers plopped convenience stores and outlet malls at hundredyard intervals all the way down the highway.

I resisted the urge to pull into the first, even though Kelly Arguello's Shiner Bock was working its way through my system, but by the time I'd passed through New Braunfels my bladder was twisting itself into funny little balloon animals. I decided to exit at the second rest stop.

I made such haste parking the VW and shuffling up the steps toward the john that I didn't take much notice of the pickup and horse trailer I'd parked behind.

Nor did I take much notice of the guy next to me at the urinal. He smelled faintly of cigarette smoke and the checkered shirt and the profile of his face looked familiar, but there is no space quite so inviolable as the space between two men at the pee trough.

I didn't look at him until we'd both suited up and were washing our hands.

"Brent, right?"

He clamped his hands on the paper towel a few times, frowning at me. He hadn't changed clothes since yesterday, nor shaved. The bags under his eyes were puffy, like the extra tequila from last night's gig had drained into them.

"Tres Navarre," I said. "We met last night at the Cactus, sort of."

Brent threw away his towel. "Cam Compton's forehead." "Right."

"I remember."

Brent looked past me, out the entrance of the john. I was standing between him and the exit, which made it difficult for Brent to get around me. He obviously wanted to.

Two men having a conversation in the bathroom was only slightly less awkward than acknowledging each other at the urinal. Maybe I should compensate by offering him some Red Man. Mention the playoffs. Bubba etiquette.

"You with Miranda?" I asked.

He looked around, uncomfortably. "No. Just the equipment." "Ah."

He shuffled a little more. I took mercy and stepped aside so we could both walk out at the same time.

The rest stop was doing a pretty good business for a weekday. Down on one end of the grassy oval island the picnic benches were overflowing with a huge Latino family.

Fat men in tank tops drank beer while the women and children streamed back and forth between the tables and their battered station wagons, bringing ice chests and boxes of potato chips and marshmallows. A little dog was doing circles around the kids' legs. The far curb of the turnout lane was lined with semis, the cabs dark and the drivers inside sleeping or shaving or eating, staring at the horizon and thinking whatever it is truckers think.

A local Baptist church had set up an outreach table at the bottom of the bathroom steps. Several perky blondhaired women offered DUI fliers and free pocket Bibles and donuts and coffee. A green poster board sign announcing CHRIST LOVES TRAVELERS, TOO flapped in the humid wind.

Brent Daniels wasn't thrilled when he realized we had parked next to each other—my VW right behind his pickup and trailer.

Brent's rig was a white Ford with brown stripes. The windows were tinted almost pure silver, making it impossible to see inside the cab. The trailer was a onehorse job, brown metal, with the words ROCKING U RANCH thinly painted over in a beigebrown that didn't match the rest of the metal.

"Equipment in a horse trailer," I said. "Inventive."

Brent nodded. "Cheaper than a van. Willis got a good deal on it."

We stood there. I wasn't quite sure why Brent was staying to talk. Then I realized that for some reason he wanted me to leave first.

When you've got an advantage, I say press it.

"I was talking to Miranda about your music this morning. She said you wrote most of the songs. Said you were real supportive about her recording them."

Brent hooked his fingers on the door handle of the Ford and hung them there. His expression was hard to read, mostly gruff apathy with maybe a little dry amusement around the edges. With the facial stubble a day thicker I could see that some of the whiskers were coming up white, like his dad's.

"Supportive," he repeated. "That a fact?"

"She seems to think so. You ever try to record on your own? Make it in Nashville?

You've got some nice songs."

That brought the amusement a little closer to the surface. A tic started going in Brent's left eye, like he was trying to smile but was having a shortcircuit problem.

"Ask Les about that," he said. "I'm fortytwo, didn't even start writing—" He caught himself, decided to change tack. "I didn't start writing until about two years ago. Most artists making it—fifteen to eighteen, some even younger. Miranda's barely okay at twentyfive. Les says you're over thirty as an artist, you're pretty much dogmeat."

"Les said that, huh? What is Les—fortyfive?"

Brent ticked his eye a little more. "Guess the rule don't apply to agents."

We both looked out at the highway as another semi roared by at planeengine volume.

Some raindrops were splattering the asphalt noncommittally, once every few seconds.

The wind was slow, heavy, and hot, and the clouds couldn't seem to decide what to do—break up or move in. They made the low hills an even darker green, almost purple.

"How about the rest of the band?" I asked. "Mr. Sheckly seems to think you folks'll be left out in the cold if Miranda's record deal goes through. Anybody besides Cam upset about that?"

Brent lost whatever smile he might've been starting to accumulate. He scuffed his boot on the curb, a small sign of impatience. "Suppose you'd have to ask them, wouldn't you? Julie's dead. Cam's fired. Pretty much leaves Ben French and the family, don't it?"

Behind us a trucker was flirting with one of the Baptist women, calling her Sweet Thing.

She was trying to keep her polyethylene smile in place, talking about how Jesus wanted the trucker to have some coffee and stay awake out there on the road. Her tone wasn't very convincing.

"You got a day job?" I asked Brent.

"Nope. How about you?"

Ah. A hint.

Brent kept his fingers hooked on the door, making no move to open it. I looked at the silvered window of the cab and saw nothing but me, bubbly and smeared in the glass.

"I didn't know better," I told Brent, "I'd think you didn't want to open that door."

Brent looked at his boot, then sideways at the Latino mutt dog, which was now doing tight orbits around the metal poles of the breezeway.

Brent smiled at the little dog.

"You working for Milo?" Brent asked me.

"That's right."

Brent nodded. "You best get at it, then."

He opened the door of the cab and got in, trying not to be too quick about it. I tried not to be too obvious about looking, but there wasn't much to see—just a woman's tan feet crossed at the ankles, propped up on the window in the miniature backseat like she was sleeping back there. She had painted toenails and a little gold ankle chain.

Brent closed the door and was lost behind the window tinting.

The truck pulled out and a big plop of warm rain landed squarely on my nose.

The Baptist lady breathed a sigh of relief because the flirtatious trucker had just left.

She called over to me and offered me a donut. I told her thanks but Jesus would have to find somebody else. All she had left were the jellyfilled variety.

21

"It's registered," Ralph Arguello told me. He slid into the backseat of his maroon Lincoln with me, then returned the Montgomery Ward .22. Chico pulled the car out of the pawnshop parking lot and headed south on Bandera.

"You were in there all of five minutes," I said.

"Yeah. Sorry so long. My friend at the data entry office, she does all the firearm slips for the pawnshop detail. Sometimes I don't want to wait, she'll do a pre screening for me, you know? Today she was a little busy." .

"You get the owner's name and address?"

"What do you think?"

"I think you probably got his grandmother's maiden name and his favourite flavour ice cream."

Ralph grinned. "Que padre, vato."

When Ralph grins he gives the Cheshire cat a bad name. He makes psychopaths nervous. Maybe it's because you can't really see his eyes, the way they float behind the inchthick round lenses. Or maybe it's the red colour his face turns, same as one of those chubby diablo masks they sell in Piedras Negras. When Ralph grins it could mean he's made an easy thousand dollars or he's had a good meal or he's just shot somebody who was annoying him. It's hard to tell.

He handed me a piece of paper from the front pocket of his white linen guayabera. In Ralph's meticulous, tiny block print it said: C. COMPTON 1260 PERRINBEITEL SA TX 78217.

"I got a story about this guy," Ralph offered.

That was no surprise. It was a rare and boring San Antonian Ralph Arguello didn't have a story about.

I read the name C. Compton again.

"Tell me your story."

Ralph produced a joint and started carefully pinching the ends. "Your man Compton works for that kicker palace, the Indian Paintbrush. You know the place?"

"I know it."

"You remember Robbie Guerra—halfback from Heights?"

I had no idea, as usual, where Ralph was going, or where his information had come from, but I nodded. "How is Robbie?"

"He's dead, man, but that's another story. Six months ago we had this nice deal going with a restaurant supply company and some of the places they delivered to. The Indian Paintbrush was one. Every tenth crate set aside, Robbie and me'd pick it up, everybody involved gets a little cut. Compton was some musician or something, but he worked day shifts with the business manager, too, some guy—"

"Alex Blanceagle. Freckles. Big ears."

"—that's right. Anyway, Compton and Blanceagle knew about our deal with the crates, they got their share, everything was suave. Then one night Robbie and me accidentally skimmed from the wrong shipment, okay? It happens sometimes. We came by on the guard's Coke break, like normal, everything looked cool, we started taking these big brown cardboard cylinders off the loading dock. We thought maybe they were full of copper piping or something because they were heavier than shit but we figured hell, goods are goods. Five seconds later we had all these gabachos with guns in our faces—Blanceagle and Compton and two German guys screaming in Kraut. Robbie and me got a talkingto, half of it in Kraut, with guns at our heads the whole time. Blanceagle was all yelling like he never saw us before and telling us we were lucky to walk away alive. So we said chupa me. That was the end of one restaurant supply deal."

Ralph lit the mota and took a long drag. He might've just been telling me about his last birthday party for all the agitation he showed.

"Describe these Germans."

Ralph gave a pretty accurate description of Jean, the man with the Beretta from Sheckly's studio. He described another guy who didn't sound familiar.

"What was in the cylinders?"

Ralph blew smoke. "No se, vato. All those rednecks and Nazis pointing guns at my ass I wasn't going to ask for no peeks. Probably KKK training kits, right?"

We drove in silence down Bandera for a few miles, under the Loop, into a residential area where the houses looked like army bunkers, flat and sunken behind old brick privacy walls and overgrown pampas bushes. There was some fresh gang graffiti on the walls. A phone booth on the corner of Callahan had been pried out of the ground and laid flat across a bus bench. On top of it was a line of empty MD 20/20 bottles that a little shirtless boy was hitting with a stick.

The sky wasn't helping the general impression that this whole neighbourhood had recently been stepped on. A layer of gray clouds was pressing down low, like insu

lation material. The air had heated up again, and now it was just hanging there, stagnant and heavy.

After a few blocks Chico leaned his head back and asked Ralph in Spanish if he wanted to stop by Number Fourteen, since we were passing by. Ralph checked his gold Rolex and said sure. Then he got Mr. Subtle out from under the driver's seat and loaded it. Mr. Subtle is his .357 Magnum.

"The homeboys been making noise," he said. "Pinche kids."

"Number Fourteen," I said. "Catchy name."

"Hey, man, you get over twenty pawnshops, you try naming them all."

He stuck Mr. Subtle in his jeans, underneath the guayabera. Most people couldn't wear a Magnum like that and look inconspicuous. Most people don't have Ralph's girth and his XXL linen shirts.

Chico found a Def Lepard song on the radio and turned it up. Probably still on the Top Ten in San Antonio.

"So," Ralph said, "you see my niece when you were up in Austin?"

"She's doing fine. Good worker, just like you said."

Ralph ticked. "She's going through this con crema phase, man. I don't get her sometimes."

"Con crema?"

"You know what I mean. She won't speak Spanish. Only dates white guys."

"No kidding."

Ralph nodded, shifting a little in his seat. I shifted in my seat. We stared out the windows. He decided to change the subject.

"Speaking of con crema, man, you hanging out again with that cabron, Chavez?"

I hadn't told Ralph anything about the case. Not that that mattered. Ralph had probably found out about my meeting with Chavez the day it happened. Anything that went on within the city limits, Ralph usually knew about it in time to start placing bets.

"Milo's tangled into something, Ralphas. I told him I'd try to help out."

"Yeah." Ralph grinned. "Pinche bastard ever figure out what he wants to be when he grows up?"

I had never been quite sure when or how Milo and Ralph had met. They'd simply always known and disliked each other. All three of us had gone to Alamo Heights, of course, but as far as I knew the two men had never exchanged a word, never acknowledged each other. I'd never been in a room with both of them at the same time. Aside from being North Side Latinos, the two could not have been further apart.

Ralph had come from poverty, from a factory shantytown where his father had died of cement dust in his lungs and secondgeneration natives still kept fake green cards because it was easier than making La Migra believe their nationality. Ralph had made it through high school on the strength of his football playing and cunning and a straightedged razor and the certain unwavering knowledge that someday he would be worth a million dollars. Milo had come from a placid, welloff family. He was one of the few Latinos who had been accepted in the white circles, been invited to Cotillion dances, even had a white girlfriend. The news that he'd toyed with music after high school, then business, then finally persevered through a law degree caused no surprise among his old friends, no excitement. No feeling that he'd tackled insurmountable odds. The fact that he'd changed jobs again, gone into the country music industry, would generate, at best, a few amused smiles.

"Milo's doing all right."

Ralph laughed. "Isn't he the one almost got you killed out in San Francisco?"

"That's one interpretation."

"Yeah. You remember that shit we used to drop in water in chemistry class? What was that—"

"Potassium."

"That's it. Boom, right? That shit is you and Chavez, man. I can't believe you're talking to that pinche bastard again. You thought about that offer I made you earlier?"

"I wouldn't be into it, Ralphas. I got enough worries."

Ralph blew a line of marijuana smoke against the window. He shook his head.

"I don't get you. I been trying since high school and I still don't. You push a guy off a smokestack ten stories up"

"Special circumstances. He was going to kill me."

"You break some pendejo's leg just because an old lady asked you to, for no money."

"He was ripping off her social security checks, Ralphas."

"Now you work for Chavez when you know he's going to fuck you up, man. Then I offer you five hundred a week easy, doing the same kind of shit, and you tell me you're not into it. Loco."

Chico had been quiet so far. Now he turned his head slightly and said, "Fuck him."

I looked at Ralph.

Ralph took another toke. "Chico's new."

"I got that."

Chico kept his eyes on the road, left hand on the wheel, and huge right arm draped along the top of the bench seat. He had LA RAZA tattooed in very small letters on his deltoid. His hair was covered with a yellow bandanna, tied in back, piratestyle.

"Fuck him," he said again. "What you need his pansy ass for, man?"

Ralph smiled at me. "Eh, Chico, this guy's okay. I saved his ass from some shitkickers in high school."

"You saved me?"

"Yeah, man. You remember." Then to Chico: "Changed his life, man. Became this martial arts badass. He's good."

Chico grunted, unimpressed. "Guy I knew in the pen did tae kwon do. Kicked the shit out of him."

We kept driving.

Pawnshop Number Fourteen was in a fiveunit strip mall just off Hillcrest, sandwiched between the Mayan Taco King and Joleen's Beauty Shop. Number Fourteen's bright yellow marquee said WE BUY GOLD!!!! The windows were painted with pumpkins and witches and smiling cartoon dollar signs that didn't quite go with the burglar bars and the shotgun displays aside.

A gallery ran in front of the mall, covered by a metal awning held up by square white posts. Leaning against the posts outside Number Fourteen were two young Latino guys, maybe seventeen, both in black jeans and Raiders jackets. They would've made good fullbacks if they'd been in school. Sitting on the sidewalk between them, leaning back on his elbows, was a much skinnier kid who'd evidently done his clothes shopping with the fullbacks. On all of them the clothes were huge and baggy, but especially on the skinny guy. The three of them looked like a family of elephants who'd gotten a group rate on liposuction.

Ralph and Chico walked up to them. I followed.

None of the kids moved, but the skinny one in the middle smiled. He had the pointiest chin I'd ever seen, with a little spiky tuft of adolescent beard at the tip. It made the lower half of his face look like it had been fashioned out of a stirrup.

"Boss man," he said. "?Que pasa?'

Ralph smiled back. "Vega. You want to take your Chiquita’s here and play somewhere else? You're cramping my business, man."

I got the feeling Ralph and Vega had gone through this a couple of times before. They looked at each other, both smiling, waiting for something to break.

What broke was our new man Chico's patience. He detached himself from Ralph's side and said, "Fuck this."