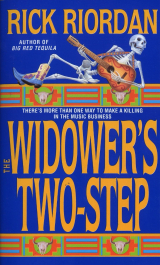

Текст книги "The Widower's Two-Step"

Автор книги: Rick Riordan

Жанры:

Разное

,сообщить о нарушении

Текущая страница: 3 (всего у книги 23 страниц)

"You know how to flatter a guy."

He reached into his pocket and pulled out a money roll only Milo could've carried without his pants bulging obscenely—fiftydollar bills wrapped as thick as a Coke can.

"Your boss doesn't like the case, we can cut out the middle man."

"No," I said. "I don't have my own license. At this point it looks like I might never."

"That's just as well."

"I told you, I'm thinking about getting out of this line of work."

Milo put the cylinder of money sideways on the table and rolled it in my direction.

"You're going to look into Kearnes' murder anyway, Navarre. You couldn't put down something that happened on your watch—I know you better than that. Why not let me pay you?"

Maybe I felt like I owed him. Or maybe I was thinking about how long I'd known him, off and on since high school, always reconnecting with each other at the least opportune moments like bad acoustical echoes.

Or maybe I'm kidding myself. Maybe what swayed me more was that roll of money—the prospect of paying my rent on time for once and not having to borrow gro

cery money from my mother.

I heard myself saying, "What exactly do you want me to do?"

7

The Les SaintPierre Talent Agency was a gray and maroon Victorian on West Ashby, across the street from the Koehler Museum.

Even without a sign in front you could tell the old residence had been converted for business. The powercolour combination, the uniform blinds on the windows, the wellkept but totally impersonal landscaping, the Texas flag windsock hanging on the empty front porch—it all screamed "office building."

There were two cars already parked at the bottom of the hill in front. One was a tan Volvo wagon. When I met Milo on the sidewalk he was staring at the other– a glistening black pickup truck that looked like it had been converted at great expense from a semi rig. It had wheels just shy of monster size, tinted windows with security alarm decals on the corners, orange pin striping, mud flaps with silver silhouettes of Barbie doll women on them. The cab looked like it could sleep four comfortably.

Milo said, "This isn't my day."

Before I could ask what he meant, he turned and lumbered up the steps.

Inside, the Victorian was all hardwood floors and creamcolored walls. A staircase led up from the main foyer. The double doorway on the right opened into a reception area with a couple of wicker chairs, a mahogany desk, a fireplace, and a Turkish rug. A very big Anglo man in his early fifties was sitting on the edge of the desk, talking with Gladys the receptionist.

When I say very big and I'm standing next to Milo I have to correct myself. This guy wasn't like Milo, but he was big by any other definition. Tall and barrelchested. Thick neck. Powerful hands. He had the build of a derrick worker.

Despite the heat he wore a denim jacket over his white shirt, new blue jeans, black Justin boots. He was twirling a Stetson on one finger while he talked.

When he saw Milo, his smile hardened.

"Hola, Mario."

Milo walked placidly to the desk and picked up a stack of mail. He didn't look at his visitor. "Fuck you, Sheckly. You know my name."

"Hey now—" Sheckly spoke with the twangy, hard edged accent of a GermanTexan, someone who'd grown up in the hill country around Fredericksburg, where many of the families still spoke a brand of cowboy Deutsch. "Play nice with me, son. I just dropped by to see how things were coming along. Have to make sure you're doing right by my girl. You remind Les about that contract yet?"

Milo kept flipping through his mail. "Les is still in Nashville. I'll tell him you dropped by.

The contract's right next to the toilet where he left it."

Sheckly's laugh was a rich chuckle. He kept twirling the Stetson. "Come on now, son.

You want to dispute our agreement, you've got to put me in touch with the boss man.

Otherwise I'm expecting Miranda in the Split Rail studio come November first and I'll tell you what else—you send Century that demo and I'll send them a copy of my contract, see if they want to sink their money into a girl who's gonna bring their legal department a mess of business."

Milo opened another letter. "You know where the door is."

Sheckly got up from the desk slowly, told the receptionist, "You think about it," then started walking out.

In front of me he stopped and offered to shake. "Tilden Sheckly. Most people call me Sheck."

Up close, it looked like all the unnecessary pigments in Mr. Sheckly's face had drained into his tan, which was dark and perfect. His eyes were so bleached blue they were almost white. His lips had no red at all. His hair had probably been thick and chocolaty at one time. It had faded to a dusty brownishgray, uncombable tufts that looked like clumps of moth wings.

I told him my name.

"I know who you are," he said. "I knew your father."

"Lots of people knew my father."

Sheck grinned, but it wasn't friendly. He looked like I'd missed the joke. "I suppose so.

Most of them didn't contribute as much as I did."

Then he put on the Stetson and said goodbye.

When he was gone Milo turned to Gladys. "What did he mean, 'think about it'?"

Gladys said Sheck had offered her a secretarial job with a fifty percent pay raise. She said she'd turned him down. She sounded a little wistful about it.

Milo stared at the space on the desk where Sheck had been sitting. He looked like he was contemplating putting his fist through the mahogany. "You do those calls yet?"

Gladys shook her head. She launched into a long story about how some club owner in San Marcos had called and complained that Eli Watts and His Sunrisers had torn up the hotel room he'd rented for them and now he wanted the agency to pay the damages. Gladys had spent her entire morning trying to smooth things out.

I thought the desk was going to get it, but slowly Milo's meaty fists unclenched. He mumbled something under his breath, then led me down the hall and into his office.

Everything in the converted parlour had been custom made for Milo's comfort—two massive red leather chairs, a halfton oak desk with a twentyoneinch computer monitor and a candy bowl the size of a basketball, bookshelves that started as high as most bookshelves stopped and went all the way to the ceiling. The only thing small was Milo's rosewood Yamaha acoustic in the corner, the same guitar he used to bring on our drunken college road trips into the Sonoma wine country. There was still a crescentshaped dent near the sound hole where I'd thrown a beer can at Milo and missed.

I sat across the desk from Milo.

On the right wall were framed pictures of Les Saint Pierre's past and present artists. I recognized several country stars. Nobody recent. Nobody I would've considered huge.

Prominently displayed in the centre was a photo of the Miranda Daniels Band—six people at a bar in a honky tonk, all facing out toward the camera and trying to look casual, like they lined up that way every night. Julie Kearnes and Miranda Daniels were shoulder to shoulder in the middle, sitting up on the bar with their cowboy boots crossed at the ankles and their denim skirts carefully arranged to show some calf.

Miranda looked about twentyfive, her hair dark and shoulderlength, just curly enough to look tangled. Petite body, almost boyish. An unremarkable face. In this shot she was smiling, looking out the corner of her eye at Julie Kearnes, who got caught midlaugh.

With the air brushing you almost couldn't tell Julie was older than Miranda.

The two good old boys on their right were in their sixties. One had a trimmed white beard and a healthy belly. The other was tall, with no body fat at all and thinning, greasy black hair. The men on the left were younger, both in their forties, one with longish blond hair and a thick build and an Op Tshirt, the other with dark curly hair and a black cattleman's coat and black hat and a scowl that was probably supposed to be James Deanesque but didn't quite make it. The cattleman looked quite a bit like Miranda Daniels, but twenty years older.

On the wall behind the picture was a pale square halo that told me the band's photo had superseded somebody else's whose picture had been slightly larger.

Milo followed my eyes to the photo on the wall.

"They're not important," he assured me. "The old fart with the white beard is Miranda's dad, Willis. The guy in the Wyatt Earp outfit is her big brother, Brent. You know—knew—Julie. The thin greasy one is Ben French. The burly surfer reject is Cam Compton."

"Miranda's brother and her dad are in the band?"

Milo spread his hands. "Welcome to Hillbilly World. Funny thing is, until about two years ago Miranda was considered the w«talented one in the family. Then Tilden Sheckly, the lovely human being you just met, took an interest in her."

"Sheckly is part of your problem."

Milo reached for his candy bowl. "Butterscotch or peppermint?"

"Definitely butterscotch."

He threw me a roll of midget Life Savers, then took two for himself. "Sheck owns that big honkytonk on the way to Medina Lake, the Indian Paintbrush. You know the place?"

I nodded. Anybody who'd ever driven toward Medina Lake knew the Indian Paintbrush. Plopped next to the highway in the middle of several hundred acres of rock and dirt, the dance hall looked like the world's largest portable john—a white corrugated metal box big enough to accommodate a shopping mall.

"Paintbrush Enterprises," I speculated. "The company who's been sending Julie Kearnes biweekly deposits."

Milo stared at me. "Do I want to know how you got access to her bank account?"

"No."

He cracked a smile. "Sheck is known for promoting pet acts. Usually pretty younger women. He lets them open for his headliners on weekends, sometimes gets them into his house band. Sooner or later, he gets them into bed. He manages their careers for fifty percent of the profit, milks them as long as he can. Once upon a time that was Julie Kearnes. Julie acted like a good girl, so even when she stopped bringing in crowds Sheckly kept her on the payroll—doing his spreadsheets, designing promotionals, occasionally opening for somebody. Miranda Daniels was going to be Sheckly's next project. Then Les signed her out from under Sheck's nose."

"And Sheckly still thinks he owns her."

Milo nodded.

"And you and Les disagree."

Milo unwrapped his Life Savers and dumped them in his mouth. He brushed his hands, slid out the side drawer of his desk, and produced a legalsized document.

"You heard Sheckly mention a contract just now?"

I nodded.

Milo slid the paper across to me. "Before we signed Miranda Daniels, Sheck had all kinds of plans for her. He was going to put her first album out on this little regional label he owns—Split Rail Records. He was going to tour her around small clubs in the States and Europe, be her sugar daddy. He probably stood to make about a quarter of a mil off her. Miranda stood to make shit—minimal sales and no national exposure.

That was Sheck's plan, only he never put anything in writing. Probably he couldn't imagine Miranda'd be crazy enough to cross him.

"Then Les signed her away from him. Sheck screamed and hollered but there wasn't much he could do. The band was mostly Sheck's old protégés—Julie, Cam Compton, Ben French—but there wasn't much they could do either. They went along with the new arrangement. It wasn't until Les got Century Records interested in hearing Miranda's solo demo tape that Sheckly suddenly waltzed into our office with that.'"

I scanned the document. It was a poorquality photostat of an agreement dated last July, signed by Tilden Sheckly and Les SaintPierre as Miranda's manager. All the legalese seemed to boil down to one main promise: that Tilden Sheckly would have first option on any performances or recordings by Miranda Daniels for the next three years.

I looked at Milo. "This means Sheckly could veto the deal with Century Records?"

"Exactly."

"Is the contract valid?"

"Hell, no. Les screamed bloody murder when he read it. It's a forgery, the oldest bluff tactic in the book. Sheckly's just trying to scare away a potential buyer and Les wasn't about to fall for it."

"So what's the problem?"

"The problem is it's a very effective bluff. Major labels are skittish about new talent. To prove the contract invalid Les would have to go to court, make Sheckly produce the original document. Sheckly could delay for months, drag things out until Century lost interest in Miranda or found another place to sink their money. The window of opportunity for a deal like this shuts pretty damn quick."

"And Les isn't around to challenge it."

Milo held his hand out for the contract. I gave it back. He stared at it distastefully, then folded it and filed it away.

"Les said he had a plan to get Sheckly's balls in a squeeze, something to make Sheck withdraw the contract and do anything else Les told him to do. Les had been spending a lot of time with Julie Kearnes since we took over management of the band. Les said she was going to help him out."

"Blackmail?"

"Knowing Les, I don't doubt it. I warned him to be careful of Julie Kearnes. She'd been working too long with Sheckly; she was still taking his money. Julie was sweet to Les but I saw her other side. She was bitter, shorttempered, jealous as hell. She complained about how Miranda was going to go down the same way she had, that it was just a matter of time. Julie said Miranda should be more grateful, keep Julie around for all her experience once Miranda signed with Century."

He sighed. "Les wouldn't listen to me about Kearnes. They'd gotten pretty close over the last month. I'm not sure how close, to tell you the truth. Then he disappeared. I was hoping if you kept tabs on Julie"—Milo rapped his knuckles lightly on the desk, he scowled—"I don't know what I thought. But it looks like Sheckly got his problems solved very neatly. First Les. Now Julie. Whatever they were planning to do to get Sheck's claws off Miranda Daniels, it isn't going to happen now."

I found myself looking again at the photo on the wall—at the unimpressive face of Miranda Daniels. Milo must've guessed my thoughts.

"You haven't heard her sing, Navarre. Yes, she's worth the trouble."

"There's got to be other country singers around. Why would a guy like Tilden Sheckly get bent out of shape over one that broke out of the stable?"

Milo opened his mouth, then closed it again. He looked like he was reorganizing what he wanted to say. " You don't know Sheck, Navarre. I told you he lets some of his wellbehaved artists like Julie Kearnes stick around after they're washed up. One of Sheck's less cooperative girls ended up at the bottom of a motor lodge pool. Freak swimming accident. Another male singer who tried to get out from under Sheckly's thumb was busted with a gram of cocaine in his glove compartment, got three years of hard time. The deputies in Sheck's county handled both cases. Half of the Avalon Sheriff's Department works security at the Paintbrush on their off hours. You figure it out." "Still—"

"Les and Sheck had a history, Tres. I don't know all the bloody details but I know they've been at each other's throats over one deal or another for years. I think this time Les went a little too far trying to twist Sheckly's arm. I think Sheckly finally decided to solve the problem the way Sheck knows best. I need you to tell me for sure."

I unwrapped a butterscotch and put it in my mouth. "Three conditions."

"Name them."

"First, you don't lie to me. You don't withhold anything again. If I ask you for a top ten list you give me eleven items."

"Done."

"Second, get better candy."

Milo smiled. "And third?"

"You bring in the police. Talk to the wife, set it up any way you want, put the best face on it, call it a silly necessity to your clients—but you level with SAPD about SaintPierre being gone. You have to get his name into the system. I won't poke around for two or three more weeks, then find out I've been failing to report another homicide. Or a killer."

"You can't seriously think Les—"

"You said Julie and Les were getting close. Julie is now dead. If the police start looking around and can't find SaintPierre, what are they going to think? You've got to level with them."

"I told you—I can't just go—"

I got my backpack off the floor and unzipped the side pocket.

It was an old green nylon pack, a holdover from my grad days at Berkeley. It served me well in investigative work. Nobody cares much about grad students with backpacks. Nobody thinks you might be carrying burglar tools or recorders or fat rolls of fiftydollar bills.

I took out Chavez's money and put it on his desk. Then I stood up to leave.

"Thanks for the chat, Milo."

Milo leaned back and pressed his palm to the centre of his forehead, like he was checking for a fever. "All right, Navarre. Sit down."

"You agree?"

"I don't have much choice."

The phone rang. Milo answered it with a "hello" that was mostly growl.

Then his entire disposition changed. The emotion drained out of his voice and his face paled to the colour of caffe latte. He leaned forward into the receiver. "Yes. Yes, absolutely. Oh—no problem. Les, ah– No, no, sir. What if—no, that's fine."

The conversation went on like that for about five minutes. Somewhere in the middle of it I sat back down. I tried not to look at Milo. He sounded like an overwhelmed tenyearold listening to Hank Aaron explain why he couldn't sign the kid's baseball card.

When Milo hung up he stared at the receiver. His fingers wrapped around the wad of money, almost protectively.

"Century Records?" I asked.

He nodded.

"It's getting hard on you."

"I didn't want to run the entire agency, Navarre. We've got seven other artists touring right now. I've got promoters breathing down my neck about deals Les didn't even mention to me. Now Century Records—I don't know how I'm going to hold the deal together when they find out Les is gone."

"So walk away."

Milo seemed to turn the words around in his head. They must have rolled unevenly, like rocks in a tumbler.

"What do you mean?"

"Let the agency collapse if it has to. You've got your law degree. You seem to know what you're doing. What do you need the charades for?"

Milo shook his head. "I need SaintPierre's clout. I can't do it on my own."

"Okay."

"You don't believe me."

I shrugged. "Somebody once told me my problem was thinking too small—that I should just take a chance and throw myself into the kind of work I really liked, the hell with what people said. Of course that advice got me a knife in the chest a week later.

Maybe you don't want to follow it."

Milo's eyes traced a complete circle around the room, like they were following the course of a miniature train. When they refocused on me, his voice was tightly con

trolled, angry. "Are you going to help me or not?"

"The Century Records deal is that important to you?"

Milo made a fist. "You don't get it, do you, Navarre? Right now Miranda Daniels is making about fifteen hundred a gig—that's payment for the whole band, if she's lucky.

She has minimal name recognition in Texas. Suddenly Century Records, one of the biggest Nashville labels, says they're interested enough to offer a developmental deal.

They give her money for a demo, thirty days in the studio, and if they like what comes out of that, she's guaranteed a major contract. That would mean over a million dollars up front. Her price per gig would go up by a factor of ten and my commission would go up with it. Other people in the industry would suddenly take me seriously, not just as Les SaintPierre's stepandfetch it. You have any idea what it's like having somebody dangle that possibility in front of you, and knowing that a jerk like Tilden Sheckly could screw it up?"

I nodded. "So what's our deadline?"

Milo looked down, unclenched the fist, rubbed his hand flat against the desktop.

"Miranda's master demo is due to Century next Friday. I've got that long to get the recording redone and to figure out a way to keep Sheck quiet about this forged contract. Otherwise there's a good chance Century will renege on their offer. Ten days, Navarre. Then, if all goes well, maybe I'll take your advice. I'll ask Miranda to let me represent her and let the rest of the agency go to hell."

There was a knock on the door. Gladys stuck her head in and said that Conwell and the Boys were here for the five minutes Milo had promised them last week. They'd brought a tape.

Milo started to tell Gladys to send them away but then changed his mind. He told her they should come on down.

When she closed the door again Milo said, "Unsolicited demo tapes. I could build a house out of what we've got in the back room, but you never know. I try not to blow people off."

He pushed the money back to me.

"Just ask Gladys for the files on your way out—she'll know what you mean. It's some background material I put together, stuff you would need to know."

"You assumed I would stay on the case."

"Read the files over. And it's about time you met Miranda Daniels. She's playing at the Cactus Cafe in Austin tomorrow night. You know the place?"

I nodded. "Julie Kearnes' death isn't going to make you cancel the gig?"

My comment might as well have been a sneeze for all it registered. "Just come check Miranda out. See what the fuss is about. Then we can talk."

I didn't protest very hard. I dropped the roll of fifties back in my bag and promised to think things over.

When I was at the door Milo said, "Navarre."

I turned.

Milo was staring through me, into the hallway. "It'll be different this time. It's not like—it's not like I feel good about the way things happened back then, okay?"

It was the closest he'd ever come to an apology.

I nodded. "Okay, Milo."

Then Conwell and the Boys were pouring in around me, all grins and new haircuts and coats and ties. Milo Chavez switched moods and started telling the musicians how glad he was they could drop by, how sorry he was that Les SaintPierre was out of town.

I heard the easy laughter of the meeting all my way down the hall.