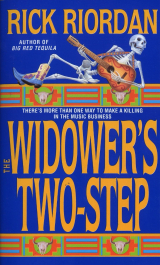

Текст книги "The Widower's Two-Step"

Автор книги: Rick Riordan

Жанры:

Разное

,сообщить о нарушении

Текущая страница: 8 (всего у книги 23 страниц)

17

"Mr. Navarro, isn't it?"

Miranda's dad shook my hand with both of his ^r and most of the rest of his body. This was a good trick, considering that to do it he had to put his walking stick in the crook of his arm and lean on his good leg and still keep from falling over.

"Navarre," I said. "But call me Tres."

Willis Daniels kept shaking my hand. His face was bright red, beaming like he'd just run the Iron Man triathlon and loved every minute of it.

"Course. Navarre. I'm sorry."

"No problem," I said. "San Antonio. Navarro. Historical connection. I get that all the time."

We were standing in the doorway of Silo Studio on Red River near Seventh. The studio was a singlestory refurbished warehouse with metalframed windows and brown stucco outer walls the texture of shredded wheat. The main door was at the rear of the building, where the parking lot was.

We were standing right in the doorway, me on my way in and Mr. Daniels on his way out and the guy with a dollyful of electrical equipment waiting two feet behind Daniels shit out of luck. Daniels didn't seem to notice him.

The old man squinted and leaned his face into mine, like a preacher about to offer me important words of comfort as I filed out of church. He smelled like wet leather and Pert.

"I apologize for last night," he said. "Hard situation, Cam getting out of control like that.

I surely didn't mean to misjudge you."

"Don't mention it."

"Cam was fired, of course."

I nodded amiably.

The guy with the dolly cleared his throat loudly. Daniels kept beaming at me.

With the solid red flannel shirt and black jeans and the curly gray hair now minus straw hat, Daniels looked even more like Santa Claus than he had the night before. He was mighty perky for somebody over sixty who'd played music until two that morning.

"You know you do look Hispanic," he decided. "I suppose that's why I thought Navarro.

It's the dark hair. Bit of a swarthy complexion. You don't mind me saying so?"

I shook my head. Swarthy. Maybe I should have kept the parrot. Gotten myself a cutlass.

"I hear you might be coming to our party tomorrow night," he continued. "I surely hope you can make it."

"Do my best."

"Fine."

We nodded at each other, both smiling.

I pointed to the parking lot, the way he'd been heading. "You're not helping with the recording today?"

He looked surprised, then chuckled and let out a whole string of little no's. "Just dropping off Miranda. Old man like me couldn't keep up."

He said his goodbyes with more handshaking and smiling and then finally noticed the guy with the dolly. Daniels made a big deal about getting out of his way and telling him to have a good day.

I watched Daniels drive off in a little red Ford sedan. The guy with the dolly disappeared around the corner of the building.

I crouched down and looked at the cement steps at my feet. Nothing. I looked up at the sides of the walls. The bullet hole was a puttycoloured gouge in the brown stucco, about four feet up, just inside the doorway. My index finger fit up to the first joint. The rim of the hole was scarred where the police had removed the slug but I could still get the basic trajectory. I looked south and up. Parking garage next door. Probably the third floor. Probably a .22—a stupid shot from so far away, more effective at scaring than killing, unless you got lucky. The police might've been up there looking for casings. Still . . .

I took a fiveminute excursion next door. I had a nice talk with a parking attendant about garbage collection days, then went up to the third floor and found what I wanted on the first try, right by the elevator. I put my prize in my backpack and walked back to Silo.

The studio's lobby was a remodelled loading dock. There was one door on the far wall marked PRIVATE and a sickly ficus tree in the corner that apparently doubled as an ashtray.

Next to the ficus tree, an Anglo guy in a sleeveless Hole Tshirt and Op shorts was leaning against the wall, reading Nashville Today. His head bobbed up and down like he was listening to a Walkman.

"Help you?" he asked.

"Gold records."

He looked up with just his eyes, his face still bent over the magazine. "What?"

"There's supposed to be gold records on the walls."

He scratched his nose, then made a small sideways nod to the door marked PRIVATE, the only other exit from the room. "Studio's that way."

"Thanks. I might've gotten lost."

His obligations to building security fulfilled, he went back to his magazine and his invisible Walkman.

I walked down a long hallway with several cheaply panelled doors on either side. Each had an identical PRIVATE sign. Someone must've gotten them on sale.

The hallway ended in a black curtain so thick it could've been sewn together from flack jackets. I squeezed around the edge into a large circular room where I could hear Miranda singing but at first couldn't see her.

The place smelled like burnt Styrofoam. Ducttaped cords ran along the floor, overhead among the fluorescent lights, up the walls that were apparently constructed from egg carton material.

Spaced here and there around the recording area were gray portable partitions, poofy and overstuffed so they looked more like vertical pillows than walls.

In the centre of a V made by two of these was Miranda Daniels. She wore huge black headphones that doubled the size of her head. One large boxy mike was pointed toward her face and another angled down toward her guitar, and with all the wires and cords and the people looking at her from the glassedin control room I couldn't shake the impression that I was watching some kind of execution.

I skirted the room and walked up five steps into the control area, where Milo Chavez and three other guys were standing at a recording console that looked suspiciously like a Star Trek energizer.

Miranda was midsong—one of the faster numbers I'd heard the night before. The sound was crisp and clear from the two shoeboxsize wall speakers, but it seemed thin with just Miranda's voice and the guitar. The studio acoustics seemed to suck all the excess sound out of her voice so the words just evaporated as soon as they left her mouth.

Milo glanced at me briefly, mumbled a greeting, then continued glaring through the Plexiglas.

One of the engineers was hunched so low over the console I thought at first he was asleep. His head was cocked sideways, his ear only an inch from the knobs like he wanted to hear the sound they made when he turned them. The other engineer was keeping a close eye on the computer monitor. More accurately, he was keeping a close finger on it, tapping the little coloured bars as they flickered, like that would somehow affect them. You could see from the greasy smudges on the monitor that he did that a lot. The third man was standing slightly back from the console. From his demeanour and the orders he gave the engineers I guessed he was the new producer, John Crea's replacement, but he looked more like a vice principal—blue polyester shirt, doubleknit slacks, white socks with dress shoes. His hair was gray but worn too long, seventies conservative. He had his meaty, furry arms crossed and a frown on his face that made me want to apologize for coming in tardy. A little goldtinted American flag was pinned on his shirt pocket.

Milo mumbled, "Sorry I missed you last night. I heard you made friends with Cam Compton."

"Somewhere in San Antonio," I said, "there's a big and tall store with a bronze plaque inscribed to you."

Milo frowned and looked down at his outfit—rayon camp shirt, black slacks, oxblood deck shoes that made mine look like poor country cousins. His braided gold neck chain would've hunchbacked a lesser human being.

"You have to get all your clothes custommade," he said, "you might as well get them made nice. Some of us can't just throw on yesterday's jeans and Tshirt, Navarre."

I checked my Triple Rock Tshirt for stains. "I have two of these. What was the crisis that came up last night?"

Miranda kept singing. She opened her eyes every once in a while to glance up nervously at the control booth, like she knew how she was sounding. She looked like she was singing her heart out—taking huge breaths from her diaphragm, scrunching up her face with effort when she belted out the words, but none of the energy of the night before was coming through the speakers. The first engineer tilted his head a little more and said, "I told you she was miked wrong. You and your damn V87s."

The vice principal grunted. The second engineer tapped at the computer monitor a little more.

Milo pointed left with his thumb. We moved a few steps toward the door; just out of earshot from the studio guys.

"Tell me you've decided to help us out," he insisted.

"What happened with you last night?"

He scratched the corner of his mouth, found some invisible particle that displeased him, rolled it in his fingers and flicked it away. "I had a great day. I called around, gently explaining to people that maybe I wasn't exactly sure where Les is. Several major clients bailed. The cops were thrilled. They were about as excited as I thought they'd be. As soon as they get through yawning I'm sure they'll launch a massive manhunt."

Milo glared at me accusingly.

"Honesty is next to godliness," I consoled.

"Then I got a call from our accountant. Not good."

"How not good?"

The two engineers were arguing now about the isolation qualities of wide compression mikes.

"Does she have to sing with the guitar?" the monitor tapper pleaded.

The vice principal shrugged, keeping his eyes sternly on the imaginary detention hall below him. "Lady said she felt more comfortable that way."

The other engineer grumbled. "Does she sound like she's comfortable? "

Milo kept staring forward. "Apparently Les hasn't been telling me everything. Some of the commission checks haven't been going into the main account. A few days ago one of our checks for some equipment rentals bounced. There are also some creditors I didn't know about."

"Bad?"

"Bad enough. The agency costs fifteen thousand a month to run. That's barebones—phone bills, transportation, property, promo expenses."

"How much longer can you keep afloat?"

Milo laughed with no humour. "I can keep the creditors at bay for a while. I don't know how long. Fortunately our clients pay us; we don't pay them. So they don't have to find out right away. But by all rights the agency should've folded at the start of the month.

Les had made arrangements to pay our bills then and there's no way he could have."

"About the time he disappeared."

Milo shook his head. "You had to put it that way, didn't you?"

Miranda strained her way through another verse.

"Look," one of the engineers was saying, "it's a Roland VS880, okay? Pickup isn't the problem here. You don't need the goddamn digital delay if she's singing it right, man.

The lady's a cold fish."

"Just try it," the vice principal insisted. "Put a little through her headphone mix, see if that warms her up."

Finally I told Milo about my last two days.

Milo stared at me while I talked. When I finished he seemed to do a mental countdown, then looked out the Plexiglas again and sighed.

"I don't like any of that."

"You said Les joked about running off to Mexico. If this plan he had to get Sheckly was dangerous, if it went bad—"

"Don't even start."

"Stowing away funds from the agency, pulling deceased identities from personnel files—what does that sound like to you, Berkeley Law? "

Milo brought his palms up to his temples. "No way. That's not—Les couldn't do that. It's not his style to run."

Milo's tone warned me not to push it. I didn't.

I looked back down at Miranda, who was just finishing the last chorus. "How bad will all this affect her?"

Milo kept his eyes closed. "Maybe it can still work. Silo's been paid through next week.

Century Records will need some heavy reassurances, but they'll wait for the tape. If we get a good one to them on time, if we get Sheckly off our backs ..."

Miranda finished her song. The sound died the instant she stopped belting it out.

Nobody said anything.

Finally the engineer asked halfheartedly, "Do another take? We could try to feed her just the basic tracks. Move the baffles around."

Miranda was looking up at us. The vice principal shook his head. "Take a break."

Then he leaned over the console and pushed a button. "Miranda, honey, take a break for a few minutes."

Miranda's shoulders fell slightly. She nodded, then started slowly toward the exit with her guitar.

Milo watched her go out the black curtain.

"You wanted to talk to her," he mentioned.

"Yeah."

"Go ahead, first door on the left. I'd have to be positive with her. Right now that's not possible."

He turned and concentrated on the recording console like he was wondering how hard it would be to lift and throw through the Plexiglas.

18

Miranda was lying on a cot with her forearms over her face and her knees up. She peeped out briefly when I wrapped my knuckles on the open door, then covered her eyes again.

I came in and set my backpack on the little round table next to her. I took out my bag of Texas French Bread pastries and a .22 Montgomery Ward pistol. Miranda opened her eyes when the gun clunked on the table.

"I thought you could use some breakfast," I said.

She frowned. When she spoke she exaggerated her drawl just a little. "The croissants put up a fight, Mr. Navarre?"

I smiled. "That's good. I wasn't sure you'd have a sense of humour."

She made a square with her arms and put them over her head. She was wearing a cutoff white Tshirt that said COUNTY LINE BBQ on it, and there was a small oval of sweat sticking the fabric to her tummy where the guitar had been. The skin under her arms was so white that her faint armpit stubble looked like ballpoint pen marks.

"After the last few mornings I've had in the studio," she said, "you've got to have a sense of humour."

"Hard to get the sound right. The engineers were saying something about the microphones."

Miranda stretched out her legs. She looked at her feet, then kicked her Jellies off with her big toes. "It's not the microphone's fault. But that ain't what you're in here to talk about, is it? I'm supposed to ask you about the gun."

I offered her a chocolate croissant. She seemed to think about it for a minute, then swung her legs onto the floor and sat up. She shook her head so her tangly black hair readjusted itself around her shoulders. She moistened her lips. Then she bypassed the chocolate croissant I was holding and went straight for the only ham and cheese.

Damn. A woman with taste.

She nudged the .22 with her finger. Country girl. Not somebody who was nervous around guns. "Well, sir?"

"It's the gun somebody used to shoot at John Crea. I found it in the thirdfloor garbage bin at the parking lot next door."

Miranda tore a corner off her croissant. "Somebody just left it there? And the police didn't—"

"Hard to underestimate the stupidity of perps," I said. "Cops know perps are stupid and they try to investigate accordingly, but sometimes they still underestimate. They overlook possibilities nobody with any sense would try, like using a .22 Montgomery Ward pistol for a hundred yard shot and dropping the gun in the garbage on their way to the elevator. Police are thinking the shooter must've used a rifle and carried it away with him and ditched it somewhere else. That's what a smart person would do. Most people who get away with crimes, they don't do it smart. They do it stupid enough to baffle the police."

"So—you taking the gun to the police?"

"Probably. Eventually."

"Eventually? After what happened to poor Julie Kearnes, shot the exact same way—"

I shook my head. "Poor Julie was killed by a professional. Whoever left this was an amateur. Similar incidents, both people connected to you, but they weren't done by the same person. That's what I don't get."

"If I could help—"

"I think you can. You know Sheckly a lot better than I do."

Her expression hardened. "I don't know him that well. And no, he wouldn't have anything to do with this."

"Somebody's trying to make things difficult for you since you started courting Century Records. You have any theory?"

Miranda took a bite of my ham and cheese croissant. She nodded her head while she chewed. After she swallowed she said, "You want me to admit Tilden Sheckly is a hard customer. Yes, sir. He is. He's got a bad temper."

"But—"

She shook her head. "But Sheck wouldn't do those things. He's known Willis, shoot—he's known all the families in Avalon County for a million years. I know what people think, but Sheck's always been a gentleman with me."

She looked up at me a little tentatively, like she was afraid I might contradict her, might ask her to prove it.

"If he's such a great guy," I said, "why did you sign with Les SaintPierre?"

Miranda pressed her lips together, like she'd just put on lipstick.

"You heard of that lady who played out at the Paintbrush a few nights ago, Tammy Vaughn?"

"I saw her."

Miranda raised her eyebrows. Apparently she hadn't figured me for a country music fan. I liked her for that.

"A year ago," Miranda continued, "Tammy Vaughn was where I am. She played mostly local gigs—South Texas, Austin. Mostly dance halls. Then she got a good agent and signed with Century Records. They're the only major label with a Texas office, did you know that? They've started paying attention to the talent down here, picking out the best, and sending them on to Nashville. Now Tammy's playing for fifteen thousand a night. She opened for LeAnne Rimes in Houston. She's got a house in Nashville and one in Dallas."

"And Sheckly can't do that for you."

"My dad's barely paid the mortgage on his ranch for as long as I can remember. He does contracting all day and music all night and he won't ever be able to retire. We won't even talk about Brent. The idea of being able to help them out..."

"You're telling me it was just the promise of money?"

She thought about that, apparently decided to be honest. "No. You're right. I signed with Les because of the way he talked, that first time we met. Something about Les SaintPierre—you can't just tell a fella like that no. Besides, Sheck or not—sometimes you have to make choices for your career. You don't always get to make everybody happy."

"Allison," I said.

Miranda frowned at me. "Pardon?"

"That's an Allison SaintPierre line, isn't it?"

Miranda looked uncomfortable. She put the croissant down halfeaten and brushed her fingers. She stared at the .22.

"What about Cam Compton?" I asked.

Miranda took her eyes from the gun. Slowly she worked up a smile. "Does he have it in for me? No, sir. Cam—I know you ain't going to believe this after last night, but Cam is basically harmless. You know how they say, dogs always look like their masters?"

"Uhhuh."

"I'm serious now. Cam's nothing but the poodle version of Tilden Sheckly. He tries awful hard to look wicked and dangerous and like he's got all this violent side ready to let loose, but comes right down to it, he wouldn't do nothing if Sheck didn't say 'sic 'em.'

Even then he wouldn't have the brains to do it right."

"You think so. Even after last night."

"I know. Cam's got himself a little music store down in S.A., bought it after he got this one hit record over in Europe somewhere, about ten years ago. Cam'll go back to that, go back to working the house band at the Paintbrush. Two weeks from now he'll forget all about Miranda Daniels. He's got nothing riding on my chances one way or the other."

Sounding pleased, like she'd just reconvinced herself, Miranda stretched back out on her cot and examined the ceiling. "You know Jimmie Rodgers recorded his last ses

sion two days before he died? The tuberculosis was eating up his lungs so bad he had to lay down in a cot in the studio between songs, just like this here. I keep thinking about that."

"Should I put the gun away?"

She smiled nicely. "No, sir. It's just that Jimmie Rodgers' last sessions sound so good.

It's depressing."

"You're not doing too badly."

She didn't look encouraged.

"Your family supportive about your career?" I asked. "Your mom?"

She studied seven or eight ceiling tiles. "She's dead. A long time ago. Milo didn't tell you that?"

I shook my head. "Sorry."

"I* guess there's no reason he should have. I don't think about it much."

She moved her lips a little more, like she still couldn't get them aligned quite right. "But that wasn't your question again. Yes, Dad is real supportive. He's amazing, how he keeps going. You can say what you please about Tilden Sheckly, Mr. Navarre, but Sheck encouraged Dad to stay with me when we put the band together, to play at any gig he could, and that's been my biggest comfort. We got a standin bassist for him when we do bigger gigs, but still—he's an old workhorse. If it hadn't been for his music when I was growing up, all the Ernest Tubb records and the Bob Wills—that and my mother singing in the kitchen—"

She drifted off. I concentrated on my croissant and let her mind work around to wherever it wanted to go for a few moments.

"What about Brent?"

Miranda's eyes became clearer and cooler. "He's supportive."

"You didn't seem happy with him last night."

"You have siblings?"

"Brother and a sister. Both older."

"You get along with them all the time, Mr. Navarre?"

"Point taken."

She smiled dryly. "You seem like a nice fella. You were asking last night about 'Billy's Senorita.' That's about the only song I wrote myself, Mr. Navarre. The others are Brent's, did you know that? "

I said I didn't. I tried not to look too surprised.

"It's funny about how they sound in the studio," she said at last. "Ace was telling me—"

"Ace?"

She did a mental rewind, then smiled. "John Crea. My old—my exproducer. He liked to be called 'Ace,' what with that flight jacket and all."

"I bet he did."

"Anyway, Ace was telling me how some singers have to reproduce what makes them so good onstage in order to sound right in the session. Drugs, audiences screaming at them, what you please. Some got to turn their backs to the control booth or sing in the dark. Ace told me about this one rock and roll fella had to hang upside down to get the blood going right before he sang. I ain't kidding you. Ace said whatever I needed to make the songs sound right, he'd make it happen."

"Do you know what you need?"

I could see her framing the right answer, her face hardening up with a level of seriousness that didn't seem natural for her. Then she looked at me and decided to discard it. She softened again and smiled. "No. I just keep imagining myself hanging upside down in the dark with a bottle of whiskey, singing—Billy rode out last night..

She got that far singing the line, then cracked up. "Don't help me to sound any better, but it sure keeps things lighter in my mind."

A buzzer sounded down the hall from the recording area. Miranda puffed up her cheeks and exhaled.

"That'd be the master, calling me back. You like to stay—watch me sweat out a few more bad takes?"

I shook my head. "I should pay some other visits in town before I head back to San Antonio. You didn't answer my question."

She looked me in the eyes. She tried to keep the smile playful, but it was a strain for her. "What question was that, Mr. Navarre?"

"Who do you think is causing you so much grief, if not Sheckly or Cam? Anybody you know who would like to see you miss your big chance? "

She looked down, her hands on the edge of the cot and her shoulders bending into a U. She was short enough that she could hang her legs over the side and sweep the flats of her feet back and forth.

"I didn't mean to undercut Allison's invitation to our party," she said. "You're welcome to come tomorrow."

"Thanks."

"Allison has been my best friend the last few months. She's been so good to me."

"You're still not answering my question."

When Miranda stood, we were close enough to slow dance. I saw green flecks in her brown irises I would never have noticed otherwise. She spoke so softly I barely heard her.

"The funny thing is, Allison SaintPierre's about the only person who truly scares me to death. You asked and I told you. Isn't that a terrible thing to say about a friend?"

Milo Chavez wrapped his knuckles on the door. "There's the champ."

He moved past me and wrapped a huge arm around Miranda's shoulders. Miranda unlocked her eyes from mine and smiled up at Chavez. Her head rested on his chest.

She let some of her tiredness show.

"It's going pretty rotten, Milo."

"No," Milo insisted. He'd found his positivity. He beamed the best smile I'd ever seen him beam. I was almost convinced myself, almost ready to believe our recent conversation about his missing boss and the missing funds had been a daydream.

"You wait, Miranda. Give it another week, you'll see. You'll be amazed. You're going to listen to yourself on the finished tape and think: 'Who's that star I'm hearing?' "

Miranda tried for a smile.

As they were walking down the hall together, Milo was rubbing Miranda's shoulders like a boxing coach and telling her how great she was doing. Miranda took one backward look at me, then returned her attention forward. The buzzer blared again, calling them inside.