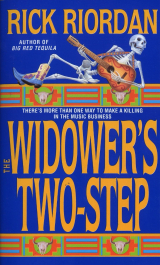

Текст книги "The Widower's Two-Step"

Автор книги: Rick Riordan

Жанры:

Разное

,сообщить о нарушении

Текущая страница: 10 (всего у книги 23 страниц)

He walked up to the skinny kid and lifted him by his jacket with one hand. Maybe that would've been impressive if the kid hadn't weighed ninety pounds, or if Chico hadn't planted his legs apart and given Vega a beautiful opportunity to knee him in the balls.

Vega's knee was mostly bone, and what he lacked in weight he made up for in ferocity.

As he kneed Chico, Vega's face tightened and his teeth clenched so hard his tuft of beard almost touched his lower lip.

Chico grunted, dropped the kid, then doubled over and started turning around in slow motion. Chico's face was the same colour as his bandanna. One of the fullbacks kicked him from behind and Chico went sideways onto the asphalt groaning: "Mierda, mierda."

I looked at Ralph. "He's new."

"Yeah."

Vega adjusted his baggy clothes and sat back down, smiling again. He rubbed his little beard and told his buddies what a big tough pachuco Chico was. They laughed.

"Oh, man," said Vega, "you had some customers come by today, Boss, but they didn't look like a good type of people, right? We told them no way. We're looking out for you good."

About then a scrawny grayhaired man shuffled out of the pawnshop, looked at Ralph a little fearfully, and started apologizing in Spanish.

"Mr. Arguello, I swear I didn't know they were out here. I chased them off twice already."

Then the old man started waving a rolledup newspaper at the three kids, halfheartedly telling them to go away. Nobody paid him any attention. The kids were looking at the .357 Magnum Ralph was now holding.

"You know, vato," Ralph said to me casually, "used to be you had just La Familia coming to you. Least they were adults, right? Now you've got these pinche kids, think just because they can beat up their math teacher they got a right to protection money.

Sad, man. It's really sad."

Vega looked at the gun in Ralph's hand like it was a big joke. "You gonna shoot me, Boss Man?"

Vega wasn't afraid. Maybe you don't get afraid when you're seventeen and you've got your set behind you and you know guns the way other kids know skateboards.

On the other hand, I didn't like the way Ralph was smiling. I'd seen Ralph use a .22 like a staple gun on a guy who'd touched his girlfriend in a bar. Ralph had been smiling the same way as he stapled the guy's palm flat against the wooden counter.

"We got guns," Vega said. "Like in the middle of the night. Outside your house, right?"

Chico was on his hands and knees now, taking noisy breaths and mumbling that he was going to kill them.

Vega looked down and said, "Good dog."

That got another laugh from his fullbacks.

Ralph was perfectly still, frozen. I figured I had a few seconds before he made up his mind what part of this kid's body he was going to blow a hole in.

"You three need to leave," I said.

Vega looked at me for the first time. "Who's this, Boss Man? This your girlfriend?"

Before Ralph could shoot, I grabbed Vega's ankles and pulled. The kid went back off his elbows and hit his head on the cement edge of the stairs. I dropped him just as his fullback buddies realized they needed to act.

I don't often use Ride the Tiger. Usually you don't get opponents attacking the way a tiger does, from above. As the first kid jumped me I slid into bow stance and swept my arms up in a circle, my right hand rolling against his chest and my left hand against his leg. He flew over me like he'd been bounced over the top of a spinning wheel. I didn't look behind to see how he landed on the asphalt of the parking lot.

The second kid tackled me from the side. I hooked his baggy jacket, turned my waist hard, and flipped him over my knee. He landed on his butt with a muffled crack.

By the time I saw Vega move out of the corner of my eye and saw the flash of metal and I turned, it would've been too late.

There was a click.

The kid was propped up on one elbow, a long knife in his hand, the tip frozen six inches away from my thigh. Ralph was kneeling next to him, smiling calmly, the muzzle of his .357 pressed hard into Vega's eye. Vega's head tilted up at the same angle as the barrel, as if he was looking into the eyepiece of a telescope. His free eye was twitching violently.

"The man put you on the ground, ese," Ralph told him amiably. "You got any sense, that's where you stay."

The three of us stayed frozen for a couple of centuries. Then, finally, Vega's knife clattered against the pavement. "You're dead, Boss Man. You know that?"

Ralph grinned. "Twenty or thirty times, ese."

Ralph took Vega's knife, then stood up and put away Mr. Subtle. I looked around. The guy I'd knocked on his butt was still on his butt. He was staring at me. His eyes were watering and he was tilting sideways, trying to get away from the pain. The guy I'd thrown into the parking lot was trying to stand up, but it looked like his left shoulder was glued to the pavement. I think maybe his collarbone was broken.

I got the kids to their feet and started herding them out of the lot.

They shuffled down Bandera, Vega shouting back at me that they knew where I lived and my family was dead. I called after Vega that his buddy would need a doctor for the collarbone. Vega shot me the finger. His eye was still twitching from the cold, oily nudge of the .357 muzzle.

When I came back to the front door of Number Fourteen, Chico was sitting on the sidewalk, trying not to throw up. He looked up at me resentfully.

"Lucky shot," I said. "I thought you had him."

The old man with the rolledup newspaper was trying to explain to Ralph that everything was fine and he would have it under control from now on. He looked nervous.

Ralph grinned at me and brought out a clip of money and peeled off a few bills.

"Least I can do, man."

The going price for beating up teenagers was two hundred dollars. A lot more expensive than a few .357 rounds. I gave the money back to Ralph.

"No thanks."

Ralph shook his head in amazement. "So you wouldn't be into it, eh, vato "

He laughed. Then he turned and went into Number Fourteen to check on business.

22

There are definite disadvantages to teaching a fouryearold to tell time. As soon as I walked in Erainya's front door at six that evening Jem looked up at me from the diningroom table, pointed at his Crayola Swatch, and told me I was late. We now had only thirty minutes before our movie started at the Galaxy. He didn't want to miss the previews.

He scooted out from the table and rushed toward me. Instead of our usual fulltackle hug he screamed "Watch!" as he ran, then proved how well he'd been practicing his moves by landing a flying kick in my crotch.

There are also disadvantages to teaching a fouryear old martial arts.

I wiped away a few tears and limped with him into the kitchen, assuring him he was learning the basics just fine.

The kitchen smelled like burnt fila and garlic. It always smelled like Erainya had just been cooking, though I'd never actually caught her doing it. I suspected she'd snuck an entire sweatshop full of Greek cooks back from the old country and kept them locked in the basement when she had company over. Of course this was the same woman who'd shot her husband, so I'd never gotten the courage to actually check her basement. No telling what or who else I'd find down there.

Erainya handed me a threesection paper plate loaded with Mediterranean food. It was so thickly covered with Saran Wrap I couldn't tell exactly what was underneath the wrap. I only knew it was food because Erainya handed me a plate like that every time I came over. Apparently my uncertain employment status hadn't changed the ritual.

"Just in time," I said. "I was beginning to think I might have to go shopping this month."

"Ah." She slapped the air next to her ear, but she did it listlessly, like her heart really wasn't in it today. She was wearing a pullover black shirt and dark slacks, which meant something was up for tonight. Erainya only forgoes the standard Tshirt dress when she knows she's got some crawling or running or breaking in to do. "Just leftovers.

Some kibbeb. Dolmades. Spanakopita. There's a little melitzanosalata—what's . . .

eggplant salad, I guess you'd say."

Erainya's first language was English, but every once in a while she likes to forget how to translate something from Greek. She says thinking in Greek clears her soul.

Jem raced to the bedroom to get his sneakers. When he disappeared down the hallway Erainya said, "You thought things over, honey? About the job?"

"I'm thinking. I have an interview lined up. For a college position."

Erainya gave me the black eyes. "I thought you couldn't stand the idea of a dusty office and a tweed suit."

"Maybe that was sour grapes. Nobody ever offered me a dusty office and a tweed suit."

Erainya slapped air. "Not that I care—not like I want you back if you won't work right.

I'm not losing my license over you being an idiot, honey."

"Sam Barrera speak to you again?"

"I don't know nothing about Sam Barrera's cases and I don't know nothing about what you're doing on your time off, you understand that?"

"Sure."

Erainya glared at the dishrags. "I'm not going to let that ouskemo tell me what to do, neither. Maybe he's got some friends in a lot of places. He doesn't own me."

I nodded. We were quiet, listening to Jem throw toys and other large heavy objects around his bedroom, apparently looking for just the right fashion statement footwear.

"Be good to know some background on a guy named Tilden Sheckly," I said. "About some shipments he's been processing through his dance hall, especially any connections he might have in Europe. Like for instance if your friend in Customs knew anything—what's her name?"

"Corrie. I didn't hear any of that."

I agreed that she hadn't.

Jem came back wearing purple Reeboks. He showed me how the heellights flickered when he bounced up and down. He'd also put a Casper the Ghost mask on his head with shafts of his thick black hair sticking out of the eyeholes. I told him he looked great.

Erainya started loading up her purse while Jem told me about what his Halloween costume was going to be. The costume apparently had nothing to do with the Casper mask. He told me how many hours and minutes were left until six o'clock Sunday, when he was going trickortreating. Then he told me about the movie he was taking me to—something with marsupials that transformed into cosmic warriors.

Erainya packed her cassette recorder, her Mace canister, her obligatory box of green Chiclets, and five Kleenex folded into triangles. She deliberated over her key chain, rubbing her thumb on the little gold key that opens her gun cabinet.

Then she looked up and realized I was watching her.

Her eyes turned hard as obsidian. She stowed the keys in her purse and zipped it.

"Is two hours going to be enough time?" I asked.

I tried to keep my voice casual, disinterested. Erainya responded the same way.

"Sure, honey. Fine."

Jem gave up explaining the virtues of outer space marsupials to me. He climbed back onto a stool at the kitchen counter and started colouring a picture of Godzilla.

"The Longoria case?" I asked.

Erainya hesitated long enough to confirm it. "It's nothing, honey. Don't worry about it.

I'll just be able to run some checks faster while Jem's out with you."

Jem coloured a red halo around Godzilla's head, focusing his energy into the tip of his marker with a level of concentration no adult could match.

"Erainya—"

She cut me off with a look. When she spoke she addressed the top of Jem's head.

"Don't you waste time worrying about the wrong person, honey. I can tell you all about it next week when you're back at work."

I didn't answer.

Erainya muttered something in Greek that sounded like a proverb. She sighed and put her purse on her forearm.

"I'll meet you back here by nine. And no damn candy at the theatre, huh?"

Jem complained a little about that, telling her we always got Dots and Red Vines, but he knew better than to push it. He just shut his mouth and let his mother rewrite the rules as ridiculously unfair as she wanted. That's a lesson everybody learns eventually with Erainya.

23

After the movies I dropped Jem off at Erainya's house and flipped a coin, Compton or Blanceagle. I was half hoping the coin would land on its edge and I could go home.

Instead it came up Blanceagle. I headed out for the address I'd seen on Alex's driver's license, 1600 Mecca.

Mecca Street, like its namesake, is a place most people only get to once in their lifetime, only with the help of Allah, and only after many tribulations. Once you do find the road, it twists illogically through the Hollywood Park subdivision, disappearing and then reappearing, following what was once a creek bed through the rolling hills just inside Loop 1604.

I took 281 North and gave myself up to the hajj as soon as I exited, praying that someday I'd find Alex Blanceagle's house.

Hollywood Park was showing its age since I'd been there last, almost ten years before.

The pseudoranch houses that lined the streets were now more weathered, the lawns that had been grafted with fruit trees and turf grass now regressed in spots to the original scrub brush, mesquites, and cactus.

On most blocks the pristine look of affluent Gringo land had given way to more downtoearth realities– plastic daisy pinwheels in the yards, porches overflowing with tricycles, windsocks, political signboards, pumpkins, and paper skeletons.

Blanceagle's house was in one of the nicer areas, with halfacre lots and expensive castiron mailboxes and the occasional white splitrail fence. The house itself was a twostory affair, half limestone, half cedar siding, set far back from the road. I parked a block down on Mecca, then walked up the gravel driveway toward the front porch, my backpack in hand.

No exterior lights. Dim illumination from behind an upstairs curtain, more from around the side of the house—kitchen window, maybe. I was almost to the porch before I realized that the front door wasn't really painted black. It was just completely open.

I stood to one side on the porch and let my eyes adjust. Then I moved inside and stood against the wall.

A man's living room, lit only by the glow from the hallway on the right and from the staircase on the left. There were two large easy chairs and a mismatching love seat, all ugly and functional. A bigscreen TV and cabinet of stereo equipment. A bookshelf that was mostly filled with CDs stacked sideways. A bar in the corner. A slidingglass door that led out to a back porch. There was also a strange combination of smells that I didn't like at all—very old cigarette smoke, mildew, dead rat.

I listened. Faint clinking sounds came from down the hallway, from the kitchen.

I should've left right then.

Instead I walked down the hallway, into the kitchen and into the line of fire of Sam Barrera, senior regional director of ITech Security and Investigations. He was sitting behind the butcherblock table eating a gallonsized bowl of Corn Pops and his little

.22 was pointed at exactly the spot my forehead appeared as I came into the room.

There was no surprise on his face when he saw me. With his free hand he put down the spoon and wiped a dribble of milk off his chin. He said, "Drop the backpack. Come in and turn around."

"Hey, Sam. Nice to see you too."

I did what he told me, very slowly. With a guy who'd been a special agent for the FBI for sixteen years, you're better off not taking liberties. Sam came around the table and patted me down. He smelled as usual like Aramis.

He took my wallet. I could hear him rummaging through the backpack, setting things out on the counter, then sitting back down behind the table. His Corn Pops hadn't even stopped crackling.

"Look at me," he ordered.

I turned.

Sam was wearing a charcoal threepiece and a maroon tie. The gold rings made his right hand almost too chunky to hold the .22. He gave me his standard frown and hard, glassy eyes.

He held up my roll of money from Milo Chavez and showed it to me. Then my studio photograph of Les SaintPierre. Then my business card from the Erainya Manos Agency.

He waited for an explanation.

"I'm a tidge bit curious myself," I told him. "Finding a highprofile corporate dick in somebody else's kitchen, eating their Corn Pops with a spoon and a .22—I don't come across this scenario often."

"I was hungry. Mr. Blanceagle isn't going to need them."

I looked at the ceiling. The smell of dead rat was fainter in the kitchen, but still present.

When the realization finally hit me, it hit hard.

I don't know why some things knock a hole in my gut and others don't. I've seen a dozen dead bodies. I've seen two people killed right in front of me. Usually it doesn't get me until much later, in the middle of the night, in the shower. This time, even without Blanceagle in front of me, even considering I'd only met the guy once, some

thing gave way like a trapdoor under my rib cage. The idea of that poor schmuck being upstairs dead, the guy who'd looked so drunk and pathetic and outclassed at Sheckly's studio who had done me the small favour of calling me a musician to get me out the door—the idea of him being reduced to a rodent smell got to me.

Embarrassing, with Sam Barrera there. I had to swallow a couple of times, press my hands against the bumpy texture of the kitchen wall behind me.

"Upstairs?"

Barrera nodded.

"Two days ago," I guessed. "Shot with a Beretta."

Barrera started, a bit uneasy at my guesswork.

"See?" I said. "You passed up a hell of a trainee."

"I'll live with it. Go look. I'll wait."

It was almost easier than staying there in the kitchen. At least upstairs, if I threw up, I wouldn't have Barrera looking at me.

My feet were heavy on the staircase.

I breathed as shallowly as I could but it didn't help. After only two days dead in a cool house, the smell shouldn't have been this cloying. Somehow, though, every time I smelled that smell it seemed worse than the time before.

Alex was facedown on a queensized bed in the same clothes he'd worn at the Indian Paintbrush. His left limbs were extended and his right limbs curled into his body, so it looked like he was rock climbing. The sheets were in a state of disarray that conformed to his posture, a clump of fabric gathered in his right hand. Fluids had crusted his face to the bedspread. There were flies.

I stood at the doorway for a long time before I could make my feet cooperate. I forced myself to go closer, look for entrance wounds. There were two—a clean round hole in the back of the beige windbreaker, maybe shot from ten feet away, the other in Blanceagle's temple with the edges of the flesh starred and splitting, very close range.

Hard to be sure without stripping him, checking for lividity, but I was pretty sure the body hadn't been moved. He'd walked into his bedroom, somebody behind him.

They'd shot him in the back. He fell forward onto the bed. They came up and finished it off. Simple.

The rest of the room looked fuzzy, like all the light was bending toward the corpse. I tried to focus on the bedstand, the dresser, to look without touching.

There was a shoe box on the bureau top, full of correspondence that looked carefully picked through. Drawers were open. A pair of rubber gloves was draped over the top one and the chair was pushed out as if someone had just gotten up from it. Sam Barrera's work, halffinished. Maybe it was possible that even Barrera got the creeps, alone in a dark house, going through paperwork with a dead man right next to you on the bed. Maybe even Barrera had to take a Corn Pops break from that kind of work.

I didn't throw up. I somehow made it all the way back down the stairs, back into the kitchen where Barrera was still eating, one hand holding the .22 flat against the tabletop.

"Can I sit down?" I asked.

Barrera examined my face, maybe saw that I wasn't doing so hot. He waved at the stool opposite his.

I sat, took a few breaths. "I take it you haven't called the police."

Sam lifted his right ear just slightly, like God was telling him something. "Blanceagle's been dead two days. He can wait another few hours. Now I'm going to ask you what I asked Erainya: What's your business with Blanceagle? With Les SaintPierre?"

I stared at Barrera's cereal bowl, the little gold ball bearings in the white grease. My stomach did a somersault.

Barrera said, "Try some. It'll help. Corn products are good."

"No thanks. Erainya doesn't have any business with Blanceagle. I'm on my own."

"On your own," he repeated.

"That's right."

"Unlicensed."

I nodded. Sam shook his head and looked sour, like his worst assumptions about human nature had just been confirmed.

"Tell me everything," he ordered.

"And then?"

"And then we'll see."

I told him the basics. Sam asked a few questions– what did Jean look like, what exactly had Les Saint Pierre told Milo Chavez about his plan to force Tilden Sheckly's cooperation. Twice Barrera dug out handfuls of dry Corn Pops from the box and ate them, one pop at a time.

When I was done talking he said, "I've already spoken with Detective Schaeffer at SAPD. I'll talk to the Hollywood Park police. You were never here tonight. You are not working on this anymore."

"Just like that."

"Tell Mr. Chavez he'll have to do the best he can for his artists. Tell him Les SaintPierre will probably show up on his own sooner or later and there's no problem with Tilden Sheckly as far as you can determine."

"And that Santa Claus is getting him a nice tricycle for Christmas."

Barrera frowned at me. He flexed his fingers and the gold rings rubbed together with a sound like seashells.

"This thing with the singer, Miranda Daniels," he said. "This is a sideline. Forget it. You think it has anything to do with SaintPierre disappearing, you think a guy like Tilden Sheckly would waste his time with murders over a recording contract—" Barrera paused. "You don't know what you've stepped into, Navarre. I'm telling you to step back out."

"There're some shipments going through the Indian Paintbrush," I said. "Something from Germany—big heavy cylinders. Blanceagle said the arrangement has been going on for about six years. Les SaintPierre found out about it from Julie Kearnes, who probably got it from Alex Blanceagle. Les threatened to expose the business to keep Sheckly from pressing his claims on Miranda Daniels. Les miscalculated—either how bad the information was or how violently Sheck would react. Now Les has disappeared and the two people who helped him get his information are dead. How am I doing?"

"Not well," Barrera said. "Shut up."

"You spoke to Alex Blanceagle at least once before– he told me another investigator had been poking around. You were in Austin Saturday night arguing with Julie Kearnes after I knocked off surveillance. At the time she wouldn't cooperate; she shooed you out of the house with a gun. By Sunday night, after I'd rattled her too, maybe after she'd gotten some calls from Sheck's people, she was scared enough to set up a meeting with you in San Antonio. Somehow Sheck found out about it. Julie still didn't trust you so she came armed, without any information written down. She got to your rendezvous a little early or you got there a little late and she got shot in the head.

You got there, found a murder scene, and decided it was safest to drive on by and ask questions later. Who are you working for, Sam? What is Sheckly hiding that's worth killing people?"

Barrera stood up slowly, checked his gold watch. "Gather your stuff. Go home and stay there. I'm going to call it in."

"You've got five fulltime operatives just at the San Antonio office, fifteen more regionally. You've got a dozen national clients subcontracting investigations through you. If you're here in Blanceagle's living room yourself, taking trips up to Austin to argue with Julie Kearnes in person, this has to be big. Something your friends on the Bureau lined up for you, maybe."

" Your other option is that I turn you over to some of the agencies involved."

"Some of the agencies?"

"People far out of your league, Navarre. They could make very sure you stay quiet.

They would also have some hard questions for Erainya Manos about the way that you're operating. We could be looking at a revoked license for her, a guarantee your application never comes up for review. That's all before we bring in the D.A."

"You'd be such a bastard?"

Sam looked at me dispassionately. There was no implied threat. It was a simple multiplechoice test.

"All right." I started to gather up my money, my burglar's tools, my photos and paperwork. I stuffed it all into my backpack. My fingers didn't work very well. My stomach still felt fluttery, warm.

Sam Barrera watched me zip my bag. I wouldn't say he relaxed, but his eyes got a little less intense. He put his gun in his belt, behind his coat. He tilted his head sideways, stretching his neck muscles, and the little shiny black square of hair on top of his head glistened.

"You said six years," he told me. "That's about right. Maybe someday I'll show you my file cabinets, show you how a real case is put together. Maybe I can explain to you what it's like, all that buildup and documentation only to find an informant you've been courting disappeared, then another one shot in the head the day you wanted to interview him. Then to have somebody like you waltz in and act like you own the situation. You're not doing Erainya any favours following this line of work, kid. You're not doing yourself any favours. Go home."

I picked up my bag, got unsteadily to my feet.

"And Navarre—" Sam said, "you didn't find anything. Nothing to indicate Les SaintPierre's whereabouts. No documentation you can't explain."

It took me a second to realize he was actually asking me a question rather than giving me another order. I stared at him until he felt obliged to add, "SaintPierre was supposed to give me some information. It wasn't up there in Blanceagle's bedroom and it wasn't in Julie Kearnes' house."

I shook my head. The only piece I hadn't told Barrera about was the personnel files, and those weren't blackmail material. At the moment they seemed a petty thing to hide, a grudgingly small way to get some revenge on Barrera.

"Nothing," I told him. "I found nothing. Just the way you thought, Sam."

He scrutinized my face, then nodded. When I left, he was just starting to talk to the Hollywood Park police on the phone, explaining to them exactly how they were going to handle his problem.