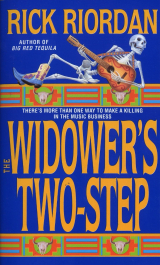

Текст книги "The Widower's Two-Step"

Автор книги: Rick Riordan

Жанры:

Разное

,сообщить о нарушении

Текущая страница: 6 (всего у книги 23 страниц)

13

When it came to snooping Jose was a pro. He remembered that the visitor had woken up Julie Kearnes at exactly elevenfifteen on Saturday night. He remembered the man going inside and arguing with Julie in her living room for eight minutes twenty seconds.

Jose had seen them through the window. He could describe the guy well—Latino, stocky, well dressed, in his late fifties. Around five feet eight, maybe 230 pounds. His car had been a BMW, goldish colour. Jose gave me the license, though after hearing the description of the visitor I was pretty sure I didn't need it.

Jose apologized that he'd only heard a few lines of their argument when the visitor came storming out of Julie's house. Something about money.

Jose said Julie Kearnes had been holding her .22 Lady smith when she came onto the porch the second time, like she was chasing the guy out.

"She didn't fire it." He sounded disappointed.

I told Jose he'd done a great service for his country and hustled him out the door. He vowed to call the number on his hand if he remembered anything else.

I went back inside Julie's house and stared at the disassembled computer. I looked at Dickhead the parrot, who'd just finished his last pistachio and was now eyeing my nose. Hungry, thirsty, alone.

"Robert Johnson wouldn't like you," I told him.

The parrot turned his head upside down and tried to look pathetic.

"Great," I said, and held out my arm.

Dickhead flew over and landed on my shoulder.

"Noisy bastard," he said in my ear.

"Sucker," I corrected.

When I got to Guadalupe Avenue, otherwise known as the Drag, the sidewalks and crosswalks were clogged with students just getting out of their afternoon classes. The fiveblock stretch of shops and cafes bordering the west side of campus boasted an impressive selection of human flotsam—greying hippies, homeless people and street merchants, musicians and soapbox preachers, sorority girls. Across the street from the chaos, the big peaceful live oaks and white limestone buildings and red tiled roofs of UT stretched out forever, like Rome or Oklahoma City, someplace that had absolutely no concept of limited space.

The Drag probably wasn't the best place in Austin to get some serious thinking done.

On the other hand, nobody was going to bother me sitting on the sidewalk outside the Student Coop with a parrot on my shoulder.

Maybe Dickhead would volunteer a few choice expressions for the passersby. Maybe if I put out a hat somebody would drop coins in it. Meanwhile I could watch time pass on the UT tower clock and think about my favourite dead woman.

Julie Kearnes' finances didn't look good. Reading through them a little closer I could see how much pressure she'd been under. She'd been getting harassing reminders from the bank that held her mortgages, from all the major credit card companies, from a local Musicians' Credit Union.

The debt negotiation she'd started might have helped, eventually, but not if she lost her biweekly pay checks from Sheck because she'd been getting too close to Saint

Pierre. Not if she lost her only paying gig with Miranda because of the Century Records deal. The temp jobs she'd been doing to fill in the cracks wouldn't have been enough to sustain her and pay the debts.

So maybe she'd decided to do some dirty work. Maybe she'd found herself getting crushed to death between Les SaintPierre and Tilden Sheckly and had to play both ends against the middle. Steal a demo tape for Sheckly or go bankrupt. Find some dirt on Sheckly for Les SaintPierre or lose your gigs.

She'd known Sheckly for years, worked in his office for most of that time, took trips to Europe with his business manager. She'd been in a position to find dirt.

Maybe what she'd dug up had been a little too good. Les had disappeared before he could play his hand. Julie had gotten nervous. She'd been pressured by some unwanted visitors over the weekend, including me. Then finally she decided to set up some kind of emergency meeting Monday morning with someone she needed help from but didn't trust. She'd taken her .22, driven to San Antonio, and walked into her own murder.

People get desperate, play in a league over their head, they often get killed. Certainly not the fault of the dashing investigator who'd only come in at the end of Act V.

Maybe. The scenario didn't comfort me any. It also didn't explain the suitcase full of Les SaintPierre's intimate apparel sitting in Julie's closet two weeks after he'd disappeared. Or the man in the gold BMW who knew enough about surveillance to spot me and outwait me at Julie Kearnes' on Saturday night.

On the street, three guys in studded leather coats and green porcupine hairdos walked by smoking clove cigarettes. A group of girls in matching wrinkled flannel, with long tangled hair and bleached white skin, stopped for a minute to ask me if I knew a guy named Eagle.

Flannel in Texas requires a real commitment. Until the cold fronts start coming in, anything except shorts and flipflops requires real commitment. I told them I was impressed. Dickhead even whistled. The girls just rolled their eyes and kept walking.

By seven o'clock the sky was turning purple. The grackles started coming in from the south again and a curve of black clouds slid in from the north, smelling like rain. The last wave of college kids flooded across Guadalupe, dispersing to seek coffee shops or frat parties.

I checked my brain for new revelations on Les Saint Pierre and Julie Kearnes, found I had none, then got up and dusted the street grime off my jeans. I went back to my VW

and locked Dickhead inside with some pistachios and a cup of water.

I walked across Guadalupe Avenue to the pay phone.

When I called my own machine, the Chico Marx voice said, "Oh, broda, you gotta plenny messages."

Carolaine Smith had called, cancelling our weekend plans because she had an outoftown special assignment. She didn't sound particularly shaken up about it.

Professor Mitchell had called from UTSA, asking me to bring a curriculum vitae and a dossier when I came to my interview on Saturday.

Erainya had called, reminding me she needed to hear by next week whether I was coming back to work and by the way could I take Jem for a few hours tomorrow night.

It would mean a lot to him. I could hear Jem in the background singing the Barney the Dinosaur song at the top of his lungs.

My next call was collect, persontoperson to Gene Schaeffer at the SAPD homicide office. Persontoperson was the most expensive calling rate I could think of. As usual Schaeffer accepted the charges graciously.

"What a privilege," he said. "I get to pay money to talk to you."

"We should form a calling circle. You, me, Ralph Arguello."

"Screw yourself, Navarre."

Ralph Arguello is one of my less reputable friends. I made the mistake of introducing Arguello to Schaeffer once, thinking they could help each other on a West Side murder case. The problems started when Ralph offered Schaeffer a finder's fee for any unclaimed goods the detective could send to Ralph's pawnshops from the SAPD

evidence locker. Schaeffer and Ralph did not come away from the encounter with a warm fuzzy feeling.

"I assume you have an excellent reason for calling," Schaeffer said.

"Julie Kearnes."

The walk light on Guadalupe changed. Students drifted across, their faces now featureless in the dusk.

"Schaeffer?"

"I remember. The fiddler. I assumed you had enough sense to get off that case."

"Just curious what you'd found."

He hesitated, probably wondering if hanging up would be enough to dissuade me.

Apparently he decided not. "We found nothing. The job was clean and professional;

only a few custodians in the SAC building that time of morning and nobody saw anything. Weapon was a highpowered rifle. Hasn't been found yet and I doubt it will be. Your client's going to have to look elsewhere for her missing demo tape."

"It's a little more than that, now."

I told Schaeffer about Les SaintPierre's disappearance. I told him about Miranda Daniels' problems getting out from under Tilden Sheckly's thumb and Milo's theory that Les might have used information from Kearnes in some kind of botched blackmail attempt. I told him about the man who had been arguing with Julie Kearnes Saturday night.

Quiet on the other end of the line. Too much of it.

"I figured you'd want to know about SaintPierre," I said. "I figured you'd want to find him, clear up some of those pesky questions, like is he still alive? Did he get Kearnes killed?"

"Sure, kid. Thanks."

"The guy in the BMW. Who does that sound like to you?"

"What do you mean?"

"Don't let's obfuscate, Schaeffer. You know damn well it's Samuel Barrera. He was at Erainya's not two hours after Kearnes got gunned down. Alex Blanceagle at the Paintbrush hinted that another investigator besides me had been poking around.

Barrera's in this somehow—not one of his twenty operatives but Barrera himself.

When was the last time Sam had a contract so juicy he handled it personally?"

"I think you're jumping to some large conclusions."

"But you'll talk to Sam."

Schaeffer hesitated. "As I remember, Barrera turned you down for a job. A couple of years ago when you were shopping around."

"What's that got to do with it?"

"What was it he told you—you weren't stable enough?"

"Disciplined. The word was disciplined."

"Really stuck in your craw, didn't it?"

"I got a trainer. I stayed with the program."

"Yeah. To prove what to who? All I'm saying, kid, you would be illadvised to go forward on this Sheckly case, to see it as some personal competition between you and Barrera. I'm advising you, as a friend, to drop it. I know for a fact Erainya isn't going to cover your butt."

I stared up at the phone lines above me. I counted rows of grackles. I said, "You called it the Sheckly case. Why?"

"Call it whatever you want."

"He's already talked to you, hasn't he? Barrera did, or some of his friends in the Bureau. What the hell is going on, Schaeffer?"

"Now you're sounding paranoid. You think I can get pressured off a case that easy?"

I thought about his choice of words. "Not easy at all. That's what scares me."

"Let it go, Tres."

I watched the lines of grackles. Every few seconds another little rag of darkness would flit in from the evening sky and join the congregation. You couldn't identify the screeching as coming from individual birds, or even from the group of birds. The sonar static was disembodied, floating noise. It echoed up and down the malls between the limestone campus buildings behind me.

"I'll think about what you said," I promised.

"If you insist on continuing, if there is anything else you need to tell me, anything that needs reporting—"

"You'll be the first to know."

Schaeffer paused. Then he laughed dryly, wearily, like a man who had lost so many coins in the same slot machine that the whole idea of bad luck was starting to be amusing. "I'm brimming with confidence about that, Navarre. I truly am."

14

Wednesday night during midterms, to hear a country band, I hadn't figured the Cactus Cafe would exactly be standing room only. I was wrong. A small whiteboard sign out front said: MIRANDA DANIELS, COVER $5. There was a line of about fifty people waiting to pay it.

Most of them were couples in their twenties– cleanlooking young urban kickers with nice haircuts and pressed denim and Tony Lama boots. A few college kids. A few older couples who looked like they'd just driven in from the ranch in Williamson County and were still trying to adjust to being around people instead of cows.

At the back of the line, two guys were having an argument. One of them was my brother Garrett.

Garrett's hard to miss with the wheelchair. It's a custom made job—white and black Holstein hidecovered seat, dingo balls along the edges, bright red wheel grips set close to the axle like Garrett likes them, nothing motorized, a Persian seat cushion designed for a guy whose weight distribution is different because he has no legs.

He's plastered the back of the chair with bumper stickers: SAVE BARTON SPRINGS, I'D

RATHER BE GROWING HEMP, several advertising Nike and Converse. Garrett enjoys endorsing athletic shoes.

The chair's got a beer cooler under the seat and a pouch for Garrett's onehitter and a bicycle flagona pole that Garrett long ago changed to a Jolly Roger. Garrett kids about putting retractable spikes on his wheels like they had in Ben Hur. At least I think he's kidding.

The guy he was arguing with had patched jeans and a black Tshirt and longish strawcoloured hair. If I'd still been in California I'd've pegged him for a surfer—he had the build and the wind burned face and the jerky random head movements of somebody who'd been watching the crests of waves too long. He was blowing cigarette smoke at the floor and shaking his head. "Naw, naw, naw."

"Come on, man," Garrett protested. "She's not Jimmy Buffet, okay? I just like the tunes. Hey, little bro, I want you to meet Cam Compton, the guitar player."

The guitar player looked up, annoyed that he had to be introduced at all. One of his brown irises had a bloody ring around it, as if somebody had tried to smash it in. He studied me for about five seconds before deciding I wasn't worth the trouble.

"You and yo' brother get your brains in the same place, son?" His accent was pure Southern, too rounded in the vowels for Texas. "What you think? She's gonna get eaten alive, isn't she?"

"Sure," I said. "Who are we talking about?"

"Son, son, son." Compton jerked his head toward the cafe door. He flicked ashes at the carpet. "Miranda Daniels, you idiot."

"Hey, Cam," Garrett said. "Calm it down. Like I told you—"

"Calm it down," Compton repeated. He took a long drag on his cigarette, gave me a smile that was not at all friendly. "Ain't I calm? Just need to teach a bitch a lesson, is all."

Several young urban kickers in line glanced back nervously.

Compton tugged on his Tshirt, stretching the blue gray markings above the breast pocket that had probably been words about six hundred Laundromats ago. He pointed two fingers at Garrett and started to say something, then changed his mind. Garrett was down a little low to be effectively argued with. You felt like you were scolding one of the Munchkins. Instead Cam turned to me and stabbed his fingers lightly into my chest. "You got any idea what Nashville's like?"

"Do you need those fingers to play guitar?"

Cam blinked, momentarily derailed. The fingers slipped off my chest. He jerked his head randomly a few times, trying to regain his bearings on the waves, then looked back at me and gave another closelipped smile. Everything under control again.

"She's gonna get one album if she's lucky, son, a week of parties, then adios"

"Adios," I repeated.

Cam nodded, waved his cigarette to underscore the point. "Old Sheck knew what he was doing, putting her with me. She ditches Cam Compton she ain't going to last a week."

"Oh," I said. Sudden revelation. "That Cam Compton. The washedup artist from Sheckly's stable. Yeah, Milo's told me about you."

I smiled politely and held out my hand to shake.

Cam's forehead slowly turned scarlet. He glanced at Garrett, then held up the lit end of his cigarette and examined it. "What'd this son of a bitch just say?"

Garrett looked back and forth between us. He pulled his scraggly saltandpepper beard, the way he does when he's worried.

"Can I talk to you?" he asked me. " 'Scuse us."

Garrett wheeled himself out of line toward the men's room. I smiled again at Cam, then followed.

"Okay," said Garrett when I joined him, "is this going to be another Texas Chilli Parlour scene?"

He gave me his evil look. With the crooked teeth and the long hair and the beard and the crazy stoned eyes, my brother can look disturbingly like a chubby Charles Manson.

I tried to sound offended. "Give me some credit."

"Shit." Garrett scratched his belly underneath the tie dyed I'm With Stupid Tshirt. He produced a joint, lit it, then started talking with it still in his mouth.

"Last time I took you out we ended up with a three hundreddollar bar tab for broken furniture. They won't let me in the Chilli Parlour for dollar magnum night anymore, okay?"

"That was different. I'd burned that guy for worker's comp fraud and he recognized me.

Not my fault."

Garrett blew smoke. "Cam Compton isn't some out ofwork schmuck, little bro. He's been on Austin City Limits, for Chris sakes."

"You know him well?"

"He knows half the people in town, man."

"Seems like an asshole to me."

"Yeah, well, you pass around good shit and give out backstage passes to major shows, you get a little leeway in the personality department, okay? You invited me here and you're buying the beer. Just don't embarrass me."

He wheeled himself around without waiting for an answer. Cam had disappeared inside the club. Probably gone to wax his guitar or tune his surfboard or something.

Garrett flashed his blue handicapped placard and made some noise and got us back to the front of the line, then inside.

The Cactus Cafe was an unlikely music venue, just a long narrow room off the corner of the Union lobby, a stage not much bigger than a kingsized bed, a little bar in back that served beer and wine and organically correct snacks. Not much in the way of atmosphere, but for fifteen years this had been one of the best places in Austin to hear small bands and solo acts. In Austin that was saying a lot.

I followed Garrett through the crowd. He drove over as many feet as he could getting past the bar and to the far wall. I had to stand next to him, pressing against the thick burgundy drapes and hoping the window didn't open and spill us all out into the rain on Guadalupe Avenue. I had enough room only if I used one foot and kept my Shiner Bock close to my chest.

"Good crowd," I said.

"I caught her last month at the Broken Spoke," Garrett said. "You wait."

I didn't have to. Just as Garrett was about to say something else applause and hoots started up behind us. The band emerged from the back room and began pressing through the crowd.

First onstage was the pudgy, whitebearded man from the photo on Milo's wall. Willis, Miranda's dad. He looked like a Texas version of Santa Claus—hair and whiskers the colour of wet cement, a jolly red face, a well fed body stuffed into Jordache jeans and a beige collar less shirt. He limped onto the stage with a cane, then substituted a standup bass for it.

Next came Cam Comptom, looking not overjoyed. He stared out at the audience grudgingly, like he was afraid they were all going to pester him for autographs. When he plugged in his Stratocaster he put a blue pick in his mouth along with several frizzy strands of his hair.

After him came a mousy librarianlooking woman who was apparently Julie Kearnes'

replacement on the fiddle. Then an elderly railthin drummer—that would be Ben French. Then a fortyish acoustic guitar player with a darkcheckered shirt and black jeans and a black Stetson that was slightly too small for his head—Brent, Miranda's older brother.

Miranda herself was not in the lineup.

Daddy Santa Claus leaned on his bass and straightened his straw hat and waved at one of the older couples in the audience. Willis might've been standing on his front porch picking for a few friends, or doing an impromptu hoedown at the local Elks Club.

The rest of the band looked stiff, nervous, like their families were being held at gunpoint in the back room.

After a few minutes of general cord fumbling and string plucking, the musicians all looked expectantly at Miranda's brother Brent.

He came up to the mike uncertainly, mumbled "Howdy," then lowered his head so you couldn't see anything except the brim of his black Stetson. Without warning he started strumming his guitar like he was afraid it might get away from him. His dad the bass player, undaunted, looked over at the others, smiled, and mouthed: "Ah one, two, three—"

The rest of the band came in and started grinding through an instrumental version of

"San Antonio Rose." . The fiddle player sawed out the melody in a watery but fairly competent fashion.

The crowd clapped, but not very enthusiastically. Many of them kept glancing toward the back of the room.

Nobody onstage looked like they were having an exceptionally good time except for Willis Daniels, who tapped his good foot and plucked his bass and smiled at the audience like he was totally deaf and this was the best damn thing he'd ever heard.

The band lurched through a few more numbers—an anaemic polka, a version of

"Faded Love" during which Cam Compton had a flashback and went into a Led Zep

pelin solo, then Brent Daniels' vocal of "Waltz Across Texas." Brent's voice wasn't bad, I decided after the second verse. None of the band members were bad, really. The drums were steady. The bass solid. Cam would've made a better rock 'n' roller but he obviously knew his scales. Even the substitute fiddler didn't miss a note. The players just didn't go together very well. They weren't much of a group. They definitely weren't worth a fivedollar cover.

The audience started to fidget. I wondered if there'd been a mistake. Maybe they'd all thought Jerry Jeff or Jimmie Dale was playing tonight. That might explain it.

Then somebody at the bar gave a good "yeehaw" as Miranda Daniels came out from the back room wearing all black denim and carrying a tiny Martin guitar. The applause and whistling increased as Miranda squeezed her way through the audience.

She looked like she did in the press release photos– petite, pale, curly black hair. She wasn't knockout beautiful by any means, but in person she had a kind of awkward, sleepy cuteness that the photos didn't convey.

The band put an abrupt stop to their waltz across Texas when Miranda got onstage.

She smiled tentatively into the lights—just a hint of her dad's crinkles around her eyes—then straightened her black shirt and plugged in her Martin.

She was definitely cute. The men in the audience would be looking at her and thinking it might not be a terrible thing to be cuddled up with Miranda Daniels under a warm quilt. That was my impartial guess, anyway.

Daddy Santa started an uptempo bass line going, tapping his foot like crazy, and the audience started clapping. Brent's rhythm guitar came in, more sure than before, then the drums. Miranda was still smiling, looking down at the floor but swaying a little to the music. She tapped her foot like her father did. Then she brushed her hair behind her ear with one hand, took the microphone, and sang: "You'd better look out, honey—"

The voice was amazing. It was clear and sexy and overpowering, not a hint of reservation. But it wasn't just the voice that nailed me to the wall for the next thirty minutes. Miranda Daniels became a different person– nothing tentative, nothing awkward. She forgot she was in front of an audience and sang every emotion in the world into the microphone. She broke her heart and fell in love and snared a man and then told him he was a fool in one song after another, hardly ever opening her eyes, and the lyrics were typical country and western cornball but coming from her it didn't matter.

Toward the end of the set the band dropped away and Miranda did some acoustical solos, just her and her Martin. The first was a ballad called "Billy's Senorita," about the Kid from his Mexican lover's perspective. She told us what it was like to love a violent man and she made us believe she'd been there. The next song was even sadder—"The Widower's TwoStep," about a man's last dance with his wife, with references to a little boy. It was unclear in the lyrics how the woman died, or whether the boy died too, but the impact was the same no matter how you interpreted it.

Nobody in the cafe moved. The other band members could've packed up and left for the night and nobody would've noticed at that point. Most of the band looked like they knew it, too.

I glanced over at Cam Compton, who had come to sit next to Garrett in a chair some woman had gladly given up for him. As Cam listened to Miranda his expression slipped from amused disdain into something worse– something between resentment and physical need. He looked at Miranda the way a hungry vegetarian might look at a Tbone. If it was possible to like him less, I liked him less.

At the break the musicians dissipated into the audience. Miranda escaped into the back room. I was trying to figure out the best way to get in to talk to her when Cam Compton made up my mind for me. He downed what must have been the fourth beer someone had bought for him, got up unsteadily, and told Garrett, "Time I had a talk with that girl."

"Wait a minute," I said.

Cam pushed me into the curtains. I didn't have room or time to do anything about it.

When I got to my feet again Garrett said, "Uhuh, little bro. Cool it, now." Then he saw my eyes and said, "Shit."

Cam was moving toward the back room like a man with a purpose. A woman got in Cam's way to tell him how great he was and he pushed her into somebody at the bar.

I followed Cam like I was a man with a purpose too. I was going to beat the living crap out of him.